A ‘can do’ attitude – ‘apply yourself and you will succeed’

Birmingham was the epitome of the great city brought low by post-war planning that gave the car and shopping centres ascendancy. The good news is that in the last decade it has managed to reverse many of the worst elements and a new, more walkable city is emerging from the rubble.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 11.7kms (7.3 miles)

- Typical time: 3 hrs

- Height gain: 30 metres

- Start & finish: Birmingham New Street Station (B5 4AH)

- Terrain: Straightforward; sturdy footwear recommended

BEST FOR

| ‘Green Spaces’ | |

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Brindleyplace, City Centre Gardens, Warstone Lane Cemetery, Key Hill Cemetery, Eastside City Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | The canals (‘more canals than Venice’!) |

| Stunning cityscape | Champagne Bar at Marco Pierre White at the top of the Cube (25th floor); Skyline Viewpoint in Birmingham Library, Bureau Bar |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Georgian (1714-1836) | St Philip’s Cathedral (1715), St Paul’s (1779) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Synagogue (1856), Old Town Hall (1874), 122-124 Colmore Row (1900), City Art Gallery, School of Art (1885), Bell Eddison Telephone Exchange (1896) |

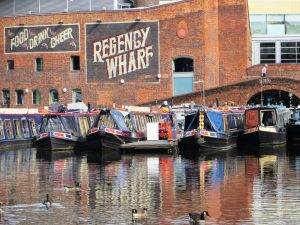

| Industrial Heritage | Gas St Basin (1790s), The Jewellery Quarter, Curzon St Station (1838) |

| Modern (post-1918) | Birmingham Station (2016), The Rotundam (1965), The Selfridges Building (2003), The Cube (2010), Brindleyplace (1990s), The Library (2013) |

| ‘Fun stuff’ | |

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Café Opus, The Bureau Bar, Java Lounge Coffee House, Vee’s Deli, Peel & Stone |

| Quirky Shopping | The Jewellery Quarter, Great Western Arcade |

| Places to visit | Ikon Contemporary Art, City Art Gallery, The Pen Museum, Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, Think Tank (Science Museum) |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Birmingham Pride (late May), Birmingham International Carnival (August 2019-biennial), St Patrick’s Day City Centre Parade ( March), Frankfurt Christmas Market (Dec) |

City population: 1,092,330 (2013 mid-year estimate)

Urban population: 2,440,986 (2013 mid-year estimate)

Ranking: 2nd largest city in the UK

Date of origin: Anglo-Saxon era, 6th or early 7th century

City status: granted in 1889. It was the first conurbation without a cathedral to be given city status; St Philip’s was nominated as its cathedral in 1905

‘Type’ of city: A city of the industrial revolution; but driven by workshops, not large factories

Some famous inhabitants: Matthew Boulton (industrialist), Edward Burne-Jones (Pre-Raphaelite painter), Joseph Chamberlain (politician), Tony Hancock (comedian), Enoch Powell (politician), Malala Yousafzai (Pakistani activist), James Watt (inventor), Alec Issigonis (designer of the Mini); Ozzy Osbourne (member of Black Sabbath, founder of heavy metal)

Notable city architects/planners: Sir Herbert Manzoni (City Engineer 1935-1963), John Madin (1924-2012)

Number of listed buildings: 1,516, of which 23 are Grade I and 108 Grade II*

Films/TV series shot here: Brassed Off (1996-Town Hall), She Who Brings Gifts (2015), Take Me High (1973 – Gas St Basin), Line of Duty (TV series)

Famous quotes about Birmingham:

“I grew up in Birmingham, where they made useful things and made them well.” (Lee Child, author of the Jack Reacher novels)

“It is an honour for me to be here in Birmingham, the beating heart of England.” Malala Yousafzai (Pakistani activist)

Estimated % of green space in the city (Eski): 25% (4th out of Top 10 cities)

CONTEXT

Birmingham has been around for over a millennium but still has that strange feeling of being a work in progress. By size and historical importance it is the country’s second city, and yet it feels less formed and certain of itself than many other big cities. The ‘new layout’ of the city still feels like just that – a layout, a concept on a drawing board called the ‘Big City Plan’, fuelled by ‘starchitecture’, sculptures and the requisite division of a city into ‘quarters’ (of which there always seem to be more than four!) Being at the centre of the country, without obvious topographical ‘stand out’, for many people it’s the city that one goes past rather than chooses as a destination in itself.

There can’t be many major cities without a significant river running through them or a seafront. There are no navigable rivers: the Rea, on which the City was founded, is little more than a culverted stream; and the Tame, which only passes through the northern suburbs, is not navigable. The River Cole, which runs through the south-east of the city through to the north-west, is too shallow for anything bigger than a raft. So Birmingham had to bring the water to it, in the linear form of the canals, which gave it access to the outside world and ultimately enabled it to become one of the first great global export centres of the world.

Birmingham’s early history is that of a remote and marginal area. The main centres of population, power and wealth in the pre-industrial English Midlands lay in the fertile and accessible river valleys of the Trent, the Severn and the Avon. The area of modern Birmingham lay in between, on the upland Birmingham Plateau and within the densely wooded and sparsely populated Forest of Arden. A medium-sized market town during the medieval period, it only began to gain commercial significance in the 16th century with the manufacture of iron goods.

It was not until the 18th century that Birmingham grew to international prominence, at the heart of the Midlands Enlightenment and subsequent Industrial Revolution. The town established itself at the forefront of worldwide advances in science, technology and economic development, producing a series of innovations that laid many of the foundations of modern industrial society. By 1791 it was being hailed as ‘the first manufacturing town in the world’. Birmingham had a highly distinctive economic profile, with thousands of small workshops practising a wide variety of specialised and highly skilled trades, encouraging exceptional levels of creativity and innovation.

Amongst the many inventions made in Birmingham, the most notable of all was the development of the industrial steam engine by James Watt and Matthew Boulton in 1776. Freeing for the first time the manufacturing capacity of human society from the limited availability of hand, water and animal power, this was arguably the pivotal moment of the entire industrial revolution.

The resulting high level of social mobility also fostered a culture of broad-based political radicalism, that under leaders from Thomas Attwood to Joseph Chamberlain was to give the town a political influence unparalleled in Britain outside London, and a pivotal role in the development of British democracy.

Birmingham rose to national political prominence in the campaign for political reform in the early 19th century, with Thomas Attwood and the Birmingham Political Union bringing the country to the brink of civil war during the ‘Days of May’ that preceded the passing of the Great Reform Act in 1832. The Union’s meetings on Newhall Hill (we will pass this spot) in 1831 and 1832 were the largest political assemblies Britain had ever seen. Lord Durham, who drafted the Act, wrote that “the country owed Reform to Birmingham, and its salvation from revolution”.

