Ratae – Ledecestre – Leicester – Les-tah!

INTRO

A walk through Leicester is a walk through architectural history – from the Victorian ‘statement’ buildings of the city centre, when Leicester was one of the wealthiest towns in Europe, via a Lutyens cenotaph, to the bold post-war buildings of the university, most notably Stirling’s Engineering building; and then an area of regenerated canal with 19th century warehouses and industrial buildings. There really is much more to Leicester than first meets the eye.

A detailed Ordnance Survey map of the walk can also be found at www.walkingworld.com , walk no. 7456

WALK DATA

Distance: 10kms (6 miles)

Typical time: 2.5 hrs

Height gain: 30 metres

Map: Ordnance Survey Explorer Map 233 Leicester & Hinckley

Start & finish: Highcross Shopping Centre (LE1 4AN). It’s also only a short walk from the railway station (LE2 0QB), joining the route at New Walk via De Montfort St.

Terrain: straightforward; sturdy footwear recommended

BEST FOR

| ‘Green Spaces’ | |

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Jubilee Square, Cathedral Gardens, Town Hall Square, Victoria Park, Welford Rd Cemetery, Nelson Mandela Park, Ruth Keene Herb Garden, Castle Gardens, The Rally, Abbey Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Soar, Grand Union Canal |

| Stunning cityscape | Welford Rd Cemetery, looking north; rooftop terrace bar at Hotel Maiyango |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1740) | The Guildhall (1390), Leicester Cathedral (11th C), The Turret Gateway (14th C), St Mary de Castro Church (12th C), Leicester Castle (11th C), Leicester Abbey (12th C), St Margaret’s Church (15th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | New Walk houses, Leicester Prison (1828) |

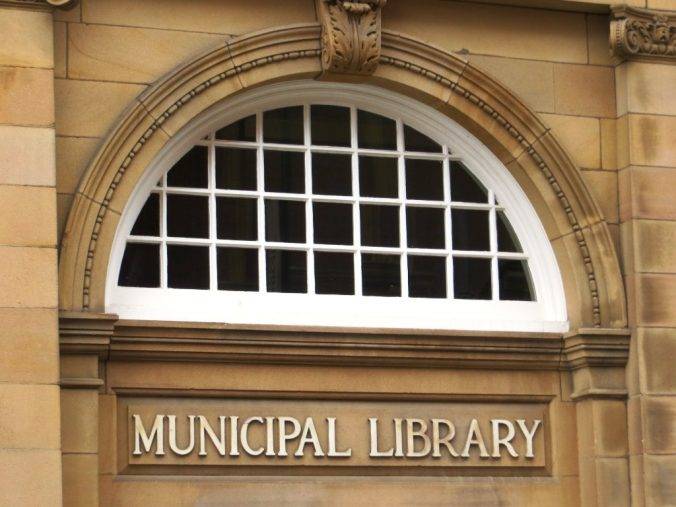

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Town Hall (1879), Municipal Library (1871), Fenwicks (1884), Portland Building (1890s) – and many others besides |

| Industrial Heritage | Hosiery factories (Gateway area), Leicester and Swannington Railway at The Rally , Frog Island Mills |

| Modern (post-1918) | Stirling Engineering Building (1963), Queen’s Building at De Montfort (1993), Curve Theatre (2008;not on route) |

| ‘Fun stuff’ | |

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | World Peace Café, Delilah Fine Foods, Vintage Tea Room, Shivalli |

| Quirky Shopping | The Lanes, Leicester Market |

| Places to visit | Guildhall, Cathedral, Richard III Visitor Centre, Jewry Hall Museum, New Walk Museum |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Riverside Festival (early June), Diwali Festival (early November) |

Urban population: 330,000 (2011 census)

Metropolitan population: 509,000 (2011 census)

Ranking: 13th largest city in the UK

City status: Leicester was re-granted city status in 1919. In 1925, it became a cathedral city again on the consecration of St Martin’s. It had lost city status in the 11th century during a time of struggle between the church and the aristocracy.

