The original Northern Powerhouse

Leeds is a city of industry and enterprise but also a very human-scaled town – this walk takes you through the old industrial areas, the retail district, the civic centre and the universities.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 10.2 km (6.4 miles)

- Typical time: 2 ½ hours

- Height change: 66 metres

- Start & Finish: Leeds Station (LS1 4DY)

- Terrain: all pavement; sturdy footwear recommended

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Penny Pocket Park, Merrion Gardens, Millennium Square, Nelson Mandela Gardens, Queen Square, Chancellor’s Court, University Square, St George’s Fields, Woodhouse Moor, Hanover Square, Woodhouse Square, Park Square, City Square |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Aire, Leeds & Liverpool Canal, Hol Beck |

| Stunning cityscape | Leeds Town Hall Clocktower (as part of tour), Sky Lounge (LS1 4BR), Headrow House Roof Terrace (LS1 6PU) |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | St John’s (1630s) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | The Calls (18th C), The Third White Cloth Hall (1777), Queen’s Court (18th C), Leeds Mechanics’ Institute (1824), Claremont House (1780s), Denison Hall (1786) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Leeds Bridge (1873), Leeds Minster (1841), The Corn Exchange (1863), Kirkgate Market (from 1820s), The Arcades (1800s), The Grand Theatre (1878), St Anne’s RC Cathedral (1904), Leeds Town Hall (1858), Great Hall (1894), Leeds Grammar School (1859), Leeds General Infirmary (1869), Oxford Place Methodist Church (1890s), Hotel Metropole (1897), Old Post Office (1896) |

| Industrial Heritage | Marshall’s Mill (1815), Tower Works (from 1860s), Temple Mill (1841), St Paul’s House (1878), Joseph’s Well (1888-1904). |

| Modern (post-1918) | Candle House (2009), Bridgewater Place (2005), Centenary Bridge (1993), Victoria Gate (2016), Henry Moore Institute entrance (1993), Leeds Civic Hall (1933), Leeds First Direct Arena (2013), Broadcasting Tower (2009), E C Stoner Building & Edward Boyle Library (1960s), Parkinson Building (1951), Magistrate’s Court (1994), Bank House (1969), No. 1 City Square (1998), The Queen’s Hotel (1930s) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Out of the Woods, Tiled Hall, Leeds Art Gallery, Coffee 44, Just Grand! Vintage Tearoom, Tiled Hall, Leeds Art Gallery, Fettle Café |

| Quirky Shopping | The Arcades, Kirkgate Market, The Corn Exchange |

| Places to visit | The Tetley, The Henry Moore Institute, Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds City Museum, M&S Company Archive |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Leeds Indie Food Festival (May), Leeds Walking Festival (June), Leeds Carnival (Aug), Leeds Festival (Aug), Leeds International Film Festival (Nov) |

City population: 781,700 (mid-2016 est.)

Urban population: 1,901,934 (mid-2016 est.)

Ranking: 2nd largest city in the UK (Wiki)

Date of origin: 5thC AD

‘Type’ of city: Industrial

City status: 1893

Ten famous inhabitants: H. H. Asquith (Liberal Prime Minister), The Brownlee brothers (athletes), Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (soldier), Helen Fielding (novelist – Bridget Jones’ Diary), Damien Hirst (artist), Sir Len Hutton (cricketer), Peter O’Toole (actor), Keith Waterhouse (author of Billy Liar), Marco Pierre White (celebrity chef), Ernie Wise (comedian)

Notable city architects/planners: Cuthbert Brodrick (1822-1905) – Corn Exchange, Town Hall, City Museum; Thomas Ambler (1838-1920) – St Paul’s House, St James’ Hall, Golden Lion Hotel, Joseph’s Well, the Whip Inn; John Thorp, City Architect from 1970 to 2010 – buildings & spaces he has evolved include the Civic Hall, Millennium Square, City Square, the new museum in the old Mechanics Institute, the Carriageworks Theatre and the Leonardo Building.

Number of Listed Buildings: 2,443, of which 8 are Grade I listed and 31 2* listed.

Films/TV series shot here: In 1888 Louis Le Prince filmed moving picture sequences – Roundhay Garden Scene and a Leeds Bridge street scene – using a single-lens camera and Eastman’s paper film. This is one of the earliest films ever made.

Peaky Blinders TV series (2013 – Leeds Town Hall)

Estimated % of accessible green space in the city (Eski): 22% (7th out of Top 10 cities)

THE CONTEXT

The name Leeds derives from the old Brythonic word Ladenses meaning ‘people of the fast-flowing river’, in reference to the River Aire that flows through the city.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Leeds became a major centre for the production and trading of wool. During this period John Harrison (1579-1656), a cloth merchant was one of the most influential figures, active both in politics and commerce. He was the benefactor of St John’s Church, which we pass on our walk and many other institutions.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Leeds became a major centre for the production and trading of wool. During this period John Harrison (1579-1656), a cloth merchant was one of the most influential figures, active both in politics and commerce. He was the benefactor of St John’s Church, which we pass on our walk and many other institutions.

During the Industrial Revolution, Leeds developed into a major mill town; wool was the dominant industry but flax, engineering, iron foundries, printing, and other industries were also important. During the 19th century, the town became established as one of the world’s most important engineering centres, notably in the area of steam locomotives. At one point it accounted for a fifth of the UK’s exports.

From being a compact market town in the valley of the River Aire in the 16th century, Leeds expanded and absorbed the surrounding villages as the industrial revolution took off. But it didn’t expand at the helter-skelter speed of say a Manchester, and this is reflected in a built environment that sits midway between a solid regional town and a booming city. It doesn’t quite have the thrusting feel and urgency of Manchester, it feels like a place that had a story before the industrial revolution began, and has always been inhabited by solid Yorkshire stock.

Leeds really ‘came of age’ as a great city in the second half of the nineteenth century. The new Town Hall, admired throughout the Empire and a model for numerous other civic buildings, was opened by Queen Victoria in 1854. And to cap it all, Leeds achieved city status in 1893.

Piqued into action by their smaller and younger neighbour Sheffield, who had applied for city status in 1892, Leeds Town Council launched its own petition in 1893 setting out the reasons it was felt that they deserved to become a city: these were the antiquity of the town, its many charters, its large area, its population that was ‘approaching 400,000’, the fact that it was the largest municipality not to be a city, its commercial importance for the woollen industry, the fact it was the only university town not a city, and that Leeds and Sheffield were the only boroughs returning five MPs to the House of Commons without the status of a city.

The Home Secretary forwarded the petitions of both towns to the Queen, recommending that the honour be granted in both cases as they were the “only towns in the United Kingdom with a population exceeding 300,000 to which the title of City, enjoyed by many smaller or less important places, has not been granted; and that both appear to be well fitted by their loyalty, public spirit, and industrial progress, for this mark of your Majesty’s favour.” She assented, and both Leeds and Sheffield became cities in 1893. In recognition of their new-found status, Leeds re-developed City Square to make it grander and more befitting of a city. It was a city that was proud of itself, and this is reflected in the architecture. As John Betjeman observed; “No city in the North of England has so fine a swagger in the way of 19th-and early 20th-century architecture as Leeds, whether it is in churches, mills, shops or private houses, stone, brick or terra cotta.” We get to see many fine examples of these in today’s walk.

In the 1920s, Leeds also became one of the first cities outside London to start to plan the way it was laid out rather than letting things happen willy-nilly. The Headrow was created as an east-west link between Mabgate and the Town Hall to relieve traffic congestion, to create a ‘planned’ civic route and get rid of slum housing; and the Outer Ring Road was also started.

In 1964, the dreadful Inner Ring Road was built, but at least the university was successful in lobbying to get the road sunk below ground level. The problem of Leeds traffic had been the subject of a case study in Buchanan’s influential 1963 report on Traffic on Cities, in which he famously said: “It is impossible to spend any time on the study of the future of traffic in towns without at once being appalled by the magnitude of the emergency that is coming upon us. We are nourishing at immense cost a monster of great potential destructiveness, and yet we love him dearly. To refuse to accept the challenge it presents would be an act of defeatism.” The report gave planners a set of policy blueprints to deal with its effects on the urban environment, including traffic containment and segregation, which could be balanced against urban redevelopment, new corridor and distribution roads and precincts. Apparently, it inspired the thinking behind the review of the Leeds Development Plan in 1965-1968. Sadly, although Buchanan’s analysis was undoubtedly correct, his proposed solutions were not, leading to much of the damage caused to UK cities in the 60s and 70s from which they are only piece by piece being rescued from.