Birmingham was heavily bombed in the Second World War, being a major centre of munitions factories. It was the third hardest hit city in the UK, after London and Liverpool. Damage to buildings and infrastructure was very substantial, necessitating and enabling much re-development after the war.

This process of rebuilding was led by the very pragmatic Sir Herbert Manzoni, who held the role of City Engineer and Surveyor of Birmingham from 1935 until 1963. This position put him in charge of all municipal works and his influence on the city completely changed the shape of Birmingham. His priorities after the war were re-housing (both as a result of homes destroyed in the Blitz and slum clearance), civic redevelopment and sorting out traffic congestion, the top priorities for almost all UK cities in that period.

Manzoni encouraged zoning of areas and redevelopment and did not believe in the preservation of old buildings. In his words:

“I have never been very certain as to the value of tangible links with the past. They are often more sentimental than valuable… As to Birmingham’s buildings, there is little of real worth in our architecture. Its replacement should be an improvement… As for future generations, I think they will be better occupied in applying their thoughts and energies to forging ahead, rather than looking backward.”

The inner ring road, which came to be known as the ‘concrete collar’, is perhaps his most damning legacy in terms of surrendering the city space to the great god of the motor car and making it deeply inhospitable to the pedestrian. But on the order charge is also the loss of dozens of fine Victorian buildings like the intricate glass-roofed Birmingham New Street Station, the original Bull Ring Market Halls and the old Central Library, which were all destroyed in the 1950s and 1960s.

These planning decisions were to have a profound effect on the image of Birmingham in subsequent decades, with the mix of concrete ring roads, shopping centres and tower blocks giving Birmingham its ‘concrete jungle’ tag. One commentator described Manzoni’s vision of Birmingham as a “Godless, concrete urban hell“, another a “brutalist, concrete-dominated slave to the motor car“.

Birmingham was also often described as being ‘Britain’s motor city’. And this wasn’t just because it was the headquarters of the UK car industry. A complete car culture took hold, along American lines. It held many dubious auto firsts: the first city to have a dual carriageway thrust into its heart; the first to authorise one-way streets; the first to have ‘integrated motor houses’ i.e. garages. The elevated roadways, most famously ‘Spaghetti Junction’ which we all talked about in awed tones in our childhood, unsure as to whether an analogy with our favourite ‘modern’ food was a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ thing, created this sense of the complete ascendancy of the car.

But all bad things come to an end eventually (OK, maybe not the Westway in London), and during the 1980s the council and its planners started to come to a realisation that all was not well; and they set out to improve the ‘liveability’ of the city. Since then massive projects have taken place to make the city more appealing and ‘connected’ once again. This regeneration has been driven by the ‘Big City Plan’, and its most notable successes include the total re-building of the Bullring area, the regeneration of the canals and a new library. The city that you walk through today is quite different from the city of a generation ago, and much more walker friendly. And most remarkably of all, even some sections of the inner ring road have been got rid of.

The Birmingham Development Plan states: “By 2031 Birmingham will be renowned as an enterprising, innovative and green city that has undergone transformational change growing its economy and strengthening its position on the international stage.” Hurrah! Because it’s a plan that is actually being put into practice.

THE WALK

From the moment we alighted the train, surrounded by a stunning new station full of light and space, we appreciated that Birmingham has been transformed in little more than a generation. So very different from the grim 1960s warren of the old New Street, deserved winner of the ugliest building in Britain award back in the day.

And the landmark Rotunda (1965), which we shortly see on our left, is a triumph of 1960s architecture brushed up for the 21st century. Listed Grade II, it has recently had the ‘Urban Splash’ treatment, being converted from an office block to luxury apartments. In their words, “we wanted the Rotunda to set a new standard for city centre living.” And it’s a bit of a rarity in Birmingham, a building that has been re-purposed rather than knocked down and starting things again.

And when we reached the Bullring, we realised that things are really not the same at all – where I recall only a decade ago there had been acres of concrete, impersonality and dull chains, now there are delightful walking spaces, punctuated by trees, statues, steps, water features; and then suddenly, to your left, the visual raucousness of the Selfridges ‘bubble wrap’ building (2003). The facade comprises 15,000 anodised aluminium discs mounted on a blue background. One architectural critic described this effect rather harshly as “blue blancmange with chicken pox….scaleless, uninviting.” As a walker, though, I think it works – it is an extremely useful city ‘trig point’. And since its construction, the building has become an iconic architectural landmark and ‘poster building’ that represents the regeneration of Birmingham.

Apparently, the technical term for this type of architecture is ‘Blobitecture’ – a movement in architecture in which buildings have an organic, amoeba-shaped, building form. The architecture firm Future Systems was appointed by Selfridges’s then chief executive, Vittorio Radice (another Italian with designs on Birmingham…) to construct the store. He wanted a distinct design approach that would set the store apart from the rest of the development and become an instantly recognisable signpost for the brand. Future Systems’ design was intended to evoke the female silhouette and a famous chain mail dress designed by

Apparently, the technical term for this type of architecture is ‘Blobitecture’ – a movement in architecture in which buildings have an organic, amoeba-shaped, building form. The architecture firm Future Systems was appointed by Selfridges’s then chief executive, Vittorio Radice (another Italian with designs on Birmingham…) to construct the store. He wanted a distinct design approach that would set the store apart from the rest of the development and become an instantly recognisable signpost for the brand. Future Systems’ design was intended to evoke the female silhouette and a famous chain mail dress designed by  Paco Rabanne in the 1960s.

Paco Rabanne in the 1960s.

As we sat down for coffee before starting the walk proper, looking across at the ‘blobs’, we watched the people walking up the steps – al sorts, going about their work or leisure, but all apparently unrushed and very content with the ‘walking space’ – at last Birmingham is creating spaces that are working for people.

One thing that doesn’t seem to bother Brummie planners too much anymore, and for which I admire them, is old and new standing cheek by jowl – in the background a futuristic building, but in the foreground an 1830s statue of Admiral Lord Nelson (honoured for keeping the sea lanes open, a vital part of Birmingham’s export success), and down the slope a Victorian Gothic church. From Nelson’s vantage point you are looking down into the River Rea Valley, but there’s no visual clue apart from the slope as the river is culverted for this stretch.

Walking past St Martin’s Church brought us to the bustling market area. There have been markets in this area since the Middle Ages, and the enthusiasm of the traders more than compensates for the rather insalubrious surroundings. If they are open when you are visiting (Mon-Sat, 9am-5.30pm), try and walk through them; first up is the open market, with a fabulous range of fruit and veg; next, go into the building to the west of the open market, called St Martin’s Market: it has around 350 stalls, specialising in fabrics, fashions and collectables. Then the Indoor Market, which has 140 stalls, including the famous fish market, meat and game. The sheer range is impressive, including halal meats and fish for the Chinese market. Warning: this market, once seen, is likely to cause intense envy, in the (almost inevitable) event that you don’t have such a fine market where you live!

