A ‘world city’ full of vitality and fabulous buildings

This walk takes you from the Georgian elegance of the ridge through the bustle of the city to the drama of Liverpool’s old docks, with amazing views and architecture throughout.

WALK DATA

- Distance: City ‘loop’ – 7.6 km (4.7 miles); ‘Parks’ loop – 7.7 km (4.8 miles)

- Typical time: City ‘loop’ – 2 hours; ‘Parks’ loop – 2 hours

- Height change: 45 metres

- Start & Finish: City ‘loop’ – Lime St Station (L1 1JD) ‘Parks’ loop – Hope St & Canning St (L1 9DZ)

- Terrain: mainly pavement; sturdy footwear recommended

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Roscoe Memorial Gardens, The Jubilee Quadrangle, Abercromby Square, Princes Park, Sefton Park, St James’s Cemetery, Concert Square, Chavasse Park, St Nicholas Church Gardens, St John’s Gardens |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Princes Park Lake, Sefton Park lakes, Upper & Lower Brooks, River Mersey; The Docks |

| Stunning cityscape | Liverpool Anglican Cathedral Tower |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | The site of Church of Our Lady and St Nicholas dates back to the 13th C, ‘Ye Hole in Ye Wall’ pub |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | The Wellington Rooms (1816), The Oratory (1829), Percy St (1830s), St Bride (1830), Rodney St (1790s-1810s), Scottish Presbyterian Church of Saint Andrew (1824), St Luke’s Church (1834), Bluecoat Chambers (1717), The Town Hall (1754) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Crown Hotel (1905), The Vines (1907), The Adelphi (1912), Victoria Hall (1892), Walker Engineering Buildings (1889), The Former Royal Infirmary (1890), Medical Institution (1837), The Philharmonic Hotel (1900), Liverpool Institute (1837), Liverpool School of Art and Design (1883), Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas (1870), Princes Rd Synagogue (1874), The Welsh Presbyterian Church (1867), Sefton Park Palm House (1896), Old Toxteth Library (1903), Port of Liverpool Building (1907), The Cunard Building (1917), The Royal Liver Building (1911), Oriel Chambers (1864), Bank of England Building (1848), Adelphi Bank (1890), The National Westminster Bank Building (1900), Royal Assurance Building (1893), Prudential Assurance Building (1856), The Municipal Buildings (1866), Pearl Assurance Building (1870s), Central Library and Walker’s Art Gallery (1860s), St George’s Hall (1854) |

| Industrial Heritage | The Rope Works, The Dock Traffic Office (1847), The Albert Dock (1846) |

| Modern (post-1918) | The John Lennon Art and Design Building (2008), Catholic Cathedral (1967), University Sports Centre (1966), Philharmonic Hall (1939), Liverpool (Anglican) Cathedral (1904-78), Aldham Robarts Learning Resource Centre (1993), The Queen Elizabeth Law Courts (1970s), Martins Bank (1932), The Royal Court Theatre (1938). |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | The Quarter, Bold St Café, Gelato Ice Cream, Ziferblat, Gourmet Coffee |

| Quirky Shopping | Bold St; The Bluecoat, School Lane; Lark Lane |

| Places to visit | Liverpool Cathedral & Tower, International Slavery Museum, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Tate Liverpool, Museum of Liverpool, Liverpool Town Hall, Walker Art Gallery |

| Popular annual festivals & events | International Music Festival (July, Sefton Park); International Beatleweek (Aug); Food & Drink Festival (Sept, Sefton Park); Liverpool Biennial (Contemporary Art, Summer 2018) |

City population: 484,600 (mid-2016 est.)

Urban population: 864,122 (mid-2016 est.)

City Ranking: 9th largest city in the UK

Date of origin: 1207

‘Type’ of city: Maritime City

City status: 1880

Ten Famous Liverpudlians: The Beatles (music), William Gladstone (prime minister), Cilla Black (singer), Jimmy Tarbuck (comedian), Steven Gerard and Wayne Rooney (footballers), Clive Barker (horror fiction writer), William Roscoe (philanthropist), George Stubbs (artist), Samuel Cunard (ship owner)

Notable city architects/planners: Jesse Hartley (1780 – 1860) – Civil Engineer and Superintendent of the Dock Estate, responsible for building most of the docks; Alfred Waterhouse (1830-1905) – former North Western Hotel, Victoria Building, Walker Engineering Laboratories, Royal Infirmary, Prudential Assurance Building, Former Pearl Assurance Building, 1 Devonshire Rd; Thomas Shelmerdine (1845–1921), City Surveyor of Liverpool – Kensington, Everton, Toxteth, Hornby, Sefton Park libraries; Central Fire Station, St John’s Gardens; Herbert Rowse (1887-1963) – India Buildings, Martins Bank, Mersey Tunnel, Philharmonic Hall; Graeme Shankland (1917–84), town planner – the post-war reconstruction of Liverpool.

Number of Listed Buildings: 2,500+, of which 27 are Grade I and 85 are II*. 5 buildings in the list are located at the Albert Dock and comprise the largest single collection of Grade I listed buildings anywhere in England. Liverpool has been described by Historic England as England’s finest Victorian city.

The historical significance and value of Liverpool’s architecture and port layout were recognised when, in 2004, UNESCO declared large parts of the city a World Heritage Site. In their words: “Liverpool is an outstanding example of a world mercantile port city, which represents the early development of global trading and cultural connections throughout the British Empire.”

Films shot here: Bullion Boys (1993 – docks), Shirley Valentine (1989), The 51st State (2002 – Anfield), Nowhere Boy (2009 – Hope St), Letter to Brezhnev (1985)

TV series shot here: Boys from the Blackstuff (1982), Liverpool 1 (1988-1999), Bread (1988-1991), The Liver Birds (1969-1979), Brookside (1982-2003), Scully (1984). The Hovis 2-minute ad showing 123 years of its history, all set in Liverpool.

Estimated % of accessible green space in the city (Eski): 16% (10th out of Top 10 cities). It should be noted, however, that The Historic England National Register of Historic Parks describes the Victorian parks in Liverpool as being ‘the most important in the country’. And we get to walk through them!

THE CONTEXT

Liverpool was founded in 1207, but remained a tiny settlement for several centuries, still only numbering about 500 people by the middle of the 16th-century. The settlement was centred around the castle at the foot of Castle St. Trade began to grow in the 17th-century, and the town was much fought over in the English Civil War, including an eighteen-day siege of the castle in 1644.

In 1699 the town was made a parish, the same year that its first slave ship, Liverpool Merchant, set sail for Africa. Since Roman times, the nearby city of Chester on the River Dee had been the region’s principal port on the Irish Sea. However, as the Dee began to silt up, maritime trade from Chester became increasingly difficult and shifted towards Liverpool on the neighbouring River Mersey. As trade from the West Indies surpassed that of Ireland and Europe, and as the River Dee continued to silt up, Liverpool began to grow with increasing rapidity. The first commercial wet dock was built in Liverpool in 1715.

By the start of the 19th century, a huge volume of trade was passing through Liverpool, and the construction of major buildings reflected this wealth. In 1830, the Liverpool to Manchester Railway was opened, the first in the country. The population continued to rise rapidly, especially during the 1840s when Irish migrants arrived by the hundreds of thousands as a result of the Great Famine.

As early as 1851 the city was described as “the New York of Europe”. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Liverpool was drawing immigrants from across Europe. This resulted in the construction of a diverse array of religious buildings in the city for the new ethnic and religious groups, many of which are still in use today. The Deutsche Kirche Liverpool, Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas, Gustav Adolf Church and Princes Road Synagogue were all established in the 1800s to serve Liverpool’s growing German, Greek, Nordic and Jewish communities.

During the Second World War, due to the strategic importance of the city, (the pivotal Battle of the Atlantic was planned, fought and won from here), the city suffered a blitz second only to London’s. The Luftwaffe made 80 air-raids on Merseyside, killing 2,500 people and causing damage to almost half the homes in the metropolitan area.

Significant rebuilding followed the war, including massive housing estates and the Seaforth Dock, the largest dock project in Britain. Much of the immediate reconstruction of the city centre has been deeply unpopular. The historic portions of the city that survived German bombing suffered extensive destruction during urban renewal.

