Moving forwards – the horse, the canal, the railway, the highway, the information superhighway…

This final stage of the Inner London Circuit takes us through Little Venice and along a charming stretch of the Regent’s Canal, passing through two of London’s finest open spaces, Regent’s Park and Primrose Hill.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 10 km (6.25 miles)

- Typical time: 2 ½ hours

- Height change: 40 metres

- Start: Lancaster Gate Tube Station (W2 2UE)

- End of this stage: King’s Cross Station (N1C 4TB)

- Terrain: Straightforward; sturdy footwear recommended

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Norfolk Square, Floating Pocket Park, Sheldon Square, The Regent’s Park, Queen Mary’s Rose Gardens, Primrose Hill, Camley St Natural Park, St Pancras Gardens |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Paddington Basin, Grand Junction Canal, Little Venice, The Regent’s Canal, Tyburn River (underground) |

| Stunning cityscape | Primrose Hill |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Georgian (1714-1836) | The original buildings in Regent’s Park; the early buildings in the London Zoo |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Paddington Station (1854), The Catholic Apostolic Church (1890s), Crocker’s Folly (1898), St Pancras Station (1868) |

| Industrial Heritage | The Paddington Basin (1801), Interchange Warehouse (1905), Gasholder Park (1850s), Coal Drops Yards (1850s) |

| Modern (post-1918) | GWR Paddington Office (1935), The Fan Bridge (2014), The Rolling Bridge (2004), The Battleship Building (1969), The London Central Mosque (1978), The Round House and the Penguin Pool at the zoo (1933-34), The Snowdon Aviary (1964), TV-am building (1982), Grand Union Walk (1988), the Francis Crick Institute (2016), The British Library (1999) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Bathurst Deli, Waterside Café, Café Laville, The Hub |

| Quirky Shopping | Regent’s Park Rd, Primrose Hill; Camden Market; Coal Drops Yard (from 2018) |

| Places to visit/things to do | Hyde Park Stables, Ross Nye Stables, Alexander Fleming Museum, Regent’s Park Boating, London Zoo, Camley St Natural Park |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Canalway Cavalcade Festival, Little Venice (early May); Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre (May-Sept); Primrose Hill Summer Festival (May) |

City population: 8,538,689 (2011 census)

Urban population: 9,787,426 (2011 census)

Ranking: Largest city in the UK

Date of origin: 43AD

‘Type’ of city: capital city; seat of government, commerce and culture.

City status: Since time immemorial

Notable city architects/planners: John Nash (1752-1835) – Regent’s Canal, Regent’s Park

Number of Listed Buildings: Westminster – 3,933, of which 206 are Grade I and 364 are Grade II*; Camden – 1,949, of which 56 are Grade I and 155 are Grade II*

Films/TV series shot here:

Bathurst Mews: Scandal (1989) – 42 was used as the home of Stephen Ward.

Paddington Basin: Bourne 5 (2016)

Little Venice: Georgy Girl (1966); A Fish Called Wanda (1988); Killing Me Softly (2002). See A Cinematic Stroll through Little Venice

Regent’s Park Zoo: An American Werewolf in London (1981); Withnail and I (1987); Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), About a Boy (2002) Boating Lake: Brief Encounter (1945)

Primrose Hill: Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004)

THE CONTEXT

When I have done a walk, I always try and work out if there is an overall theme to the route, something that makes sense of it and brings it all together. And this stage fell into place very quickly –it’s a story about the evolution of transport & communication and the way in which regeneration takes place once a particular stage of transport or communication technology has been superseded.

So, we start in a mews, symbol of the coach and horse age, the ‘service conduits’ for the big houses on either side, morphing in the 1960s to trendy places for people to live, and today achingly hip and expensive, but still with a country feel about them when you stroll along past their back to front gardens spilling onto the cobbles.

Then to Paddington Basin, which at the start of the nineteenth century became the hub of ‘goods inwards’ to central London, bringing building materials and coal along the canal from the Midlands; now, completely regenerated with office, apartments, restaurants and quirky bridges.

Next, under the Westway, that concrete memorial to the motor car, crashing through London in the 1960s preceded by a wrecking ball, intended to relieve congestion and kick-start a new age of modernism in which the car would be king (thankfully past now). But the thumping noise and ugliness are still there, reminding us of just how horrible most UK cities were in the 70s.

Then, passing through the elegant Regent’s Park, which used to be a royal hunting ground but was ‘regenerated’ as a smart place for Georgians to hang out and promenade in; allowing wild animals back, but strictly in captivity (aka the zoo).

And towards the end of the walk, observing redundant railway yards transformed into seats of learning (The British Library, the Francis Crick Institute) or up-market shopping arcades (Coal Drops Yard). Even an old gas works which has become a circular garden.

And finally, the headquarters of Google alongside King’s Cross, laying down the Information Superhighway in what used to be just a railway siding and supplying the mapping with which all my walks are driven – for which many thanks – first the Ordnance Survey then Google have transformed our sense of place and our enjoyment of the outdoors.

THE WALK

Old communication

We set out from Lancaster Gate Station on the final leg of our journey and decided to explore some of the many mews in this part of the capital. We know that mews used to be the ‘service conduits’ for the grand town houses on either side, where the horses, carriages (downstairs) and staff (upstairs) were housed whilst their masters were staying in London, but we thought that the stables had long gone in favour of bijoux conversions for folk looking for a more ‘individualistic’ lifestyle. But not Bathurst Mews. Bathurst Mews has two stable yards that are alive and kicking (figuratively speaking). And, the day we passed through, both stables were grooming and tacking up their ponies ready to take groups around Hyde Park at whatever speed their skill allowed. It felt suddenly like being thrust back into a childhood of pony clubs and oh so many brushes, with lots of kids, most excited and a few a little apprehensive, waiting in the cleanest jodhpurs and boots to mount their miniature steeds.

According to Hyde Park Stables manager, Catherine Brown, “There have been horses here continually since 1835, aside from just two years in the Second World War when the building was used for motor vehicles.” The Ross Nye Stables has ‘only’ been going since 1965 (at around the time that ‘mews’ became really fashionable – think of Michael Caine’s Charlie Croker in The Italian Job, and Twiggy posing in front of a mini), but it’s still in the same family. Ross, who first opened the stables, grew up in Queensland and worked on a cattle station with his brother for ten years. They rode all day long over rough country and were involved in all aspects of horse care – from breeding to breaking in, from mustering cattle to picnic races. Rotten Row with its sandy base must have felt like a bit of a doddle.

but it’s still in the same family. Ross, who first opened the stables, grew up in Queensland and worked on a cattle station with his brother for ten years. They rode all day long over rough country and were involved in all aspects of horse care – from breeding to breaking in, from mustering cattle to picnic races. Rotten Row with its sandy base must have felt like a bit of a doddle.

