Bridges, green spaces and regeneration

The early English name for Bristol was ‘Brycgstow’, the place of the bridge, and this walk explores that idea a little further – in all we cross, pass or see nineteen bridges! Telling you a lot about the topography of Bristol and taking you through big green spaces and major regeneration programmes.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 9.9 km (6.2 miles)

- Typical time: 2 ½ hours

- Height change: 65 metres

- Start & Finish: Bristol Temple Meads (BS1 6EA)

- Terrain: Straightforward; sturdy footwear recommended

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Sparke Evans Park, Arnos Vale Cemetery, Perrett’s Park, Victoria Park, Somerset Square, Quaker Burial Ground, Queen Square, Castle Park, Temple Quay Square |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Avon, Floating Harbour, Welsh Back, River Frome |

| Stunning cityscape | Perrett’s Park, Redcliffe Parade |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | St. Mary Redcliffe (from the 12th C), Queen Square (1700s), Llandoger Trow pub (1664), Bristol Castle remains (11th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Entrance lodges and Mortuary chapels at Arnos Grove (1840s) Fry’s House of Mercy (1784), Redcliffe Parade (1760s), Theatre Royal (1766), The Exchange (1743), St Nicholas Church (1760s), Old Council House (1827), Christchurch (1791) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Bristol Temple Meads (1840 onwards), The General Hospital (1853), Robinson’s Oil Seed Mill (1875), WCA Warehouse (1909), The Granary (1869), Market Hall (1848), The West of England Bank (1857) , Grand Hotel (1865) |

| Industrial Heritage | Floating Harbour, Bristol Harbour Railway, Finzel’s Sugar Refinery, Georges Bristol Brewery Sheldon Bush lead shot tower |

| Modern (post-1918) | Sheldon Bush lead shot tower |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Kate’s Kitchen at Arnos Vale Café,

Mrs Brown’s Café, Victoria Park, Small Street Espresso, Edna’s Kitchen, Castle Park |

| Quirky Shopping | St Nicholas Market |

| Places to visit | St Mary Redcliffe Church, Redcliffe Caves, M Shed |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Picnic in the Park, Perrett’s Park (Aug)

Bristol Food Connections festival (early may) Get Growing Garden Trail (June) Victoria Park: Art on the Hill Arts Trail (October) |

City population: 449,300 (2017 est.)

Urban population: 617,000 (2011 census)

Ranking: 10th largest city in the UK (Wiki)

Date of origin: 11th century

‘Type’ of city: Maritime

City status: granted in 1542, when the Diocese of Bristol was founded

Some famous inhabitants of Redcliffe, Old Town & Temple Meads: William Watts (inventor), Billy Butlin (St Mary’s Radcliffe School), Samuel Plimsoll (1824-1898, social reformer, b. Colston Parade), John Cabot (explorer), Woodes Rogers (1679 – 1732, sea captain and privateer, Queen Square)

Notable city architects/planners: William Bruce Gingell (1819 – 1899) – influential in the Bristol Byzantine style, notably Gardiners Warehouse, Lloyds Bank, Robinson’s Warehouse; also, the General Hospital

Number of listed buildings (the whole of Bristol): 4,600 listed, of which 100 are Grade I and 212 Grade II*

Films shot here: These Foolish Things (2005, King St), Starter for Ten (2006, Temple Meads & Floating Harbour), The Duchess (2008, Bristol Old Vic). There is a very useful set of movie maps at; http://www.filmbristol.co.uk/bristol-movie-maps

TV series shot here: Skins (Somerset Square), Sherlock (Arnos Grove, Queen Square, King St), see http://www.filmbristol.co.uk/content/files/Final%20sherlock.pdf), Doctor Who (Corn St, Waring House), Being Human (Redcliffe Caves, General Hospital, St Nicholas Market, Temple Meads), Only Fools & Horses (Welsh Back), The Young Ones (Temple Meads)

Estimated % of green space in the city (Eski): 29% (3rd out of Top 10 cities)

THE CONTEXT

Above all this walk is about the burgeoning growth and prosperity of Bristol – from the beginnings in the Old Town around Bristol Bridge, through the vast wealth of the merchant buccaneers epitomised by Queen Square and the Floating Harbour to the economic development of the Victorian age – the train opening up communications with the rest of the country and the parks and cemeteries starting to serve a rapidly expanding population; and in more recent years, the massive new wave of regeneration emanating from the Temple Meads Development Plan.

Sir John Summerson, one of the leading British architectural historians of the 20th century, wrote; “If I had to show a foreigner one English city and one only, to give him a balanced idea of English architecture, I should take him to…Bristol, which has developed in all directions, and where nearly everything has happened.” And if he had had to pick a single walk in Bristol to go on with his visiting friend, he could have done worse than to pick this one.