In the 1960s, planning consultant Graeme Shankland advised Liverpool City Council on urban renewal. The resulting Liverpool City Centre Plan of 1965 declared two-thirds of the city’s buildings to be obsolete and proposed road-building on a vast scale, four-lane inner ring roads and multi-storeys for 36,000 cars (although to be fair it also recognised that Liverpool had outstanding Victorian architecture which must be preserved). Simon Jenkins famously compared Shankland to Bomber Harris. But the vision of modern amenities and services with clean people in cars must have seemed very attractive indeed given the slum conditions and bombed-out buildings. The city as we know it was saved by a lack of will and money, so not much of the plan came to pass.

In the 1960s, planning consultant Graeme Shankland advised Liverpool City Council on urban renewal. The resulting Liverpool City Centre Plan of 1965 declared two-thirds of the city’s buildings to be obsolete and proposed road-building on a vast scale, four-lane inner ring roads and multi-storeys for 36,000 cars (although to be fair it also recognised that Liverpool had outstanding Victorian architecture which must be preserved). Simon Jenkins famously compared Shankland to Bomber Harris. But the vision of modern amenities and services with clean people in cars must have seemed very attractive indeed given the slum conditions and bombed-out buildings. The city as we know it was saved by a lack of will and money, so not much of the plan came to pass.

Something else much more profound was also happening in Liverpool in the 1960s, the emergence of the cultural scene. In the 1960s Liverpool was the centre of the ‘Merseybeat’ sound, which became synonymous with The Beatles and fellow Liverpudlian rock bands. Alan Ginsberg famously declared in 1965 that “Liverpool is at the present moment the centre of the consciousness of the human universe”. This creativity has shaped the city to this day.

From the mid-1970s onwards, Liverpool’s docks and traditional manufacturing industries went into sharp decline due to the restructuring of shipping and industry, causing massive losses of jobs. The advent of containerisation meant that the city’s docks became largely obsolete.

The creation of the Merseyside Development Corporation (MDC) in 1981 was part of a new initiative that earmarked the regeneration of some 800 acres of Liverpool’s south docks, by using public sector investment to create infrastructure within an area that could then, in turn, be used to attract private sector investment. It placed a high priority on restoring those buildings that could be restored, including the iconic Albert Dock, and demolishing the rest. The success of this programme inspired the UNESCO World Heritage citation: Liverpool is the ‘supreme example of a commercial port at the time of Britain’s greatest global influence’.

Spearheaded by the multi-billion-pound Liverpool ONE development, regeneration has continued through to the start of the early 2010s. Some of the most significant redevelopment projects include new buildings in the Commercial District, the King’s Dock, Mann Island, the Lime Street Gateway, the Baltic Triangle, the RopeWalks, and the Edge Lane Gateway.

All projects could be eclipsed by the Liverpool Waters scheme, which if built will cost in the region of £5.5 billion and be one of the largest projects in the UK’s history. Liverpool Waters is a mixed-use development planned to contain one of Europe’s largest skyscraper clusters, in Vauxhall just north of the Three Graces. The project received outline planning permission in 2012, despite fierce opposition from such groups as UNESCO, which claimed that it would adversely affect Liverpool’s World Heritage status. On the plus side, the scheme proposes two parks and eighteen public squares.

To finish, on to the topography of this beautiful city. Ian Nairn, writing in the 1960s, summed up the shape of Liverpool so beautifully: “The city’s structure is tremendous…The Mersey runs North-South, and the docks stretch along it for seven miles, from Seaforth to Dingle. A mile inland, and parallel is a limestone ridge peppered with landmarks – the two cathedrals, the university, the football grounds at Goodison Park and Anfield. Between ridge and docks the city centre undulates downhill, never a simple-minded matter of boulevards, always with subtle double curves to the slope and something to close the view every few yards. The centre is humane and convenient to walk in, but never loses its scale.” This is the Liverpool that we can still experience on our walk, with much that has improved since then too.

THE WALK

Do try and arrive in Liverpool by train: for its history – opened in 1830, making it the oldest commercial train service in the world; for its beauty – two graceful Victorian engine sheds dating from the 1860s/70s; and its sense of place – being a terminus, it gives you the sense of arriving on the edge of the land mass with a great view west over the city towards the estuary, anchoring you immediately in the maritime history of the city. Ian Nairn sums up the distinctive spirit of the place beautifully: “It is a world city, far more so than London or Manchester. It doesn’t feel like anywhere else in Lancashire; comparisons always end up overseas – Dublin, or Boston, or Hamburg.”

Do try and arrive in Liverpool by train: for its history – opened in 1830, making it the oldest commercial train service in the world; for its beauty – two graceful Victorian engine sheds dating from the 1860s/70s; and its sense of place – being a terminus, it gives you the sense of arriving on the edge of the land mass with a great view west over the city towards the estuary, anchoring you immediately in the maritime history of the city. Ian Nairn sums up the distinctive spirit of the place beautifully: “It is a world city, far more so than London or Manchester. It doesn’t feel like anywhere else in Lancashire; comparisons always end up overseas – Dublin, or Boston, or Hamburg.”

The building on our right-hand side as we leave the station used to be the North Western Hotel (now student accommodation), designed by Alfred Waterhouse. He is the signature architect of the Victorian Gothic found in so many of the northern cities, and Liverpool is the canvas on which he designed most prolifically.

We resisted the strong temptation to make a beeline for the docks and the Three Graces straight away, and instead peeled off left along Lime St and then up Mount Pleasant to reach the sandstone ridge that affords such a fine outlook over the city and is home to its two cathedrals, the university and the Georgian Quarter.

It’s probably a bit early to start drinking, but there are two pubs we wanted to take a look at on our way up. First is the Crown Hotel, completed in 1905, a rich confection of brick, glass and copper externally, with sumptuous plasterwork and marble internally, a fine example of ‘art nouveau’. A few yards further along is The Vines, completed in 1907. It has a sumptuous interior of mahogany, beaten copper and rich plasterwork. Don’t miss the rear salon which was originally designed for billiards.

It’s probably a bit early to start drinking, but there are two pubs we wanted to take a look at on our way up. First is the Crown Hotel, completed in 1905, a rich confection of brick, glass and copper externally, with sumptuous plasterwork and marble internally, a fine example of ‘art nouveau’. A few yards further along is The Vines, completed in 1907. It has a sumptuous interior of mahogany, beaten copper and rich plasterwork. Don’t miss the rear salon which was originally designed for billiards.

In 1912, Arthur Towle acquired and rebuilt The Adelphi. Today’s building still reflects his care and ambition to make it one of the most luxurious hotels in Europe, serving as Liverpool’s arrival and departure point for passengers on the great liners. But it has seen better days, and was the subject of a famous ‘fly on the wall’ documentary in 1997 – it was the deputy manager who people most remember when during a row with the head chef he yelled: “Just cook will yer!” The phrase caught on, appearing on t-shirts and even as a novelty single.

Other buildings around the hotel, including the very ugly Mount Pleasant car park and the ABC cinema, are set for redevelopment under the Knowledge Quarter Gateway redevelopment. The council aims to build on the recent development of the eastern terrace of Lime Street and provide a positive impact on

Mount Pleasant, Brownlow Hill and Copperas Hill leading up to the ‘Knowledge Quarter Liverpool’, where we are headed. Much needed, as it still has a rather run down feeling about it.

Mount Pleasant, Brownlow Hill and Copperas Hill leading up to the ‘Knowledge Quarter Liverpool’, where we are headed. Much needed, as it still has a rather run down feeling about it.

The first bit of green space we come to is the Roscoe Memorial Gardens on our right, hemmed in on all sides by tall buildings. This was formally the burial ground of the old Renshaw Street Unitarian Chapel, which stood where the central hall is now located. William Roscoe (1735-1831) worshipped at the chapel and is buried here. He was one of the country’s leading slave abolitionists and an educationalist. One of his most notable achievements was the founding of an Institute for apprentice mechanics and engineers which, over nearly two centuries, has evolved into today’s thriving Liverpool John Moores University. The monument in the middle of the gardens, with its eight Doric columns, commemorates the original chapel.

The first bit of green space we come to is the Roscoe Memorial Gardens on our right, hemmed in on all sides by tall buildings. This was formally the burial ground of the old Renshaw Street Unitarian Chapel, which stood where the central hall is now located. William Roscoe (1735-1831) worshipped at the chapel and is buried here. He was one of the country’s leading slave abolitionists and an educationalist. One of his most notable achievements was the founding of an Institute for apprentice mechanics and engineers which, over nearly two centuries, has evolved into today’s thriving Liverpool John Moores University. The monument in the middle of the gardens, with its eight Doric columns, commemorates the original chapel.

