Farewells, welcome homes and new beginnings

Plymouth more than lives up to its moniker of ‘Britain’s Ocean City’, with estuaries, sea views, steep hills, naval defences and dockyards creating a walk of immense variety and interest.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 9.1 Kms (5.7 miles); or 11.8kms (7.4 miles) if you take the Devonport Park, Blockhouse Park & Central Park loop

- Height Gain: 70 metres

- Typical time: 2 1/2 hours, or 3 hours for longer route

- Start & Finish: Plymouth Station (PL4 6AB)

- Terrain: Mostly on hard surfaces, but a couple of short, steep climbs

| ‘Green Spaces’ | |

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | The Great Square, The Hoe, Elizabethan Gardens, Victoria Park, Patna Park, Devonport Park, Blockhouse Park, Central Park |

| Natural landscapes | Devil’s Point |

| Seafront | Plymouth Hoe |

| Stunning cityscape | Top of Smeaton’s Tower, Blockhouse Park |

| ‘Architectural Inspiration’ | |

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | St Andrew’s Church (15th C), Prysten House & Merchant’s House (15th C), Old Custom House (1586), The Royal Citadel (17th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Plymouth Synagogue (1762), Custom House (1820), Smeaton’s Tower (1759), Royal William Yard (1831), Devonport High School for Boys (1791) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | The Guildhall (1874), The Old Fish Market (1896), Elliot Terrace, Plymouth Hoe (mid-19th C) |

| Industrial Heritage | Wall of Industrial Memories, West Hoe |

| Modern (post-1918) | The Civic centre (1962), House of Fraser (1949), Pearl Assurance House (1952), The Baptist Church (1959), Roland Levinsky Building (2007, University of Plymouth) |

| ‘Fun stuff’ | |

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Quay 33, Boston Tea Party, Rock Salt Café, Column Bakehouse (Guildhall & King William Yard), The Park Pavilion Café |

| Quirky Shopping | The Plymouth City Market, The Barbican, 27 New St |

| Places to visit | The Barbican, The Lido, The National Marine Aquarium, Merchant’s House Museum, Elizabethan House Museum |

| Popular annual festivals & events | British Firework Championships (August), Plymouth Seafood Festival (September) |

City population: 264,200 (2016)

Ranking: 30th largest city in UK

Date of origin: 700 AD

‘Type’ of city: Maritime City

City status: Achieved in 1928 through merging with Devonport & East Stonehouse

Some famous inhabitants: Sir Francis Drake (navigator), Sir Joshua Reynolds (painter), Beryl Cook (painter), Michael Foot (politician), Sharron Davies (swimmer), Tom Daley (diver), Angela Rippon (journalist)

Notable city architects/planners: Sir John Rennie the Younger (1794-1874) – Royal William Yard, Sir Patrick Abercrombie (1879-1957) & Paton Watson (the 1944 Plan for Plymouth) HJW Stirling, city architect 1953-9

Number of Listed Buildings: Plymouth, 786, of which 24 are Grade I and 95 are Grade II*.

Films/TV series shot here: Tomorrow Never Dies (1997: Devenport Naval Base), Hornblower TV movies (various locations)

THE CONTEXT

Plymouth is defined by its ocean setting, situated between the Rivers Plym and Tamar in a beautiful natural harbour. The port and quaysides have always been at the centre of its livelihood, but for varying uses over the centuries; first, in the Middle Ages, as a port for wool and Dartmoor tin; then, in the 18th century onwards, as a base for the British navy during the period of the Empire; and in the last generation, as the dockyards have diminished, as a place to live and visit, with regenerated dockyards offering stylish apartment living and the café life, epitomised by the brilliantly restored Royal William Yard.

On closer inspection, the City of Plymouth is really three towns brought together in 1914 – Plymouth, Devonport and Stonehouse – with an eye at the time to achieving city status, which had been refused in 1911 on the grounds of there being an insufficient population in Plymouth alone – the requirement being for at least 300,000. This criterion was met through the merger of the three towns and city status was duly awarded in 1928. The walk goes through all three towns, and you will notice how distinctive they are.

Plymouth was profoundly altered by bombing in The Second World War, which destroyed the town centre and displaced many inhabitants. But out of the rubble emerged Britain’s first ‘planned’ town centre in an existing historic core, which English Heritage has described as one of the finest examples of post-war architecture in the UK (you may or may not agree!)

THE WALK

My first thought in coming out from the station was ‘Are we in the wrong city?’ For almost immediately the path is funnelled into an underpass beneath a roundabout and we could be – well anywhere – but most of all it is reminding me of a New Town (not that I have anything against new towns, it just wasn’t what I was expecting).