We are now heading through the Hyde Park Estate, which is bounded by Sussex Gardens, Bayswater Road and Edgware Road. Most the 1,700 or so freehold interests within the estate are owned by the Church Commissioners for England. It was given the name ‘Tyburnia’ when the area was first developed in the early 19th century to try and give it a catchy title to match Belgravia’s but, perhaps unsurprisingly as the name is more associated with gallows (the Tyburn ‘gallows’ tree was at Marble Arch) than lifestyle, the name didn’t stick. The ever-optimistic estate agents of the 21st century are trying to resurrect the name Tyburnia to give the area a marketing ‘hook’, as rates are still lower than other parts of the capital (but don’t get excited, you still won’t be able to afford it).

Norfolk Square was laid out in the 1840s on the site of the former Upper South Reservoir of the Grand Junction Canal Company (regeneration of redundant technology). The garden was originally provided for the private use of the residents of the square. They had their own constable who patrolled daily and acted as gateman. The ladies of the houses would take afternoon tea in the gardens, served by their maids in the shade of the trees.

The area later became invaded by minor hotels, and a block of flats replaced the church that had burnt down at the east end of the square. Consequently, the garden became neglected and in 1989 was acquired by Westminster City Council through compulsory purchase. It was completely re-landscaped with new paths, shrub planting and railings and today is well, rather than brilliantly maintained.

If you are passing in the warmer months (May to October) you will see ‘Paddingtonscape’ by Hannah Warren, a Paddington Bear statue in the square featuring the various landmarks and street scenes in and around Paddington. Like every good bear though, he hibernates during the winter months (November to March) at the Hilton London Paddington.

Paddington Station was designed by Brunel, who is commemorated by a statue on the concourse (there is a matching statue of him standing in Bristol Temple Meads), although much of the architectural detailing was by his associate Matthew Digby Wyatt. It opened in 1854 and is regarded as one of the country’s finest stations architecturally, albeit not as spectacular on approach as St Pancras Station.

We loved the art deco GWR Paddington Building up London St just before we turned right down Winsland Mews. It dates back to the mid-1930s and has many art deco features, including a row of shell-like protrusions which contain the lights that illuminate the sign. Love this building.

We loved the art deco GWR Paddington Building up London St just before we turned right down Winsland Mews. It dates back to the mid-1930s and has many art deco features, including a row of shell-like protrusions which contain the lights that illuminate the sign. Love this building.

On the right, Paddington’s handsome former Royal Mail Sorting and Delivery Office with its distinctive Baroque detailing is one of many important structures around Paddington Station reflecting the development of the railways. The time of ‘snail mail’ is nearly done and the building is no longer in use. At the time of writing, there’s a bit of a battle on to preserve it. Even though it was recognised by Westminster City Council as a ‘Building of Merit’ as recently as 2010, they are now considering allowing its demolition to make way for a new residential tower nicknamed the ‘Paddington Cube’. Daft.

St Mary’s Paddington Hospital is a rabbit warren of buildings that started life around the middle of the nineteenth century. There are frequent plans for rationalisation and enhancement, but so far not realised. The most notable building is in Praed St, which we come to in a few moments, the Clarence Memorial Wing Hospital, built by Sir William Emerson at the start of the last century. Heritage England describes it as in an ‘eclectic Renaissance style’.

On the outer wall, there is a plaque commemorating the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in this wing in 1928. The tiny laboratory has been restored and can be visited. The maternity unit has recently specialised in bringing future monarchs into the world, with Prince William and George both being born here (as well as their respective younger siblings Harry & Charlotte).

Grand Junction Arms (now Fantasia Greek restaurant) at 28 Praed Street is a charming 1930s corner public house building, with mock Tudor detailing to upper storey and faience facade below. Not being listed, it’s liable at any time to be knocked down, which would be a shame. Corner sites and pubs go together like ham and cheese!

Grand Junction Arms (now Fantasia Greek restaurant) at 28 Praed Street is a charming 1930s corner public house building, with mock Tudor detailing to upper storey and faience facade below. Not being listed, it’s liable at any time to be knocked down, which would be a shame. Corner sites and pubs go together like ham and cheese!

The Paddington Basin opened in 1801 and was the terminus of the Grand Junction Canal before the Regent’s Park arm was constructed a decade or so later. The site was chosen because of its position on the New Road which led to the east, providing for onward transport into the city. In its heyday, the basin was a major transhipment facility and a hive of activity. After many years of neglect, the basin has now been completely re-developed, although it can still feel a little soulless. But basically, I feel it does everything just about right – good spaces, good materials, art and interesting bridges, hopefully the bustling life will follow, it certainly works on a summer’s day. It’s definitely a very great deal better than it used to be. As we entered through the arch, we saw the Floating Pocket Park, apparently the first of its kind in London, floating on pontoons, with lawns, raised borders, seating areas and a separate wildlife island to encourage waterfowl. So London does have a garden over water after all, just not the Thames…

If unusual bridges are your thing, then The Basin is the place to come as you will cross two. The Fan Bridge (2014) gracefully splays as it rises, while the Rolling Bridge (2004), conceived by Thomas Heatherwick, curls itself up into a ball like a shy caterpillar. Both bridges ‘perform’ on Wednesday and Friday at 12noon (fan first, then rolling) and Saturday afternoons at 2 pm; so, next time you’re in the area, go and catch the show. Failing that, you can see them on video at http://londonist.com/2015/04/video-paddington-basins-incredible-bridges

Located just beneath Bishops Bridge, ‘Message from the Unseen World’ (2016) is a homage to Alan Turing, who was born in Paddington in 1912 and became a founding father of computer science. The blurb says that this is ‘a dynamic artwork; a machine trying to write like a poet, whilst thinking like a machine.’ Clear on that?

Located just beneath Bishops Bridge, ‘Message from the Unseen World’ (2016) is a homage to Alan Turing, who was born in Paddington in 1912 and became a founding father of computer science. The blurb says that this is ‘a dynamic artwork; a machine trying to write like a poet, whilst thinking like a machine.’ Clear on that?

Sheldon Square, forming the major part of Paddington Central, is an impressive recently created space with a grass amphitheatre that features live music in summer, but inevitably in the rush to get it open they have given most of the concessions to chains – this place feels the exact opposite of the free spirit of Camden Market, which we come to later.