The Wellington Rooms (1816) were originally used by high society for assemblies, dance balls and parties. The building reopened as the Liverpool Irish Centre in 1965, but has been derelict since 1997, and was subsequently placed on the National Heritage at Risk Register. Plans were announced in 2016 to turn the building into a Science and Technology Hub as part of the Knowledge Quarter plans. Fingers crossed. Behind it is The John Lennon Art and Design Building (2008).

The Wellington Rooms (1816) were originally used by high society for assemblies, dance balls and parties. The building reopened as the Liverpool Irish Centre in 1965, but has been derelict since 1997, and was subsequently placed on the National Heritage at Risk Register. Plans were announced in 2016 to turn the building into a Science and Technology Hub as part of the Knowledge Quarter plans. Fingers crossed. Behind it is The John Lennon Art and Design Building (2008).

During the Great Irish Famine (1845–1852) the Catholic population of Liverpool increased dramatically. About half a million Irish fled to England to escape the famine; many embarked from Liverpool to travel to North America while others remained in the city. The Catholic population has remained strong in the city into the twentieth century, and in 1930, Edwin Lutyens was commissioned to provide a design for a Catholic Cathedral that would be an appropriate response to the Giles Gilbert Scott-designed Neo-Gothic Anglican Cathedral then being built at the other end of Hope St.

Lutyens’ design was intended to create a massive structure that would have become the second-largest church in the world. Building work, based on Lutyens’ design, began in 1933, being paid for mostly by the contributions of working class Catholics. In 1941, the restrictions of World War II wartime and spiralling costs forced construction to stop. In 1956, work recommenced on the crypt, which was finished in 1958. Thereafter, Lutyens’ design for the Cathedral was considered too costly and was abandoned with only the crypt complete.

A competition to re-design the Cathedral was held in 1959. The requirement was first, for a congregation of 2,000 to be able to see the altar, in order that they could be more involved in the celebration of the Mass, and second, for the Lutyens crypt to be incorporated into the structure. Frederick Gibberd achieved these requirements by designing a circular building with the altar at its centre, and by transforming the roof of the crypt into an elevated platform, with the cathedral standing at one end. The new cathedral was consecrated in 1967.

It quickly became an iconic and generally loved landmark despite some structural defects that quickly became apparent (leaking roof!). Nicknames for the building include “Paddy’s Wigwam”, “The Pope’s Launching Pad” and “The Mersey Funnel”, and as soon as you see it you will understand why. We loved it – fun and awe-inspiring at the same time.

It quickly became an iconic and generally loved landmark despite some structural defects that quickly became apparent (leaking roof!). Nicknames for the building include “Paddy’s Wigwam”, “The Pope’s Launching Pad” and “The Mersey Funnel”, and as soon as you see it you will understand why. We loved it – fun and awe-inspiring at the same time.

One surprise – the steps we walk up, which seem so central to the impact created, were only completed in 2003 when a building that obstructed the stairway path was finally acquired and demolished.

One surprise – the steps we walk up, which seem so central to the impact created, were only completed in 2003 when a building that obstructed the stairway path was finally acquired and demolished.

We skirted around the west side of the cathedral and enjoyed a fabulous view down over the city towards the River Mersey. From the late 18th century, this ridge of high ground running north-south overlooking the crowded town was laid out with regular streets and developed as a favoured residential area away from the squalor. In the late 19th century the University College made its home here and is now a dominant presence.

We skirted around the west side of the cathedral and enjoyed a fabulous view down over the city towards the River Mersey. From the late 18th century, this ridge of high ground running north-south overlooking the crowded town was laid out with regular streets and developed as a favoured residential area away from the squalor. In the late 19th century the University College made its home here and is now a dominant presence.

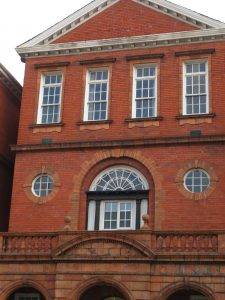

The university is where we are headed next, through an archway into the quadrangle of the gloriously neo-Gothic Victoria Hall (1892), designed by Alfred Waterhouse (of Manchester Town Hall and the Natural History Museum fame), built from a distinctive red pressed brick, with terracotta decorative dressings.

The university is where we are headed next, through an archway into the quadrangle of the gloriously neo-Gothic Victoria Hall (1892), designed by Alfred Waterhouse (of Manchester Town Hall and the Natural History Museum fame), built from a distinctive red pressed brick, with terracotta decorative dressings.

Originally housing administrative and teaching areas, it was the first purpose-built building for what was to become the University of Liverpool. It was also the inspiration for the term ‘red brick’ university, used to refer to a group of six civic British universities founded in the major industrial cities of England in the 19th and early 20th century (Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield and Bristol).

The term red brick was first coined by Edgar Allison Peers, a professor of Spanish at Liverpool, in his 1943 book ‘Redbrick University’. Red brick universities were distinguished by being non-collegiate institutions that admitted men without reference to religion or background and concentrated on imparting to their students ‘real-world’ skills, often linked to engineering. And, of course, a lot of the buildings that housed them were built in red bricks and a lot of those were designed by Alfred Waterhouse!

The Jubilee Quadrangle is an attractive piece of green space, re-landscaped to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s jubilee celebrations in 2012. The central green ring has 60 lights in the steps commemorating every year of the Queen’s reign. Paving stones around the green include etchings depicting significant local events that have taken place during her reign.

As we headed out of the NW corner of the Quad, we admired the detail of the Walker Engineering Buildings (1889), also by Waterhouse. And as we walk through, we pass two more of his buildings, the Whelan Building on our left and the Thompson Yates building on the right. This original core of the university is very much a Waterhouse creation, his most complete contribution to a university anywhere in the country.

The Former Royal Infirmary (1890) is also, of course, a Waterhouse building. He corresponded with Florence Nightingale and she succeeded in influencing some of his designs including the pavilion (Nightingale) wards, their height and number of beds designed to ensure sufficient daylight, ventilation and segregation. It was superseded in 1978 by the Royal Liverpool University Hospital in nearby Prescott St. After years of dereliction, the buildings were acquired in the 1990s by the university and sensitively refurbished, now being used as the School of Medicine for clinical skills teaching and examinations. This is a reminder of the key role that universities have come to play in restoring and utilising large Victorian institutional buildings (think also of the former North Western Hotel by the station, which has been modified as student accommodation; and hopefully the Wellington Rooms.)

The Former Royal Infirmary (1890) is also, of course, a Waterhouse building. He corresponded with Florence Nightingale and she succeeded in influencing some of his designs including the pavilion (Nightingale) wards, their height and number of beds designed to ensure sufficient daylight, ventilation and segregation. It was superseded in 1978 by the Royal Liverpool University Hospital in nearby Prescott St. After years of dereliction, the buildings were acquired in the 1990s by the university and sensitively refurbished, now being used as the School of Medicine for clinical skills teaching and examinations. This is a reminder of the key role that universities have come to play in restoring and utilising large Victorian institutional buildings (think also of the former North Western Hotel by the station, which has been modified as student accommodation; and hopefully the Wellington Rooms.)

Next, we headed south down Ashton St, a pleasant pedestrian and bicycle avenue with lots of green space and students mingling and taking exercise.

Next, we headed south down Ashton St, a pleasant pedestrian and bicycle avenue with lots of green space and students mingling and taking exercise.

Further down on the right is the University Sports Centre (1966) by Denys Lasdun (he of National Theatre fame, and a student of Maxwell Fry, who studied at the Liverpool Institute…). For those who enjoy a dose of brutalism…

Abercromby Square was laid out at the beginning of the 19th century, though most of the houses weren’t built and completed until the 1820s. Before this period the area was fields, marsh and a large pond, beyond the boundaries of the city centre. For a time, it became the most desirable place to live in Liverpool. Early inhabitants included several of the Liverpool dynasties and three of the prime movers in the creation of the Liverpool Manchester Railway.