And this is the paradox of Plymouth: although it is full of history, forts and ancient monuments, the centre has been entirely re-built, courtesy of the Luftwaffe, who struck in a series of 59 raids in 1941 known as the ‘Plymouth Blitz’, halving the resident population as many fled to the fringes of Dartmoor to escape the bombing.

One positive that came out of all this destruction is that today Plymouth has the most post-war listed buildings of any British city outside London (incredible, but true). That’s why it holds a peculiar fascination for many architects who regard Plymouth as the finest example of post-war planning and architecture. Kevin McCloud of Grand Designs fame has described the city centre as “being really high quality and beautiful, it is carved stone, it is proper work. Its post-war buildings are very much of their time, representing a new wave of architecture around what was in the 1950s a brand new medium.” He has campaigned, alongside English Heritage, to have the modernist core of the city formally protected.

Hitler’s onslaught provided a blank canvas for Sir Patrick Abercrombie, the most eminent town planner of his day (and best known for his London ‘Abercrombie’ plan), and city engineer Paton Watson to build a brand new city out of a bombsite. The two men devised ‘A Plan for Plymouth’ in 1943, analysing all aspects of the city and the surrounding area (extending well beyond the city’s administrative boundary), exploring everything from history to geography, demographics to agriculture, before presenting a radical and all-encompassing vision of how a modern city should look and function. Based on the Beaux Arts ‘City Beautiful’ style and influenced by both Lutyens’ plan for New Delhi and the formation of Welwyn Garden City (compare the great avenue there, Parkway, with Armada Way here), the Plan proposed the almost complete removal of the old city centre with the formation of a grand north to south axis, connecting the railway station to the Hoe (the exact route we are taking). Crossing this axis, a grid of streets formed the main commercial, business and civic areas of the city. A grand east to west road (Royal Parade) separated the civic and commercial areas, with the whole area surrounded by a traffic-diverting ring road. Abercrombie declared the space “a vista for public enjoyment to be enriched by the landscape architect’s and gardener’s art.”

Abercrombie was driven by a vision of a city with which it is hard to disagree: “The city should be the focal point for the diffused rays of the many separate beams of life; it should be the centre of learning, of entertainment and of the market.” He felt that the Industrial Revolution had turned cities into “something more like a labour pool for the large industrial works – soulless and meaningless.” I leave it to you to judge how successful he was in Plymouth – for me there is a great sense of space, but almost a surfeit of space that creates a somewhat soulless feel about it, lacking the buzz that a city centre thrives on.

Armada Way, which has been spruced up again in recent years, is a pleasant rather than outstanding walk towards the Hoe, with a water feature flowing down the hill towards the sundial, bordered by grassy areas with shrubs, flower beds and a generous sprinkling of benches. The Piazza, half way down, was the scene of great celebrations when local lad Tom Daley, then just 15, returned to Plymouth as world diving champion in 2009. Everything in Plymouth seems to have a connection with water.

The most interesting stretch of the Way is the Civic Centre and The Great Square alongside it, which is on the National Register of Parks and Gardens. It was registered Grade II in 1999 and is one of the few 20th-century gardens listed. The aim of the Great Square was to evoke ‘dignity and frivolity’ in equal measure and to be ‘a civic amenity to be enjoyed by townspeople at all times’.

The most interesting stretch of the Way is the Civic Centre and The Great Square alongside it, which is on the National Register of Parks and Gardens. It was registered Grade II in 1999 and is one of the few 20th-century gardens listed. The aim of the Great Square was to evoke ‘dignity and frivolity’ in equal measure and to be ‘a civic amenity to be enjoyed by townspeople at all times’.

The Civic Centre (1962), in the words of English Heritage “embodies, as no other building, the hopes and aspirations of a newly confident City Council and serves as a striking testimony to the spirit which guided the reconstruction.” Inevitably it garners mixed reviews, but it is very much of its time and, in my view at least, is a minor gem. But its days as a civic centre are over. It was bought by Urban Splash in 2015 and awaits development. Urban Splash’s Chairman said of the site: “The Civic Centre has been unloved and is in need of tender loving care. It is in need of a big idea. We want to put it back at the heart of Plymouth with a mix of interesting uses. Watch this space.” We watch with interest!

We exited the Great Square to the NE heading, E on the pavement between the Royal Parade and Guildhall Square, with the Guildhall on our right.  The Guildhall (1874) was constructed in a French Gothic style and reflected the burgeoning civic pride in Plymouth at the time. Most of the complex was destroyed in the Blitz, however about one-third, including the tower was remodelled in the 1950s by HJW Stirling. The result is a rather curious Italianate-look, but I quite like it.