Just before we went under the inferno of noise known as the Westway we saw a man standing and a man walking. Well, actually two bronze sculptures set apart by several metres, entitled Standing Man & Walking Man by Sean Henry (2004). Very realistic, and mistaken at dusk no doubt for the real thing.

So, what is to be said about the Westway? Well. All that was bad about 1960s planning really… the road was constructed between 1964 and 1970 to relieve congestion at Shepherd’s Bush caused by traffic from Western Avenue struggling to enter central London. The route of the Westway was chosen to follow the easiest path from Western Avenue to Paddington by following the route of existing railway lines. Passing an eight-lane elevated motorway through densely populated Victorian North Kensington, though, involved the clearance of a large number of buildings adjacent to the railway, particularly in the area west of Westbourne Park, where many roads were unceremoniously truncated or demolished to make way for the concrete structures.

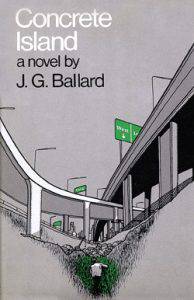

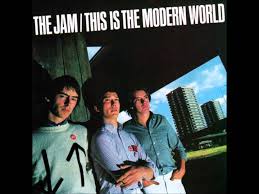

Oddly though the Westway seems to have inspired creative thinking, cropping up in the songs of the Clash and the Blur and featured on the front cover of The Jam’s ‘This Is The Modern World’. But its most famous outing was the dystopian vision of author JG Ballard in the 1974 novel Concrete Island, in which an architect is marooned Crusoe-like on a triangular strip of motorway intersection when his car plunges off the exit road after a tyre blowout:

Oddly though the Westway seems to have inspired creative thinking, cropping up in the songs of the Clash and the Blur and featured on the front cover of The Jam’s ‘This Is The Modern World’. But its most famous outing was the dystopian vision of author JG Ballard in the 1974 novel Concrete Island, in which an architect is marooned Crusoe-like on a triangular strip of motorway intersection when his car plunges off the exit road after a tyre blowout:

“Soon after three o’clock on the afternoon of April 22nd 1973, a 35-year-old architect named Robert Maitland was driving down the high-speed exit of the Westway interchange in central London. Six hundred yards from the junction with the newly built spur of the M4 motorway, when the Jaguar had already passed the 70-m.p.h. speed limit, a blow-out collapsed the front nearside tyre [sic]. The exploding air reflected from the concrete parapet seemed to detonate inside Robert Maitland’s skull.” For a very nerdy account of where this happened, check out; http://www.ballardian.com/the-real-concrete-island (loved it).

It is the very opposite vision of William Morris’s ‘News from Nowhere’ in which London morphs into a pleasant idyll bedecked with trees and fabulous breezes. But I also love a recent online article in the Londonist entitled: ‘What’s Really Happening Alongside the Westway?’ in which you see that, despite its brutal intrusion on everyday life, people still get on with their lives.

Being an architect, Robert Maitland would surely have noticed The Battleship Building (alongside the Westway on the north side) on his fateful journey, and maybe that was when he started feeling all at sea. The building was originally designed in 1969 as a British Rail maintenance depot. It is in the ‘streamline moderne’ style, a style that emphasised curving forms, long horizontal lines and sometimes nautical elements. It won the Concrete Society’s ‘Building of the Year’ in 1969 (an accolade to be proud of presumably; it’s still there on the side of the building) and was listed Grade II* in 1994.

Being an architect, Robert Maitland would surely have noticed The Battleship Building (alongside the Westway on the north side) on his fateful journey, and maybe that was when he started feeling all at sea. The building was originally designed in 1969 as a British Rail maintenance depot. It is in the ‘streamline moderne’ style, a style that emphasised curving forms, long horizontal lines and sometimes nautical elements. It won the Concrete Society’s ‘Building of the Year’ in 1969 (an accolade to be proud of presumably; it’s still there on the side of the building) and was listed Grade II* in 1994.

Then we arrive in the exact opposite of urban displacement, the oozing gentility of Little Venice, where the Paddington Spur meets the Grand Union and the Regent’s Canal. But it was not always like this. In its bustling heydey, it would have had a very industrial feel to it, with the movement of food and materials, especially coal.

I am not convinced that Lord Byron coined the phrase ‘Little Venice’ as urban folklore suggests. It is only in the last fifty years or so that the name Little Venice has come into use, and one suspects it was much more driven by a developing property market than poetic overtones. Sorry. But Lord Byron did apparently contrast this part of Paddington to Venice and wished it was so much more like its Italian counterpart.

Browning’s Pool is another popular gentrification of the area. The islet in the middle of the pool was christened Browning’s Island. Anyhow, in the 1860s Robert Browning did live here, opposite the pool itself in Warwick Crescent (since rebuilt).

The Lock-Keeper’s House next to Warwick Avenue Bridge was built in 1819 at the insistence of the Grand Junction Canal Company, to house the toll collector and to ensure no water flowed into the Regent’s Canal. If you look closely, you will see two redundant stop-locks for this purpose, which every barge passing between the two canals had to enter.

The Lock-Keeper’s House next to Warwick Avenue Bridge was built in 1819 at the insistence of the Grand Junction Canal Company, to house the toll collector and to ensure no water flowed into the Regent’s Canal. If you look closely, you will see two redundant stop-locks for this purpose, which every barge passing between the two canals had to enter.

The stuccoed buildings of Blomfield Rd were built between 1830 and 1850, not long after the canal was opened. Whilst today the views are idyllic when built the canal would have been full of industrial cargo and for that reason, the houses were well set back. Nancy Mitford chose 12 Blomfield Rd as her home in the 1930s and Poet Laureate John Masefield lived on the other side in Maida Avenue as did Noel Gallaher. Sir Richard Branson famously lived and worked on a houseboat boat called Duende near here in the 1980s (still to be found up the other spur).

A Time of Silence

There’s also a rather fine Victorian church (built 1891–1894) looming up on our right. Further research shows it to be one of the last remaining active Catholic Apostolic Churches, a religious movement that originated in England around 1831.

There’s also a rather fine Victorian church (built 1891–1894) looming up on our right. Further research shows it to be one of the last remaining active Catholic Apostolic Churches, a religious movement that originated in England around 1831.

The immediate Second Coming of Christ was the central aim of the congregations, and a new order of Apostles was deemed necessary to prepare the whole church for this event. Unfortunately, following the death of the last of these Apostles in 1901, and still no sign of the second Coming, no further ordinations were possible.

Gradually, the surviving ministers died off until, by the mid-20th century, no ordained ministers remained and the sacraments of the Catholic Apostolic Church could no longer be celebrated. Surviving followers of the Catholic Apostolic Church could still meet for worship and prayer, but they could not continue the elaborate Liturgy that required ordained ministers.