‘Type’ of city: ‘Workshop-driven’ manufacturing city

City walkability: (www.walkscore.com): 94/100, ‘Walker’s Paradise’

Some famous Leicester people: David Attenborough (naturalist), Richard Attenborough (actor), Kasabian (pop band), Engelbert Humperdinck (singer), Sue Townsend (author, Adrian Mole books), Joe Orton (playwright), Julian Barnes (author), Gary Lineker (footballer & TV pundit), Peter Shilton (footballer), Martin Johnson (rugby), Thomas Cook (travel pioneer), WG Hoskins (landscape historian and my personal inspiration), Alastair Campbell (journalist and political advisor); Richard III (buried here), Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester (founder of the English Parliament), Gok Wan (fashion stylist).

Notable city architects / planners: Konrad Smigielski (1960s planner) who re-shaped the city

Films/TV series shot here: Yamla Pagla Deewana 2 (2013), a Bollywood movie, was filmed at University of Leicester campus

CONTEXT

Leicester has not always had a good press. Even W.G. Hoskins, the famous historical geographer long associated with the county, starts his description in the Shell Guide: “Leicester is, at first sight, a totally uninteresting Midland city… It is indeed a desert of hundreds of acres of little red brick terrace houses put up in the last decades of the C19th; and estates put up in the 30s and after that more modern sprawl for miles around.”

But there is much more to Leicester than meets the eye. In reality, it is one of the country’s most historic cities, having been inhabited since Roman times. Under the Romans, it was named Ratae and was an important strategic outpost. When it was subsequently captured by the Danes it became one of five fortified towns important to the Danelaw, and it appeared in the Domesday Book as “Ledecestre”. It continued to grow throughout the Early Modern period as a market town; but it was during the industrial revolution that it really took off, becoming a leading producer of hosiery, textiles and footwear. Manufacturers such as N. Corah & Sons and the Co-operative Boot and Shoe Company were opening some of the largest manufacturing premises in Europe. During this period Leicester became one of Europe’s wealthiest cities.

Its lack of natural features is perhaps why Leicester has never been a contender for the crown of Britain’s ‘favourite’ city – more hills or a coastal location tend to add drama and, of course, it has neither of these. Also, it’s in the Midlands, somehow neither north nor south therefore not so easily pigeonholed, but easy to pass by I know, I live in the Midlands too). And it doesn’t have an ancient cathedral to define it.

But its lack of natural features had distinct advantages – there was nothing to constrain it other than the River Soar, so Leicester was able to expand to accommodate the rapid growth in population in the 19th century without the centre becoming over-crowded and unsanitary, as happened in neighbouring Nottingham.

Hoskins explains: “The fields which practically surrounded the ancient town had all been enclosed before the need for more building land had become desperate. There was almost unlimited space for Leicester to expand; and in 1845 the commissioners were able to report that the town ‘was spread over an unusual extent of ground in proportion to its population.” Many large gardens were still to be seen, even in the centre of town. The newer streets were wider than the average for manufacturing towns.

It was not until the 1960s that the structure of the city was to change fundamentally again. Konrad Smigielski was appointed City Planning Officer in 1962, one of the earliest such posts in the UK; he presided over the construction of the inner ring road in the late 60s and early 70s and the creation of the Haymarket shopping centre, which necessitated the destruction of a large chunk of old Leicester. This inner ring road severed in two much of the city’s fabric, as happened in so many cities in the UK during this period, as a result of plans drawn up under the guidelines of the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, which had identified that one of the major issues in post-war cities was traffic congestion.

In more recent years, thank heavens, these policies have gone into reverse, crystallising around the ‘Connecting Leicester’ programme launched in 2012. This is an ambitious programme which includes improving pedestrian and cycle links from the old town to New Walk and northwards to Abbey Park. The new Highcross, Jubilee Square, the re-vamped Lanes are all examples of this; as is the growing cohesion of the space between Highcross and the Curve, a buzzing, creative and attractive part of the city.

The City Mayor in 2012, Peter Soulsby, explained it thus: “Our priority is to create connections to provide a safe, family and pedestrian-friendly city centre. Connecting the different parts of the city centre and reducing the dominance of roads to create an attractive, environment for local people to enjoy their historic city.”

Today, Leicester has a real buzz about it and plenty of open spaces to enjoy. The Richard III bandwagon raised the profile of Leicester sharply for potential visitors, and the Richard III Visitor Centre and the king’s reinterment in the Cathedral gave a focus to this interest that should translate into more visitors.