Abercromby Square was laid out at the beginning of the 19th century, though most of the houses weren’t built and completed until the 1820s. Before this period the area was fields, marsh and a large pond, beyond the boundaries of the city centre. For a time, it became the most desirable place to live in Liverpool. Early inhabitants included several of the Liverpool dynasties and three of the prime movers in the creation of the Liverpool Manchester Railway.

On our way back to Hope St we passed the Oxford St Maternity Hospital (now student accommodation) in Cambridge Court, behind the Everyman Theatre.

As we passed, there was a cluster of tourists grouped around a guide talking earnestly, and it turned out that they were looking at a memorial to the birthplace of John Winston Lennon, born on 9th October 1940 in a second-floor ward of this hospital. He was named after his paternal grandfather and the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. His father was not present at the birth as he was away as a merchant seaman during World War II, probably typical of many births of that period.

As we passed, there was a cluster of tourists grouped around a guide talking earnestly, and it turned out that they were looking at a memorial to the birthplace of John Winston Lennon, born on 9th October 1940 in a second-floor ward of this hospital. He was named after his paternal grandfather and the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. His father was not present at the birth as he was away as a merchant seaman during World War II, probably typical of many births of that period.

The curved, 16-bayed Medical Institution (1837), in Greek revival style, makes good use of its position on the corner of Hope St. A medical library was first set up by a group of doctors in 1779, and this has been the use for this building throughout its life. Previously the site had been the Bowling Green Inn where William Roscoe was born in 1753.

Hope Street was voted as the best street in the UK and Ireland by The Academy of Urbanism a few years back. It has a great feeling about it, culture, pubs, interesting buildings, sculptures, historic spots, Beatlemania, a bit of everything.

The Philharmonic Hotel (1900) on our right is the most richly decorated of Liverpool’s Victorian pubs. It was built for the brewer Robert Cain, who aimed ‘to so beautify the public houses under his control that they would be an ornament to the town of his birth.’ The superb art nouveau gates lead to a sumptuous interior, divided by glass and mahogany partitions.

The Philharmonic Hotel (1900) on our right is the most richly decorated of Liverpool’s Victorian pubs. It was built for the brewer Robert Cain, who aimed ‘to so beautify the public houses under his control that they would be an ornament to the town of his birth.’ The superb art nouveau gates lead to a sumptuous interior, divided by glass and mahogany partitions.

Herbert J. Rowse was commissioned to design a new hall on the site of the previous Philharmonic Hall (1939) and he chose the Streamline Moderne style. Inside the entrance to the hall is a copper memorial to the musicians of the Titanic by J. A. Hodel.

Herbert J. Rowse was commissioned to design a new hall on the site of the previous Philharmonic Hall (1939) and he chose the Streamline Moderne style. Inside the entrance to the hall is a copper memorial to the musicians of the Titanic by J. A. Hodel.

The Hope Street ‘Suitcases’, installed by John King in 1998, ‘belong’ to many of Hope Street Quarter’s most illustrious names and organisations, including:

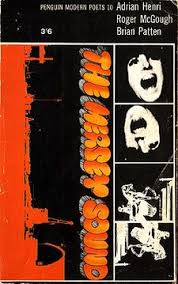

- Adrian Henri (1932-2000), who lived in Mount Street, lectured at the Liverpool College of Art and was one of the trio of poets who published The Mersey Sound in 1967

- Dr William Henry Duncan (1805-1863) Liverpool’s first Medical Officer of Health, who was largely responsible for the 1845 Sanitary Act, and lived in Rodney Street.

- George Harrison (1943-2001), musician and a member of The Beatles, who attended The Liverpool Institute.

- John Lennon (1940-1980), musician and member of The Beatles, who also attended Liverpool School of Art.

Looking down Mount St we spied the Liverpool Institute (1837) on our left, built originally as the Mechanics’ Institution. After that it became the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys Grammar School – alumni include Paul McCartney and George Harrison. It closed in the 1980s and now houses The Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, started by Sir Paul McCartney and Mark Featherstone-Witty. It was a meeting of two ideas: McCartney knew that the building which had housed his old school was becoming increasingly derelict and wished to find a productive use for it; Mark Featherstone-Witty had set up the Brit School in London and wanted to try his ideas on a bigger scale. It is now one of the United Kingdom’s leading institutions for the performing arts.

Looking down Mount St we spied the Liverpool Institute (1837) on our left, built originally as the Mechanics’ Institution. After that it became the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys Grammar School – alumni include Paul McCartney and George Harrison. It closed in the 1980s and now houses The Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, started by Sir Paul McCartney and Mark Featherstone-Witty. It was a meeting of two ideas: McCartney knew that the building which had housed his old school was becoming increasingly derelict and wished to find a productive use for it; Mark Featherstone-Witty had set up the Brit School in London and wanted to try his ideas on a bigger scale. It is now one of the United Kingdom’s leading institutions for the performing arts.

Liverpool School of Art and Design (1883), which fronts onto Hope St, is the oldest provincial art and design school. The extension along Hope Street, designed by Willink and Thicknesse, opened in 1910. The building is now part of the John Moores University. The university’s School of Art and Design moved out of the building to new premises at the Art and Design Academy in 2008, which we saw earlier.

Liverpool in the 1960s

The Liverpool College of Art was the hub of avant-garde activity in the late 1960s. The influential Arthur Ballard, whose pupils had included Stuart Sutcliffe and John Lennon, was joined at the college by a younger and more rebellious group of teachers – amongst them, Adrian Henri, Sam Walsh and Keith Arnatt. A community of artists, poets, writers and intellectuals gathered in the pubs, clubs and each other’s houses in the area surrounding the art school.

During his week amongst the city’s avant-garde in 1965, Ginsberg said that Liverpool reminded him of San Francisco – a comparison that most residents in the late 1960s would have laughed at. Never one to be half-hearted in his pronouncements, he declared that “Liverpool is at the present moment the centre of the consciousness of the human universe”. And this area we are in right now was its epicentre.

The Mersey Sound was the ‘bible’ of this group, an anthology of poems by Roger McGough, Brian Patten and Adrian Henri first published in 1967, when it launched the poets into ‘considerable acclaim and critical fame’. It went on to sell over 500,000 copies, becoming one of the best-selling poetry anthologies of all time. The poems are characterised by ‘accessibility, relevance and lack of pretension’. The Mersey poets’ manor was the art‑school. Their poems often name-checked the Anglican Cathedral – Adrian Henri imagined it dissolving in “a white-hot fireball”.

The Mersey Sound was the ‘bible’ of this group, an anthology of poems by Roger McGough, Brian Patten and Adrian Henri first published in 1967, when it launched the poets into ‘considerable acclaim and critical fame’. It went on to sell over 500,000 copies, becoming one of the best-selling poetry anthologies of all time. The poems are characterised by ‘accessibility, relevance and lack of pretension’. The Mersey poets’ manor was the art‑school. Their poems often name-checked the Anglican Cathedral – Adrian Henri imagined it dissolving in “a white-hot fireball”.

Brian Patten’s After Breakfast…

‘After breakfast,

Which is usually coffee and a view

Of teeming rain and the cathedral old and grey but

Smelling good with grass and ferns

I go out thinking of all those people who’ve come into this room…’

A personal favourite of this urban rambler is ‘Motorway’ by Roger McGough

The politicians,

(who are buying huge cars with hobnailed wheels the size of merry-go-rounds)

have a new plan. They are going to

put cobbles

in our eyesockets

and pebbles in our navels, and fill us up

with asphalt

and lay us side by side

so that we can take a more active part in the road

to destruction.

Remind you of Shankland’s road plan at all? We have a lot to thank these 60s visionaries for.

The area that we are now entering is called Canning and is almost entirely composed of residential Georgian style architecture, to compare with Edinburgh’s New Town or Clifton in Bristol. In 1800 the Liverpool Corporation Surveyor, John Foster, had prepared a gridiron plan for a large area of peat bog known as Mosslake Fields, which was to the east of Rodney Street. Situated on top of St James’s Mount away from the grime of the city centre, the area offered an opportunity to live in spacious comfort. With the city’s decline in the 20th century, the area grew unfashionable, and much of it became derelict. Areas along Upper Parliament St and Grove St and Myrtle St were demolished. The tide began to turn noticeably in the 1990s and the area is now much sought after once again, especially after the marked improvements to Hope St.