In more practical terms, this is a walk about crossing three critical transport modes – water, rail and road – and the naturally hilly terrain either side of the Avon that gives Bristol such a distinctive and appealing character. Incredibly, our walk takes us over (5), under (4), past (7) and within view of (13) nineteen bridges in all, which is something of a record for our urban rambles.

These are they:

- Temple Meads Viaduct (1840) (under)

- Brock’s Bridge (2017) (past)

- Albert Rd Viaduct (1840s) (under)

- Totterdown Bridge (1888) (past)

- Sparke Evans Suspension Bridge (1900s?) (over)

- St Philips Causeway Bridge (early 1990s) (view of…)

- Clifton Suspension Bridge (1864) (view of, admittedly in the far distance)

- St Luke’s Rd Railway Bridge (1840s) (under)

- The Banana Bridge (1890) (over)

- Redcliffe Bascule Bridge (1942) (view of…)

- Bathurst Basin Footbridge (1970s) (over)

- Prince St Bridge (1942) (over)

- Pero’s Bridge (1999) (past)

- Bristol Bridge (1769, replacing a 12C bridge) (past)

- Leonard Lane Bridge (1900s) (under)

- Castle Bridge (2017) (over)

- St Philips Bridge (replacing an 1841 bridge destroyed by the Blitz) (past)

- Temple Way Bridge (1930s) (past)

- Valentine’s Bridge (2000) (past)

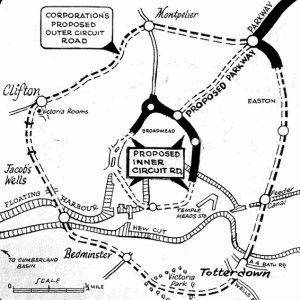

But there’s one fly in the ointment I didn’t mention yet. We love the rivers, we love the railways, we love the contours, but in the 1960s the road system threatened to irreversibly destroy the landscape we are planning to walk through. And it partly did – in the ‘Tragedy of Totterdown’ more than 500 houses were bulldozed in the 1960s to make way for the ‘Outer Circuit Road’ designed to relieve traffic congestion.

The full horror of the plan can see in the diagram left. Notice how it would have sliced through the middle of Victoria Park. Green space often tends to be an easy victim for road ‘improvers’, as trees and blades of grass can’t form protest groups (mind you, protesters often camp out in trees). Thankfully Britain’s slowness to get things done meant attitudes had time to change, and in the 1970s the whole scheme was put on hold. Reversed even. Later in the walk, we will experience the ‘Miracle of Queen Square’, where this classic Georgian square was rescued from the Inner Circuit Road, which for three decades had thundered straight through it. How mad we were.

The full horror of the plan can see in the diagram left. Notice how it would have sliced through the middle of Victoria Park. Green space often tends to be an easy victim for road ‘improvers’, as trees and blades of grass can’t form protest groups (mind you, protesters often camp out in trees). Thankfully Britain’s slowness to get things done meant attitudes had time to change, and in the 1970s the whole scheme was put on hold. Reversed even. Later in the walk, we will experience the ‘Miracle of Queen Square’, where this classic Georgian square was rescued from the Inner Circuit Road, which for three decades had thundered straight through it. How mad we were.

Things really are better today. To celebrate Bristol being the Green Capital of Europe in 2015 a plan was drawn up to connect all the City’s Green spaces together with popular routes. Tree-lined routes are intended to link one open space to another. The open spaces include parks, playing fields, cemeteries, allotments, golf courses, public footpaths and bridleways, harbourside and riverside sections as well as numerous small fragments which hardly feature on any records but could have an invaluable visual role in popularising these routes. You can see the full Bristol Greenway project at http://www.johngrimshawassociates.co.uk/downloads/GreenCapital.pdf

Our walk has the same intention.

THE WALK

We started our walk at one of Bristol’s best-known landmarks, Bristol Temple Meads station, originally built by the man so associated with Bristol, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He designed the Bristol terminus of the new Great Western Railway, completed in 1840, in a 15th-century style, with flat arches and a hammer beam roof, fronted by offices in the Tudor style. This is the building on the right as you walk down Station Approach, called the ‘Engine Shed’, currently a space where entrepreneurs, business leaders, academics, students and corporates can collaborate.

The main building out of which we came off our train was in fact built in the 1870s by Brunel’s former associate Matthew Digby Wyatt and is in the Victorian Gothic style. This is the image most people have when they think of the station.

The main building out of which we came off our train was in fact built in the 1870s by Brunel’s former associate Matthew Digby Wyatt and is in the Victorian Gothic style. This is the image most people have when they think of the station.