But what sets Leicester apart for me is the sheer range and quality of architecture on show, fuelled by the city’s wealth and non-conformist drive in the 19th century and the big capital investments in its two universities post-war.

WALK

Our walk began in Highcross, which is that very rare beast, a shopping centre that is agreeable to walk through. Why? Some appealing architecture (the John Lewis building), open streets and some excellent quality materials used in the paving and street furniture. Plus some ping-pong tables if you fancy a quick game. And a cluster (what is the collective noun for restaurants, maybe a cook-ophany?!) of restaurants, admittedly mainly chains, but good ones.

Coming out of the shopping area we came onto St Nicholas Square and the new Jubilee Square pedestrian area. Like all pedestrianisation projects up and down the country, this involved an awful lot of moaning during its construction – too expensive, too slow, a permanent building site, poorly specified materials, insufficient delineation between pedestrianised and vehicular, loss of parking spaces etc. – but, as a mere visitor, it is a delight, part of Leicester’s continuing fight back against the killer embrace of the ring road which strangled the city back in the late 1960s and early 1970s and severed several medieval streets in the process.

But enough of my rant about the ring road scheme. As we took a left turn down Guildhall Lane, we were transported back 600 years and suddenly felt we were in a different city. Everything about the Guildhall looks reassuringly old – the timber-framed upper floors, the Georgian portico, the old cobbles out front.

It was originally constructed in 1390 and in the intervening years has been the ultimate architectural ‘jack of all trades’: it was the Town Hall until 1876, it was used for feasts, as a courtroom and for theatrical performances; it was the place where the ultimatum to the city was discussed during the English Civil War; it housed the third oldest public library in England, established in 1632; it was where Leicester’s first police force had its station, from 1836; it was a school; and since 1926, it has been a museum, briefly housing Richard III’s remains. Multi-purpose space or what?!

Alongside it is The Church of St Martin’s. It was consecrated as a cathedral in 1927, following the establishment of a new Diocese of Leicester in 1926, but its scale remains large church rather than cathedral. It has achieved worldwide fame recently as the place where Richard III was re-interred. The gardens on the south side have been the subject of a major re-design and are now a great place to sit on a sunny day and watch the world go by.

Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, and had been buried by the Grey Friars, a Franciscan Holy order, in their friary church close to where the cathedral is today. In 2012 his grave was re-discovered (by then, it was a council car park, giving rise to much ribald humour (“he put the KING in parKING”, surcharges for long stays etc. etc.)

If you want all the detail, drop into the Richard III Visitor centre which will take you through the whole excavation and complex identification process, led by the University of Leicester. Also, you can see his original grave.

We then moved on to the independent shopping quarter of the city; first up, the delightful Lanes, with a mix of independent shops, including gifts, fashion and much else besides.

Then on to the hurly-burly of Leicester Market, apparently the largest outdoor covered market in Europe; you would hardly have guessed that accolade would go to a city in the UK.

Cities and markets go together like toast and butter – and this one apparently, has been going strong since 1229, a little longer than your typical supermarket chain.

And what makes it great is what makes all markets great – a huge range of products from a huge range of countries sold by many different nationalities, by vendors who often do a good line in repartee – I defy you to name a fruit or a vegetable or a herb or spice that can’t be found somewhere here in the market!

The new indoor market, which houses the fish, meat and cheese traders, has won many awards. The Leicester Civic Society (civic societies generally take a lot to be impressed by a modern building) stated that it was “of uncompromising modern design that is nevertheless in scale and harmony with its important historic surroundings.”

We exited the market area through the entrance gateway, a metalwork arch with the produce of the market around its edges. Swinging right, we reached the Town Hall Square. Look across the square and you will see the splendid town hall on the far side, built in 1879 in the Queen Anne style, reflecting the high water mark of the city’s industrial wealth.

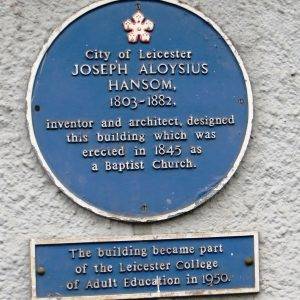

Just on from here we passed the Municipal Library dating back to 1871, and then the former Baptist Church, in Belvoir St, designed by Joseph Hansom and built in 1842. For generations, it has been known locally as ‘The Pork Pie Chapel’ because of its distinctive appearance. Made redundant as a Baptist church in 1939, it is now part of the College of Adult Education.