One thing that did go very right for Leeds, however, was the switch from manufacturing to services as manufacturing inevitably declined. It became the biggest centre of legal and financial services outside London and, more recently, has also been at the forefront of the digital economy and call centres. It now has the most diverse economy of all the UK’s main employment centres and has seen the fastest rate of private sector jobs growth of any UK city.

Education is also a vital part of the mix. The University of Leeds, Leeds Beckett University Leeds Trinity University have nearly 60,000 students between them, adding hugely to the life and vitality of the city.

In fact, in 2017 The Times voted Leeds as the number one cultural place to live in Britain, citing amongst other attractions Opera North, the Northern Ballet and the West Yorkshire Playhouse. And Lonely Planet ranked in the Top 10 best places in Europe to visit in 2017. You get a sense of this creative energy as you walk around.

THE WALK

Our walk started by going the wrong way out of the station and the long way around. Don’t make this rookie error. Take the exit from the station by Platform 17, intriguingly marked ‘Dark Arches’.

Amazingly, they are exactly what they say on the tin. The New Station (1869) was built on arches that span the River Aire, Neville Street and Swinegate. Over 18 million bricks were used during their construction – and the arches became known as ‘The Dark Arches’. They have a cavernous and eerie feeling about them that take you back in time – you half expect to bump into a Dickens’ character with a lantern around the next corner.

Amazingly, they are exactly what they say on the tin. The New Station (1869) was built on arches that span the River Aire, Neville Street and Swinegate. Over 18 million bricks were used during their construction – and the arches became known as ‘The Dark Arches’. They have a cavernous and eerie feeling about them that take you back in time – you half expect to bump into a Dickens’ character with a lantern around the next corner.

The Leeds & Liverpool Canal starts at this point as an offshoot of the River Aire. In the mid-18th century, the growing towns of Yorkshire were trading increasingly. While the Aire and Calder Navigation improved links to the east for Leeds, links to the west were limited. Bradford merchants wanted to increase the supply of limestone to make lime for mortar and agriculture using coal from Bradford’s collieries and to transport textiles to the Port of Liverpool. On the west coast, traders in the busy port of Liverpool were looking for a cheap supply of coal for their shipping and manufacturing businesses and to tap the output from the industrial regions of Lancashire. A canal across the Pennines linking Liverpool and Hull (by means of the Aire and Calder Navigation) would have obvious trade benefits. It was constructed over a period of 50 years, from the 1770s onwards. The most important cargo was always coal, with over a million tons per year being delivered to Liverpool in the 1860s.

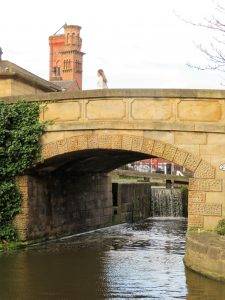

The quaint Leeds and Liverpool Canal Office, and the stone bridge over the canal that we cross, were both built in 1841. The bridge provided access from the canal wharves to the mills and factories south of the canal.

The quaint Leeds and Liverpool Canal Office, and the stone bridge over the canal that we cross, were both built in 1841. The bridge provided access from the canal wharves to the mills and factories south of the canal.

Candle House (2009) is one of the most recognisable modern buildings on the Leeds skyline. It uses an unusual twisted brickwork style that makes the tower appear to lean. It comprises 160 flats, a ground floor restaurant and a garden roof terrace (I think you have to know a resident to gain access), decked out in stylish fashion, with coloured sheds, hammocks, bean bags and brightly coloured seating. The building was named after the candle and tallow packing warehouses that used to be located here, as well as of course its shape.

Candle House (2009) is one of the most recognisable modern buildings on the Leeds skyline. It uses an unusual twisted brickwork style that makes the tower appear to lean. It comprises 160 flats, a ground floor restaurant and a garden roof terrace (I think you have to know a resident to gain access), decked out in stylish fashion, with coloured sheds, hammocks, bean bags and brightly coloured seating. The building was named after the candle and tallow packing warehouses that used to be located here, as well as of course its shape.

We cross the Hol Beck  stream, which used to take a meandering path across the flood plain stream but now flows along a rather uninspiring culvert. Its waters were originally believed to have spa properties but were then largely used to power the many mills that were built around here. But it could also be seen as a magical stream as it is the start of a Disney-like journey through an industrial area peppered with classical civilisation associations. The Holbeck Conservation Area includes several industrial archaeological sites and 32 Listed buildings. It is unique in the city as an area where many 19th century industrial buildings survive in an unaltered group within the original street pattern.

stream, which used to take a meandering path across the flood plain stream but now flows along a rather uninspiring culvert. Its waters were originally believed to have spa properties but were then largely used to power the many mills that were built around here. But it could also be seen as a magical stream as it is the start of a Disney-like journey through an industrial area peppered with classical civilisation associations. The Holbeck Conservation Area includes several industrial archaeological sites and 32 Listed buildings. It is unique in the city as an area where many 19th century industrial buildings survive in an unaltered group within the original street pattern.

Tower Works used to be a factory making steel pins for carding and combing in the textile industry. The design of its three extraction towers was heavily influenced by the owner’s love of Italian architecture and art. The largest and most ornate tower (1899, by Bakewell) is based on Giotto’s Campanile in Florence. The smaller ornate tower (1866, by Shaw) is styled after the Torre dei Lamberti in Verona. A third plain tower (1919) represents a Tuscan tower house. And from the south side, there is now a fourth tower in matching red brick – the ‘Leaning Tower of Pisa’ aka the Candle House – surely no coincidence in architectural terms!!

The factory site has recently been re-developed as part of the Holbeck Urban Village scheme and now has tenants including a creative brand agency, a costume designer and a digital design agency, all testament to Leeds’ successful shift to modern service industries.

Marshall’s Mill was part of a complex begun in the 1790s by industrial pioneer John Marshall. It comprised several mills, including the six-storey mill on our right dating from 1815-16. Very much what you would expect a mill to look like in fact, with serried ranks of windows on every storey.

But then suddenly on our right, we are confronted by what appears to be an Egyptian temple. And for those of you Egyptophiles, you will of course immediately recognise it as a copy of the Temple of Horus at Edfu. This was the office building of the Temple Works, built between 1838–41; and further along the road is the factory itself, apparently derived from the Typhonium at Dendera.

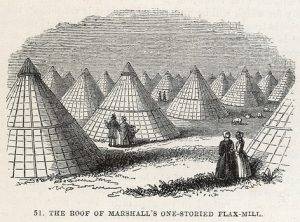

The Marshalls, in common with many well-to-do gentry of the era, had a fascination for Egyptology and would also have been aware that flax originally came from Egypt. When it was completed, it was one of the largest factories in the world, with two-acres of factory floor employing over 2,000 workers and utilising 7,000 steam-powered spindles to manufacture flax. As well as its nod to Egypt it was highly innovative in structure being single storey, sharply improving productivity as goods did not have to be taken up and down stairs. And in the undercroft, there were many facilities for the workers, including cold & hot baths (cold free, hot 1d), dormitories, shops, doctors and a church and a school above ground.

A curious feature of the Temple Works building is that sheep used to graze on the grass-covered roof with its 65 conical skylights, long before in recent years the Rurbanites cottoned on to the idea of sheep on urban roofs. The reason to have grass on the roof was to wick the moisture from the air to help retain the humidity in the flax mill, thus preventing the linen thread from becoming dried out and unmanageable. The sheep were the ‘mowers’. Apparently, this also led to the invention of the hydraulic lift. The sheep had to get down from time to time and they couldn’t climb ladders.

The site has had a chequered history since the Marshalls went bankrupt in the 1880s and has most recently been used as a cultural centre. It has serious structural problems and is not in a good state of repair, but hopefully, architectural salvation will come in the shape of fashion brand Burberry, who want to open a weaving centre here. The company aims to open a £50m site at Temple Works by 2019, creating 200 jobs to produce trench coats. And a grant of up to £750,000 will be provided to create a ‘new public space’ at the front of Temple Works, so hopefully a good solution all round.