The Guildhall (1874) was constructed in a French Gothic style and reflected the burgeoning civic pride in Plymouth at the time. Most of the complex was destroyed in the Blitz, however about one-third, including the tower was remodelled in the 1950s by HJW Stirling. The result is a rather curious Italianate-look, but I quite like it.

The Royal Parade is the main commercial east-west axis of the new city centre plan, and many of the department stores and building societies are located along here.  The two we pass are the House of Fraser (1949) and then Pearl Assurance House (1952) a little further up. They set the parameters for the style of the new buildings, establishing features common to many of the buildings that were subsequently constructed – slim, elegant windows with metal frames painted white; shopfronts with fixed projecting canopies perforated with glass lens lights; white Portland stone facades (little used previously in Plymouth), rooted in classical ideas.

The two we pass are the House of Fraser (1949) and then Pearl Assurance House (1952) a little further up. They set the parameters for the style of the new buildings, establishing features common to many of the buildings that were subsequently constructed – slim, elegant windows with metal frames painted white; shopfronts with fixed projecting canopies perforated with glass lens lights; white Portland stone facades (little used previously in Plymouth), rooted in classical ideas.  Dotted around here and there are exquisite stone carvings and relief panels. Thomas Tait, who was the architect of the House of Fraser building (the first new building), was subsequently retained as a design consultant, and his influence was felt throughout the implementation of the plan.

Dotted around here and there are exquisite stone carvings and relief panels. Thomas Tait, who was the architect of the House of Fraser building (the first new building), was subsequently retained as a design consultant, and his influence was felt throughout the implementation of the plan.

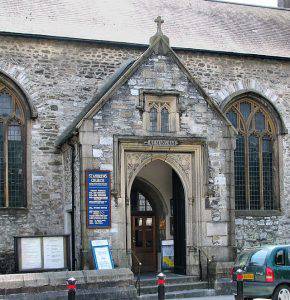

St Andrew’s Church was built in the mid to late 15th century, with its origins dating back to the 12th century. Sir George Gilbert Scott carried out a restoration in the 1870s (busy man).

In the blitz of 1941, the church was burnt out and left a roofless shell. Later a board bearing the word ‘RESURGAM’ (‘I will rise again’) appeared over the north door – the sign remains there to this day.  In 1943 rubble was cleared from the main body of the church, lawns were laid and areas planted as flower beds. A covered altar was erected at the east end and St Andrew’s became famous as the ‘Garden Church’ where, for six years, thousands worshipped at the open-air services. Princess Elizabeth visited the church in 1949 and unveiled a tablet to mark the beginning of the reconstruction. In 1957, rebuilt, redesigned internally but still essentially the church created in the 15th century, the church was re-consecrated.

In 1943 rubble was cleared from the main body of the church, lawns were laid and areas planted as flower beds. A covered altar was erected at the east end and St Andrew’s became famous as the ‘Garden Church’ where, for six years, thousands worshipped at the open-air services. Princess Elizabeth visited the church in 1949 and unveiled a tablet to mark the beginning of the reconstruction. In 1957, rebuilt, redesigned internally but still essentially the church created in the 15th century, the church was re-consecrated.

The Plymouth Synagogue (1762, Grade II*), the white building on our right as we head down Catherine St, is the oldest surviving synagogue built by Ashkenazi Jews in the English-speaking world. Sharman Kadish, the leading expert on Jewish buildings in Britain, believes that an unobtrusive location was chosen to avoid provoking the destructive riots that non-Anglican houses of worship often provoked in the eighteenth century. Nothing on the exterior distinguishes the building from the meeting houses of Nonconformist Protestants.

The Baptist Church (1958) that we come to next on our left replaced a church that had been destroyed in the Blitz. It was designed by Louis de Soissons, the architect and planner of Welwyn Garden City. Many interesting features include a decorated copper tower, a cobbled quadrangle, limed oak pews and pulpit, ‘tulip’ light fittings and a huge mural behind the altar. Legend has it that the forebears of this congregation “kindly entertained and courteously used” the Pilgrim Fathers in 1620 prior to their departure from the Barbican in the Mayflower.

The Baptist Church (1958) that we come to next on our left replaced a church that had been destroyed in the Blitz. It was designed by Louis de Soissons, the architect and planner of Welwyn Garden City. Many interesting features include a decorated copper tower, a cobbled quadrangle, limed oak pews and pulpit, ‘tulip’ light fittings and a huge mural behind the altar. Legend has it that the forebears of this congregation “kindly entertained and courteously used” the Pilgrim Fathers in 1620 prior to their departure from the Barbican in the Mayflower.