Across the road is the rather unprepossessing Arcadian Plaza, the centre of Birmingham’s Chinatown. In 1950 the Chinese population was just 200; it was in the 1960s that men came here from Hong Kong and The New Territories. Many of them set up catering businesses and, as the Chinese takeaway grew in popularity, so more Chinese came and brought their families with them. A cluster of Chinese businesses developed around Hurst Street and by the 1980s this area was officially recognised as the Chinese Quarter. Now the Chinese population is estimated to be around 12,000.

The theme is continued with the Chinese pagoda in the centre of Holloway Circus. Wing Yip gave this pagoda to Birmingham as a gesture of thanks to the city for providing him with a home. He had arrived by boat from Hong Kong in 1959 at the age of 19 with just £10 in his pocket. He opened a grocery store in Birmingham and, from these small beginnings, built a food empire that now supplies more than 2,000 Chinese restaurants around the country. Brummies, whether born and bred or incomers, seem to share a strong worth ethic.

But it’s really very hard to appreciate the craftsmanship and beauty of this pagoda, as we found ourselves marooned on a traffic island with cars roaring past on either side. A powerful reminder of those bad old 70s when ring roads were like a noose around a city’s neck, throttling the life out of the centre. And how will we get across? By a subway, and this subway offers all that is truly bad about subways – litter, the smell of urine, broken tiles and puddles. The only thing that kept our pecker up is that we could now glimpse the modernist ‘Cube’ on the far side, fifty years fast forward into a much-improved landscape.

On our way, we passed the ‘Singers Hill’ Synagogue which dates from 1856 and has played an important part in the lives of the Jewish community in Birmingham. There has been a small Jewish community in Birmingham since the thirteenth century and there was an earlier synagogue here in the eighteenth century. The one you see today was designed by H. Yeoville Thomason, an eminent Birmingham architect who was also responsible for The Council House and The City Art Gallery; and most of its original features are still intact today, including 26 stained glass windows.

The Mailbox is a good example of the building and rebuilding that has taken place in Birmingham over the centuries. When it opened in 1970 as the Royal Mail sorting office, it was the largest mechanised sorting office in the country. Canalside wharves were demolished to make way for it and a tunnel connected it to New Street Station. The building re-opened in 2000 as an upmarket development of offices, shops and restaurants. The BBC moved here in 2004 from their previous studios at Pebble Mill. You can tour the studios and there is a large public space where you can see live broadcasting taking place.

The 25-storey Cube (2010), which we came to next (left in the photo above), was designed by Birmingham-born Ken Shuttleworth, who designed London’s Gherkin building with Norman Foster. He describes his creative process: “The cladding for me tries to reflect the heavy industries of Birmingham which I remember as a kid, the metal plate works and the car plants – and the inside is very crystalline, all glass; that to me is like the jewellery side of Birmingham, the light bulbs and delicate stuff – it tries to reflect the essence of Birmingham in the building itself.” Since the building opened it has tended to divide opinion. Jones the Planner, a man who always holds a strong view, says of it: “This is a typically glitzy show-off building with one side of the cube a gigantic open fretwork at upper levels – made with Adobe Illustrator’s vacuous building tool.” You decide.

The 25-storey Cube (2010), which we came to next (left in the photo above), was designed by Birmingham-born Ken Shuttleworth, who designed London’s Gherkin building with Norman Foster. He describes his creative process: “The cladding for me tries to reflect the heavy industries of Birmingham which I remember as a kid, the metal plate works and the car plants – and the inside is very crystalline, all glass; that to me is like the jewellery side of Birmingham, the light bulbs and delicate stuff – it tries to reflect the essence of Birmingham in the building itself.” Since the building opened it has tended to divide opinion. Jones the Planner, a man who always holds a strong view, says of it: “This is a typically glitzy show-off building with one side of the cube a gigantic open fretwork at upper levels – made with Adobe Illustrator’s vacuous building tool.” You decide.

And now we reach the part of the canal where the vast majority of people who walk alongside the water are to be found, along the half mile or so around Gas St Basin, the epicentre of the network; now all beautifully restored, still carrying narrow boats and replete with restaurants and bars every way you look.

No guide to Birmingham would be complete without mentioning the canals. As the Industrial Revolution took off in the 1760s, Birmingham was a modest town of about 35,000 people. It was only developing slowly as a manufacturing centre as, being in the centre of England, it was hindered by not having a port or even a river with access to the sea. Roads were poor and goods had to be transported by waggon or packhorse.

No guide to Birmingham would be complete without mentioning the canals. As the Industrial Revolution took off in the 1760s, Birmingham was a modest town of about 35,000 people. It was only developing slowly as a manufacturing centre as, being in the centre of England, it was hindered by not having a port or even a river with access to the sea. Roads were poor and goods had to be transported by waggon or packhorse.

Birmingham’s business people quickly recognised that canals could help overcome this fundamental constraint to growth. Within 40 years Birmingham found itself at the hub of the country’s canal networks. The canals made it possible to transport raw materials like coal cheaply, and this ignited Birmingham’s growth as a manufacturing centre. Raw materials were transported on the canal right up until the 1960s.

When you tell people you are off to Birmingham for a city walk, the reactions are almost the same from everyone: “Ah, it’s improved quite a lot recently so I hear… and did you know, Birmingham is said to have more miles of canal than Venice?” And notice the slightly hesitant phrasing, ‘said to have’ rather than the more confident ‘has’. Being a logical sort of chap I wanted to check that out; and, of course, the internet has lots on the subject.

Fact 1: At its working peak, the Birmingham canal network contained about 160 miles of canals; today just over 100 miles are navigable. There are 35 miles of canals within the city boundaries.

Fact 2: According to Wikipedia, Venice has 26 miles of canal

Fact 3: Birmingham has six canals; or 11 if you’re being generous (adding in branches etc.) By contrast, Venice has 177 canals.

Fact 4: Birmingham City covers an area of 268Km², whilst the Historic Centre of Venice covers 8Km². So per sqr km, Venice has 25 times greater density of canals.

In the words of one slightly disgruntled local blogger: “Whilst in a technical sense – that of how many miles of canal there is in Birmingham compared to Venice – the factoid is true, it’s also true that Birmingham has more Brummies than Venice, more roads than Venice, more streetlamps than Venice, and more former Spitfire factories than Venice.”