But doesn’t the name Hansom ring a bell? Yes indeed, it is the same Hanson who invented the Hansom Cab. He was a prolific architect who also designed the New Walk Museum, which was built in 1837 as a Nonconformist Proprietary School. With its distinctive ‘Italianate’ Tuscan pillars, it was built in conscious reaction to the Tudor Gothic style of Anglican schools of the same period. It re-opened in 1849 as a public museum, one of the first in the UK.

Non-conformism was a key driver of reform and improvement in Leicester in the 19th century, as it was in many British cities in the Midlands and the North. The religious census of 1851 revealed that total Nonconformist attendance was very close to that of Anglicans. And in most of the chief manufacturing areas, Nonconformists clearly outnumbered members of the Church of England.

Their tendency was towards reform, and a phrase developed during this period was ‘the non-conformist conscience’. Non-conformists often took the lead in the local politics of the city, usually liberal/Whig inclined. In Leicester it was the Unitarians, dominated by those of the Great Meeting in East Bond Street, who grew more and more influential, and after 1830 dominated Leicester politics.

Finally on our right, just before we reached New Walk, we saw the Fenwicks Building, resplendent in green, designed by Isaac Barradale, who was another of the city’s most notable Victorian architects. He was described by Pevsner as “arguably the finest architect of the Arts and Crafts movement in the country”.

New Walk begins with a 1970s monstrosity – the horseshoe-shaped council building – or did – the weekend after we did our walk it was demolished in a puff of smoke and a rash of road closures – a reminder that no city stands still and the life of a building can be as little as 40 years. Cracks had developed throughout the structure, causing the building to slowly “pull itself apart”. Most right-thinking people were delighted.

As you set off down New Walk, you might naturally suppose that this marvellous pedestrian-only way is one of the fruits of the ‘Connecting Leicester’ project recently set in motion. But doubts soon begin to creep in. How is it that in so much of the route is lined with elegant Georgian terraced houses? And at one point there is a charming Georgian square – de Montfort Square?

Further investigation reveals that New Walk is one of the oldest ‘purpose-built’ city pedestrian-only routes in the country, dating back to the 18th century.

There had not, in fact, been much reason for towns to set aside spaces for public use until some way into the nineteenth century, apart from those which remained from medieval times such as the market places and sites of fairs, or pieces of common land remaining from the enclosures. The case of Leicester, where in 1785 the Corporation resolved ‘to form a promenade for the recreation of the inhabitants ten yards wide from the North end of St Mary’s Field next to the town to the gate opposite the turnpike leading to London’, was almost unique. New Walk was laid out along the line of the old Roman Road, the ‘Via Devana’ (which ran from Colchester to Leicester), as a pleasant promenade at the expense of the Corporation which is still enjoyed to this day. Corporation far-sightedness indeed.

Being able to cross over the ring road without being interrupted by the traffic is a reminder of one of the more positive legacies of Konrad Smigielski, the City’s Town Planner. He put a halt to the plan which had involved cutting New Walk into two and helped ensure the whole of New Walk was granted Conservation Status in 1969 and completely re-furbished.

Soon after we crossed the ring road, we reached De Montfort Square. On the left is Bedrock Studios, where Kasabian made their first recording. Chris Edwards, the bassist, worked there as an engineer.

The land which is now Victoria Park (28 hectares, 69 acres) was originally part of the South Field of Leicester, which was enclosed in the early 19th century. Between 1806 and 1883 it was used as the town’s racecourse. In 1883 the races were transferred to the new Leicester Racecourse at Oadby, at which point it became a public park.

It’s a park that works brilliantly as an outdoor sports space; the day we went there were many families in the children’s play area, people getting fit in an outdoor gym zone, several games of 5 a-side football and scores of runners.

The park is also often used for open air concerts; one of the most memorable being Kasabian’s concert there in 2014, which they billed as their ‘Homecoming Show’, to a crowd of 50,000. Almost single-handedly Kasabian has given Leicester an ‘edge’ as a city, or ‘Lesta-h’ as they spelt it on the T-shirts they wore at the gig.