We slip through the car park just to the north of the church, then left up Finewell St to the Prysten House, a Grade I listed 15th-century merchant’s house, now the Greedy Goose restaurant.

Swinging round into St Andrew’s St and then right again along Higher Lane, Plymouth Magistrates Court (1979) is ahead of us, apparently cutting St Andrew St into two when it was built, much to the consternation of the residents.

The Merchants’ House, 33 St Andrew’s St was probably first built mid C15, remodelled late C16, and much remodelled in the C17. Its first recorded owner was William Parker, an Elizabethan privateer and merchant and Mayor of Plymouth at the start of the seventeenth century.

The Merchants’ House, 33 St Andrew’s St was probably first built mid C15, remodelled late C16, and much remodelled in the C17. Its first recorded owner was William Parker, an Elizabethan privateer and merchant and Mayor of Plymouth at the start of the seventeenth century.

Southside St twists round towards the quay, with an eclectic mix of historic building and rather tawdry shopfronts; we took the left down the interesting sounding ‘Citadel Ope’ onto The Parade.

The Book Cupboard that you come to immediately on the right is the Old Custom House (1586), with a blue plaque. It too started life as a Merchant’s house and was later used as the  customs house. There is an inscription “A 1623 K” over the right-hand doorway.

customs house. There is an inscription “A 1623 K” over the right-hand doorway.

The main Customs House was on the other side of The Parade. This custom house with its bonded warehouses was built in 1820. As we walked along Sutton Quay, we looked up at the old warehouses lining it — where cargoes like sugar and pearls from South America and spices from the East Indies were unloaded in the days when Plymouth was a thriving port.

Sutton Harbour is where it all began. In about 700AD Anglo Saxon settlers sailed here, making their first settlement on its shore. In the 16th century, it was used as the base for the fleet that gathered to face the Spanish Armada. In 1620 the Pilgrim Fathers sailed to America from the Mayflower Steps at the western end of the harbour.

Today this whole area is known as ‘The Barbican’. A Barbican is a fortified entrance. Here it refers to the waterside gateway of Plymouth’s long-gone medieval castle that stood on Lambhay Hill. The Barbican has a street pattern that Drake, Hawkins and Raleigh would recognise, apparently boasting the largest concentration of cobbled streets in England with over 100 listed buildings, many dating back to Tudor and Jacobean times.

Today this whole area is known as ‘The Barbican’. A Barbican is a fortified entrance. Here it refers to the waterside gateway of Plymouth’s long-gone medieval castle that stood on Lambhay Hill. The Barbican has a street pattern that Drake, Hawkins and Raleigh would recognise, apparently boasting the largest concentration of cobbled streets in England with over 100 listed buildings, many dating back to Tudor and Jacobean times.

The Old Fish Market (1896) (now the Edinburgh Woollen Mill) was a purpose-built harbour-side fish market. The building itself looked like a railway station. It was designed by James Inglis who left in 1895 to work for the Great Western Railway. The market remained in use until 1995, when a new fish market was opened on the opposite side of the harbour.

The Mayflower Steps. In 1890 a stone bearing the inscription ‘Mayflower 1620’ was set in the ground remembering the Pilgrim Fathers who left from here to continue their voyage to the New World, having sought temporary refuge in Plymouth. The slightly odd commemorative portico was added in 1934, with a small platform over the water with a brushed steel rail and a shelf with some nautical bronze artwork and historical information.

The Mayflower Steps. In 1890 a stone bearing the inscription ‘Mayflower 1620’ was set in the ground remembering the Pilgrim Fathers who left from here to continue their voyage to the New World, having sought temporary refuge in Plymouth. The slightly odd commemorative portico was added in 1934, with a small platform over the water with a brushed steel rail and a shelf with some nautical bronze artwork and historical information.

Just to the left of the Mayflower Steps is The Leviathan statue, nicknamed the ‘Barbican Prawn’. Installed as part of an Arts Council initiative, it is an amalgamation of various fish and marine life. It has a cormorant’s feet, a plesiosaurus’s tail, the fin of a John Dory, a lobster’s claws and the head of an angler fish.

New St, as is often the way with naming, turns out to be one of Plymouth’s oldest street and has several II*listed buildings (17,18, Elizabethan House Museum, 34 & 36) all of which were originally Merchants’ Houses. The delightful

New St, as is often the way with naming, turns out to be one of Plymouth’s oldest street and has several II*listed buildings (17,18, Elizabethan House Museum, 34 & 36) all of which were originally Merchants’ Houses. The delightful  Elizabethan Gardens at No. 34 is worth pausing in for a few moments.