Adherents were encouraged to share in the public worship of other Christian bodies, such as the Church of England. The Catholic Apostolic Church entered a ‘Time of Silence’. Many of the Catholic Apostolic buildings were sold off or leased. Today, the only active Catholic Apostolic congregation is this one, on the banks of the canal.

It was such a fine day, that we stopped for a glass of prosecco at Crocker’s Folly. The building itself looks strangely out of scale with its immediate residential surroundings. It turns out it’s a Grade II* listed building built in 1898, in a Northern Renaissance style. Every wall, window and ceiling are decorated in ornate style, with soaring pillars, wood panelling and elaborate stucco featuring gambolling cherubs. Its grand saloon used 50 types of marble to create a magnificent bar-top, archways, an enormous fireplace and soaring pillars, which in turn supported the opulent part-gilded beamed ceiling. Even the chimney and walls were faced with marble.

It was such a fine day, that we stopped for a glass of prosecco at Crocker’s Folly. The building itself looks strangely out of scale with its immediate residential surroundings. It turns out it’s a Grade II* listed building built in 1898, in a Northern Renaissance style. Every wall, window and ceiling are decorated in ornate style, with soaring pillars, wood panelling and elaborate stucco featuring gambolling cherubs. Its grand saloon used 50 types of marble to create a magnificent bar-top, archways, an enormous fireplace and soaring pillars, which in turn supported the opulent part-gilded beamed ceiling. Even the chimney and walls were faced with marble.

The story was that Frank Crocker built the pub to serve the new terminus of the Great Central Railway, but when the terminus was actually built it was over half a mile away at Marylebone Station, leading to Crocker’s ruin, despair and eventual suicide. The only thing it seemed to lack the day we were there were customers, we were the only ones; but sunning ourselves out the front we felt very contented nonetheless.

The next section of the canal after Lisson Grove is much broader. This was originally for commercial barges to load and unload at the Great Central Railway Goods Yard on the southern bank.

The Canal House on Lisson Grove is the only house that straddles the canal. It was built in 1906 for the manager of the Regent’s Canal.

The Lisson Grove Moorings are a delightful spot. Because of the canal being broader here, the boats are moored end on which means there is quite a community as communication between boats is much easier! And the residents have developed the towpath into a sort of linear garden, with deck chairs, trellises, roses and even a garden gnome making passers-by, including us, cry out in chorus ‘Wouldn’t it be just great to live on a canal boat!’

The Lisson Grove Moorings are a delightful spot. Because of the canal being broader here, the boats are moored end on which means there is quite a community as communication between boats is much easier! And the residents have developed the towpath into a sort of linear garden, with deck chairs, trellises, roses and even a garden gnome making passers-by, including us, cry out in chorus ‘Wouldn’t it be just great to live on a canal boat!’

But would it really ?! This is the view of a blogger called ‘Great Wren’:

“For half the year, living on the canal was an outdoors and sociable affair. This was partly a matter of comfort. Boats are largely made of glass and metal, so get very hot very quickly. It’s like living in a car. To combat this, doors were always open and much time was spent on deck, gossiping with neighbours. This easy familiarity would lead to impromptu barbeques that became boozy weekends, with individuals dropping in and out as the mood struck but the essential body of the party remaining intact from Friday evening to Sunday night.

“Then in winter, we hibernated. Returning in the evening gloom, even before you reached the canal, you’d catch the homely smell of smoking coal. The towpath would be still, and on every boat, doors and curtains would be closed against the cold, chimneys puffing cheerily away. While summer was a buzz of conversation, hailed hellos and clinking bottles, the sound of winter was the stolid rattle of a coal scuttle being filled.”

The Lord’s Cricket Ground that we know today, 250 or so metres north of our route, is actually the third incarnation of the ground. The first was at Dorset Fields (now Dorset Square) where the first match was played in 1787. But by 1809 London was expanding rapidly and rent was on the rise in Dorset Fields. Lord, the businessman who founded the ground, was looking elsewhere and that year he opened a new ground here where the canal now is.  The second Lord’s was unpopular, though; lacking in atmosphere, and with a difficult landlord who objected to the opening of a tavern – a central part of watching cricket at the ground, as of course, it is to this day.

The second Lord’s was unpopular, though; lacking in atmosphere, and with a difficult landlord who objected to the opening of a tavern – a central part of watching cricket at the ground, as of course, it is to this day.

There was a stroke of luck for Lord in 1812 though when he discovered that the Regent’s Canal was due to be built straight through his unloved cricket ground. With £4,000 in compensation, he gratefully accepted another plot of land slightly further up the road in St John’s Wood; the current Lord’s Ground, which had previously been a duck pond (no etymological link so far discovered with ‘being out for a duck’). The first match was played there in 1814 and the next one we’re off to see in a few days time.

Once past the Park Road bridges, the landscape becomes very country like as the canal enters Regent’s Park. It was originally intended to cut straight across the park, but the new residents in 1812 did not want the canal with industrial cargoes ruining their pastoral idyll. So, the canal had to arc around the northern perimeter of the park, cutting through the lower sections of St John’s Wood Hill.

The London Central Mosque was designed by Sir Frederick Gibberd, completed in 1978, and has a prominent golden dome. The land was originally donated by George VI in recognition of the importance of the Muslim community in British life and their contribution to the war effort.

As we look across the canal we see a run of very impressive classically-designed houses, but there is something not quite right about them. They look a little too perfect and somehow not quite lived in – unblemished stonework, straight lines, and no tell-tale signs of normal life – bulging bins, kid’s stuff in the garden, washing hanging on a line – in many ways they look unoccupied, which is a shame, not at all like most of the properties with frontage on the canals, which often have complicated sun decks and multi-coloured craft by the waterside.

As we look across the canal we see a run of very impressive classically-designed houses, but there is something not quite right about them. They look a little too perfect and somehow not quite lived in – unblemished stonework, straight lines, and no tell-tale signs of normal life – bulging bins, kid’s stuff in the garden, washing hanging on a line – in many ways they look unoccupied, which is a shame, not at all like most of the properties with frontage on the canals, which often have complicated sun decks and multi-coloured craft by the waterside.

In fact, they were only built in the 1990s. How you might ask then, did they ever get planning permission? Well, simple really. Firstly, there were buildings on the site already in the shape of Bedford College. Secondly, the creator of the Regent’s Park, the 18th-century architect John Nash, had intended to construct 48 villas in the park, but only eight were eventually built. So, in some respects these were the realisation of those houses, just coming 175 years or so late.