We then cut back through Saw Mill Yard and Foundry St, re-developed industrial areas. As we come out back on Water Lane and turn right, so Bridgewater Place, nicknamed ‘The Dalek’, looms into full view. It is the tallest building in Yorkshire (Leeds likes to be ‘top dog’ in these parts) and is visible from up to 25 miles away. In 2008, Building Design, the architectural journal, shortlisted Bridgewater Place for its annual Carbuncle Cup, which is awarded to ‘buildings so ugly they freeze the heart’. I doubt you will much dispute this view.

As if poor looks weren’t a sufficient handicap, the building also has a major design flaw. Its shape accelerates winds in its immediate vicinity, knocking over pedestrians and even vehicles. Initially, roads nearby were closed to vehicles when wind speeds exceeded 45 mph and some of the entrances to the building were closed for safety reasons. But recently it has been deemed necessary to construct a system of massive wind-deflecting canopies and screens at the site.

As if poor looks weren’t a sufficient handicap, the building also has a major design flaw. Its shape accelerates winds in its immediate vicinity, knocking over pedestrians and even vehicles. Initially, roads nearby were closed to vehicles when wind speeds exceeded 45 mph and some of the entrances to the building were closed for safety reasons. But recently it has been deemed necessary to construct a system of massive wind-deflecting canopies and screens at the site.

Anyway, we survived the wind tunnel (merely rustling leaves on the day we passed) and crossed over Lock 1 and along the north bank of the river heading down to Leeds Bridge (1873), a rather fine Victorian cast iron bridge. The cast iron balustrade is of rings and flowers. The east side bears the arms of the Corporation of Leeds (crowned owls and fleece). The western side has the names of civic dignitaries on a plaque.

This was the original centre of Leeds and there has been a bridge here since medieval times and before that a ferry. The medieval town was centred on 13th-century burgess building plots either side of a wide road from this river crossing called Bridge Gate, now Briggate. A wool cloth market operated at Leeds Bridge, becoming the centre of wool trade for the West Riding of Yorkshire in the late 17th century.

This was the original centre of Leeds and there has been a bridge here since medieval times and before that a ferry. The medieval town was centred on 13th-century burgess building plots either side of a wide road from this river crossing called Bridge Gate, now Briggate. A wool cloth market operated at Leeds Bridge, becoming the centre of wool trade for the West Riding of Yorkshire in the late 17th century.

In 1888 Louis Le Prince made a pioneering moving picture recording of Traffic Crossing Leeds Bridge from an upstairs window of No 19 Bridge End (SE end of the bridge). You can watch it at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g3AbI6rs8XQ (don’t get too excited).

Then we strolled along the historic Dock St, which has a row of mid-18th-century merchant houses and warehouses on the south side. Tetley’s Brewery Wharf at the end of the street is now a major residential development

The Centenary Bridge is not a bridge of such great beauty compared to the many Millennium bridges we have walked past or over (think London, Newcastle, Worcester for example). And the killjoys of the council decided that the ‘love lock padlocks’ that had been proliferating on the bridge represented a structural risk and removed them all back in 2016. Very thoughtfully the Council posted: “Anyone who has placed a lock on the bridge will be able to claim it back, as the council will be keeping them under lock and key for three months.” If love-locks are your thing then this little dissertation certainly merits a look: https://lovelockdiaries.wordpress.com/2015/04/23/love-locks-in-leeds/ I feel they may have improved the look of this rather dull bridge. But anyway, we should celebrate its convenience and reason for being here, opened in 1993 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Leeds gaining city status.

The Centenary Bridge is not a bridge of such great beauty compared to the many Millennium bridges we have walked past or over (think London, Newcastle, Worcester for example). And the killjoys of the council decided that the ‘love lock padlocks’ that had been proliferating on the bridge represented a structural risk and removed them all back in 2016. Very thoughtfully the Council posted: “Anyone who has placed a lock on the bridge will be able to claim it back, as the council will be keeping them under lock and key for three months.” If love-locks are your thing then this little dissertation certainly merits a look: https://lovelockdiaries.wordpress.com/2015/04/23/love-locks-in-leeds/ I feel they may have improved the look of this rather dull bridge. But anyway, we should celebrate its convenience and reason for being here, opened in 1993 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Leeds gaining city status.

There was a church on the site of Leeds Minster (St Peter’s) since the 7th century, but the one we see today is early Victorian Gothic, consecrated in 1841 and at the time the largest church built in England since St Paul’s. More importantly, it was the first great ‘town church’, intended to minister to the increasingly disillusioned working classes of the Industrial Revolution (but as we shall see later in the walk, the non-Conformists were really more successful at this).

There was a church on the site of Leeds Minster (St Peter’s) since the 7th century, but the one we see today is early Victorian Gothic, consecrated in 1841 and at the time the largest church built in England since St Paul’s. More importantly, it was the first great ‘town church’, intended to minister to the increasingly disillusioned working classes of the Industrial Revolution (but as we shall see later in the walk, the non-Conformists were really more successful at this).

Penny Pocket Park was once part of the old graveyard. It had stopped being used for burials in the 1830s, as like most urban churchyards it was overflowing; and a new cemetery was laid out in St George’s Field, which we pass through later. But when the construction of the New Station began in 1866, it became clear that the route to Selby would need to pass through the old graveyard, and it was agreed that the railway would be built on a solid embankment, with the gravestones on a slope – it makes for a rather unusual sight. Organic or just plain odd – you take your pick. One blogger puts it very poetically; “The undulating topography of gravestones and trees.” To me, the park just looks a bit of a mess. Sorry!

Next stop The Calls. The Calls area, along with neighbouring Clarence Dock, served as docks on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the Aire and Calder Navigation throughout the industrial revolution and the early 20th century. The waterways would have teemed with barges, cranes and warehouses and buzzed with forgers, malters, brewers and stone merchants. You will see on your left several of the old warehouses. Once a thriving 18th-century flour mill, 42 the Calls has been converted into a luxury hotel, boasting original beamed ceilings, working mill machinery and elegantly exposed brickwork. That could be a good place to stay…

Just after the railway viaduct in Call Lane is Queen’s Court, a 18th-century house built for wealthy wool merchants. The buildings we first come to housed cloth finishing and packaging workshops and warehouses and this alleyway follows the line of a medieval lane at the back of the original burgage plots.

As we head up Briggate, we peered into Lambert’s Yard on our right, which boasts Leeds’ oldest surviving timber frame building. It’s the last surviving triple-storey house in the centre of Leeds, and a historical and architectural gem, the house, originally built around 1600; the Lambert family were wealthy grocers and tea dealers.

Time Ball Buildings across the road is a lot of fun. The original building dates from the early 19th century and John Dyson, a watchmaker, elaborately redecorated the front in the 1870s. The distinctive features of the building are the gilded time ball, and the cantilevered clock, surmounted by a figure of Father Time.

Time Ball Buildings across the road is a lot of fun. The original building dates from the early 19th century and John Dyson, a watchmaker, elaborately redecorated the front in the 1870s. The distinctive features of the building are the gilded time ball, and the cantilevered clock, surmounted by a figure of Father Time.

Then sharp right along Hirst’s Yard, an alleyway that has two-storey brick workshops complete with hoist, loading door and bollards, providing a good impression of its character in the early 19th C. The neo-Tudor Hirst Yard Bar (formerly the Whip Inn) is by Thomas Ambler.

Then one of Leeds’ most fabulous and unusual buildings, The Corn Exchange. Designed by Cuthbert Brodrick, best known for Leeds Town Hall, this Grade I listed structure was opened in 1863. He took as his model the Halle au Blé in Paris, built in the 1760s.

It is one of the finest examples of Victorian commercial architecture in the country – on the exterior, the bold diamond-pointed rustication of its masonry, on the interior two tiers of arches in coloured and moulded brickwork, each giving access to a corn factor’s offices, the upper tier being served by a broad gallery with cast-iron railings. Above rises the great elliptical dome, a masterpiece of Victorian engineering. The large glazed panels were designed to provide the optimum quality of natural lighting on to the floor below so that those trading at the small black desks could accurately judge the quality of the grain.