Elizabethan Gardens at No. 34 is worth pausing in for a few moments.

Then we head back up onto the Hoe, past the elegant South African War memorial obelisk, unveiled in 1903.

Then we head back up onto the Hoe, past the elegant South African War memorial obelisk, unveiled in 1903.

Plymouth Hoe is the beating heart of Plymouth, with its stunning views of one of the most perfect natural harbours in the world. It’s a place where people have always gathered, from the music of the Edwardian era to the morale-boosting dances that Nancy Astor organised here during the dark days of the Second World War, to the city’s live band nights today.

One of the most famous gatherings was in 1967 when Sir Francis Chichester returned to Plymouth after completing the first single-handed Clipper Route circumnavigation of the world and was greeted by an estimated crowd of a million spectators on the Hoe, and every vantage point from Rame Head to Wembury. (Plymouth does outdoor spaces and welcoming people back very well!)

One of the most famous gatherings was in 1967 when Sir Francis Chichester returned to Plymouth after completing the first single-handed Clipper Route circumnavigation of the world and was greeted by an estimated crowd of a million spectators on the Hoe, and every vantage point from Rame Head to Wembury. (Plymouth does outdoor spaces and welcoming people back very well!)

Not surprisingly, when the annual British Firework Championships was inaugurated at the end of the 90s, Plymouth Sound became the favoured location as it provided a natural amphitheatre where large-scale pyrotechnics could be used safely and watched from a variety of points around the harbour and Sound.

A charming feature of the Hoe is that there is a lighthouse plonked in the middle of it, called Smeaton’s Tower. It was originally built in 1759 on the Eddystone Reef, a treacherous group of rocks that lie some 14 miles south-west of Plymouth but was taken down in the early 1880s when it was discovered that the sea was undermining the rock it was built on. Approximately two-thirds of the structure was moved stone by stone to its current position on the Hoe.

Smeaton was originally recommended to the task of building the lighthouse by the Royal Society. He modelled the shape of his lighthouse on that of an oak tree, using granite blocks; pioneering the use of hydraulic lime, a form of concrete that will set under water, and developing a technique of securing the granite blocks together using dovetail joints and marble dowels. Smeaton’s robust tower set the pattern for a new era of lighthouse construction that led to similar structures up and down the coast of Britain. Maybe that’s why it looks so familiar. The lighthouse was depicted on the British Penny for many years.

Everyone likes to get out on the water whenever they can…

Moving on around West Hoe, there is an interesting collection of replica naval vessels on the seawall along Grand Parade, called the Royal Navy Millennium Wall. Walking up the West Hoe Rd we enjoyed studying the ‘Wall of Industrial Memories’, a display of reclaimed signs illustrating the rich industrial heritage of the Millbay Docks area, including the Singer sign from a sail making machine, The Carruthers sign from a dock crane and an Armstrong sign on the former rail bridge at the docks’ mouth.

As we came into the Stonehouse area and Durnford St, we started to spot plaques set in the pavement commemorating the work of Sherlock Holmes: “Now Watson, the fair sex is your department,” and such-like. In 1882, Arthur Conan Doyle worked as a newly qualified physician here and lived at No. 1 Durnford St (towards the north end of the street, best seen on your way out).

At the southern end of Durnford St the road takes a wiggle and suddenly we are looking out to sea from Devil’s Point. It is a truly spectacular view, in many ways the ‘magic moment’ of the walk. This is the point where for centuries family and friends have waved goodbye to or welcomed home their loved ones.

Devil’s Point is a notable nature site, boasting unusual plant species on the low limestone cliffs and coastal grassland. It is also a European marine site of international conservation importance due to its wealth of marine and coastal wildlife.

A stairway linking Royal William Yard and Devil’s Point was officially opened to the public in 2013. The connection filled a gap in the South West Coast Path, bringing walkers around the Stonehouse peninsula for the first time. A grant was received towards the project from Natural England, who at the official opening of the steps described Plymouth as “one of our best-connected cities in terms of town and environment”. Couldn’t agree more.

Designed by Sir John Rennie and built between 1825 and 1831, the Royal William Yard is steeped in history. It was originally a Victualling Yard for the Royal Navy – and as we explored, we discovered an old bakery, a slaughterhouse, a spirits store, a brewhouse, a food store, clothing stores and much else besides. Today it is considered to be one of the most important groups of historic military buildings in Britain; it is also the largest collection of Grade 1 listed military buildings in Europe.