Ok, debate over, calm down, keep walking along the canal, until you are just past the Seal Life centre on your left (designed by Sir Norman Foster, and probably the furthest from the sea sea-life centre anywhere in the country) and the National Indoor Arena ahead. We cut back left (south) down Arena Walk to the entrance to Sea Life, then right into  Brindleyplace’s central square, an agreeable open-space with well-tended lawns and trees. Named after the 18th-century canal engineer, James Brindley, this district used to be a warren of factories but had lain derelict for many years. If you’re not into post-modern architecture (the overall master plan was laid out by Terry Farrell), you probably won’t warm to these buildings – they seem to lack a sense of time and place – but at least in terms of walkability, dwell time and community space the development is definitely a success.

Brindleyplace’s central square, an agreeable open-space with well-tended lawns and trees. Named after the 18th-century canal engineer, James Brindley, this district used to be a warren of factories but had lain derelict for many years. If you’re not into post-modern architecture (the overall master plan was laid out by Terry Farrell), you probably won’t warm to these buildings – they seem to lack a sense of time and place – but at least in terms of walkability, dwell time and community space the development is definitely a success.

Next, we swept over the canal footbridge, through the rather disjointed ICC building and out into the impressive Centenary Square, re-named in 1989 to commemorate the centenary of Birmingham achieving city status. The area had been an industrial area of small workshops and canal wharves before it was purchased by the council in the 1920s for the creation of a grand civic centre scheme to include museums, council offices, cathedral and opera house. In 1918, William Haywood published the book The Development of Birmingham within which he proposed a scheme to create a grand civic centre west of Victoria Square. (Cities have always been subject to grand plans, seldom more than partially implemented – this one was no exception!)

Next up is the new Birmingham Library (2013). It is viewed by the Birmingham City Council as a flagship project for the city’s redevelopment. The strange thing is, it’s the third library since the War, and the previous two (in very different styles – Victorian Gothic and Brutalist) both had their great admirers. What’s this obsession with building new libraries? Probably in search of that oldest of status symbols – knowledge.

The latest library incarnation was designed by architect Francine Houben, founder and director of Dutch architecture practice Mecanoo. In a similar way to the Cube, the exterior’s interlacing rings are intended to reflect the city’s canals and tunnels. “We see the circle as a motif of the city,” Houben explains. “The facade recalls the industrial gasometers as well as the history of the jewellery trade here.” She described the building as a ‘people’s palace’.

There’s just one problem if you want to visit, though. Thanks to local government cuts, the ‘people’s palace’ doesn’t open until 11, it closes at 5 and it’s closed on Sundays. By my calculations, it’s open 40 hours a week, population 1.1 million; compare that to my hometown Stamford, population 21,000, where the library is open 48 hours a week – bizarre! If it’s open, you’ll almost certainly find what you’re looking for. Just thought I’d warn you! It’s odd that they can’t make more use of this stunning building in its incredibly central location, especially when you think how much it cost to build – a staggering £189 Mn!

The best bit for us walkers is that you can do a ‘vertical walk’ through the library, ably assisted by a scintillating array of escalators that whisk you from one floor to the next whilst giving you a great vantage point of each floor. Start in the rotunda on the ground floor which gives you a stunning view up through the library. Take the escalators to the Knowledge Floor (Level 2), then the Discovery Floor (Level 3), where you will find a delightful outdoor garden; then up to the Archives, Heritage & Photography Floor (Level 4). Then switch to the lift to get you to the 7th floor, where you will find the Secret Garden, with quiet places to sit high above the bustle of the city; then take the blue lift up to the Shakespeare Memorial Room on Level 9, which houses one of the most important Shakespeare collections in the world, including a copy of the First Folio 1623. Then finally head to the Skyline Viewpoint for panoramic views across the city, towards the many hills that surround Birmingham. For a virtual tour, watch ‘Fly through Library of Birmingham’.

Across the way on the other side of Broad St stands the statue of Boulton, Watt and Murdoch, also nicknamed ‘The Golden Boys’ or ‘The Carpet Salesmen’, depicted discussing engine plans. The three men were pioneers of the industrial revolution in late 18th century England. James Watt’s improvements to the steam engine and William Murdoch’s invention of gas lighting made them famous throughout the world. Matthew Boulton, entrepreneur and industrialist, harnessed their talents in a company that made everything from tableware and copper coinage to steam engines. His home, Soho House, is now a museum.

It is a poor location for a statue; it was originally planned to be part of a much more cohesively planned civic square, but that never materialised; plans are now afoot to relocate it into the main square itself, or with its obvious railway links, across to Eastside and the HS2 terminus.

And then perhaps time to relax for a bit in the City Centre Gardens, hidden away behind the library; lovely well-planted old-fashioned gardens; items to be little known and visited, but it a lovely, well-tended green spot.

Then it’s time to go through Paradise as it’s now called, but was previously the circus of hell (aka Paradise Circus). Until 1989, the route across the inner ring road was via a dingy underground subway. Then, as part of the Centenary Square redevelopment, Centenary Way was constructed, taking walkers over the ring road. And now a much more ambitious £500 million + regeneration scheme is underway here, to include offices and other buildings; the (happy) outcome for walkers will be a much wider, tree-lined boulevard (how they love to use the French word to signify ample width, greenness and the ‘good life’) that links Centenary Square to Chamberlain Square. How the long journey (circa half a century) back to walkability is epitomised by one road crossing.

Chamberlain Square contains several notable buildings and a memorial to Joseph Chamberlain in gratitude for his services to the City. He was a Birmingham businessman as well as Mayor of the city and a Member of Parliament in the latter part of the nineteenth century. We come across his legacy again later in the walk.

To our right is the back of the Town Hall and across the Square is the Museum and Art Gallery, with its clock tower nicknamed ‘Big Brum’. We can see a bridge linking this to another building which resembles the Bridge of Sighs in Venice.

The first of the monumental town halls that would come to characterise the cities of Victorian England, Birmingham Town Hall, opened in 1834; it was also the first significant work of the 19th century revival of Roman architecture, a style chosen here in the context of the highly charged radicalism of 1830s Birmingham with its republican associations. The design was based on the proportions of the Temple of Castor and Pollux in the Roman Forum. “Perfect and aloof” on a tall, rusticated podium, it marked an entirely new concept in English architecture.

The first of the monumental town halls that would come to characterise the cities of Victorian England, Birmingham Town Hall, opened in 1834; it was also the first significant work of the 19th century revival of Roman architecture, a style chosen here in the context of the highly charged radicalism of 1830s Birmingham with its republican associations. The design was based on the proportions of the Temple of Castor and Pollux in the Roman Forum. “Perfect and aloof” on a tall, rusticated podium, it marked an entirely new concept in English architecture.