As soon as we emerged from under the viaduct we came into an area of feverish building activity. This is the epicentre of the Temple Quarter Enterprise Zone, designed to drive local growth and create jobs.

On the left side of Cattle Market Rd is the site of the future £300 million University of Bristol’s Temple Quarter Campus. It is replacing an empty sorting office building, formerly operated by Royal Mail but derelict since 1997. The campus, which will include a new business school, digital research facilities and a student village, is expected to open in 2021 and accommodate up to 5,000 students.

To the right, there is a major new bridge constructed over the River Avon. This provides access to the Bristol Arena, the flagship project in the Enterprise Zone. It is due to be completed in 2020 and will be a 12,000-seater venue for events and concerts. The bridge is called Brock’s Bridge, named after William Brock (1830–1907), a local builder and entrepreneur who started a successful factory next to Temple Meads station and was also involved in the construction of St Philip’s Bridge, the Bristol Bridge and Bedminster Bridge.

From here, we go through a fairly narrow gap between the two waters onto what is effectively an island, bounded by the River Avon on the south and the Feeder channel on the north, which supplies water to the Floating Harbour from a link with the River Avon further upstream.

This area is called St Philip’s Marsh and is today an unappealing mishmash of retail parks and unplanned warehouses etc. It had been an industrial area with a vibrant community of around 6,000 people up until the 1950s, but sadly then the council decided to demolish all the houses and moved the residents to other areas as part of a ‘slum clearance’ program. Today there is very little housing in the area.

As Albert Rd twists round to the east, so we get a great view south of the coloured houses of Totterdown. Bristol is famous for its rows of colourful houses, but no-one seems to be exactly sure when and why the fashion started; it seems to be a vernacular common to seaside towns, perhaps introduced from foreign climes which were familiar to Bristolians through their global trade links. In the Mediterranean, for example, it is said that local fishermen used to paint their homes in bright colours in order to delimit properties and make them more visible from the sea.

As Albert Rd twists round to the east, so we get a great view south of the coloured houses of Totterdown. Bristol is famous for its rows of colourful houses, but no-one seems to be exactly sure when and why the fashion started; it seems to be a vernacular common to seaside towns, perhaps introduced from foreign climes which were familiar to Bristolians through their global trade links. In the Mediterranean, for example, it is said that local fishermen used to paint their homes in bright colours in order to delimit properties and make them more visible from the sea.

Anyhow, in Bristol it is now ‘encouraged’, and a campaign called Bristol Colour Capital has begun to get more homeowners to paint their house fronts to turn the city into a rainbow of colour.

“The city is already halfway there with many amazing coloured streets to be found, and increasing these would show off Bristol’s reputation for fun, creativity and self-expression,” according to the Bristol Colour Capital website.

I love some of the campaign’s reasons as to why the initiative is such a good idea:

- Make us happier and reduce crime – unsurprisingly, studies have shown that colour can make us feel good, feel inspired and feel safer.

- Tourism – Pretty, photogenic places draw more visitors. There could be colour maps, walking trails, exhibitions and much more.

- It brilliantly contrasts with Bath – which is all about one single colour, creamy Bath stone. Bristol’s full-colour palette is the exact opposite – each approach with its own appeal and beautifully complementary.

Happiness, added wealth and outsmarting the older, prettier sibling – what could be more compelling!?

The lack of a local community these days rather explains why Sparke Evans Park (2.9 hectares, 7.2 acres) feels so disembodied. It dates back to 1902, laid out on land presented to the Bristol Corporation by Sparke Evans and Jonathan Evans, local tannery owners. It was intended as a ‘green lung’ for the many families who lived and worked in the immediate vicinity at the time. The park’s roses were especially notable because the level of soot from industry and railways locally helped to keep them pest-free. But the factories and homes are now long gone and the park has a rather forlorn, ‘why here’ feel about it.

Then across the Sparke Evans Bridge, built by David Rowell & Co. painted yellow which seems to be a favourite colour for Bristol bridges. On the right is the massive

Then across the Sparke Evans Bridge, built by David Rowell & Co. painted yellow which seems to be a favourite colour for Bristol bridges. On the right is the massive  Paintworks, which describes itself as Bristol’s ‘creative quarter’ incorporating 11 live/work units, 210 houses and apartments and 6,700sqm commercial space. I rather like their description of themselves; “Paintworks is a bit of town, not a development. It’s a place where people want to work and a place they want to live. Not all that complicated really, but not many places are like it.”

Paintworks, which describes itself as Bristol’s ‘creative quarter’ incorporating 11 live/work units, 210 houses and apartments and 6,700sqm commercial space. I rather like their description of themselves; “Paintworks is a bit of town, not a development. It’s a place where people want to work and a place they want to live. Not all that complicated really, but not many places are like it.”