It is one of the finest examples of Victorian commercial architecture in the country – on the exterior, the bold diamond-pointed rustication of its masonry, on the interior two tiers of arches in coloured and moulded brickwork, each giving access to a corn factor’s offices, the upper tier being served by a broad gallery with cast-iron railings. Above rises the great elliptical dome, a masterpiece of Victorian engineering. The large glazed panels were designed to provide the optimum quality of natural lighting on to the floor below so that those trading at the small black desks could accurately judge the quality of the grain.

In 1990, it was converted for shopping and leisure use, which involved cutting out a section of the ground floor to make the basement into a restaurant, sadly currently vacant, with shops on the ground and mezzanine levels. Can’t quite put my finger on it, but it’s missing something, maybe footfall.

As we head round the back of the Corn Exchange we see The Third White Cloth Hall (1777), built at a time when the industry was thriving and three-quarters of the cloth passing through Leeds was exported. The Cupola from the demolished 2nd White Cloth Hall was installed on the roof in 1786. But when the new North-Eastern Viaduct came the building was literally sliced in half.

Now we are really in the commercial heart of the city, and next up is the Kirkgate Market, the largest covered market in Europe. The market first opened in 1822 as an open-air market, and between 1850 and 1875 the first covered sections were added. In 1884, it was the founding location of Marks & Spencer which opened as a penny bazaar. The Marks & Spencer’s heritage is marked by the Market Clock in the 1904 hall which bears the shop’s name.

The 1904 Hall is the most ornate of the halls and is situated at the front of the complex, the route we take. It has a grand Flemish style frontage with Art Nouveau details – shop fronts below, offices above and an extravagant skyline of towers, turrets and chimneys. Behind this amazing façade is an even more striking market hall with clustered cast iron Corinthian columns supporting a glazed clerestory, lantern roofs and a central octagon. Dragons support the balcony; the walls are glazed brick. Somehow this old-fashioned market has survived the onset of retail centres, hosting 800 stalls and typically having more than 100,00 visitors on a Saturday. It has gone decidedly up-market in recent years (not to everyone’s liking – it is no longer quite the hub of the community that it once was), with artisan coffee producers and the like increasingly to the fore.

The 1904 Hall is the most ornate of the halls and is situated at the front of the complex, the route we take. It has a grand Flemish style frontage with Art Nouveau details – shop fronts below, offices above and an extravagant skyline of towers, turrets and chimneys. Behind this amazing façade is an even more striking market hall with clustered cast iron Corinthian columns supporting a glazed clerestory, lantern roofs and a central octagon. Dragons support the balcony; the walls are glazed brick. Somehow this old-fashioned market has survived the onset of retail centres, hosting 800 stalls and typically having more than 100,00 visitors on a Saturday. It has gone decidedly up-market in recent years (not to everyone’s liking – it is no longer quite the hub of the community that it once was), with artisan coffee producers and the like increasingly to the fore.

Victoria Gate (2016) is pretty appealing as modern shopping centres go, with a striking landmark John Lewis building, taking design cues from the surrounding markets and arcades. The external grid pattern is apparently inspired by Leeds’ traditions of manufacturing textiles, whilst the new arcade roof has strong echoes of the Corn Exchange roof.

The Guardian’s Rowan Moore’s sums it up well: “It’s entertaining. It energises. Like its predecessors, it shows how shopping can enhance a city, not kill it.”

The Guardian’s Rowan Moore’s sums it up well: “It’s entertaining. It energises. Like its predecessors, it shows how shopping can enhance a city, not kill it.”

The Arcades are one of Leeds’ great joys, bustling and busy with shoppers to this day. They were built around 1900 and designed by the theatre architect Frank Matcham; and originally included the Empire Palace Theatre, which was sadly demolished in the 1960s. The exteriors are mainly of faience from the Burmantofts Pottery, and the interiors of the arcades contain several mosaics and plentiful use of marble. The arcades were built to appeal to the affluent middle-class and were a safe place away from the hustle and bustle of the grimy streets where one could see and be seen by the Leeds gentry. This fashion for arcades spread right across the country during this period (try our Cardiff or Newcastle urban rambles for other great examples).

Heading north now across Headrow, we head up New Briggate and take a left through an arch into St John’s Churchyard. But just before we do that, glance across the road at The Grand Theatre (1878). The exterior is in a mixture of Romanesque and Scottish baronial styles, while the interior has such Gothic motifs as fan-vaulting and clustered columns. The theatre is home to Opera North and is regularly visited by Northern Ballet.

Heading north now across Headrow, we head up New Briggate and take a left through an arch into St John’s Churchyard. But just before we do that, glance across the road at The Grand Theatre (1878). The exterior is in a mixture of Romanesque and Scottish baronial styles, while the interior has such Gothic motifs as fan-vaulting and clustered columns. The theatre is home to Opera North and is regularly visited by Northern Ballet.

St John’s is the oldest church in the city, built in 1632-34 at a turbulent time when very few churches were constructed. The glory of the church lies in its magnificent Jacobean fittings, particularly the superb carved wooden screen. Every part of the screen is richly decorated with flowers, hearts, twisting vines and grotesque heads of humans and animals. There is more carving on the wall panels, pews and pulpit. Brightly painted angels play instruments in the roof and look down on carved pews below.

St John’s is the oldest church in the city, built in 1632-34 at a turbulent time when very few churches were constructed. The glory of the church lies in its magnificent Jacobean fittings, particularly the superb carved wooden screen. Every part of the screen is richly decorated with flowers, hearts, twisting vines and grotesque heads of humans and animals. There is more carving on the wall panels, pews and pulpit. Brightly painted angels play instruments in the roof and look down on carved pews below.

Merrion Gardens, one of only a few public green spaces in the city centre, was originally laid out as a memorial to Thomas Wade who, in 1530, left a will that stipulated that the money be used to benefit the people of Leeds.

The space has recently been subject to a complete overhaul, saving it from the dual ravages of tree roots forcing their way up through the paved areas and anti-social behaviour making it an unwelcoming spot. A reminder of the challenges that a council faces in keeping a piece of green space open and welcoming. The day we passed through it was full of lunch breakers relaxing in the sunshine.

St Anne’s RC Cathedral is a wonderful essay in Arts and Crafts Gothic, completed in 1904. The reredos of the old cathedral’s high altar was designed by Pugin in 1842 and moved here.

St Anne’s RC Cathedral is a wonderful essay in Arts and Crafts Gothic, completed in 1904. The reredos of the old cathedral’s high altar was designed by Pugin in 1842 and moved here.

Headrow used to be a mediaeval route connecting the east to the west of the city. It was subject to a major re-development scheme in the 1920s, masterminded by Reginald Blomfield, who had also been responsible for the extensive re-design of Regent Street in London. The Headrow scheme, which became known as the ‘Regent Street of the North’, served both to widen the road and to create a ‘planned’ civic route with buildings in a defined style on either flank. In the event, given the Great Depression followed soon after, only some of the buildings were constructed, and what you have today is a series of impressive but rather bland neo-classical buildings along a traffic-laden avenue. It represented, nonetheless, the first attempt outside London to create a planned structure for a city and reflected Leeds’ civic ambitions. The Permanent House in Headrow (just to the east of our path) looks exactly like the Quadrant in Regent Street.

The Henry Moore Institute has an impressive new entrance, a bold polished black granite façade with a single very vertical opening. Although modest it is one of the most stylish additions to modern Leeds, designed by Dixon Jones in 1993, who also designed the extension to the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden.

Henry Moore was the son of a Yorkshire coal miner. In 1919, he became a student at the Leeds School of Art (now Leeds College of Art), which set up a sculpture studio especially for him. At the college, he met Barbara Hepworth, a fellow student who would also become a well-known British sculptor, and began a friendship and gentle professional rivalry that lasted for many years.

The Institute is a part of The Henry Moore Foundation which was set up in 1977 by Henry Moore to encourage appreciation of the visual arts, especially sculpture. In his words: “The Foundation has two or three main purposes. One is to help the appreciation of sculpture generally because I remember that as a young sculptor, there was nothing; there wasn’t a single piece of sculpture in my hometown… Leeds Art Gallery had nothing of any value. Another purpose is to look after my own work after I’m gone: probably exhibit it and also keep some of my things in suitable places in nature.”

In front of the Institute is Victoria Gardens. The area was totally refurbished in 2011 as the flagship project of the M&S Greener Living Spaces initiative, celebrating their birth in Leeds Kirkgate Market over 125 years ago.