There are also two sculptures in Victoria Square – Dhruva Mistry’s ‘floozie in the jacuzzi’ as it has become known (officially called ‘The River’), recently bedevilled by leakage problems; and an Anthony Gormley statue entitled Iron:Man. Thes two sculptures rather add to the impression of a city trying very hard, but somehow the overall effect is rather disjointed. In Jonathan Mead’s opinion: “Birmingham is trying to overcome its featurelessness with tokenist works of symbolic intent.” Still, much better than how it was at the end of the 80s, a traffic bottleneck.

There are also two sculptures in Victoria Square – Dhruva Mistry’s ‘floozie in the jacuzzi’ as it has become known (officially called ‘The River’), recently bedevilled by leakage problems; and an Anthony Gormley statue entitled Iron:Man. Thes two sculptures rather add to the impression of a city trying very hard, but somehow the overall effect is rather disjointed. In Jonathan Mead’s opinion: “Birmingham is trying to overcome its featurelessness with tokenist works of symbolic intent.” Still, much better than how it was at the end of the 80s, a traffic bottleneck.

Walking along New Street and then up Bennett’s Hill, we saw on our left a blue plaque at No. 11, commemorating Edward Burne-Jones, closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, was born here.

Soon we came upon The Cathedral Church of Saint Philip (1715) and its churchyard, a swathe of green in the middle of the city. Built as a parish church, St Philip’s became the cathedral of the newly formed Diocese of Birmingham in 1905. It’s the third smallest cathedral in England after Derby and Chelmsford and, in Alexandra Wedgwood’s words, is “a most subtle example of the elusive English Baroque”.

Soon we came upon The Cathedral Church of Saint Philip (1715) and its churchyard, a swathe of green in the middle of the city. Built as a parish church, St Philip’s became the cathedral of the newly formed Diocese of Birmingham in 1905. It’s the third smallest cathedral in England after Derby and Chelmsford and, in Alexandra Wedgwood’s words, is “a most subtle example of the elusive English Baroque”.

In 1884 the church was enlarged by Birmingham architect J A Chatwin in anticipation of its becoming a cathedral. At this time four stained glass windows were designed by Edward Burne-Jones and made by Morris & Company and installed in the chancel and at the west end.

A building of particular note as you walk along the handsome Colmore Row is Hudson’s Coffee House (1900) at 122-124, listed Grade I, designed in the Arts and Crafts style (left picture below). Pevsner describes it as “one of the most original buildings of its date in England” – and I agree! Nowadays it is home to the highly-rated Java Lounge Coffee House, owned by Akram Almulad, a Brummie born to Yemeni parents. His mission has been to bring great coffee to the city and, according to him “Yemen is where the earliest substantiated evidence of either coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee tree appears in the middle of the 15th Century”.

There are also several good buildings in upper Newhall Street, including the former Bell Edison Telephone Exchange (1896) on the corner of Edmund Street on the right, at No. 19. This gorgeous terracotta building (right picture above) by the local architect Frederick Martin is Grade I listed. The building apart, note the beautifully decorated metal gates in the archway.

Next, we need to take a little detour down Edmund St towards the ‘Bridge of Sighs’ to reach my favourite Victorian Birmingham building of them all, the Birmingham School of Art (1885), the first Municipal School of Art and the leading centre for the Arts and Crafts Movement.

Next, we need to take a little detour down Edmund St towards the ‘Bridge of Sighs’ to reach my favourite Victorian Birmingham building of them all, the Birmingham School of Art (1885), the first Municipal School of Art and the leading centre for the Arts and Crafts Movement.

The School is a red-brick Victorian Gothic structure, completed after its architect J. H. Chamberlain’s death by his partner William Martin and his son Frederick Martin, and widely considered as Chamberlain’s masterpiece. Its Venetian style and naturalistic decoration are much influenced by John Ruskin’s Stones of Venice.

The Arts & Crafts Movement was closely linked to Birmingham. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed by a group of friends at the University of Oxford, including William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and some of Burne-Jones’ associates from Birmingham at Pembroke College, who became known as the Birmingham Set. They had first-hand experience of modern industrial society and combined their love of the Romantic literature of Tennyson, Keats and Shelley with a commitment to social reform.

Morris and Burne-Jones had originally intended to join the priesthood, but in 1855, returning to Burne-Jones’ house in Bennett’s Hill after touring the cathedrals of Northern France, they decided instead to pursue careers in the visual arts, Burne-Jones resolving to become a painter and Morris an architect. The following day they discovered a copy of Malory’s ‘Morte d’Arthur’ in a Birmingham bookshop, which was to be one of their great inspirational works.

Arts and Crafts practitioners in Britain were critical of the government system of art education which was based on design in the abstract with little teaching of practical craft. This lack of craft training also caused concern in industrial and official circles, and in 1884 a Royal Commission (accepting the advice of William Morris) recommended that art education should pay more attention to the suitability of design to the material in which it was to be executed. The first school to make this change was the Birmingham School of Arts and Crafts, which led the way in working with the material for which the design was intended rather than designing on paper. This tradition has carried through to the current day. Unlike many other British art schools, Birmingham specialises in all the applied arts and has become particularly renowned for its teaching of metalwork, jewellery, enamels, design and book illustration.

Once we had traversed the ‘concrete collar’ of the ring road for the third time on this journey, we reached the impressive Jewellery Quarter, a part of the Birmingham experience definitely not to be missed and having some of the same qualities as Clerkenwell in London, with its unpretentious warehouses and factories. The first big clue that you have reached the quarter is the Birmingham Assay Office, on the corner of Newhall St and Charlotte St, with blue metal railings. Set up in 1773, all silverware had up to then been sent either to London or Chester to be hallmarked. The Quarter came to make a large proportion of the British Empire’s fine jewellery.

Birmingham’s Assay Office is still the busiest in the world today, hallmarking around 12 million items a year. The Jewellery Quarter has Europe’s largest concentration of businesses involved in the jewellery trade and produces around half of all the jewellery made in the UK, employing over 6,000 skilled craftsmen, each workshop typically small-scale, employing between five and fifty people. In other words, Birmingham still doing what it has always done so well, making things in workshops.

The Birmingham & Fazeley Canal, a short stretch of which we took at this point, plunges down here through dramatically floodlit archways, office undercrofts and narrow tunnels. It is an atmospheric link to the past in the middle of a modern city.

In its industrial heydey, this Farmer’s Bridge Flight was a hectic place, kept open day and night, and lit by gas during the hours of darkness. There was said to be nearly 70 steam engines and about 124 wharfs and works along the banks of the canal between Farmer’s Bridge and Aston.