The Yard was de-commissioned in 1992 and subsequently passed into private hands. It was converted to an up-market mixed development by ‘Urban Splash’, who the Times newspaper described as ‘being in a class of its own when it comes to rescuing the great industrial landmarks of the past’. Urban Splash’s own website tells you much about their impact on the urban scene, and you will come across their work in several of our walks:

“Way back when, in the 1980s, when post-punk pop topped the charts, when New Romantics taught us to tuck our jumpers in our pants, when Thatcher and Scargill went to war over coal not dole, we were busy forgetting how great British cities had been and had no idea how great they might be again.

“In the beginning, there was no big plan, no strategy, no idea of what we were to become, just a wholehearted belief in cities, in design, in architecture and a desire to make things better. To make things the way we wanted them to be – different than they were before.

“In the early days, we worked with existing buildings that we fell in love with, buildings that had fallen apart and that we made better. When we ran out of buildings to convert we started to make our own. We made homes, we made offices and we made special spaces in between for people to be and do things that people do – in shops, bars restaurants, parks and even hotels.

“We started in Manchester and Liverpool but soon we were being encouraged to do things in other areas: Leeds (Saxton), Bradford, Plymouth, Bristol, Sheffield (Park Hill), Birmingham (The Rotunda and Fort Dunlop), Salford, all great cities that were thirsting for change.”

As we headed north from Royal William Yard, we crossed Stonehouse Creek. The lower reaches of the creek (immediately on our right) were filled in from the 1960s onwards and it is now a recreation ground and home to the Stonehouse Creek Social Club and Devonport High School Old Boys RFC. The upper reaches of the creek, now Victoria Park, were formerly known as the Deadlake. This area was filled in during the 1890s.

how it used to look in the 1950s…

On either side of the Creek were respectively the Royal Naval Hospital (southside, no longer in existence) and Stoke Military Hospital (1791, II*) (northside, now the Devonport High School for Boys), complete with landing quays so that patients could arrive by water. Stoke is an important early hospital design – four original square ward blocks segregating patients, linked by an arcaded and vaulted walk at the front. The construction workforce was made up of Napoleonic prisoners of war who were housed in prison ships in the estuary.

Victoria Park (6 hectares, 14.8 acres) was originally designed to be completed for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 1897, and named in her honour. However, the park wasn’t completed until 1905, four years after her death. The former park keeper’s lodge is in the centre of the park and is now a good café. Three underground shelters were constructed in it to protect the population during the Blitz.

Victoria Park (6 hectares, 14.8 acres) was originally designed to be completed for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in 1897, and named in her honour. However, the park wasn’t completed until 1905, four years after her death. The former park keeper’s lodge is in the centre of the park and is now a good café. Three underground shelters were constructed in it to protect the population during the Blitz.

Patna Park (2 hectares, 4.9 acres) has a rather novel-looking circular area that reminds one of the winner’s enclosure at a horseracing course but turns out to be a dog walking area (haven’t seen one like that before)

The name is interesting, several boats have been called Patna, hence perhaps the Plymouth link, including SS Patna, the name of the fictional ship in the novel Lord Jim by Joseph Conrad. Though never confirmed by the author, the ship is based on the real ship SS Jeddah. The fictional Patna used steam and sail in combination. About the right era too, the 1900s.

And so, we finish off with a sharp contrast that typifies the old and new Plymouth – a cobbled street (Staddon Terrace Lane) at the end of which you look straight over the Gyratory System in all its glory (not).

Devonport Park, Blockhouse Park & Central Park loop

This route adds 2.7kms (1.7 miles) to your walk, but pays back handsomely in terms of great views in many directions, and a chance to explore Devonport a bit.

Devonport Park (13 hectares, 33 acres) is a Victorian splendour, brought back to life in recent years by a Heritage Lottery Fund Grant. It is the oldest formal public park in Plymouth, opened in 1858. The first thing you notice as you go through the gates is the quaint Lower Lodge on your right, designed in the style of a Swiss lodge – symbolic of the new Park being intended as a place for healthy recreation and taking the air.

Apparently, this lodge had been boarded up until a few years ago but is now once again home to the park keeper. Living evidence of the renaissance of city parks, in this case, as in many, thanks to a £5.3 million grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund (co-funded with Plymouth City Council and Devonport Regeneration Community Partnership).

From around 1757 the land on which the park now is served as the ‘glacis’ – a part of the Devonport ‘Dock Line’ defences. These were open fields, kept free of development and providing no cover for an enemy. By the 1850s the ‘Dock Lines’ had little military value and Devonport was keen to respond to the national public park movement. Devonport Park was open by 1858 “for the purpose of healthful recreation by the public”.