We walk past the Leeds Art Gallery to stand alongside perhaps Leeds’ most famous building and symbol of the Victorian age, the Leeds Town Hall (1853). It was built by architect Cuthbert Brodrick, and opened by Queen Victoria, highlighting its status as an important civic structure. It is a Grade I listed building and became a model for civic buildings across Britain and the British Empire.

We walk past the Leeds Art Gallery to stand alongside perhaps Leeds’ most famous building and symbol of the Victorian age, the Leeds Town Hall (1853). It was built by architect Cuthbert Brodrick, and opened by Queen Victoria, highlighting its status as an important civic structure. It is a Grade I listed building and became a model for civic buildings across Britain and the British Empire.

The loyal address to Queen Victoria by the Town Hall Committee shows just how important the project was to civic pride: “We venture to hope that so excellent a judge of art as Your Majesty may find something to approve in the Hall in which we are now for the first time assembled, and may well be pleased to see a stirring and thriving seat of English industry embellished by an edifice not inferior to those stately piles which still attest opulence of the great commercial cities of Italy and Flanders.”

The Town Hall epitomises Leeds, and its profile is used nationally as a symbol of municipal pride and enterprise. Pevsner said: “Leeds can be proud of its Town Hall …. of the classical buildings of its date no doubt the most successful.”

Millennium Square is one of those ‘prairie’ squares which has been left ‘intentionally blank’ so that lots of events, festivals and fairs can take place there; but when there is nothing going on, it looks rather, well, empty. It was Leeds’ flagship re-development project to mark the year 2000. In 2001 Nelson Mandela appeared on stage in the square to re-dedicate the adjoining Nelson Man dela Gardens, which he described in these words: “For me to see this garden reminds me of my childhood and the happy days associated with childhood. That’s one thing that makes me be in peace with myself, to be in peace with the entire world and to be in peace with the people of Leeds. I thank you very much.” The garden as a place of repose in a busy city.

dela Gardens, which he described in these words: “For me to see this garden reminds me of my childhood and the happy days associated with childhood. That’s one thing that makes me be in peace with myself, to be in peace with the entire world and to be in peace with the people of Leeds. I thank you very much.” The garden as a place of repose in a busy city.

Leeds City Museum on the east side of the square was formerly the Leeds Mechanics’ Institute, built by Cuthbert Broderick in 1824. The objective of the Mechanics’ Institutes was to provide a technical education for the working man and for professionals to ‘address societal needs by incorporating fundamental scientific thinking and research into engineering solutions’. By 1850 there were over 700 Mechanics’ Institutes in the UK and abroad, many of which developed into libraries, colleges and universities. Leeds is a case in point, becoming the Leeds School of Art.

Leeds Civic Hall was built by Vincent Harris (lead architect of the original Exeter University campus) in 1933. This was in the depths of the Great Recession and the building was used as a piece of Keynesian job creation to stimulate the economy.

I love the golden owls’ sculptures, the emblem of Leeds. It’s surprising to find out that they were in fact added only in 2000, based on a pair of originals on the roof, and are by John Thorp, the last to hold the title of Civic Architect in the UK before his retirement in 2010. The role of civic architect in Leeds had its roots in the 1870 Education Act and a decision by the city’s School Board to appoint an architect to oversee the building of new schools. John Thorp has been widely lauded as the man who shaped modern Leeds. His philosophy was to examine and understand what already exists, looking for ways to improve or enhance it rather than sweep things away and bring in the new. He called the exercise ‘urban dentistry’. He based all development around eight key principles, one of which is about being ‘connected’ and another about being ‘re-connected’. In his words; “The city centre contains a rich variety of streets, squares, yards and arcades. This well-connected characteristic is translated into a principle for the guidance of new development and the renaissance of existing localities.” And under re-connectedness: “19th & 20th-century transportation infrastructure connected towns and cities for the movement of people and goods whilst in place disconnecting neighbourhoods and cutting across walkways, cycleways, streets and open spaces. The principle of re-connection is the most challenging but essential ingredient to the realisation of a compact, sustainable and well-connected community.” All very good for walking through a city to work or play.

I love the golden owls’ sculptures, the emblem of Leeds. It’s surprising to find out that they were in fact added only in 2000, based on a pair of originals on the roof, and are by John Thorp, the last to hold the title of Civic Architect in the UK before his retirement in 2010. The role of civic architect in Leeds had its roots in the 1870 Education Act and a decision by the city’s School Board to appoint an architect to oversee the building of new schools. John Thorp has been widely lauded as the man who shaped modern Leeds. His philosophy was to examine and understand what already exists, looking for ways to improve or enhance it rather than sweep things away and bring in the new. He called the exercise ‘urban dentistry’. He based all development around eight key principles, one of which is about being ‘connected’ and another about being ‘re-connected’. In his words; “The city centre contains a rich variety of streets, squares, yards and arcades. This well-connected characteristic is translated into a principle for the guidance of new development and the renaissance of existing localities.” And under re-connectedness: “19th & 20th-century transportation infrastructure connected towns and cities for the movement of people and goods whilst in place disconnecting neighbourhoods and cutting across walkways, cycleways, streets and open spaces. The principle of re-connection is the most challenging but essential ingredient to the realisation of a compact, sustainable and well-connected community.” All very good for walking through a city to work or play.

In Leeds, you get few if any of the ‘starchitecture’ buildings of a city such as Birmingham, but as a result, you have a city that is comfortable in its own skin and has an identity that has evolved rather than jolted from one style or belief to another.

Before we head to the two universities, we couldn’t resist a short diversion to a close-by Georgian square, Queen Square, built between 1806-22, each house originally having access to warehouses and workshops at the rear. Late 19th-century gas lamp posts with fluted shafts complete the scene. It is an architectural oasis in this part of town, but that doesn’t in anyway detract from its charm and tranquillity.

Before we head to the two universities, we couldn’t resist a short diversion to a close-by Georgian square, Queen Square, built between 1806-22, each house originally having access to warehouses and workshops at the rear. Late 19th-century gas lamp posts with fluted shafts complete the scene. It is an architectural oasis in this part of town, but that doesn’t in anyway detract from its charm and tranquillity.

Just across the way is the Leeds First Direct Arena, a 13,500-capacity entertainment arena. Opened in 2013, it makes excellent use of limited space. Naturally enough John Thorp had a hand in that too. He observed that it is particularly close in format to the Greek arena at Epidaurus. In both cases, the most distant seat is approximately 67 metres from the stage area.

The university campuses

Having said there were few ‘starchitecture’ style buildings in Leeds, I immediately, of course, have to eat my words as we see the spectacular Broadcasting Tower (2009) across the road on the Leeds Beckett campus. It is clad in weathering Corten steel, which intentionally makes it look as if it is rusting away (The Angel of the North is made of the same material). The owners, Unite, are one of the UK’s largest operators of purpose-built student accommodation.

Having said there were few ‘starchitecture’ style buildings in Leeds, I immediately, of course, have to eat my words as we see the spectacular Broadcasting Tower (2009) across the road on the Leeds Beckett campus. It is clad in weathering Corten steel, which intentionally makes it look as if it is rusting away (The Angel of the North is made of the same material). The owners, Unite, are one of the UK’s largest operators of purpose-built student accommodation.

Then we have to cross over the Inner Ring Road, and my sentiments at this point echo those of Jones the Planner: “The two campuses are divided by the motorway in a cutting that, in theory, retains the connectivity of the traditional streets above. But you are crossing a chasm of traffic noise, dodging convoluted slip roads and counter-intuitive traffic systems. And the scale of the demolitions, not just for the motorway but of the inner-city streets themselves, in reality, creates a total disconnect. In Hamburg, long sections of the urban motorway are being decked over to reconnect the dislocated city and transform the local environment. This could be done here too, with the road system simplified to create an urban grain of city streets and squares, releasing development sites and enabling new green spaces.”

Still, once we made it to the University of Leeds campus we discovered a thing of beauty, the many buildings representing a sort of history of architecture. It compises a mixture of Georgian, Gothic Revival, Art Deco, Brutalist, Postmodern and Eco-buildings, making it one of the most diverse university campuses in the country in terms of building styles and eras. In the words of Maurice Beresford, “a free open-air museum of architectural and social history”. It’s my favourite university campus that I have seen anywhere on my urban rambles.