The area that we are now entering is called Canning and is almost entirely composed of residential Georgian style architecture, to compare with Edinburgh’s New Town or Clifton in Bristol. In 1800 the Liverpool Corporation Surveyor, John Foster, had prepared a gridiron plan for a large area of peat bog known as Mosslake Fields, which was to the east of Rodney Street. Situated on top of St James’s Mount away from the grime of the city centre, the area offered an opportunity to live in spacious comfort. With the city’s decline in the 20th century, the area grew unfashionable, and much of it became derelict. Areas along Upper Parliament St and Grove St and Myrtle St were demolished. The tide began to turn noticeably in the 1990s and the area is now much sought after once again, especially after the marked improvements to Hope St.

PARKS ‘LOOP’

This extra loop takes you through the Georgian quarter and Princes Park and Sefton Park – two of the finest parks in the country.

From the end of Hope St, we crossed onto Gambier Terrace (1830s-1870s), with the Anglican cathedral looming up large in front of us. The terrace has a nice slip of garden out the front which is well kept. John Lennon lived briefly at No. 3 in the early 60s.

From the end of Hope St, we crossed onto Gambier Terrace (1830s-1870s), with the Anglican cathedral looming up large in front of us. The terrace has a nice slip of garden out the front which is well kept. John Lennon lived briefly at No. 3 in the early 60s.

Canning St is one of the longest and best-preserved nineteenth-century residential streets in the area. And Percy St is widely regarded as the most distinguished street, most of the houses dating from the 1830s.  St Bride (1830) on the east side is the best surviving neoclassical church in the city, temple-like in appearance with its monumental portico of six unfluted Ionic columns across the west end. Today this is a church with a radical vision that provides a comforting home for all manner of groups and organisations – including the LGBT community, alcoholics, drug addicts, refugees, the homeless and the hungry. I like their motto: “Whatever you think of church, St Bride’s is doing it differently!”

St Bride (1830) on the east side is the best surviving neoclassical church in the city, temple-like in appearance with its monumental portico of six unfluted Ionic columns across the west end. Today this is a church with a radical vision that provides a comforting home for all manner of groups and organisations – including the LGBT community, alcoholics, drug addicts, refugees, the homeless and the hungry. I like their motto: “Whatever you think of church, St Bride’s is doing it differently!”

We head past the very charming Egerton St on our left, with modest two-storey houses dating from the 1840s. The street is best known for the famous Peter Kavanagh’s pub. Originally the Liver Inn. In 1897 young Irishman Peter Kavanagh got hold of it and gave it some serious love, turning it into the historically fascinating pub standing now. He commissioned the ornate wooden carvings, the Eric Robertson murals on the walls in the back and front rooms (1929) and the ornate tiling on the exterior. Moreover, he ran it for an astonishing 53 years and was truly a ‘renaissance landlord’ – on his afternoons off, he became a city councillor, benefactor, inventor (Hull tram car seats) and floral artist of note! Another Liverpool character.

We crossed into Princes Rd and on our left on the wall spotted the Florence Nightingale Memorial (1913). Although Nightingale is shown in traditional form as ‘the lady of the lamp’, this monument, paid for by public subscription, is really a memorial to her work as a public health promoter in Liverpool. She promoted not only proper training for nurses but also the notion that good nutrition and hygiene were necessary in the home and that this was best promoted through the work of visiting nurses. Nightingale worked on many initiatives with William Rathbone, including the building and organisation of the Liverpool Royal Infirmary that we passed earlier.

From very English architecture we are briefly hurled to the Mediterranean, first by way of the Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas (1870) built in the Neo-Byzantine style. The church was dedicated to St Nicholas, the patron saint to all seamen, as the money for the building was raised by the Greek ship owners who were based in Liverpool. It is an enlarged version of St Theodore’s church in Istanbul (now converted into the Vefa Kilise Mosque). The exterior is very ornate, featuring arches within arches, done in alternating bands of white stone and red brick. The interior (which we didn’t see) is apparently much plainer.

St Margaret’s C of E Church (1869) was paid for by Robert Horsfall, a local stockbroker and Anglo-Catholic. The architectural style of the church is Decorated neo Gothic. It has a very attractive vicarage from the same period too. This was the centre of Anglo-Catholicism in nineteenth century Liverpool and remains firmly rooted in the liberal catholic tradition of the Church of England to this day.

On the other side, The Kuumba Imani Millennium Centre is a multi-functional convention centre. Kuumba means to ‘always as much as we can, in the way we can, in order to leave our community more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it’. Imani means ‘to believe with all our heart in our people, our parents, our teachers, our leaders and the righteousness and victory of our struggle’.

Streatlam Tower next up on the left is now student accommodation. James Lord Bowes was a wealthy wool merchant, art collector and patron of the arts, author and authority on Japan and its art, and benefactor. In 1872, he commissioned Streatlam Tower, by architect George Ashdown Audsley, with whom he shared a passion for Japanese art, particularly ceramics. From the 1860s he had collected Japanese art works of all kinds, and in 1888 he was appointed the first foreign-born Japanese Consul in Great Britain. In 1890, in the grounds of Streatlam Tower, he opened to the public the first dedicated museum of Japanese art in the western world (sadly no longer there). Yet another Liverpool character.

Hurtling back to the Mediterranean again, next door is the Princes Rd Synagogue (1874); according to the Pevsner Guide ‘one of the finest examples of Orientalism in British synagogue architecture’. The style combines Gothic and Moorish elements. The interior is spectacular and it’s worth seeing if it’s open when you pass. Princes Road Synagogue came into existence when the Jewish community in Liverpool in the late 1860s decided to build itself a new synagogue, reflecting the status and wealth of the community. The synagogue stands in a cluster of houses of worship designed to advertise the wealth and status of the local captains of industry, a group that was remarkably ethnically diverse by the standards of Victorian England.

Swinging round the left where it becomes Princes Avenue, we see the Adult Deaf and Dumb Institute, 1887 by EH Banner, in an octagonal shape. An interesting building.

Princes Rd, Princes Avenue and the roads overlooking the parks were the places to build your large villa if you were a magnate or merchant, close to green spaces and away from the grime of the city and able to fraternise with other well-to-do folks. Princes Road, ‘a wide Victorian boulevard’ was completed in 1846, that rare thing in a British city a ‘planned route’. Princes Park was a pleasant stroll away, and a tram subsequently ran along its length. This became the ‘Park Lane of Liverpool’, the place to see and be seen.

The Welsh Presbyterian Church (1867) is another relic of those glory years, now sadly derelict. Because of its tall steeple, which for a time made it the tallest building in Liverpool, it was nicknamed the ‘Welsh Cathedral’, although it never had that status. Its scale, however, reflected the size and importance of the Welsh community in Liverpool. The ‘Welsh Streets’ nearby offer the most obvious historical link. The 16 streets – including Ringo Starr’s birthplace Madryn Street – were all given their names because they were built by Welsh workers at the end of the 19th century. With communities across the city, Welsh was the favoured language spoken in some areas and there were even Welsh language newspapers. It is estimated that by the end of the nineteenth century there were 50,000 Welsh living in the city. The Welsh Streets Resident Group has fought a long campaign to save these streets from demolition.

Upstairs, downstairs, it’s your choice…

Now, if you want to see some of these smart parkside houses, walk west along Devonshire Rd before heading into Prince’s Park. But if you want to see the Welsh Streets, veer right soon after you have entered Devonshire St and head west along South St. Never could there be two such contrasting streets so close to each other, but in a way, they tell the mercantile story of Liverpool in a nutshell – the wealth of the merchants on one hand and the working class on the other travelling to Liverpool supplying cheap labour for these merchants.

Devonshire Rd route: on the left, just after South St is No. 1 Devonshire Rd (now Mandela Court), a brick and stone Gothic House (1864), designed by Alfred Waterhouse and one of the houses intended to finance the park. It was first lived in by the family of GF Laster, a leading Liverpool Dock Engineer. On the north side, opposite the Sunnyside Road is Cavendish Gardens, an attractive three-storied terrace of eight houses dating back to the 1840s.

South St route: when we passed through, the area was teetering between dereliction and gentrification. Most of the houses were still boarded up, but there were signs here and there of renovation and some sensitive in-fills. Eventually, 300 homes will be refurbished – and the council estimates that 75% of existing homes will be retained rather than demolished. 9 Madryn St (near the top on the right) was the birthplace of Ringo Starr, and this fact was used extensively in the fight to save these streets from demolition.