To begin with, the planting and landscaping were restricted, but by the 1870s the Park, with its wonderful views, was “a source of daily pleasure to some hundreds of people”. There were improved walks, more trees & shrubs, with arbours and seats; plus the occasional rugby or cricket match. In 1894-5 more land was acquired and the larger and remodelled Park was re-launched as the ‘People’s Park’.

The park had a big role to play in WWII: underground air raid shelters were constructed to accommodate up to 600 people. Above ground, and in the event of a gas attack, a Cleansing and Decontamination Station was built; the nursery glasshouses were used to grow tomatoes; and areas of grassland were used for sheep pasture and haymaking; it was also a Barrage Balloon base; and in advance of the ‘D’-Day landings, parts of the Park were given over to American forces.

Blockhouse Park is one of the highest points in the city (70m) offering spectacular views of Dartmoor, Plymouth Sound and over the River Tamar to Bodmin Moor. The Mount Pleasant Redoubt sits at the highest point of the park and was originally built in the Napoleonic era. In the Second World War, it housed anti-aircraft guns to defend Devonport Dockyard which it looks down upon.

From here we also got a great view north of the neighbourhood areas outlined in the ‘Plan for Plymouth’. The Plan had proposed 13 neighbourhood units, built upon green fields and all named after local farms. It outlined a vision for each ‘Neighbourhood Unit’ to have access to the full range of facilities and services provided within 10 to 15 minutes walking distance from any part of it, each with suitable school provision and surrounded by a ‘Green Belt’. An impressive piece of planning.

The two neighbourhoods that we could see most clearly from here are Ham and Pennycross, and they have remained largely unaltered since they were built, testament to the fact that they have provided pleasant, positive living environments. Note the ‘triangular’ green in Ham, the centre of this community.

Central Park was created in 1931 for the outdoor recreation, health and well-being of the population. It was mainly formed from farmland, but its grand plan, formulated by one of the country’s leading landscape architect, Thomas Mawson, was only partially completed due to the economic constraints of the time. When war broke out in 1939, the character of the park changed considerably as it was hastily transformed into allotments to grow food, and space was set aside for air-raid shelters and a prisoner of war camp. In the post-war years, there was little capacity for restoring the park since re-building the devastated city centre and providing new housing took priority. It is only more recently that piecemeal improvements have taken place and what you find today is a useful, if slightly uninspiring, green space.

We finish off the walk by coming back in under the railway line and reaching the front of the station once again. Wow, what a walk!

THE ROUTE

- Leaving the station, turn left (SE) up Saltash Rd, and then take the underpass to Armada Way. Continue walking S until you reach Royal Parade

- Cross Royal Parade, past the pond on your left then double back to Guildhall Square

- Walk E along the pavement between Guildhall Sq and Royal Parade, turning right down Catherine St

- Cut left through a small car park just before the Baptist Church into Finewell St, turning left past the Greedy Goose and into St Andrew St

- Turn right here along Higher Lane and then first right through Sir John Hawkins Square to Palace St

- Turn right here, passing the Merchant’s House, heading down St Andrew St to join Notte St

- Turn left along Notte St, and then third right down the bending Southside St

- Take a left into the pedestrian Citadel Ope, and then right along The Parade and then follow the Quay round to the Mayflower Steps Memorial

- Cut up the steps by the Mayflower Centre, turning right into the tiny New St which you follow to its end

- Take steps immediately to your left where New St meets Citadel Rd E, crossing Lambhay Hill then doing a dog’s leg up to Hoe Rd

- Head SW across the Hoe, past the South African War Memorial to the Plymouth Naval Memorial and Smeaton’s Tower

- From the lighthouse, head W along the Hoe, then take the steps down to West Hoe Pier; follow the path around West Hoe hugging the coastline (you will see miniature boats on the sea wall). Follow the road north – first Great Western Rd, then West Hoe Rd, until you reach Mill Bay roundabout

- At the roundabout, head W along Millbay Rd, which becomes Caroline Place and then Barrack Place, until you reach Durnford St

- Turn left (S) into Durnford St and follow it all the way to its end, where it wiggles and becomes Admiralty Rd. Pass a car park on your right and take the metalled footpath around Devil’s Point; once around the head, take the path that heads up slightly, until it leads to a hole in the dockyard wall

- Descend the steep steps down to Royal William Yard and head along the quay, round the dock and out under the impressive arch and gates; then N up Cremyll St, swinging right back into Durnford St; continue heading N until you reach the roundabout; head W across Stonehouse Bridge, to the roundabout

- Turn right at the roundabout up King’s Rd, then right into the playing fields where the bicycle sign indicates; follow this bike path (Richmond Park) NE, to reach Mill Bridge

- Continue NE until the track finally swings round to the left; at this point take the exit from the park right, up some steps into Haystone Place

- Walk right down Haystone Place, left along North Rd W, left into Bayswater Rd, then right up Staddon Terrace Lane; coming out at the top, bearing right, then crossing over the dual carriageway via the footbridge back to the station.