St Paul’s Square, which we reached next, was created in the late 1770s on the Newhall estate of the Colmore family. It was an elegant and desirable location in the mid 19th century, but by the end of the century had been largely taken over by workshops and factories, with the fronts of some buildings being pulled down to make shop fronts or factory entrances. Much restoration was done in the 1970s and many of the buildings are now Grade II listed. The well-proportioned St Paul’s Church (1779) was the church of Birmingham’s early manufacturers and merchants – the engineers Matthew Boulton and James Watt had their own pews here.

St Paul’s Square, which we reached next, was created in the late 1770s on the Newhall estate of the Colmore family. It was an elegant and desirable location in the mid 19th century, but by the end of the century had been largely taken over by workshops and factories, with the fronts of some buildings being pulled down to make shop fronts or factory entrances. Much restoration was done in the 1970s and many of the buildings are now Grade II listed. The well-proportioned St Paul’s Church (1779) was the church of Birmingham’s early manufacturers and merchants – the engineers Matthew Boulton and James Watt had their own pews here.

Next, we sought out what could easily lay claim to being the world’s most historic sandpit in nearby Newhall Hill! On 7 May 1831 the Gathering of the Unions was held here. This was a giant demonstration involving 200,000 people and 40 Unions, orchestrated by the Birmingham Political Union (BPU), led by Thomas Atwood. It was agitating for political reform, notably campaigning to extend and redistribute suffrage rights to the working class, and was central to the passing of the Great Reform Bill of 1832.

To find the spot, head down to 36 George St; on your left you will see a brick wall, the parapet of the former canal bridge, with a two-window wide tall warehouse behind it and a slight bump in the road; this is where the canal (now filled in) went into the sandpit (to the right of the road) where the demonstration was held. Close your eyes, imagine and give thanks. This is where great people helped to forge our democracy.

There are several interesting listed buildings, all Grade II, in Lower Vittoria Street, which merit a look, comprising as they do a varied set of examples of Jewellery Quarter architecture.

Almost opposite Regent Street is the narrow lane known as Regent Place. A couple of hundred yards along on the right, the premises of Deakin & Francis stand out by virtue of the ‘D & F’ sign on the end wall. As recorded by the blue plaque on the front of the building, the building behind these premises is on the site of the house at Harper’s Hill that James Watt lived in for around 15 years from 1777. James Watt’s home, which was big enough to be divided into two houses when he left, was a substantial three storey, five-bayed property, which provided accommodation for Boulton & Watt’s drawing office as well as for the Watt family. James Watt conceived and designed some of his most important innovations in this house.

At the top of Vittoria St, you will see the attractive Birmingham School of Jewellery, dating back to 1890. The Birmingham Jewellers and Silversmiths Association took the lead role in setting up the school, with the aim of promoting ‘art and technical education’ among apprentice jewellers. Take a look to see if there is an exhibition on, the students’ work is often displayed.

The splendid Chamberlain Iron Clock, which serves as a landmark for the Jewellery Quarter, was presented to Joseph Chamberlain by his constituents (he was MP for this part of town) in 1903, shortly after the end of the Boer War. The Rose Villa Tavern, just behind it, has fine 1920s tiling and stained glass; a quick drink and loo break perhaps while you take a quick look?

The splendid Chamberlain Iron Clock, which serves as a landmark for the Jewellery Quarter, was presented to Joseph Chamberlain by his constituents (he was MP for this part of town) in 1903, shortly after the end of the Boer War. The Rose Villa Tavern, just behind it, has fine 1920s tiling and stained glass; a quick drink and loo break perhaps while you take a quick look?

After our quick refreshment, we sauntered down through the Warstone Lane Cemetery, which dates from 1847.  A major feature is the two tiers of catacombs, whose unhealthy vapours led to the Birmingham Cemeteries Act which required that non-interred coffins should be sealed with lead or pitch. Among several prominent Birmingham people buried here are John Baskerville, inventor of the eponymous typeface; read this fascinating story of how an atheist managed to end up buried in holy ground after an eight-year detour: More about John Baskerville.

A major feature is the two tiers of catacombs, whose unhealthy vapours led to the Birmingham Cemeteries Act which required that non-interred coffins should be sealed with lead or pitch. Among several prominent Birmingham people buried here are John Baskerville, inventor of the eponymous typeface; read this fascinating story of how an atheist managed to end up buried in holy ground after an eight-year detour: More about John Baskerville.

Exiting to the west, we saw the old Birmingham Mint building to our left, which in its heydey produced a remarkable total of one thousand million coins a year which were sold all over the world.

We now found ourselves on the Middle Ring Rd, which supposedly follows the line of the Roman road of Icknield Street, on its way from the fort and township at Metchley near Birmingham University, to Wall near Lichfield. Only those of you with the most vivid imagination will be able to see chariots trundling along this road; you will probably want to get away from it as soon as possible. The only thing the old road and the new road have in common is that they were both built by Italians, the latter in the 1960s by the man we love to criticise, Herbert Manzoni.

Anyway, you only have to put up with the company of this dual carriageway for a couple of hundred yards or so, before you can bid it a rapid farewell and escape through a pair of massive stone gateposts into the Key Hill Cemetery. This cemetery was set up in 1836 by a group of non-conformist businessmen concerned that free-church ministers were prevented from officiating at burial ceremonies in Church of England churches, and to meet the much-needed requirement for burial space.

Anyway, you only have to put up with the company of this dual carriageway for a couple of hundred yards or so, before you can bid it a rapid farewell and escape through a pair of massive stone gateposts into the Key Hill Cemetery. This cemetery was set up in 1836 by a group of non-conformist businessmen concerned that free-church ministers were prevented from officiating at burial ceremonies in Church of England churches, and to meet the much-needed requirement for burial space.

We found a cemetery that has seen better days but is full of charm nonetheless. And it is notable for being the resting place of many eminent Victorians. As Joseph Chamberlain remarked of it: “This is the most interesting place in the world to a Birmingham man.”

Then we embarked on what we soon realised was a fruitless project – trying to look for a particular headstone, in this case, Joseph Chamberlain’s (apparently Theresa May’s political hero), with no particular idea of where in the cemetery to look, no map being available, and apparently 30,000 headstones to check. Believe me, this is not a rewarding hobby.

We were on the point of giving up when I saw a figure on the far side of the cemetery apparently scrabbling in the grass. This turned out to be Margaret, a ‘Friend of Key Hill Cemetery’, one of those who had taken on the onerous task of holding back nature; she was in fact in the process of unearthing some headstones that had been lost in the undergrowth.