Quinlan Terry, the Neo-Classical English architect commissioned to build them, said the brief had been to “step into Nash’s shoes and carry on walking”. The villas are each in a different classical style, intended to be representative of the variety of classical architecture – the Veneto Villa, Doric Villa, Corinthian Villa, Ionic Villa, Gothick Villa and the Regency Villa .

Charlbert Street Bridge across the Regent’s Canal is designed for both aesthetic and practical purposes. Its gracious curves belie the fact it was also designed to accommodate the course of the Tyburn River. It is described in John Hollingshead’s ‘book ‘Underground London’ (1862) as follows: ‘an iron tube, about three-foot-high and two feet broad…through the crown of the bridge.’ The only visible evidence today of the footbridge’s real purpose is an inspection hatch that we walked over on our way into the park.

And now we take in a loop of The Regent’s Park (166 hectares, 410 acres); consider this loop optional, but we love green spaces and cannot pass one of the finest of all without this quick detour.

And now we take in a loop of The Regent’s Park (166 hectares, 410 acres); consider this loop optional, but we love green spaces and cannot pass one of the finest of all without this quick detour.

In the Middle Ages, the land was part of the manor of Tyburn, the property of Barking Abbey. In the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry VIII appropriated the land, and it has been Crown property ever since. It was set aside as a hunting park, known as Marylebone Park, until 1649, when it was let out in small holdings for hay and dairy produce.

When the leases expired in 1811, the Prince Regent (later King George IV) commissioned architect John Nash to create a masterplan for the area. Nash originally envisaged a palace for the Prince and several grand detached villas for his friends, but when this was put into action from 1818 onwards, the palace and many of the villas were dropped. However, most of the proposed terraces of houses around the fringes of the park were built. Nash did not complete all the detailed designs himself; in some instances, completion was left in the hands of other architects such as the young Decimus Burton. The Regent Park scheme was integrated with other schemes built for the Prince Regent by Nash, including Regent Street and Carlton House Terrace in a grand sweep of town planning stretching from St. James’s Park to Parliament Hill. The park was first opened to the public in 1835, initially only for two days a week.

This description by David Lloyd in The Making of English Towns (1984) sums the development up beautifully: “Nash had for several years been in partnership with Humphrey Repton, the great landscape designer in the Picturesque tradition – the basis of which was the creation artificially of irregular, apparently natural scenes such as might have been shown in a landscape picture of the time, hence the term. This could be achieved through studied planting, moulding of slopes and declivities, and often, where practicable, the formation of water expanses with intricate shorelines. Although the partnership was broken, Nash remained a superb landscapist and very much in the Repton manner, and this is seen in Regent’s Park today – particularly in the masterly effect of the branching islanded lake with its winding wooded shores, and the contrasts between wooded areas and sweeping grassy expanses. The lake was formed from two converging streams.”

We head south into the park, following almost exactly the route of one of these streams, the Tyburn, to the boating lake, passing the Open-Air Theatre (founded in 1932) to the Queen Mary’s Rose Gardens. It boasts London’s largest collection of roses with approximately 12,000 roses, including most rose varieties, from the classics to the most modern.

St John’s Lodge is a private residence just outside the Inner Circle, but the garden is open to the public to visit for free. It was designed by Robert Weir Shultz in 1889 as a series of compartments ornamented with sculpture and stonework and was intended to be a garden ‘fit for meditation’.

St John’s Lodge is a private residence just outside the Inner Circle, but the garden is open to the public to visit for free. It was designed by Robert Weir Shultz in 1889 as a series of compartments ornamented with sculpture and stonework and was intended to be a garden ‘fit for meditation’.

We now loop back up, roughly along the line of the other stream that feeds into the boating lake, a tributary to the Tyburn, skirting around the southern perimeter of London Zoo, opened in 1828 and the world’s oldest scientific zoo. It was established by Sir Stamford Raffles (a statesman) and Sir Humphry Davy (a prominent scientist) and was originally intended to be used as a collection for study. It was not opened to the public until 1847. Today it houses a collection of 756 species of animals, making it one of the largest collections in the United Kingdom.

Since its earliest days, the zoo has prided itself on appointing leading architects to design its buildings – consequently, it has two Grade I and eight Grade II listed structures. You wouldn’t think of coming to the zoo to look at architecture, but it definitely adds an extra dimension to the visit.

The grounds were first laid out in 1828 by Decimus Burton, the zoo’s first official architect from 1826 to 1841. He built the Clock Tower in 1828 and the Giraffe House in 1837, which is still used for that purpose today.

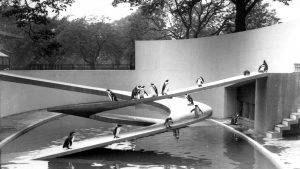

After Burton, Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell and John James Joass were appointed to design the Mappin Terraces. Completed in 1914, they imitate a mountain landscape to provide a naturalistic habitat for bears and other mountain wildlife. In 1933 the Round House, designed by Berthold Lubetkin’s Tecton Architectural Group to house gorillas, was one of the first modernist style buildings to be built in Britain. The following year the Penguin Pool, also designed by Tecton, was opened; both are now Grade I listed. The Modernist dual concrete spiral ramps of the Penguin Pool have made it famous, but during a 2004 refurbishment the penguins apparently took a strong liking to the duck pond they had been temporarily relocated to, and they were moved out of the Penguin Pool permanently. Great architecture can’t please all the penguins all the time.

After Burton, Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell and John James Joass were appointed to design the Mappin Terraces. Completed in 1914, they imitate a mountain landscape to provide a naturalistic habitat for bears and other mountain wildlife. In 1933 the Round House, designed by Berthold Lubetkin’s Tecton Architectural Group to house gorillas, was one of the first modernist style buildings to be built in Britain. The following year the Penguin Pool, also designed by Tecton, was opened; both are now Grade I listed. The Modernist dual concrete spiral ramps of the Penguin Pool have made it famous, but during a 2004 refurbishment the penguins apparently took a strong liking to the duck pond they had been temporarily relocated to, and they were moved out of the Penguin Pool permanently. Great architecture can’t please all the penguins all the time.

The Snowdon Aviary, built in 1964 by Cedric Price, Lord Snowdon and Frank Newby, made pioneering use of aluminium and tension for support. A year later the Casson Pavilion, designed by Sir Hugh Casson and Neville Conder, was opened as an elephant and rhinoceros house. The Pavilion was commissioned “to display these massive animals in the most dramatic way” and was designed to evoke a herd of elephants gathered around a watering hole.

Perhaps you were waylaid by the zoo and now it’s three hours later. So, when you’re ready, over Primrose Hill Bridge and onto Primrose Hill (83 hectares, 206 acres).