The Historic England listing entry is a neat summary of all that is good about the first collection of buildings we pass:

The E C Stoner Building, Computing Building, Earth Sciences/Mathematics Building, Senior Common Room, Garstang Building, Manton Building and Edward Boyle Library, all designed in the 1960s and 1970s by Chamberlin Powell and Bon at Leeds University, are recommended for designation at Grade II for the following principal reasons:

The E C Stoner Building, Computing Building, Earth Sciences/Mathematics Building, Senior Common Room, Garstang Building, Manton Building and Edward Boyle Library, all designed in the 1960s and 1970s by Chamberlin Powell and Bon at Leeds University, are recommended for designation at Grade II for the following principal reasons:

* Architectural interest: they are excellent examples of post-war architectural design as influenced by Le Corbusier, both in their structural design using reinforced concrete and in their clean and sweeping lines used on a grand scale; they form a distinctive group, linked stylistically as well as physically, with repeated structural patterns of concrete beams and continuous glazing

* Influence: they were highly influential as a model for other university campuses, in their genesis in an overall master plan based on research into student movements and the use of different facilities. Chamberlin Powell and Bon were an influential and important architectural practice who completed a number of large, high-profile projects which both influenced and were influenced by their work at Leeds

* Planning: they represent a coherent attempt to create a rationalised ‘megastructure’, by linking all the elements with covered walkways, paved areas and a unified design

* Intactness: they have survived largely intact, given the changing needs of the university environment, owing to the flexibility built in to the design of the buildings

Sir Terry Farrell is a big fan too: “I’ve always regarded (the Leeds campus) as one of the finest examples of the high era of modernism in England. Whereas so many university campuses of that time singularly failed and were drab and indeed anti-urbanist, this one, in its architecture, and its urbanism and quality of execution, is really quite outstanding.”

In the heart of the campus, Chancellor’s Court is a little green haven. Chamberlin, Powell and Bon likened it to the great Oxbridge quadrangles, but to my mind, it has more life, intimacy and interest. It’s beautifully landscaped with trees and plants dotted around the square and two huge rock features. It’s also now home to the university’s Sustainable Garden, an allotment-meets-forest style garden that has an array of herbs that you can pick and take home. And on the rooftop of the surrounding buildings, a garden was recently added, which is worth taking a look at if you can find your way up. According to the University website: “The garden features a mini-forest garden, wildflower meadows, an edible hedge, and a space to grow vegetables, salads and herbs. The aim is that the area will become a central hub on campus; a communal place to relax, as well as providing research opportunities.”

In the heart of the campus, Chancellor’s Court is a little green haven. Chamberlin, Powell and Bon likened it to the great Oxbridge quadrangles, but to my mind, it has more life, intimacy and interest. It’s beautifully landscaped with trees and plants dotted around the square and two huge rock features. It’s also now home to the university’s Sustainable Garden, an allotment-meets-forest style garden that has an array of herbs that you can pick and take home. And on the rooftop of the surrounding buildings, a garden was recently added, which is worth taking a look at if you can find your way up. According to the University website: “The garden features a mini-forest garden, wildflower meadows, an edible hedge, and a space to grow vegetables, salads and herbs. The aim is that the area will become a central hub on campus; a communal place to relax, as well as providing research opportunities.”

As we stroll uphill past the Edward Boyle Library, so we reach University Square and the oldest part of the university buildings in the shape of Beech Grove House and Beech Grove Terrace, both dating back to the 1790s. Finally, we reach Alfred Waterhouse’s wonderful Great Hall of 1894. This building represents the original point of the university and is now used for examinations, meetings and graduation ceremonies.

As we stroll uphill past the Edward Boyle Library, so we reach University Square and the oldest part of the university buildings in the shape of Beech Grove House and Beech Grove Terrace, both dating back to the 1790s. Finally, we reach Alfred Waterhouse’s wonderful Great Hall of 1894. This building represents the original point of the university and is now used for examinations, meetings and graduation ceremonies.

The Parkinson Building (1951) dominates Woodhouse Lane; and behind it is the magnificent (inside) Brotherton Library, a Beaux-Art building with art deco fittings, completed in 1936.

Then we headed left into the peaceful St George’s Fields (3.8 hectares, 9.3 acres), which served as Leeds’ general cemetery from 1835, when St John’s churchyard became full, until 1969. There is an elegant Greek Revival Gatehouse and non-denominational temple.

Then we headed left into the peaceful St George’s Fields (3.8 hectares, 9.3 acres), which served as Leeds’ general cemetery from 1835, when St John’s churchyard became full, until 1969. There is an elegant Greek Revival Gatehouse and non-denominational temple.

Clarendon Road, which we walked up next, used to be called Reservoir Street because of a reservoir there belonging to Leeds Corporation Waterworks. It was built in 1837 after cholera epidemics had swept Leeds in 1832. The North Lodge (c. 1850), a single-storey Gothic Cottage built alongside the reservoir, still survives behind the gardener’s cottage near the Victoria Monument.

At the top of Clarendon St is the Former Police Station, Fire Station and Library (1901). The Pevsner entry reads: “Dominated by its landmark lead-domed clock tower. In the extravagant free Italianate style of WH Thorp. Red brick, carved Bradford stone dressings including pickaxes and hoses on the keystone of the traceried central window.” WH Thorp was one of a core of Victorian & Edwardian Leeds’ architects who shaped the city in that period.

Woodhouse Moor (26 hectares, 64 acres) is really a park. It was once part of a much larger moor of the same name, including land now occupied by the University of Leeds. As a high position above Leeds, it has been a military rallying point, and Rampart Road (on the northeast side) is named after the ramparts which were once there. During the English Civil War, in 1642, Parliamentary forces led by Thomas Fairfax massed on Woodhouse Moor before taking Leeds from the royalists.

Acquired by the council in 1857 to improve public health in the city, Woodhouse Moor was often referred to as ‘the lungs of Leeds.’ The move to purchase the park was triggered by ‘encroachments’ upon the space; parts of the land were being parcelled off for development, and rumours circulated that a substantial section might be given over to the army as an encampment. A grassroots campaign in support of a public park gathered momentum, spurred by a sense of threat to the Moor’s heritage. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Moor was widely used for a variety of purposes, including sport (mainly cricket), musical concerts and political meetings.

By the beginning of the 20th century, there were extensive pleasure gardens and features such as the bandstand. During the Second World War, the Moor was given over to more utilitarian purposes including air raid shelters and allotments (some of which still exist, we pass them on our right). In 1937, four statues were moved from the centre of Leeds to the Moor to make way for road widening and a car park in Victoria Square – Wellington, Queen and Sir Henry Marsden, Robert Peel and Queen Victoria. She had briefly visited the moor in 1858 when she came to Leeds to open the Town Hall. The Moor was also one of the locations of the Festival of Britain in 1951 – a marquee exhibition and various displays were held there.

By the beginning of the 20th century, there were extensive pleasure gardens and features such as the bandstand. During the Second World War, the Moor was given over to more utilitarian purposes including air raid shelters and allotments (some of which still exist, we pass them on our right). In 1937, four statues were moved from the centre of Leeds to the Moor to make way for road widening and a car park in Victoria Square – Wellington, Queen and Sir Henry Marsden, Robert Peel and Queen Victoria. She had briefly visited the moor in 1858 when she came to Leeds to open the Town Hall. The Moor was also one of the locations of the Festival of Britain in 1951 – a marquee exhibition and various displays were held there.

The former Leeds Grammar School (1859) by EM Barry (he completed works on the Houses of Parliament undertaken by his father Sir Charles Barry, and built the Royal Opera House), now the University Business School, is in classic Gothic Revival style.

Moving through, we see the rather impressive Charles Thackrah Centre for Innovation. With a mission like that, I guess you have to look a little bit different, which it certainly does.

Clarendon Road was laid out by John Wilkinson in 1839. It was in-filled first by fashionable houses in spacious grounds, then by semi-detached houses and terraces. There are some attractive Victorian buildings, including No. 40 on the left, built for James Reffitt, a dyer; with an ornate tower, scrolled gable and a stone roundel carved with plants. At 71-75 on our right, now an NHS facility, is Fairbairn House (1841), a fine brick Italianate mansion, which was the home of Sir Peter Fairbairn, engineer, inventor, Mayor of Leeds and host to Queen Victoria & Prince Albert who stayed here when they came to open the Town Hall in 1858.