Prince’s Park (45 hectares, 110 acres) was originally a private development (though open to the public), the creation of Richard Vaughan Yates, an iron merchant (I guess the railings would have been supplied by him then…), the cost of which was expected to be met through the development of grand Georgian-style housing around the park. It was principally designed by Joseph Paxton, the first major park he created. With its serpentine lake and a circular carriage drive, the park set a style which was to be widely emulated in Victorian urban development, most notably by Paxton himself on a larger scale at Birkenhead Park (itself a model for New York’s Central Park).

Sefton Park (95 hectares, 235 acres) was once within the boundaries of the 2,300-acre Royal Deer Park of Toxteth. The land was purchased by the Council in 1867 and, as with Prince’s Park, plots of land on the perimeter were sold for housing which helped in the funding of the layout of the park.

The park was designed by a French landscape architect Édouard André and Liverpool architect Lewis Hornblower, who won an open Council competition to design it. It was opened in 1872 by Prince Arthur who dedicated it “for the health and enjoyment of the townspeople”.

The Park design is based on circular and oval footpaths, framing the green spaces, with two natural watercourses (The Upper & Lower Brook) flowing into the man-made lake. Hornblower’s designs for the park lodges and entrances were elaborate structures and included follies, shelters and boathouses. The parkland itself included a deer park and the strong water theme was reflected by the presence of pools, waterfalls and stepping stones.

Extensive Lottery funding and volunteer effort have been put into the park since the millennium, including the restoration of the Sefton Park Palm House (1896), a Grade II* three-tier dome conservatory palm house designed and built by MacKenzie and Moncur of Edinburgh.

Extensive Lottery funding and volunteer effort have been put into the park since the millennium, including the restoration of the Sefton Park Palm House (1896), a Grade II* three-tier dome conservatory palm house designed and built by MacKenzie and Moncur of Edinburgh.

Exiting the park on the NE side, we passed the obelisk (1909) through gates by T Shelmerdine, Corporation Surveyor. To the left, is a pretty lodge (1874) in ‘cottage orné’ style, of red brick and sandstone with half-timbering.

We retraced our way all the way back along Princes St to Upper Parliament St, where we headed downhill.

The Old Toxteth Library (1903), on the left, was a branch library also designed by Thomas Shelmerdine, and constructed in red brick with stone dressings and a slate roof. This building, together with four other Liverpool branch libraries, was paid for by the American steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who came to Liverpool personally in 1902 to open it. He had Scottish ancestry linked to Liverpool, that recurring theme of immigration that runs through every strand of the city’s life. The library itself was recently refurbished and there was a ‘Through the Eye of The Tiger’ party to celebrate its re-opening, in recognition that it serves Europe’s oldest Chinese community based around Nelson St and has nearly a thousand regular Chinese customers.

We entered St James’s Cemetery (4 hectares, 10 acres) through a rather fine low rusticated arch as if we are entering a catacomb.

We entered St James’s Cemetery (4 hectares, 10 acres) through a rather fine low rusticated arch as if we are entering a catacomb.

In the eighteenth century, the site of the cemetery was a stone quarry, from which stones for the docks and other buildings were extracted. By 1825 the quarry was exhausted. A joint stock company was formed by Liverpool’s Anglican community to convert the site into a cemetery, which was consecrated in 1829. Entrances, carriage ramps, and buildings were designed by Liverpool architect John Foster (1787-1846). During 1810–11 he had accompanied C. R. Cockerell and the German archaeologists Haller and Linckh in their excavations of the temples at Aegina and Bassae, and this is no doubt where he got his classical inspiration from.

In 1901 the larger part of St James’s Mount and Walk, to the west of the cemetery, was chosen as the site for a new Anglican Cathedral on which work commenced in 1904. The cemetery was declared full in 1936, and in the late 1960s was cleared of most of its gravestones in favour of a public garden.

On our way through we read the inscriptions of many gravestones telling the lives of merchants and seamen and much else besides, and in the side of the hill, there are numerous catacombs, with round-arched entrances with rusticated surrounds.

On our way through we read the inscriptions of many gravestones telling the lives of merchants and seamen and much else besides, and in the side of the hill, there are numerous catacombs, with round-arched entrances with rusticated surrounds.

In the middle sits the Huskisson Mausoleum, as you undoubtedly remember from your history the first man to be killed by a train, on the inaugural journey of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1830.

BACK TO THE CITY ‘LOOP’

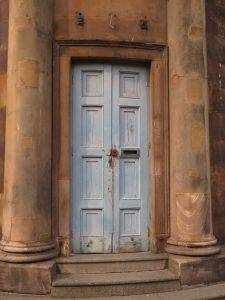

The Oratory (1829), the former mortuary chapel, is situated on high ground on a steep rocky eminence at the north-west corner of the cemetery, which we spotted immediately we start heading down Duke St (or from St James Cemetery if you are coming that way, atop a hill rather like the Acropolis). Designed by John Foster, it is in the form of a miniature Greek Doric temple. At each end is a portico with six columns. There are no windows and the building is lit from above. In the National Heritage List for England, it is described as “one of the purest monuments of the Greek Revival in England”.

The Oratory (1829), the former mortuary chapel, is situated on high ground on a steep rocky eminence at the north-west corner of the cemetery, which we spotted immediately we start heading down Duke St (or from St James Cemetery if you are coming that way, atop a hill rather like the Acropolis). Designed by John Foster, it is in the form of a miniature Greek Doric temple. At each end is a portico with six columns. There are no windows and the building is lit from above. In the National Heritage List for England, it is described as “one of the purest monuments of the Greek Revival in England”.

It is hard to sum up Liverpool (Anglican) Cathedral better than the Pevsner Guide does: “Liverpool cathedral, the life work of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, represents the final flowering of the Gothic revival as a vital, creative movement, and is one of the great buildings of the C20. Construction began in 1904 at the height of the city’s prosperity, and finished in 1978 as her long economic decline reached its lowest point. Funded to a large extent by the city’s merchant class, it marks the climax of the private patronage of public architecture that flourished in C19 Liverpool.”

It is hard to sum up Liverpool (Anglican) Cathedral better than the Pevsner Guide does: “Liverpool cathedral, the life work of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, represents the final flowering of the Gothic revival as a vital, creative movement, and is one of the great buildings of the C20. Construction began in 1904 at the height of the city’s prosperity, and finished in 1978 as her long economic decline reached its lowest point. Funded to a large extent by the city’s merchant class, it marks the climax of the private patronage of public architecture that flourished in C19 Liverpool.”

To me, at least, it is too big, almost monstrous in its size, but that is probably sacrilege to say so. I think I’d opt for the more intimate ‘wigwam’ down the road. For us, going to the top of the tower was an experience not to be missed, however, views in every direction and it helps you immediately ‘get’ the topography of the area. We spent nearly an hour up there, soaking in all the different landmarks and topographies, and seeing the direction from whence came the Welsh, the Irish and all the many different nationalities from the sea to settle in this melting pot.

To me, at least, it is too big, almost monstrous in its size, but that is probably sacrilege to say so. I think I’d opt for the more intimate ‘wigwam’ down the road. For us, going to the top of the tower was an experience not to be missed, however, views in every direction and it helps you immediately ‘get’ the topography of the area. We spent nearly an hour up there, soaking in all the different landmarks and topographies, and seeing the direction from whence came the Welsh, the Irish and all the many different nationalities from the sea to settle in this melting pot.

Sadly, Gilbert Scott’s proposals for Cathedral Gate were never adopted (the illustration of them looks very grand and imposing), and in its place, you get the Dean Walters Building, part of John Moores University, which is a horrible post-modern pastiche. No offence though to Dean Walters, who was clearly a great Dean. The wasteland around the cathedral was transformed under his leadership, with the building of Queen’s Walk and the John Moores University media studies block, which was named in his honour. There was also the creation of housing for students, for cathedral staff and public housing. This last was his contribution to the effort to reinstate inner-city living in Liverpool. It has been calculated that Walters was associated with developments worth, in total, some £230m.

Next up is Rodney St, sometimes called ‘The Harley St of the North’. There are over 60 Grade II listed buildings on this street and one II* church. No. 62 (1793) was the birthplace in 1809 of William Gladstone, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on four separate occasions through the 1860s to the 1890s. No. 59 Rodney Street was home and studio to Edward Chambré Hardman (1898–1988), photographer, and is now a National Trust property.