Half way along on your right, we looked across at the Lutyens War Memorial, built in 1923 to commemorate the dead of the First World War. The memorial, listed Grade I, stands at the top of an ornamental walkway with gates, also by Lutyens, opening onto University Road.

As we approached the far end of the park, so the shapes of the many University buildings came into view. Pride of place goes to Stirling’s Department of Engineering building, completed in 1963 and noted for its technological and geometric character. It is one of the iconic modernist buildings of the 1960s.

Incidentally, David Attenborough grew up on the campus, where his father was principal. Another impressive modern building, and the tallest on campus is the Attenborough Building named in his father’s honour. It has a distinctive paternoster (continuous) lift system, and offers the best views of Leicester from the top – but you will have to enrol as a student before you are allowed in!

Now, not everyone likes cemeteries. In fact my son Sam, who came on this walk with me, groaned as we pushed open the metal gate of the Welford Park Cemetery (12.2 hectares, 30 acres) alongside what used to be the Gardener’s Lodge – “not another cemetery, do we have to??” – but to those of you readers who, like me, are cemetery enthusiasts, this cemetery has much to offer – including a stunning view through the tombstones over the Welford Rd Rugby Stadium and the city beyond.

By the 1840s, as a consequence of a rapidly growing population, Leicester’s seven churchyards and seventeen chapel burial grounds were becoming full to overflowing and parts of the water supply were polluted with the run-off from graveyards. Leicester was not unusual in this respect, and by 1855 an Act had been passed closing town and city churchyards.

In 1843 Leicester’s large dissenting community led by William Biggs, a Unitarian, bought 17 acres of land to create a cemetery for dissenters. It soon became obvious that the cemetery would need to take Anglicans too and the Borough took over and obtained Parliamentary permission to establish the cemetery, which opened in 1849.

The chapels, one for Anglicans and one for other denominations, were completed in 1850 (although sadly demolished as unsafe just over 100 years later). Between 1855 and 1901 the cemetery was the only burial ground in Leicester and contains Victorian Leicester’s rich and poor alike.

Welford Road Cemetery predates Leicester’s public parks and is a classic Victorian garden cemetery intended as somewhere for the people of Leicester to enjoy the views over the Soar Valley, the fresh air and the flowers, shrubs and trees as well as to admire the memorials and pay respects to the departed. It was the third public municipal cemetery to be created in England, with only Birmingham and Plymouth pre-dating it (and all three designed by the same partnership of J. R. Hamilton and J. M. Medland).

One final thing to look out for in the cemetery is Thomas Cook’s grave (there is a location board of notable graves near the main entrance at the SW corner, close to the 1895 ornate entrance gates)

Cook’s idea to offer excursions apparently came to him whilst walking from Market Harborough to Leicester to attend a meeting of the Temperance Society. With the opening of the extended Midland Counties Railway, in 1841 he arranged to take 540 temperance campaigners from Leicester to a rally in Loughborough, eleven miles away. This was the first privately chartered excursion train to be advertised to the general public. This success led him to start his own business running rail excursions for pleasure, taking a percentage of the railway tickets. So this is where the ‘packaged’ holiday begun, and, in many ways, it is the same ‘packaged holiday’ concept that is still alive and kicking today, although generally now with more hedonism than temperance!

Walking back towards the centre, we passed the Old Fire Station, built in 1927 and now Grade 2 listed; alongside it in Lancaster Rd are the rather quaint firemen’s cottages built at the same time.

Our next slice of green space is Nelson Mandela Park, re-named in 1980 in honour of the former South African president. There is nothing very remarkable about the space itself, but on the left side of it is the famous (to rugby enthusiasts anyway) Welford Rd Rugby Stadium and to the right Leicester Prison, looking more like a mediaeval castle.

Rugby was a sport close to Nelson Mandela’s heart, and he often remarked how sport had the power to change the world. So perhaps, from that point of view, the park is well named.

The Leicester Tigers have played at this site since 1892. Rugby is very much the ‘regional sport’ of the Midlands, and Leicester Tigers have been its most famous team. Notable former players include England’s Rugby World Cup-winning captain Martin Johnson, Neil Back, Dean Richards and Austin Healey.