“Do you know much about this cemetery,” I enquired, which turned out to be a leading question as Margaret probably knows more about this spot than anyone else alive. Half an hour later, we were much better informed as to where everyone lay: to the left of us was John Skirrow Wright, the inventor of the Postal Order; just beyond him, Alfred Bird, inventor of eggless custard; squeezed between them, Joseph Gillott, a pen maker. Then we moved on to the Chamberlain family headstones (just in front of the catacombs, on the left-hand end) and saw what an extended and established family the Chamberlains had been in Birmingham. Next, we headed along the base of the Catacombs and saw the headstone of Thomas Avery (hard to say how much it weighed) and then Joseph Tangye, who helped launch Brunel’s steamship SS Great Eastern and was a founding benefactor of the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery.

Then finally, an oddity. Margaret showed us a large stone cross that had appeared to be sculpted skew-whiff; “When I first got to know the cemetery,” Margaret recalled, “I assumed it was just poor workmanship, perhaps a stonemason’s Friday afternoon job after too much liquid refreshment in the pub. But we decided to carry out some more research on it and it turned out to belong to a Wolverhampton railwayman who wanted to be buried here, alongside the Birmingham to Wolverhampton line. And although it is a cross of sorts, with its sloping horizontal it really represents a railway signal.”

Then finally, an oddity. Margaret showed us a large stone cross that had appeared to be sculpted skew-whiff; “When I first got to know the cemetery,” Margaret recalled, “I assumed it was just poor workmanship, perhaps a stonemason’s Friday afternoon job after too much liquid refreshment in the pub. But we decided to carry out some more research on it and it turned out to belong to a Wolverhampton railwayman who wanted to be buried here, alongside the Birmingham to Wolverhampton line. And although it is a cross of sorts, with its sloping horizontal it really represents a railway signal.”

We finally dragged ourselves away from these fascinating histories and departed through the equally imposing gates on the north side; turning up Key Hill Drive, and then through an enclosed passage, we were brought back with a jolt into the life and bustle of the Jewellery Quarter; a sharp contrast to the cemetery and maybe a good time for a break and a cup of coffee; or maybe treat your partner to a piece of jewellery for being so considerate as to accompany you round two cemeteries in quick succession.

And then we drifted through the Jewellery Quarter, past the Museum of the Jewellery Quarter and down Spencer St (or stick in Vyse St for a while if you feel like doing more window shopping for jewellery) and Caroline St, replete with jewellery businesses and interesting architecture. Buildings like the Frank Hawker Carpathian Silver Company Ltd at the Argosy Works in Spencer St, in a delightful Art Deco style.

And then we drifted through the Jewellery Quarter, past the Museum of the Jewellery Quarter and down Spencer St (or stick in Vyse St for a while if you feel like doing more window shopping for jewellery) and Caroline St, replete with jewellery businesses and interesting architecture. Buildings like the Frank Hawker Carpathian Silver Company Ltd at the Argosy Works in Spencer St, in a delightful Art Deco style.

We traversed St Paul’s Square again and re-joined the canal at Livery St; then headed along the canal until we reached the Aston Junction, where the Digbeth Branch Canal terminates and meets the Birmingham & Fazeley Canal. It had been the Spaghetti Junction of the nineteenth century, but today is mainly frequented by cyclists and the odd narrowboat.

We traversed St Paul’s Square again and re-joined the canal at Livery St; then headed along the canal until we reached the Aston Junction, where the Digbeth Branch Canal terminates and meets the Birmingham & Fazeley Canal. It had been the Spaghetti Junction of the nineteenth century, but today is mainly frequented by cyclists and the odd narrowboat.

The challenge for this stretch of the canal is that it’s the ‘outdoor living room’ (a concept we approve of) for the homeless community – so, under the arches, there is a multitude of empty bottles, beer cans, cardboard boxes, the apparatus of a wasted life. And during the day the benches tend to be occupied by unkempt men sunning themselves, generally looking pretty happy it must be said. In one way it shows what agreeable outside space the canal affords, but it’s also off-putting to many – I’m not sure what the solution is, but this will never be a popular thoroughfare until the issue is solved.

Eastside City Park (2.7 hectares, 6.8 acres) is an urban park located alongside the Thinktank Birmingham Science Museum on our way back from the canal to the city centre. Opened in 2012, it was the first new city centre park in Birmingham created for more than 130 years. A sign hopefully that once again we understand the vital importance of green spaces within cities.

Eastside City Park (2.7 hectares, 6.8 acres) is an urban park located alongside the Thinktank Birmingham Science Museum on our way back from the canal to the city centre. Opened in 2012, it was the first new city centre park in Birmingham created for more than 130 years. A sign hopefully that once again we understand the vital importance of green spaces within cities.

The canal water feature is charming, but on the day we walked through it was not working, an all too frequent problem in my experience with water features (similarly the Floozie with the Jacuzzi fountain had been closed).

Directly to the south of the park is a space that looks ominously open, ready for ‘redevelopment’ – well go online and you will see the vision of the HS2 terminus plonked here, running alongside the new park. The good news is if you look at the plan closely, the Grade I Curzon St Station (1838), the original terminus of both the London and Birmingham Railway and the Grand Junction Railway, hangs on doggedly to its site (no doubt saved by its listed status) and will be a feature of the new station – a symbol hopefully of how much better Birmingham has become at mixing old and new rather than simply destroying the old. It is the world’s oldest surviving piece of monumental railway architecture.

The proposed HS2 terminal is a timely reminder as we come to the end of our journey of how vital transport communications are to the landlocked Birmingham; and that this could once again give it a massive advantage in its fight to remain ‘Britain’s second city.’

Then the Selfridges building comes into view and you know you must be near the end of your journey – whether you love it or hate it, it surely is a useful landmark, visible as it is from so many different approaches.

THE ROUTE

- Head north out of New St Station, across Stephenson St and up Lower Temple St; turn right into the pedestrianised New St and follow it east, past the Rotunda on your right, to where it meets with the High St

- Take the wide pedestrian way SE down to St Martin’s Square, passing to the right (W end) of the church

- Head into the Open Market, then W through St Martin’s (covered) Market, then the Indoor Market (fish, meat) until you reach Pershore St; if the markets are closed, or you are not a market person, head instead through the Open Market space and turn right (SW) down Upper Dean St; then cross Pershore St at the pedestrian crossings

- Enter the Arcadian Shopping Centre (designed in a Chinese style) on the other side, and walk through it and up some steps to Hurst St; cross over, bear very slightly to your left, then head down the pedestrian St John’s Walk

- Turn right into Essex St, then along Horse Fair alongside the ring road, then go down into the underpass in Holloway Circus under the ring road

- Emerge on the other (west) side and head up Holloway Head

- After about 150ms, take a right turn into Blucher St, and follow it to the end, passing the Jewish Synagogue on your right

- Enter the Mailbox, which you will see opposite, just to the right of a giant desk lamp; go up to the third floor and exit past BBC Birmingham onto the raised walkway