Next up is Rodney St, sometimes called ‘The Harley St of the North’. There are over 60 Grade II listed buildings on this street and one II* church. No. 62 (1793) was the birthplace in 1809 of William Gladstone, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on four separate occasions through the 1860s to the 1890s. No. 59 Rodney Street was home and studio to Edward Chambré Hardman (1898–1988), photographer, and is now a National Trust property.

Dr William Henry Duncan (1805-1863), born in No. 54, was Liverpool’s first Medical Officer of Health, from 1847 to 1863. He was one of the celebrated trio of pioneering officers appointed under the Liverpool Sanitary Act 1846, which became the precedent for later local and national legislation; the other two being James Newlands, Borough Engineer, and Thomas Fresh, Inspector of Nuisances (the title rather boringly changing to Sanitary Inspector in 1855, and more boringly still to Public Health Inspector in 1956).

He also was a proponent of the country’s first council houses, St Martin’s Cottages (in the Vauxhall part of the city), which were built in 1869. The city was bursting at the seams as its bustling docks and factories attracted many thousands of people from the countryside and from Ireland. In 1840, it was estimated that 39,000 people in Liverpool lived in squalid conditions in cellars and a further 86,000 in courts.

On unveiling a plaque to commemorate the site in 2001, the then Lord Mayor of Liverpool said, “the cottages may have been very basic and stark by modern standards but they were a revolution in their day. Social housing was transformed and as more and more councils followed Liverpool’s lead, millions of people were able to enjoy decent housing conditions and escape the squalor and slums of the Victorian area”. Sadly, these cottages were knocked down in the late 1970s.

We do a slight double back, up Mount St, then left onto Pilgrim St. Looking up Rice St on our right, we spied the unassuming Ye Cracke Public House, which was patronised by Liverpool art students from the adjacent art school for many years. John Lennon was apparently a frequent visitor, and his tutorials were sometimes conducted in a back room.

So much changes in Liverpool over the years and perhaps none more so than O’Connor’s Tavern, on the corner of Pilgrim St and Hardman St. Today it is ‘A taste of Two Cities’ Chinese restaurant. In the 1960s, it was at the heart of the Mersey Sound, hosting weekly musical performances and poetry reading from the soon to be famous trio of Roger McGough, Brian Patten and Adrian Henri.

Heading down Maryland St, the Aldham Robarts Learning Resource Centre (1993) is part of the John Moores University. Designed by architectural firm Austin-Smith: Lord and built in 1994, it has won several architectural awards. We admired the landscaped grounds around it.

On our right, as we came back out into Rodney Street stands the (disused) Scottish Presbyterian Church of Saint Andrew (1824) by John Foster. The façade of blackened ashlar is an imposing composition of Ionic entrance columns, flanked by corner towers, topped with Corinthian columns and domes. In 2012 the building was renovated and redeveloped to provide accommodation for 100 students.

And the churchyard is not like any old churchyard, with serried ranks of gravestones, some slightly larger than others to denote greater fame or deeper pockets. Here one stands out way above all others, an imposing fifteen-foot pyramid shaped tombstone, which looks rather like what you might imagine a nuclear bunker for Egyptians to look like. This is the grave of William MacKenzie, interred in 1851, whose name is mentioned in many Liverpool guidebooks. The story goes that MacKenzie, an Anglo-Scottish civil engineer, was a keen gambler and left instructions that he should be entombed above ground within the pyramid, sitting upright at a card table and clutching a winning hand of cards. I feel like a killjoy to add that this was apparently checked out a few years back and found to be an urban myth (apparently they used Spades to get in…)

And the churchyard is not like any old churchyard, with serried ranks of gravestones, some slightly larger than others to denote greater fame or deeper pockets. Here one stands out way above all others, an imposing fifteen-foot pyramid shaped tombstone, which looks rather like what you might imagine a nuclear bunker for Egyptians to look like. This is the grave of William MacKenzie, interred in 1851, whose name is mentioned in many Liverpool guidebooks. The story goes that MacKenzie, an Anglo-Scottish civil engineer, was a keen gambler and left instructions that he should be entombed above ground within the pyramid, sitting upright at a card table and clutching a winning hand of cards. I feel like a killjoy to add that this was apparently checked out a few years back and found to be an urban myth (apparently they used Spades to get in…)

Next, we headed past St Luke’s Church (1832), often referred to as the ‘bombed out’ church because it was largely destroyed during the Liverpool Blitz of 1941. Liverpool was the most heavily bombed area of the country outside London, due to its strategic importance to the British war effort, and around 4,000 citizens were killed. St Luke’s now stands as a memorial to those who were lost in the war and is also a venue for exhibitions and events.

We boldly go down Bold St, part of an area called The Rope Works, the name derived from the craft of rope-making for sailing ships that dominated the area until the 19th century. Ropes were made in fields but ropemakers bought or rented thin long strips of land. It was the sale of these thin strips, one by one at different times, that led to long thin streets with few interconnections, the roperies pre-dating the streets. Nelson’s HMS Victory had 32kms (20 miles) of rope in its rigging, which gives an indication of the demand for rope. This was an important industry for Liverpool well into the nineteenth century when sailing ships still reigned supreme.

Concert Square and its immediate surrounding area are at the heart of the city’s nightlife. The first development by Urban Splash Architects (we have seen their work on the Manchester, Plymouth and Birmingham Urban Rambles) saw the creation of apartments and commercial space. It is now home to many bars, galleries and creative businesses. Concert Square received a RIBA Award for Architecture in 1996 and was widely recognised for kick-starting the regeneration of this area of the city.

Concert Square and its immediate surrounding area are at the heart of the city’s nightlife. The first development by Urban Splash Architects (we have seen their work on the Manchester, Plymouth and Birmingham Urban Rambles) saw the creation of apartments and commercial space. It is now home to many bars, galleries and creative businesses. Concert Square received a RIBA Award for Architecture in 1996 and was widely recognised for kick-starting the regeneration of this area of the city.

Once out of the Rope Works area, we passed under the ‘Bling Bling’ Building, home to Herbert’s Hairdressing Salon and School. Architect Piers Gough had said that he wanted a building that would match the personality of owner Herbert Howe, describing him as ‘the king of bling’. It’s a fun building.

From the ridiculous (but enjoyable) to the sublime, one of Liverpool’s oldest surviving buildings, Bluecoat Chambers, built in 1716-17 as a charity school. Since the early 20th century it has been an arts centre, one of the first arts centres in the country. Today it is home to over 30 creative industries including artists, graphic designers, small arts organisations, craftspeople and retailers.

From the ridiculous (but enjoyable) to the sublime, one of Liverpool’s oldest surviving buildings, Bluecoat Chambers, built in 1716-17 as a charity school. Since the early 20th century it has been an arts centre, one of the first arts centres in the country. Today it is home to over 30 creative industries including artists, graphic designers, small arts organisations, craftspeople and retailers.

Peter’s Lane, Manesty’s Lane, Thomas Steers Way, Chavasse Park are all part of Liverpool ONE (2008), the largest open-air shopping centre in the UK and the 5th largest overall. Each store was created by a different architect, giving the area more character and individuality than your average shopping centre (eclectic or chaotic, take you adjectival pick, but definitely better than all the same, although I know Bath wouldn’t agree).

The reinstated Chavasse Park, rising in terraces from Strand Street to pavilions on a terrace above South John St, conceals a 3,000-space underground car park. The park works because it opens out and connects the docks area with the main town, despite, the dual carriageway that cuts them in two. This is where the Liverpool Overhead Railway (1893) used to run. At its peak, almost 20 million people used the railway every year. Sadly in 1955, a report into the structure of the many viaducts showed major repairs were needed that the company could not afford. The railway closed at the end of 1956 and despite public protests, the structures were dismantled in the following year.

The reinstated Chavasse Park, rising in terraces from Strand Street to pavilions on a terrace above South John St, conceals a 3,000-space underground car park. The park works because it opens out and connects the docks area with the main town, despite, the dual carriageway that cuts them in two. This is where the Liverpool Overhead Railway (1893) used to run. At its peak, almost 20 million people used the railway every year. Sadly in 1955, a report into the structure of the many viaducts showed major repairs were needed that the company could not afford. The railway closed at the end of 1956 and despite public protests, the structures were dismantled in the following year.