Nelson Mandela would probably also be able to associate very easily with the prison to the right, having been incarcerated himself for so many years on Robben Island. And prisoners peering out over the park might just afford themselves a wry smile on reading the inscription at its entrance: “There is no easy walk to freedom anywhere”.

For them, the fact that they are housed in a castle, designed by William Parsons and opened in 1828, is most probably a pain rather than a blessing. What do they care that the gatehouse, including the adjoining building to north and south and the perimeter wall, are Grade II listed? The poor conditions and lack of space in the jail have meant it has been the subject of many critical reports, but it stubbornly remains in use despite being very overcrowded.

One of its best-known prisoners was Brian Keenan. As the IRA’s quartermaster-general, he was the principal organiser of the bombing campaign that hit London in the mid-1970s and was jailed for 18 years in 1980. But he subsequently became key to the peace process, and he wrote from Leicester jail in 1982:

“It is not enough for Republicans to say, with reference to the Army [IRA], actions speak louder than words. We must never forsake action but the final war to win will be the savage war of peace. To those of us who have struggled for years in a purely military capacity, it must be obvious that if we do not provide honest, recognisable political leadership on the ground, we will lose that war for peace.”

Gerry Adams observed after Brian Keenan’s death in 2008: “There wouldn’t be a peace process if it wasn’t for Brian Keenan.” Perhaps Keenan had gained a little bit of inspiration from the park outside his window bearing the name of the world’s most famous prisoner and peacemaker.

Once past the hospital, we turn down Jarrom St and an area of closed-down hosiery and clothing factories, several of considerable architectural merit.

The Luke Turner & Co. elastic webbing factory on Deacon Street (1893) has an iron-frame construction, whilst the nearby Harrison and Hayes hosiery factory (1913) points the way to the more typical one and two storey buildings of the coming century. The external walls of this turn-of-the-century building are all of glazed‑brick in creamy yellow, green and brown.

As we walked up Gateway Street, the ‘young people with meaningful looks and laden with books’ count rose sharply and we soon found ourselves at the epicentre of Leicester’s second seat of further learning, De Montfort University. The university has approximately 30,000 students and staff – a reminder of just how important further education is to a city’s economics and cultural life.

De Montfort has several fine buildings, a recent stand-out building being the Queen’s Building by Short & Associates (1993). Its unique design means that the building has no need for heating as it controls the temperature through a series of vents.

At the top of Gateway Street is its oldest building, the Portland Building ; built in stages between 1896 and 1937, you can see how Leicester developed a traditional Jacobean style and then merged it into a sort of classical deco.

In the 1880s the local Leicester lad and hosiery industrialist AJ Mundella was often quoted in Hansard warning parliament about the advances of German education. A subsequent Act of 1889 allowed local authorities to levy for new colleges of technical instruction. An assortment of art schools and colleges were often absorbed into one Technical School which provided instruction to those employed in the local trades and formed close connections with the town’s industries. Just such an institution was the Technical & Arts Schools (now the Hawthorn Building), dating from 1896. These schools developed into what was to become De Montfort University in 1992.

Next, we headed back several centuries through the 14th century Turret Gateway and admired the exquisite Ruth Keene Herb Garden.

The St Mary de Castro church that we see next on our right dates back to the 12th century and was supposedly where Geoffrey Chaucer was married. The richest display of Norman architecture is to be found in the Chancel, documented by Pevsner as “a showpiece of late Norman sumptuousness”. This part of Leicester had been badly neglected until recently with its poor access from the city centre, but things are changing rapidly for the better, although you will probably encounter building works when you are there. One challenge remaining: the spire of the church had to be removed for safety reasons, but sufficient funds haven’t been raised yet to restore it!

Time maybe for a sit-down, and why not pause in the delightful Castle Gardens, a haven of tranquillity next to the river. The Castle Mound is the remains of Leicester’s first castle , built by order of William the Conqueror soon after The Battle of Hastings. It was placed in the south-west corner of the town to take advantage of the surviving Roman walls to the south and west.

At this point, the walk changes from city centre to river and canalside , with a stroll first alongside the River Soar and then the Grand Union Canal.

The ground just to the left as we reached the walkway that crosses the river is an area called ‘The Rally’. It was formerly the goods yard of the Leicester to Swannington Railway, built by Robert Stephenson in 1832 to bring coal from collieries in west Leicestershire to Leicester. It was one of England’s first railways.