We turn right up the cobbled Kendal Lane, which had been an ancient pre-turnpike road that climbed the hill towards Great Woodhouse Moor, thence to Otley, Skipton and Kendal.

Behind the brick wall on our left is Claremont House (1772), from whose grounds Hanover Square was subsequently created. It was built for the Quaker merchant John Elam. It is now the headquarters of the Yorkshire Archaeological & Historical Society.

Moving along Kendal Lane, we spot Hanover Square down the hill to our left. First, though, we pass the impressive Denison Hall, which was built in 1786 (in just 101 days according to the blue plaque!!) as the home of the rich wool merchant John Wilkinson Denison; but for some reason he only lived there for a few years before it passed through a succession of owners. It proved a difficult house to sell, as, in the words of the Leeds Guide of 1806, it was “too large for a man of moderate fortune, and too near the town to be relished by a country gentleman”. By the end of the nineteenth century it was clear it was more suitable for institutional usage – being, in turn, a vicarage, nursing home, school, University Hall of residence and now – rather predictably – a suite of luxury apartments.

Moving along Kendal Lane, we spot Hanover Square down the hill to our left. First, though, we pass the impressive Denison Hall, which was built in 1786 (in just 101 days according to the blue plaque!!) as the home of the rich wool merchant John Wilkinson Denison; but for some reason he only lived there for a few years before it passed through a succession of owners. It proved a difficult house to sell, as, in the words of the Leeds Guide of 1806, it was “too large for a man of moderate fortune, and too near the town to be relished by a country gentleman”. By the end of the nineteenth century it was clear it was more suitable for institutional usage – being, in turn, a vicarage, nursing home, school, University Hall of residence and now – rather predictably – a suite of luxury apartments.

In 1823 the then owner, George Rawson, commissioned Watson and Pritchett to build Hanover Square in the extensive gardens of the house with the hall at the north side, with the intention of trying to bring harmony to what had been a chaotic, unplanned urban sprawl (and presumably to make some money). But, along with Woodhouse Square which we pass through shortly, it was never fully realised, as the present appearance shows, simply because the developers underestimated the reluctance of families to live so close to industry. John Atkinson commented on the failure to the Commons Committee on Smoke Prevention in 1845; “the body of smoke that comes across the side of the hill where I live is vastly large…there is a place called Woodhouse Square near me into which the smoke used to pour.” A large part of the mercantile community of Leeds had gone to reside in the more sanitary Headingley since 1851, according to a footnote in the 1861 census. It doesn’t stop it still being a very agreeable square today, but it is not in the grand Georgian style of, say, Queen Square which we saw earlier. Many of the properties are more modest houses built in the 1870s-90s. The garden square remained the property of Denison Hall until gifted to Leeds City Council, who made it public in 1958.

Woodhouse Square was laid out in the 1840s by John Atkinson of Little Woodhouse Hall. Ten houses were built along the south side, with Waverley House being built on the west. In 1839 Atkinson created Clarendon Road, with plots for villas on either side. The sloping central garden became a public park in 1905. During The Second World War, the park housed an emergency water tank, which is now a sunken garden, and the railings were replaced in 2006 as part of a regeneration project to breathe new life into the Square. On the east side is a statue of Sir Peter Fairbairn (knighted by none less than Queen Victoria on her famous visit).

Woodhouse Square was laid out in the 1840s by John Atkinson of Little Woodhouse Hall. Ten houses were built along the south side, with Waverley House being built on the west. In 1839 Atkinson created Clarendon Road, with plots for villas on either side. The sloping central garden became a public park in 1905. During The Second World War, the park housed an emergency water tank, which is now a sunken garden, and the railings were replaced in 2006 as part of a regeneration project to breathe new life into the Square. On the east side is a statue of Sir Peter Fairbairn (knighted by none less than Queen Victoria on her famous visit).

If you look right (south) just before the footbridge, you will see ‘Joseph’s Well’ (1888-1904). Up until the 1840s, the clothing industry was pretty much a cottage industry. John Barran changed all this. In 1851, the sewing machine arrived in Britain from America and he immediately adopted it, opening his first factory in Boar Lane thus creating a new industry. Subsequently, he invented a machine that could cut many layers of cloth to an exact measurement in one go.

The building that you see here was his third cloth-cutting factory, and at its peak, this was the largest clothing factory in the world employing some 3,000 people. In the 1980s it was converted into serviced office accommodation.

Then, we crossed back over the ring road of misery across a very unexceptional bridge, to be greeted by one of the most scrumptious fabulous buildings in Leeds, the old Leeds General Infirmary (1869), designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott.

Then, we crossed back over the ring road of misery across a very unexceptional bridge, to be greeted by one of the most scrumptious fabulous buildings in Leeds, the old Leeds General Infirmary (1869), designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott.

Before drawing up the plans, Gilbert Scott and the Infirmary’s Chief Physician, Dr Charles Chadwick, had visited many of the great contemporary hospitals of Europe. They were particularly impressed by hospitals based on the pavilion plan recommended by Florence Nightingale and adopted this for the new Infirmary. It featured the latest innovations, with plentiful baths and lavatories throughout. And if you find your walking companion exclaiming “It reminds me rather of St Pancras station!” well there is a reason. The hospital was being constructed just at the time of the competition for London’s St Pancras Station, which of course Gilbert Scott eventually won.

Next, we turned right down Oxford Place. First up on our right is the Britannia Buildings in Gothic Revival style (1860s), with a rather wonderful ornate stone arched entrance. Then the Oxford Place Methodist Church (1890s), in what Pevsner described as ‘Baroque taste with gusto’. With its ‘red pressed brick with stripy Morley Moor sandstone dressings’, it is a very agreeable building, and it’s unnerving to think that it was close to being demolished in the 1950s to make way for new law courts. How our thinking on Victorian statement buildings has changed for the better. It’s also a reminder of how successful and important the Methodist movement was in the 19th century, reaching out to folk in cities. The Chapel attracted large congregations each Sunday evening – as many as 4,000 people – and the mission work reached out into the poor areas close to the city centre.

We turned right along Westgate to catch a glimpse of the rather impressive post-modern Magistrate’s Court (1994) on the corner of Park St. In Leeds, the growth of the financial and business services sector from the mid-1980s onwards resulted in a boom in office developments in the city centre. Many of the buildings constructed at this time are in a style dubbed the ‘Leeds Look’, which is typified by the use of dark red brickwork and steeply pitched grey slate roofs, intended to derive from Leeds’ Victorian heritage.

We turned right along Westgate to catch a glimpse of the rather impressive post-modern Magistrate’s Court (1994) on the corner of Park St. In Leeds, the growth of the financial and business services sector from the mid-1980s onwards resulted in a boom in office developments in the city centre. Many of the buildings constructed at this time are in a style dubbed the ‘Leeds Look’, which is typified by the use of dark red brickwork and steeply pitched grey slate roofs, intended to derive from Leeds’ Victorian heritage.

Dr Kevin Grady, Director of the Leeds Civic Trust, described the Leeds Look as “an interim response in the 1980s for architecture that had a human scale and was pleasing on the eye following some of the mistakes of the 1960s and 70s.” The style has suffered some criticism, with architectural critic Ken Powell saying that “the style has been imposed with monotonous thoroughness and a marked dearth of imagination” and others describing it as a “bland reinterpretation of former warehouse style”. But the Magistrate’s Court seems to be an exception to this. It is visually interesting, eccentric even, and is much better than the other buildings in this style.

Park Square was laid out in 1788, with houses at the time that were regarded at the time as ‘not the equal of Park Place’ (it would seem that Monopoly thinking has always been alive and well…). In the nineteenth-century, the houses steadily became more used for offices and warehouses. It is the best piece of green space in the city centre, so pause and enjoy it.

On the south side is St Paul’s House, built in 1878 by Thomas Ambler in an ornate Hispano-Moorish style as a warehouse and cloth cutting works for Sir John Barran (his second), with ‘truly Mohammedan cresting’ (Pevsner). The building was extensively altered and restored in 1976 with a wholly new interior. The minarets, originally terra cotta, are now fibreglass reproductions.