Deep breath. Now we are about to enter one of the most amazing bits of industrial history you will ever experience. Herman Melville the American author, in Liverpool on his first seafaring voyage in 1839, marvelled at Liverpool’s docks and compared them with the Great Wall of China and the Pyramids of the Pharos. Nowadays, of course, there is none of the intense activity of yesterday; but, in its place has been an intelligent reworking of the industrial footprint that leaves much to explore and enjoy. This part of Liverpool is at the core of why the city was designated a UNESCO designated World Heritage Site (an accolade they are struggling to hold on to as re-development and restoration continue to vie).

UNESCO’s rationale for designation sum things up well:

- Liverpool was a major centre generating innovative technologies and methods in dock construction and port management in the 18th and 19th centuries. It thus contributed to the building up of the international mercantile systems throughout the British Commonwealth.

- The city and the port of Liverpool are an exceptional testimony to the development of maritime mercantile culture in the 18th and 19th centuries, contributing to the building up of the British Empire. It was a centre for the slave trade, until its abolition in 1807, and for emigration from northern Europe to America.

- Liverpool is an outstanding example of a world mercantile port city, which represents the early development of global trading and cultural connections throughout the British Empire.

The imposing Dock Traffic Office (1847) building by Philip Hardwick is now the International Slavery Museum. Its portico is a tour de force in cast iron; each column is made of two sections over 17 feet high and the architrave is a single casting.

The Albert Dock (1846) is one of the great monuments of nineteenth-century engineering. Pevsner says of it: “For sheer punch there is little in the early commercial architecture of Europe to emulate it.” Designed by Jesse Hartley and Philip Hardwick, it was the first structure in Britain to be built from cast iron, brick and stone, with no structural wood, making it the first non-combustible warehouse system in the world.

The Albert Dock (1846) is one of the great monuments of nineteenth-century engineering. Pevsner says of it: “For sheer punch there is little in the early commercial architecture of Europe to emulate it.” Designed by Jesse Hartley and Philip Hardwick, it was the first structure in Britain to be built from cast iron, brick and stone, with no structural wood, making it the first non-combustible warehouse system in the world.

At the time of its construction, the Albert Dock was considered a revolutionary docking system because ships were loaded and unloaded directly from/to the warehouses. Two years after it opened it was modified to feature the world’s first hydraulic cranes. Due to its open yet secure design, the Albert Dock became a popular store for valuable cargoes such as brandy, cotton, tea, silk, tobacco, ivory and sugar. However, despite the Albert Dock’s advanced design, the rapid development of shipping technology meant that within 50 years, larger, more open docks were required, although it remained a valuable store for cargo. It finally ceased operation as a dock in 1972 and fell into neglect, until restored in the late 1980s.

Heading north along the waterfront, the Museum of Liverpool (2001) looms up in front of us. Its merits were always likely to be chewed over since this is such a sensitive site, I personally like it and it sits just fine amongst its more famous neighbours.

Heading north along the waterfront, the Museum of Liverpool (2001) looms up in front of us. Its merits were always likely to be chewed over since this is such a sensitive site, I personally like it and it sits just fine amongst its more famous neighbours.

The southernmost building of the famous pier head trio of the Three Graces is the Port of Liverpool Building (1907), in the Edwardian Baroque style and notable for the large dome that sits atop it, acting as the focal point of the building. Like the neighbouring Cunard Building, it is impressive for its ornamental detail, and in particular for the many maritime references and expensive decorative furnishings. Next up is The Cunard Building (1917), designed in a mix of Italian Renaissance and Greek Revival style. Finally, The Royal Liver Building (1911) is one of the most recognisable landmarks in the city and is home to two fabled Liver Birds that watch over the city and the sea.

The southernmost building of the famous pier head trio of the Three Graces is the Port of Liverpool Building (1907), in the Edwardian Baroque style and notable for the large dome that sits atop it, acting as the focal point of the building. Like the neighbouring Cunard Building, it is impressive for its ornamental detail, and in particular for the many maritime references and expensive decorative furnishings. Next up is The Cunard Building (1917), designed in a mix of Italian Renaissance and Greek Revival style. Finally, The Royal Liver Building (1911) is one of the most recognisable landmarks in the city and is home to two fabled Liver Birds that watch over the city and the sea.  Legend has it that were these two birds to fly away, then the city would cease to exist. So far so good, they’re still there. The clock faces are twenty-five feet in diameter, making them the largest striking clocks in the UK.

Legend has it that were these two birds to fly away, then the city would cease to exist. So far so good, they’re still there. The clock faces are twenty-five feet in diameter, making them the largest striking clocks in the UK.

The Titanic Memorial is dedicated to the 244 engineers, many from Liverpool, who lost their lives in the disaster as they remained in the ship supplying the stricken liner with electricity and other amenities for as long as possible. The monument is notable as the first monument in the UK to depict the working man.

The Church of Our Lady and St Nicholas (Patron Saint of Sailors) is the Anglican parish church of Liverpool. There has been a church on this site since the 13th century, although it has been rebuilt many times including after the tragedy of the spire collapsing in the 19th century. The pleasant churchyard was laid out in 1891 as a public garden.

The Church of Our Lady and St Nicholas (Patron Saint of Sailors) is the Anglican parish church of Liverpool. There has been a church on this site since the 13th century, although it has been rebuilt many times including after the tragedy of the spire collapsing in the 19th century. The pleasant churchyard was laid out in 1891 as a public garden.

We head up Water St and soon on our left we see the Oriel Chambers (1864), the world’s first building featuring a metal framed glass curtain wall. It was extremely poorly received by the critics of the day, but in the 20th century Pevsner called it “one of the most remarkable buildings of its date in Europe”. How perceptions can change. The delicacy of the ironwork in the plate-glass oriel windows and the curtain walling at the back with the vertical supports retracted yet visible from outside is way ahead of its time. This building directly influenced the modernist Chicago School of Architecture and the first skyscrapers built there towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Built as headquarters for Martins Bank (1932) by Herbert H. Rowse, No. 4 Water St, the building is now earmarked to be a 5* hotel. Its design perfectly expresses the American classicism promoted through Charles Reilly’s Liverpool School of Architecture.

Exchange Flags square takes its name from the flagstones that used to cover the square. In the 19th century, it formed an open-air exchange floor. The Nelson monument in the middle was Liverpool’s first piece of sculpture, erected in 1813. And if you look carefully at the two Sir Gilbert Scott telephone boxes as you go into the square, you will notice that one is the rarer K2 version (three equal glass panels), designed in 1924. So today we have seen Sir Gilbert’s largest ever architectural structure (The Anglican Cathedral) and his smallest (the ‘phone box).

The Town Hall (1754) is that relatively unusual thing in Liverpool, an early Georgian building, “one of the finest surviving 18th-century town halls”. It was built to a design by John Wood the Elder (of Bath fame) replacing an earlier town hall nearby.

The Town Hall (1754) is that relatively unusual thing in Liverpool, an early Georgian building, “one of the finest surviving 18th-century town halls”. It was built to a design by John Wood the Elder (of Bath fame) replacing an earlier town hall nearby.

During the eighteenth-century Castle St was known as the Fleet St of Liverpool because of the many newspaper offices located in the area. There are so many buildings of note in this street, just cast your eyes up and get your hands on a copy of the Pevsner Guide if you crave more details. Sir James Picton said that ‘The history of Castle St is the history of Liverpool’ and this fine street remains the identifiable centre of the city.

I will draw your attention to just three of the most notable buildings as you head down it:

On the west side at No. 22 is The National Westminster Bank Building (1900), designed by Norman Shaw. It is constructed from granite of alternating yellow and grey stripes and has terracotta window dressings and a slate roof.

The Bank of England Building (1848) is a Grade I listed building on the corner on the left just before Cook St. It was designed by Charles Robert Cockerell and built in Neoclassical style. The building is regarded as one of his most impressive and was described by Pevsner as a “masterpiece of Victorian architecture”.

The Bank of England Building (1848) is a Grade I listed building on the corner on the left just before Cook St. It was designed by Charles Robert Cockerell and built in Neoclassical style. The building is regarded as one of his most impressive and was described by Pevsner as a “masterpiece of Victorian architecture”.

Opposite it on Brunswick St is the former Adelphi Bank (1890) (now a Costa) by WD Cranoe, with its unusual copper ‘onion’ dome.