Like Regent’s Park, Primrose Hill was once part of a great chase appropriated by Henry VIII. Later, in 1841, it became Crown property and in 1842 an Act of Parliament secured the land as public open space. The built-up part of Primrose Hill comprises mainly Victorian terraces; the area was named after Archibald Primrose, whose premiership witnessed the rapid expansion of the London Underground.

A perfect day

“Where has that view gone?”

At the top of the hill (63 metres) is one of thirteen protected vistas in London, almost all of which involve views towards St Paul’s Cathedral (for a full list see Protected Vistas in London). In winter, Hampstead can be seen to the northeast. The summit features a York stone edging with a William Blake quote, that reads: ‘I have conversed with the spiritual sun. I saw him on Primrose Hill.’ He lived in Fitzroy Rd, which is on the east side of the hill. Apparently, it just beat Blur’s lines from ‘For Tomorrow’ into second place: “It’s windy there and the view’s so nice…”

The Cumberland Basin, home to the Feng Shang Princess Chinese restaurant (all North Londoners have been there once), used to extend further east, to the site that is now the London Zoo car park, and under Gloucester Gate. This part of the canal fell into disuse just before the Second World War and was filled in with rubble from the Blitz after it. If you’ve ever wondered why Gloucester Gate is a bridge over nothing, this is why – the canal used to pass below it.

Nestled in among the industrial warehouses close to Camden Lock, the Pirate Castle of 1977 looks like some kind of folly, a hangover from a party long since over, not least because its medieval castellations and Jolly Roger flag are supplemented by a huge sign branding it PIRATE CASTLE. It is, in fact, a boating and outdoor activities charity. It was something of a surprise to discover that it was designed by the normally rather serious modernist Richard Seifert, he of Stage 3 Lancaster Gate and Centrepoint fame.

Nestled in among the industrial warehouses close to Camden Lock, the Pirate Castle of 1977 looks like some kind of folly, a hangover from a party long since over, not least because its medieval castellations and Jolly Roger flag are supplemented by a huge sign branding it PIRATE CASTLE. It is, in fact, a boating and outdoor activities charity. It was something of a surprise to discover that it was designed by the normally rather serious modernist Richard Seifert, he of Stage 3 Lancaster Gate and Centrepoint fame.

The towpath crosses the Interchange Basin, known popularly as Dead Dog Hole, by a bridge dating from 1845 when the LNWR started planning its first interchange facility. The vent openings in the wall alongside the towpath serve the underground vaults built in 1854-6 west of the Interchange Basin which were formerly used for storing wine, beer and spirits (the Gilbey’s Gin warehouse was close by).

The red brick building now called the Interchange Warehouse was designed to straddle the interchange dock. The dock was bridged over with heavy girders supporting the railway tracks and platforms of a railway goods shed, and the barges and narrow boats below were accessed through trapdoors in the platforms.

Camden Market has been an institution for as long as I can remember, and it seems to have changed little – still lots of ethnic food, flowing drapes and exotic incense. How reassuring. A temporary market was first established here in 1974 and today it is one of the most popular visitor destinations in London, attracting approximately 100,000 people each weekend.

MTV Studios used to be the offices of TV-am, designed by Terry Farrell in 1982 and a fabulous expression of post-modernism. Shortly after its completion, critic Jonathan Glancey called it “one of the most obviously spectacular architect-designed interiors completed in recent years and one of the high points of Postmodernism”. Today, the project could be seen as an early precursor to the playful workplaces of technology companies likes Google and Facebook. Clive Wilkinson, one of the architects behind the Googleplex, was actually among Farrell’s team. Sadly, much has been lost and it is a shadow of its former post-modern self. But the egg cups still straddle the roof-line!!

Just past Kentish Town Rd on the south side, squeezed in between Sainsbury’s and the canal, is Grand Union Walk, designed by Nicholas Grimshaw in 1988 and comprising a run of ten individual hi tech houses. There’s a fascinating film about the houses on You Tube in which Nicholas Grimshaw goes back for the first time and meets with a family that has lived there since it was built. The owner was asked what she liked about the place so much and she replies; “I love sci fi…it looked like a space hub.” They are in fact that very rare thing, a modern terrace, bringing an industrial aesthetic to a residential setting. If they remind you slightly of the sides of a London bus, that’s not a coincidence, that was the panelling they used.

When the canal was used for commercial purposes, living by its side would have been considered undesirable. But since the demise of the commercial use of the canal in the 1960s this has steadily changed, and canal side properties today have a premium of up to 30% vs their immediate neighbours.

The next stage of the trip lacks a thrill a minute, but I was amused on researching about an ugly brown building on the south bank at St Pancras Way to discover that its official postal address is in fact ‘The Ugly Brown Building, 6a St Pancras Way’ and, irony of ironies, it is owned by the very design-conscious Ted Baker clothing retailer. But they can’t be held responsible for having built it – that was our trusted Royal Mail, the organisation that built beautifully until the mid-20th-century and then generally built rubbish.

But ultimately a building comes down to how well it works for the purpose. As Ludwig Wittgenstein, put it: “The meaning lies in the use.” We shortly see two buildings – the Francis Crick Institute and the British Library – where the building’s design is a vital factor in determining how knowledge is accessed and developed through team interaction.

For those of you who have done the whole circle in a day, or who are now completing the whole circle for the first time, excitement mounts as you realise you are getting back to where it all begun 10 or so hours ago; or it could be a few days or many months since you set out.

Staying on the canal (quicker)

Several more things to see this way if you stay on the canal as far as The Granary Square Plaza Bridge…

Firstly, the rather splendid Gasholder Park. The gasholders were constructed in the 1850s as part of the Pancras Gasworks and remained in use until 2000. When the redevelopment began, the cast iron structure was dismantled piece by piece, painstakingly restored and moved to its new home here, on the north of the canal. The circular lawn inside is a unique and relaxing green space.

Firstly, the rather splendid Gasholder Park. The gasholders were constructed in the 1850s as part of the Pancras Gasworks and remained in use until 2000. When the redevelopment began, the cast iron structure was dismantled piece by piece, painstakingly restored and moved to its new home here, on the north of the canal. The circular lawn inside is a unique and relaxing green space.

Secondly, a new pedestrian bridge was opened in 2017, known as Somers Town Bridge. It takes off just south of Gasholder Park and land on the north end of Camley St Natural Park.

Secondly, a new pedestrian bridge was opened in 2017, known as Somers Town Bridge. It takes off just south of Gasholder Park and land on the north end of Camley St Natural Park.