Devonport Park, Blockhouse Park & Central Park loop

This route adds 2.7kms (1.7 miles) to your walk

- Immediately after this roundabout, take a half right along a track that rises slightly across a green space (Brickfields Triangle), which then comes back to meet the King’s Rd; follow alongside the left of this road until you come to the entrance to Devonport Park

- Head N through the park, and when you reach the bandstand head towards the NE exit. Head N up Victoria Place, across the railway line, turn right onto Alcester St, then along Pellew Place to reach Blockhouse Park, from where you get wonderful all-around views of the city

- From the high point, descend to Packington St, cross the Molesworth Rd and then take the first right into Ann’s Place. Turn left at Somerset Place and head for the Stoke Damerel Community College

- Take the path (cycleway) that runs E alongside the left of the college, and it eventually reaches the major Alma Rd; cross carefully, enter Central Park and head E until you reach the main N/S avenue

- Head S along this avenue and, as you reach the southern end of the park, head down the terrace furthest to the right (Wake St) until you reach the road. Turn right, and then left under the railway bridge and you are back at the start.

GREAT PIT STOPS

The Barbican area – just to the east of the walk, near the start, is full of cafés and restaurants and a great outlook on the marina. Quay 33 (33 Southside Street, PL1 2LE, Tel: 01752 229345) is especially popular for its good grub and great view.

Boston Tea Party, Jamaica House, 82 Vauxhall Street, Sutton Harbour, Plymouth, PL4 0EX (01752 267862, www.bostonteaparty.co.uk/our_cafes/plymouth.php)

Rock Salt Café Brasserie (31 Stonehouse St, PL1 3PE, Tel: 01752 225522, just N of Millbay Rd) is well described as a “pint-sized corner site run with bustling good cheer” that can offer either a quick sandwich or something more substantial.

Column Bakehouse The Factory Cooperage, Royal William Yard, Plymouth PL1 3QQ. Plymouth’s first and only social enterprise bakery.

The Park Pavilion Café, The Lodge Victoria Park, PL1 5NQ

QUIRKY SHOPPING

The Plymouth City Market (Cornwall St, PL1 1PS), W of Armada Way, is a Grade II listed building packed with a colourful array of stalls selling everything from pasties and picture frames to fresh flowers, fancy dress costumes and of course fresh fish off the boats.

The Barbican area is full of gift and art galleries. Several local artists have won global reputations, including the late Beryl Cook, and Robert Lenckiewicz.

27 New Street, PL1 2NB, is a group of old storehouses close to the Barbican waterfront in Plymouth occupied by one of the largest collection of antique traders in the South

PLACES TO VISIT

The Barbican: The Mayflower Steps, the spot close to the site on the Barbican from where it is believed the Pilgrim Fathers set sail for North America in 1620; and the Mayflower Museum, which explores Plymouth’s maritime history.

The Lido, just below the Hoe, is an art deco 1930s splendour recently restored and, if you’re feeling hardy, a chance for a dip. Open Jun-Sept. The view and setting are truly breathtaking.

The National Marine Aquarium (Rope Walk, PL4 0DX, 0844 893 7938) on the far side of the marina, the SW coast path runs by it) is the UK’s largest aquarium and has a fabulous location and views.

Merchant’s House Museum, 33 St Andrew St, Plymouth PL1 2AX (01752 304774). Not open in 2017, under reconstruction, check before visiting

Elizabethan House Museum, 32 New Street, The Barbican, Plymouth, PL1 2NA (01752 304774). Also closed at the moment for repairs. Check before visiting.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Read: Plymouth, Vision of a modern city, English Heritage (Historic England)

Tour: The Plymouth Gin Distillery in Southside St

7th March 2016 at 6:06 pm

Good to see Plymouth’s post-war reconstruction celebrated. If you’re interested in more on the Plan for Plymouth, I’ve written about it here:

https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/2013/01/15/a-plan-for-plymouth-our-first-great-welfare-state-city/

It’s off your walk but I’d also recommend looking at the pre-1914 council housing on Looe Street and How Street:

https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/2015/04/21/council-housing-in-plymouth-before-1914/

25th November 2016 at 12:27 pm

Thanks for that. I love the stuff you do.