Crossing the river into Soar Lane Island, the path soon reaches the start of ‘The Mile Straight’, a broad, straight and tree-lined ‘cut’ which was built as part of the 1890 Leicester flood prevention scheme. For centuries the river had flooded the surrounding low-lying land, which now for the first time could be properly developed.

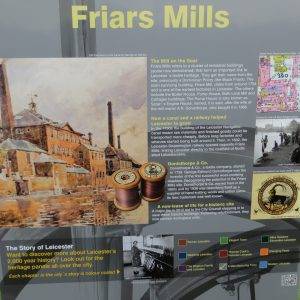

By the mid-twentieth century, there were several large mills in this area between this ‘cut’ and the river, and it became known as Frog Island. These mills manufactured clothing, machinery (particularly for the production of textiles) and materials demanded by the city’s hosiery trade, such as spun wool and dyes.

However, after the Second World War the area experienced a period of de-industrialisation and many of the businesses which occupied the island closed. Consequently, many of the large mills have become derelict and vandalised.

The area – recently re-named Leicester Waterside and stretching to the ring road – now forms an important part of the City’s wider Strategic Regeneration Area, designed to connect the city centre to the waterfront. It will include nearly 12,000 new homes and a new ‘urban square’, ‘a formal green space of contemporary design using high-quality materials, for people to dwell and enjoy’; and the restoration of several of the nineteenth century mills (including the listed St Leonard’s Works, Friars Mill and the Farben Works) has the potential to give the regenerated area real character and distinctiveness.

But this is still all a vision of the future, which you still have to screw your eyes up to envisage. Not so the glory of Abbey Park (23 hectares, 57 acres), which is a classic and delightful city park, opened in 1882. It was created from an area that had previously been described as “marshy ground in a poor district”. An early example then of urban regeneration. There is much to enjoy in the park, not least the miniature steam railway track, which has a strong and enthusiastic membership that meets and ‘steams’ every weekend.The Leicester Society of Model Engineers was founded in 1909, making it one of the oldest in the country; and they have been on this site since the early 1950s. A friendlier bunch of folk you would be hard pushed to find.

The park also contains the site of the 12th century Leicester Abbey, which is marked out with low stone walls; and the ruins of Cavendish House, used by Charles I after the siege of Leicester during the English Civil War in 1645; after he left, his soldiers set fire to it, leaving the house gutted. The charred stone window frame is still visible today. The abbey ruins contain a memorial to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who was buried in the grounds. He died while en route from York to London in 1530; a statue of him stands next to the Park’s Café. You didn’t expect this much history in Leicester, did you?

Finally, we crossed the canal by the Friday St on the final (and none too edifying part) leg of our journey. Just before reaching the ring road, though, if you haven’t quite got your fill of British architects by now, then you have a rather good final chance, as the route took us through St Margaret’s Church, which dates back to c. 1200. Most of the church was rebuilt in Perpendicular style in 1444, under William Alnwick, the Bishop of Lincoln. There was a subsequent Victorian restoration by George Gilbert Scott in 1860.

It had to happen eventually – and now it does – we need to navigate the ring road – there is an underpass here, dank and poorly maintained, but avoiding the traffic at least – what a salutary reminder at the end of our walk of just how important it is never to allow this type of planning vandalism to take place in our cities again – oh, and three cheers for the ‘Connecting Leicester’ Project.

THE ROUTE

- Starting from John Lewis Highcross, head SW down the pedestrian Bath House Lane, passing Wagamamas on your right; then up a flight of steps to Highcross St

- Turn left (S) into Highcross St and proceed to Nicholas Place (Jubilee Square) , skirting along its left side to Guildhall Lane

- Turn into Guildhall Lane, passing first the Guildhall then right down St mary’s West jus before the Cathedral; pass S through the Cathedral Gardens to St Martin’s, along which you head west

- Once in Hotel St, turn right and then take the first left along Market Place, past the covered market on your right

- Turn right at the Open Market and proceed S through the gates of the market, right into Horsefair St and then Town Hall Park. Cross to the SW corner of the park, then turn right down Bishop St