Then, the delightful; Pancras Lock, with an immaculately kept lock keeper’s garden:

Finally, on your left again, you will see the Coal Drops Yards, built in the 1850s, for receiving and sorting coal as it arrived from the north of England by train. Now the Victorian brick arches are being brought back to life in a design from Heatherwick Studios that combines industrial heritage with contemporary architecture, including a somewhat controversial ‘kissing’ roof connecting the two coal drops. It will be a shopping quarter, with a focus on fashion, craft and culture, intended to compete with Covent Garden.

My preferred route back to King’s Cross

It’s hard to drag oneself away from the canal, but there’s so much to see this way, I recommend it…

Cross Somers Town Bridge and you will reach the Camley St Natural Park (0.8 hectares, 2 acres), a tiny urban nature reserve. It was created from an Old Coal Yard in 1984 and was the first artificially created park in the country to gain statutory designation as a local nature reserve, and soon after that survived the threat of redevelopment. It provides a home for birds, butterflies, bats and a wide variety of plant life; and a fabulous break to us humans from the bustle of the cityscape.

Cross Somers Town Bridge and you will reach the Camley St Natural Park (0.8 hectares, 2 acres), a tiny urban nature reserve. It was created from an Old Coal Yard in 1984 and was the first artificially created park in the country to gain statutory designation as a local nature reserve, and soon after that survived the threat of redevelopment. It provides a home for birds, butterflies, bats and a wide variety of plant life; and a fabulous break to us humans from the bustle of the cityscape.

There is so much of interest to be found in St Pancras Gardens, including the extravagant B

There is so much of interest to be found in St Pancras Gardens, including the extravagant B urdett-Coutts memorial sundial, the Hardy tree encircled by tombstones, an ancient church and the famous memorial to Sir John Soane’s wife, the design of which inspired the classic ‘K2’ Gilbert Scott red telephone box. And the church is believed to be one of the oldest in London, dating back to the 7th century. Coming out of the gardens, we looked across the road at Cecil Rhodes House, which is part of the Goldington St Estate; it’s rather an attractive building built in 1953, once again in the ‘streamlime moderne’ style.

urdett-Coutts memorial sundial, the Hardy tree encircled by tombstones, an ancient church and the famous memorial to Sir John Soane’s wife, the design of which inspired the classic ‘K2’ Gilbert Scott red telephone box. And the church is believed to be one of the oldest in London, dating back to the 7th century. Coming out of the gardens, we looked across the road at Cecil Rhodes House, which is part of the Goldington St Estate; it’s rather an attractive building built in 1953, once again in the ‘streamlime moderne’ style.

The Francis Crick Institute (formerly the UK Centre for Medical Research and Innovation) is a biomedical research centre, opened in 2016. It’s a partnership between Cancer Research UK, Imperial College London, King’s College London, the Medical Research Council, University College London and the Wellcome Trust. It will have 1,500 staff, including 1,250 scientists, and an annual budget of over £100 million, making it the biggest single biomedical laboratory in Europe. Labs within the building are arranged over four floors, made up of four interconnected blocks, designed to encourage interaction between scientists working in different research fields. The institute also includes a public exhibition/gallery space, an educational space, a 450-seat auditorium and a community facility.

The Francis Crick Institute (formerly the UK Centre for Medical Research and Innovation) is a biomedical research centre, opened in 2016. It’s a partnership between Cancer Research UK, Imperial College London, King’s College London, the Medical Research Council, University College London and the Wellcome Trust. It will have 1,500 staff, including 1,250 scientists, and an annual budget of over £100 million, making it the biggest single biomedical laboratory in Europe. Labs within the building are arranged over four floors, made up of four interconnected blocks, designed to encourage interaction between scientists working in different research fields. The institute also includes a public exhibition/gallery space, an educational space, a 450-seat auditorium and a community facility.

Oh yes, and from here you get a good view of the British Library, one of my favourite building in the world. Such a beautiful place, but it took so long to build. Designed by architect Sir Colin St John Wilson between 1982 and 1999, it was the largest UK public building to be built in the 20th century and is already Grade I listed.

Fiona Macarthy wrote about it well in the Guardian; “Is this a factory or is it a temple? A library needs to be a bit of both. The approach from Euston Road through the temple-like main portico across the piazza with its little built-in amphitheatre focuses the mind. Wilson’s ideal libraries were always places redolent of intellectual continuity, alive with “the buzz of scholars of the past”, and the walk across the courtyard evokes a corresponding buzz of previous architects: the 19th-century English Free School exemplified by Butterfield, Street, Waterhouse and George Gilbert Scott, whose red-brick St Pancras Chambers, exactly matched by the brickwork of the library, is so close at hand; and the 20th-century organic modernists Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto and Hans Scharoun. The clock tower pays a subtle homage to WM Dudok’s town hall in Hilversum, admired by all young architects of Wilson’s generation.” For the record, Prince Charles described the Reading Room as looking “more like the assembly hall of an academy for secret police”.

Fiona Macarthy wrote about it well in the Guardian; “Is this a factory or is it a temple? A library needs to be a bit of both. The approach from Euston Road through the temple-like main portico across the piazza with its little built-in amphitheatre focuses the mind. Wilson’s ideal libraries were always places redolent of intellectual continuity, alive with “the buzz of scholars of the past”, and the walk across the courtyard evokes a corresponding buzz of previous architects: the 19th-century English Free School exemplified by Butterfield, Street, Waterhouse and George Gilbert Scott, whose red-brick St Pancras Chambers, exactly matched by the brickwork of the library, is so close at hand; and the 20th-century organic modernists Frank Lloyd Wright, Alvar Aalto and Hans Scharoun. The clock tower pays a subtle homage to WM Dudok’s town hall in Hilversum, admired by all young architects of Wilson’s generation.” For the record, Prince Charles described the Reading Room as looking “more like the assembly hall of an academy for secret police”.

And then, finally, I suppose, that greatest building of all, St Pancras Station, a wondrous piece of Victorian Gothic revival architecture designed by George Gilbert Scott and constructed in 1868; and the train shed, completed in 1868 by the engineer William Henry Barlow, the largest single-span structure built up to that time. I have loved St Pancras ever since I was a child and regularly passed it on my way to see my uncle. And to think it nearly got knocked down. Thank you, John Betjeman, for helping save it (you will find a statue of him in the concourse). One slight criticism though. Whilst functional, I feel it has been sliced and diced in a slightly unfortunate way internally, meaning crowded thoroughfares and very little elegant open space.