- Keep at this level, passing the entrance to the Cube, crossing the canal by a footbridge, and then heading alongside the canal in a NW direction past the Gas St Basin to the Sea Life Centre

- When you are just past the Sea Life Centre, cut back behind it down Arena Walk; turn right at the Sea Life entrance and you will shortly be in The Central Square (trees and grass)

- Take the E exit, back to the Water’s Edge and across a pedestrian bridge over the canal to the ICC

- Walk through the ICC, and shortly you will emerge into Centenary Square, passing the new library on your left and the Hall of Memory in front of you

- Walk along Centenary Way, crossing back over the ring road, and you arrive in Chamberlain Square, which then segways into Victoria Square. Here you have the Town Hall and the Council House

- Exit Victoria Square on the eastern side, proceeding E down New St

- Take the first left into Bennett’s Hill (you will see a plaque to Edward Burne-Jones on your left), then the first right into Waterloo St, which will take you to St Philip’s Cathedral

- Walk through the churchyard and past the west end of the cathedral, exiting onto Colmore Row

- Head SW down Colmore Row, then right at Newhall St

- Take the first left into Edmund St and then a right at Eden Place; here you will see the wonderful Gothic Victorian Birmingham School of Art; and these streets have lots of great arts & craft/art deco architecture

- Take the next right up Cornwall St, and turn left when you reach Newhall St once again

- Cross the inner ring road for a third time and proceed down to the canal steps, which are just the other side of Fleet St on your left, alongside a modern overhang with pillars

- Once on the canal, head NE under Newhall Bridge, then shortly take an arched opening in a red and blue brick wall away from the canal into Water St

- You shortly come out in Ludgate Hill – turn up towards St Paul’s Church & Square; then cross the square, past the church and turn left into Brook St

- Take the second right into Graham St, then right again (N) into Vittoria St; at the end of which you turn left to reach the Chamberlain Clock in the middle of the roundabout

- Turn N here up Vyse St and then take a left into Warstone Lane (Brookfields) Cemetery. Head due west, passing the impressive Catacombs immediately on your left, and the cemetery slowly slopes down to an exit in the busy Icknield St, which you take

- Turn right here (N) and follow the dual carriageway along for 200 metres until you reach the big metal and stone gates of the Key Hill Cemetery

- Exit by the northern gates, turn right then immediately right again up Key Hill Drive

- At the end of this, you will see a passage on your left which takes you through to Hylton St; follow this street until you reach Vyse St

- Turn right here, past the Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, then take the first left into Spencer St, cross Warstone Lane and continue down Caroline St, back to St Paul’s Square

- Exit St Paul’s Square by the E side, this time into Mary Ann St

- Turn right at the end into Livery St and you will soon find the re-entrance to the canal, just after Water St on the left, marked by a white metal arch; descend the staircase and follow the canal all the way to the Aston Junction (just over 1km)

- Cross over the metal footbridge here, with a lock below you, and continue along the same canal you have been walking along, swinging SE now

- Just after Curzon St Bridge (the bridge itself is signed), turn left up some steps between two brick pillars and cross over the bridge heading SW. Stay on the right hand side and follow the delightful canal water feature alongside the Millennium Point and Thinktank

- Continue following the park as it swings round into an older, more established park that runs alongside Park St, and soon the Selfridges ‘bubble’ building will come into view

- Turn right just after the Selfridges building before the church and you will be back in St Martin’s Square again, close to the start of the walk. Re-trace your steps from here back to the station.

PIT STOPS

Cafe Opus at Ikon, 1 Oozells St, Brindleyplace, B1 2HS (0121 248 3226, www.cafeopus.co.uk) Light-flooded, minimal white space offering modern British menu and cakes in contemporary art gallery.

Bureau Bar, Colmore Row, 110 Colmore Row, B3 3AG (0121 236 1110, www.thebureaubar.co.uk) Vintage cocktail and deli bar, with roof terrace

Java Lounge Coffee House, 124 Colmore Row, Birmingham, B3 3SD (0121 347 6610 www.javaloungecoffee.com)

Vee’s Deli, 83 Vyse St, B18 6HA (0121 523 3272 www.veesdeli.co.uk) makes a good halfway breakpoint in the heart of the Jewellery Quarter. Straightforward, friendly café.

Peel and Stone, Arch 33, Water Street, Birmingham, B3 1HL (0121 572 1713 www.peelandstone.co.uk) ‘Bread, brunch & lunch’

QUIRKY SHOPPING

The Jewellery Quarter is full of interesting shops, lots of jewellery naturally, but also galleries including St Paul’s Gallery, which sells limited-edition prints by British artists and album-cover art.

Great Western Arcade, to the NE of St Philip’s Sq (B2 5HU) is an ornate relic of Brum’s Victorian heydey. Restored to its former glory, it now has some of the city’s most unusual shops, including Phil Hazel’s Liquor Store which doesn’t peddle booze but actually sells men’s apparel.

The Custard Factory is a little way out in Gibb St (B9 4AA). Adorned with murals and massive sculptures, highlights include several vintage boutiques and a splendid little record shop, Left for Dead.

PLACES TO VISIT

National Trust Back to Backs, 61-63 Hurst St, B5 4TE (0121 666 7671) is the last surviving court of back-to-back houses in Birmingham. Guided tours by appointment.

Ikon Contemporary Art, Brindleyplace, B1 2HS (0121 248 0708, www.ikonltd.com) is an internationally acclaimed contemporary art venue.

Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, Chamberlain Square, B3 3DH (0121 348 8032, www.birminghammuseums.org.uk/bmag) has the best collection of pre-Raphaelite art anywhere in the country.

Museum of the Jewellery Quarter, 75-80 Vyse St, B18 6HA (0121 348 8140 is built around a perfectly preserved jewellery workshop offering a unique glimpse of working life from the past.

Think Tank, Birmingham Science Museum, Millennium Point, Curzon St, B4 7XG (0121 348 8120, www.birminghammuseums.org.uk/thinktank) is a great family destination and there’s also a play area for younger children outside.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Walk: Birmingham’s great parks are towards the university in Edgebaston. The Ramblers have a good route there, the Three Parks Walk

Read: Free Parks for the People, A History of Birmingham’s Municipal Parks by Carl Chinn

Watch: Jonathan Mead’s Birmingham for some fun. “Other places have a love-hate relationship with cars. With Brum, it’s just love. Autoeroticism without shame, this is Motown.”

15th September 2017 at 12:36 pm

Nice speech………….

11th May 2018 at 8:08 pm

Great website and I’ll definitely be knocking some of these off. People may be interested in a 2nd city equivalent of the Capital Ring I knocked together as a little project. http://thebrummiering.weebly.com

12th May 2018 at 10:08 am

Loving the Brummie Ring – there are so many green spaces just a little further out from my central route.