- At the end, turn left down Bowling Green St, then right along Belvoir St, until you reach New Walk, a pedestrian street running SE

- Take New Walk all the way until you reach Victoria Park, with a little detour into De Montfort Square (1.2Kms)

- Once in the park, turn right (SW), with the play & fitness area on your left and shortly the 5-a-side football on your right. Proceed, with the cenotaph a 100 metres or so to your right

- After 0.7kms turn right along the tarmac path to Mayor’s Walk and the University; you will see the Stirling Engineering building on your left; head down through the university to University Rd

- Cross and enter the Welford Rd Cemetery; take a left up to the high ground and then walk a circuit according to your interest back to this gate; then proceed NE up University Rd

- Turn left into Lancaster Rd, head NW under the railway and then walk through Nelson Mandela Park

- Cross both roads and head right (NW) up Infirmary Rd, with the hospital on your left

- Take a left into Jarrom St just after the public toilets

- Soon, turn right into Atkins St, then swing left into Henshaw St and then join Gateway St; turn right (N) and follow the road until it reaches a T-junction, the Newarke

- Turn right here, and then shortly left (N) up Castle View under the Turret Gateway.

- Head left at the St Mary de Castro church through the gate in the wall, into Castle Gardens. Head through the gardens W then N until you reach the footbridge over the River Soar, which you cross

- On the other side, turn right and then follow the river path, past the weir until you reach The Rally (about 0.6kms altogether), at which point you cross right over a bridge

- Crossing this bridge, you shortly join up with the Grand Union Canal ‘Mile Straight’ towpath, which you then follow (going under the road in both cases) until you reach Abbey Park

- As soon as you are in the park, take the left path (N) past the miniature railway; at the end of the park, turn left out of the gate along a path to a concrete bridge, which you cross

- Once over the bridge turn back right, following the river NE until you reach a large old bridge with several spans

- Cross this back into Abbey Park, and then head back to the park exit, with the lake on your immediate left

- Once out of the park, take Friday St (foot) bridge which immediately crosses the canal and heads into Friday St

- Take a left, then an immediate right into Watling St until you reach Canning Place

- Head right here and then walk slightly left through the churchyard of St Margaret, exiting at the far side into the underpass that enables you to cross the ring road

- At the far side, head down Church Gate, until you reach Butt Close Lane

- Take a right here, a left onto E Bond St, then shortly a right along Causeway Lane. You have made it back to the start point.

PITS STOPS

World Peace Café, 17 Guildhall Lane, LE1 5FQ . Part of a Buddhist Meditation Centre, it is run by volunteers from around the world.

Delilah Fine Foods, 4 St Martin’s, LE1 5DB (www.delilahfinefoods.co.uk) is a classy deli and restaurant which started life in Nottingham, where it’s rated as a ‘Local Gem’ by the good food Guide. recommended.

Vintage Tea Room and Crafts Leicester Indoor Market, Level C. A charming, no-nonsense tea room with a light and airy feel overlooking the market.

Shivalli , 21 Welford Rd, LE2 7AD, close to New Walk (0116 255 0137, www.shivallirestaurant.com). Indian vegetarian food of the highest quality. No frills, the lunchtime buffet is a bargain.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

The Lanes, just south of Highcross, are perfect for browsing, with lots of independent shops.

The Leicester Market, Indoor & Outdoor, is an institution not to be missed, at the south side of the Lanes in the Market Place. It is full of produce, meat & fish and also all sorts of other goods. Find out much more about it at www.leicestermarket.co.uk

PLACES TO VISIT

The Guildhall, Cathedral and Richard III Visitor Centre (Tel: 0300 300 0900, www.kriii.com). In August 1485 King Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth, and buried by the Grey Friars, a Franciscan Holy order, in their friary church. His grave now forms part of the Richard III Visitor Centre, and his remains have recently been re-interred in the Cathedral.

Leicester Museum in New Walk (Tel: 0116 225 4900) A charming museum, and if Egyptology or dinosaurs is your thing, a ‘must visit’ place. There are also often good exhibitions and a small, but interesting permanent collection of paintings and Picasso ceramics.

At Jewry Wall Museum (Tel: 0116 225 4971) you can discover the archaeology of Leicester’s past and find out about the people of Leicester from prehistoric times to the medieval period.

Leave a Reply