And why is it you have to walk up a slope to get to the main entrance of St Pancras? Had St Pancras been built level with its immediate terrain the tracks would have had to go up and over the canal. So, the platform and tracks were built up on arches and thus could cross the canal without a climb (unlike King’s Cross, which goes into a tunnel under the canal).

And why is it you have to walk up a slope to get to the main entrance of St Pancras? Had St Pancras been built level with its immediate terrain the tracks would have had to go up and over the canal. So, the platform and tracks were built up on arches and thus could cross the canal without a climb (unlike King’s Cross, which goes into a tunnel under the canal).

Back to where we started, Battle Bridge Place, the point where there was an ancient crossing of the Fleet and scene of a fierce battle between Boadicea and the Romans; today, it’s yards away from the European headquarters of Google, major players in the world’s information superhighway.

So, there you have it; we set out in the horse and carriage age (the mews), progressed through canals and railways, went under the Westway and have ended up on the information highway – truly a journey about the history of transport and communication.

THE ROUTE

- Set out up Westbourne St and take the first right into Bathurst St, then the first left into Bathurst Mews, which you follow until you come out in Sussex Place

- On reaching Sussex Place head N, crossing Sussex Gardens, with Norfolk Sq on your right, crossing Praed St to reach Paddington Station

- Turn right just after the station along Winsland Mews, turning right at the end down Winsland St (pedestrian only); turn left on reaching Praed St and follow it all the way along until just past the Post Office and level with Sale Place, at which point you turn L into Paddington Basin

- Follow the Basin W, across the Fan Bridge, then along the northern side, eventually over the Station Bridge, then walking N along the canal

- Just after the Bishop’s Bridge Rd, veer left through Sheldon Square, and then back again to the canal and under the Westway, following the canal all the way into Little Venice until you reach the Westbourne Terrace Bridge

- From Westbourne Terrace Bridge, follow the north side of the canal along Blomfield Rd, having to go on the pavement at one stage, until you reach the tunnel; at this point you cross the Edgeware Rd, continue along Aberdeen Place and at the end, just past Crocker’s Folly, take a narrow passage straight ahead, which eventually brings you out onto Lisson Grove

- Cross over on reaching Lisson Grove and rejoin the canal path on the north side; if this happens to be closed, then follow along on the S side instead and cross over at the pedestrian bridge to rejoin the north side; then continue along the north side, entering Regent’s Park, passing the grand classical homes on the other bank and then coming off at the first bridge in the park, Charlbert Bridge

- Cross Charlbert Bridge and head S into Regent’s Park, heading for the boating lake; swing round to the left as you reach the boating lake and cross over the bridge to reach the Rose Gardens; then head back along the eastern end of the lake, heading toward the zoo

- On reaching the zoo, head W along its S side to cross Primrose Hill Bridge, then over the road into Primrose Hill; then keep to the left of the hill, heading steadily up and taking the second right to the high point

- From the high point, head down the hill to the SE exit; cross the road, head W to the end of St Mark’s Church, then take the path down to the Regent’s Canal Towpath marked by a blue sign, heading under the road, then N along the canal; follow the canal path, crossing the roving bridge at Camden Market to reach Camden High St

- Rejoin the N side of the canal at Camden High St and continue heading E, past Gasholder Park, climbing a gradient alongside the canal just before St Pancras Lock until you are level with the new pedestrian Somers Town Bridge crossing the canal; head over this bridge past the Camley St Nature Reserve

- From here, head right up Camley St, to the entrance to St Pancras Gardens, which is in a brick wall on your left; head through the gardens, taking in the various sights, before exiting W into Goldington Crescent

- From here take a left turn down Goldington St, then Purchase St, turning left into Brill Place, then right into Midland Rd, with St Pancras on your left and the Francis Crick Institute on your right

- On reaching the Euston Rd, turn left, walk up the raised forecourt of St Pancras to inspect the main entrance, then down the steps the other side, across Pancras Rd and then left to return to Battle Bridge Place.

PIT STOPS

Bathurst Deli, 3 Bathurst St, W2 2SD (020 7262 1888). Maybe a bit close to the start of the walk, but you never know how you’ll be feeling…

Waterside Café, in Browning Pool – you will not get a better spot than this. (020 7266 1066) Sit on board in inclement weather, or on the canal side when its sunny. Delightful location

Café Laville, 453 Edgware Rd, W2 1TH (020 7706 2620) is built over the western entrance to the Maida Hill Tunnel, and has great views along the canal.

The Hub (0300 061 2324) is located in the middle of Regent’s Park’s busy playing fields. It could, I suppose, be mistaken for a modern bus station, but it has a certain style and great views.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Regent’s Park Rd, Primrose Hill (NW1 8XP) this is the epitome of the ‘indie’ high street, with achingly stylish shops that every city village would like to have. Lots of places to eat and drink too.

Camden Market (NW1 8NH) The biggest and the original. Over 1,000 shops and stalls selling fashion, music, art and food next to Camden Lock.

Coal Drops Yard (N1C 4AB), opening 2018, with a focus on fashion, craft and culture

PLACES TO VISIT & THINGS TO DO

Hyde Park Stables (020 7723 2813, www.hydeparkstables.com) and Ross Nye Stables (020 7262 3791, www.rossnyestables.co.uk), both located in Bathurst Mews, offer rides out into Hyde Park for any and all abilities.

Alexander Fleming Museum, St Mary’s Paddington, Praed St, London W2 1NY (020 7886 6528,) 10am-1pm Mon-Thu (check times) The actual lab where penicillin was discovered.

The Regent’s Park Boating (0207 724 4069) The boating lake is open daily from 10:30 am – 6:00 pm from April through to the end of October and offers rowing boats and adult pedalos for hire.

London Zoo, Regent’s Park (www.zsl.org/zsl-london-zoo ) One of the greatest zoos in the world.

Camley Street Natural Park, 12 Camley St, N1C 4PW (020 7833 2311, ) A beautiful backwater of green amidst the clamour of regeneration. Pause a while and slow down.

FURTHER EXPLORATION

Watch: A very cool walking video: http://www.paddingtoncentral.com/article/walk-way

Follow: the Paddington Public art trail at http://www.thisispaddington.com/cms/files/downloads/Paddington_PublicArtTrail.pdf

Watch: Barging Through London (Again) by Somewhere shows Harry Parkinson’s rare original film (made as part of the ‘Wonderful London’ series in 1924) side-by-side with Somewhere’s 2011 shot-for-shot remake. Agree with this feedback: “This is quite lovely; I’ve made this trip many times by bike and then on my boat. Fantastic that you have gone to the trouble of identifying all the locations and situating these alongside the original footage. This is definitely a ‘city symphony’.”

Leave a Reply