On the south side is St Paul’s House, built in 1878 by Thomas Ambler in an ornate Hispano-Moorish style as a warehouse and cloth cutting works for Sir John Barran (his second), with ‘truly Mohammedan cresting’ (Pevsner). The building was extensively altered and restored in 1976 with a wholly new interior. The minarets, originally terra cotta, are now fibreglass reproductions.

York Place has lots of buildings of character. 30 York Place (just on your right as you come out of the passageway), the former ‘Hepper & Sons’ Horse & Carriage Repository’; 6-8 York Place is an interesting terra cotta brick building. And No. 1 is a fine building, previously a warehouse.

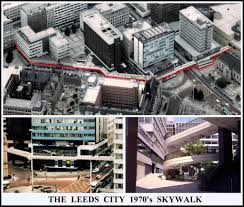

Grade II listed Bank House at the junction with King St is an architecturally adventurous example of the Bank of England’s 1960s building program, designed by BDP in 1969 as an inverted ziggurat in grey granite. What appears to be balconies on the first floor are actually remnants of the 1960s plan to connect the whole city via a network of elevated skywalks. These skywalks would allow pedestrians to float high above the chaos of the cars below as they made their way unencumbered about the city.

Grade II listed Bank House at the junction with King St is an architecturally adventurous example of the Bank of England’s 1960s building program, designed by BDP in 1969 as an inverted ziggurat in grey granite. What appears to be balconies on the first floor are actually remnants of the 1960s plan to connect the whole city via a network of elevated skywalks. These skywalks would allow pedestrians to float high above the chaos of the cars below as they made their way unencumbered about the city.

A section of this network was created in the 1970s; and new buildings constructed at this time had walkways built in for eventual connection to the ‘grid’. However, the success of the scheme was short lived and the walkways on Bank House were never used. Now they sit as a reminder of the ambitious, but ultimately misguided, schemes of the city planners of the 1960s and 70s to separate pedestrians from motorists (letting pedestrians make all the extra effort).

A section of this network was created in the 1970s; and new buildings constructed at this time had walkways built in for eventual connection to the ‘grid’. However, the success of the scheme was short lived and the walkways on Bank House were never used. Now they sit as a reminder of the ambitious, but ultimately misguided, schemes of the city planners of the 1960s and 70s to separate pedestrians from motorists (letting pedestrians make all the extra effort).

Just on our right at this point is the sumptuous Hotel Metropole (1897) in what Pevsner calls ‘undisciplined French Loire taste’. Inside, giant columns and a bronze-panelled staircase evoke the extravagance of late Victorian Leeds.

Then there are two rather fun buildings as you enter Quebec St – on the left is the Cloth Hall Court (1893) and on the right the former Leeds & County Liberal Club (1890) – now Quebec’s Hotel – with art nouveau details and a splendid interior, including a grand oak staircase with ornate balustrades of finely carved oak and lion finials, lit by five tall stained-glass windows which illustrate the coat of arms of five Yorkshire towns. At the time of construction, the Liberal Party dominated the administration of Leeds and the party wished to have a lavish political club that reflected their standing in the city. Under the stewardship of Edward Baines, the Leeds Mercury had become one of the most important props of the Liberal Party.

City Square was laid out from 1893 in grand style to celebrate the granting of city status. The Victorian layout of the square was swept away by the traffic engineers in the 1960s but remodelled by John Thorp in 2002.

The Old Post Office was built by Sir Henry Tanner in 1896. It was Leeds’ largest post office, and also served as the city’s telephone exchange. Between the 1960s and 1995, the north side of the square was home to a new Norwich Union building and another office block with an adjoining skyway. These buildings were voted the ‘ugliest buildings’ in the UK, and maybe that was one factor in their demolition in the 1990s.

So, the building that replaced them, No. 1 City Square (1998) didn’t have too high a hurdle to jump vs. what had gone before. It was the first building to eschew ‘the Leeds Look’ and produced a reasonable compromise between an art deco style and a functional building in black and white marble, bisected by a glazed elevator shaft under a roof canopy. The flight of sculpted seagulls that ascend the front of the building add a touch of fun and personality. Across the road lies another iconic piece of Leeds architecture, The Queens Hotel, dating back to the 1930s. It’s one of Leeds’ most famous landmarks and has played host to many famous guests including Laurel and Hardy in the 1930s.

Going back through the station, you get the best bit of it – the stylish 1938 Art Deco North Concourse with wide concrete arch crossbeams.

Going back through the station, you get the best bit of it – the stylish 1938 Art Deco North Concourse with wide concrete arch crossbeams.

Did you enjoy that?! Leeds has a mass of interesting architecture in so many different styles…Italian, Egyptian, Victorian Gothic (lots), Brutalist, Greek, Post-Modern, Hispano-Moorish, Art Nouveau, Art Deco … did I miss any?! And all the green space central Leeds has we saw!

THE ROUTE

- Exit the station on the south side next to Platform 17, the sign says ‘The Dark Arches’; exit S onto Leeds & Liverpool Canal and head W (right) along Wharf Approach

- Cross the bridge just beyond Wharf Candle House alongside Office Lock and head down Wharf Approach, then taking a path in front of you to reach Water Lane, where you turn right; bearing left where the road splits and then taking a left down Marshall St

- Just before you reach the ‘Egyptian’ building, take a left to the N of the Round Foundry Media offices into Saw Mill Yard. Exit back into Water Lane along Butcher St

- Retrace your steps back to the Office Lock bridge, turning right just before you reach it alongside the S side of the canal, briefly joining Canal Wharf then heading left around the corner of the BMB Group building over the canal; then turning R just after Fazenda to cross a bridge over the river and reach Little Neville St, which you head E along

- Cross Neville St, turn right then head down some steps to reach the riverbank, where you head E all the way to Leeds Bridge (if the entrance from Neville St is closed, go along Sovereign St instead).

- Cross the bridge, and take the first left down Dock St and the cross Centenary (foot) Bridge

- Head right up The Calls and then turn left through a metal gate and up some steps to St Peter’s Church (Leeds Minster) and then cross the road to Penny Pocket Park. Head back via High Court towards the Calls Landing building to rejoin the Calls.

- Head W along The Calls, turning right at Call Lane, then immediately left after the viaduct up Queen’s Court passage, to reach Briggate

- Turn right up Briggate, take a peek into Lambert’s Yard and then turn right into Hirst’s Yard passage opposite the wonderful Time Ball Buildings.

- At the end of the passage, take a left into Call Lane and then go around the back of the Corn Exchange; first Cloth Hall St, then Crown St, re-joining Call Lane where you turn right

- On reaching Kirkgate, cross at the pedestrian crossing and enter Kirkgate Market, heading straight through the front (Edwardian) part of the market to Harewood St, then take a left into Sidney St

- On reaching Vicar Lane, kink slightly to the right to head along the County Arcade, then cross Briggate to enter Thornton’s Arcade, turn left at the end of it, then cut back to Briggate along Queen’s Arcade

- Head N up Briggate, cross The Headrow and take a left through an arch into St John’s Churchyard, which you walk through to Merrion St, where you head left (W), crossing Albion St

- Take the next left into Dudley Way, right into St Anne’s St and left into Cookridge St

- Turn right along The Headrow to reach the Town Hall, where you turn right up Calverley St to reach Millennium Square

- Exit the square on the NE corner alongside the Civic Hall, going up Portland Crescent to reach Woodhouse Lane (optional) Cross the main road here and go down Queen Square to admire this wonderful Georgian square. Retrace your steps.Turn left (NW) up Woodhouse Lane, crossing the Inner Ring and then taking the 2

- Turn left (NW) up Woodhouse Lane, crossing the Inner Ring and then taking the 2nd left up Lodge St

- Turn left at the end down Vernon Rd, then right along the southern face of the E.C. Stoner Building to enter Chancellor’s Court. Exit at the far-right end up steps, head right following the path that twists up the slope to eventually reach the Great Hall

- Turn left here along University Rd, then right just before the School of Fine Art building to enter St George’s Fields, which you exit in the far-left corner into Clarendon Rd

- Turn right here, then left along Woodhouse Lane, taking the first left onto Woodhouse Moor, past the Victoria statue; head to the park’s centre point, then head SW with the tennis courts and allotments on your right, coming out on Moorland Rd