Entering Arnos Vale Cemetery (18.2 hectares, 45 acres) feels like entering a stately home, with its classically-inspired entrance lodges with their Doric columns which have a tunnel connecting them so the staff would not have to disrupt arriving funeral corteges. We half expected to be stopped by an enthusiastic National Trust volunteer soliciting us to take out an annual membership.

The cemetery was established in 1837 in response to the dangerous overcrowding of inner-city churchyards and was designed to be visually attractive in the style of a walled Greek Necropolis, with neoclassical mortuary chapels set in a beautiful garden of trees and plants noted in classical legend.

The cemetery was established in 1837 in response to the dangerous overcrowding of inner-city churchyards and was designed to be visually attractive in the style of a walled Greek Necropolis, with neoclassical mortuary chapels set in a beautiful garden of trees and plants noted in classical legend.

But in the 20th century, it fell into disrepair, and local groups began campaigning for its restoration. In 2003 it was featured on the BBC programme Restoration and has subsequently received a £4.8 million Heritage Lottery Fund grant. The volunteers are doing a fabulous job keeping the place open, looked after, loved and visited, so anything you can do to help this magical spot survive…

Today, the cemetery is also of considerable ecological importance, having progressed from mediaeval countryside to Georgian estate to Victorian Cemetery to the present day with almost no use of chemical pesticides or insecticides, helping make it a rare urban haven for wildlife and plants. David Goode in his seminal work ‘nature in Towns and Cities remarked: “Arnos Grove was famous for its avenue of Irish yews along the Ceremonial Way and other specimen trees included Austrian pines, western red cedars and Himalayan cedar. This cemetery forms a natural amphitheatre on a hillside overlooking the city and the landscape is still one of the most spectacular of all the old cemeteries.”

There are four fine buildings within the Cemetery – the two Entrance Lodges that we have just seen and two Mortuary Chapels (Anglican and Nonconformist). All four buildings are listed Grade II*. Designed by Charles Underwood (who also built the Royal West of England Academy) and built using the finest materials so that the high quality of the building probably saved them from even greater dereliction, given their lack of maintenance and attention over the last two decades of the 20th century.

The names of many prominent Victorian and Edwardian families appear on elaborate memorials, such as ‘Wills’ and ‘Robinson’ who provided the generations of Bristol with much-needed employment in their heydeys. Great social reformers such as George Muller, Mary Carpenter and Raja Rammohun Roy rest in the Arcadian Garden area. Among the ‘ordinary’ citizens are survivors of the Charge of the Light Brigade, and a police officer murdered in Old Market whilst trying to intervene over the ill-treatment of a donkey.

We wended our way up the slope taking tiny paths here and there, at every turn gravestones or memorials celebrating Bristol citizens. You could while away many an afternoon imagining away the lives of others.

Coming out at the end of the cemetery we realised what a steep part of town we had reached. Apparently, Vale St, which a few hundred yards to our north, is the steepest street of houses in England. Feels a bit like San Francisco, especially the coloured houses.

Crowndale Road is a good example of an excellent Greenway Route connecting Arnos Vale to Perrett’s Park, lined as it is with trees and the houses having front gardens.

Crowndale Road is a good example of an excellent Greenway Route connecting Arnos Vale to Perrett’s Park, lined as it is with trees and the houses having front gardens.

We soon reach Perrett’s Park (6.7 hectares, 16 acres) laid out in 1929, on a steeply sloping site which forms a natural bowl. At the top of this bowl, a long terrace has been created, running along two sides of the park, laid out with rose beds and shrubberies, paved walkways and benches which command a fine view to the west and north. There is a plaque celebrating this most spectacular of views, taking in Dundry, Ashton Court, the Clifton Suspension Bridge, both of Bristol’s cathedrals and the Wills Memorial building.

Walking past the Perrett’s Park Allotments reminded us of how many allotments there are in Bristol and how committed the city is to self-sustainability. If you are interested in this subject, take a look at the Bristol Food Network, which ‘supports, informs and connects individuals, community projects, organisations and businesses who share a vision to transform Bristol into a sustainable food city’.

Walking past the Perrett’s Park Allotments reminded us of how many allotments there are in Bristol and how committed the city is to self-sustainability. If you are interested in this subject, take a look at the Bristol Food Network, which ‘supports, informs and connects individuals, community projects, organisations and businesses who share a vision to transform Bristol into a sustainable food city’.

Then down Ravenhill Rd to a rather ugly roundabout. Looking northeast along St John’s Lane we see that rather an odd sight for Bristol, a route that looks like a ‘new town’ boulevard, with raised green slopes on either side. Then, with a shudder, I realised what it was, the wider space bulldozed in preparation for a dual carriageway – the infamous Outer Circuit Road that thank God never was – this roundabout was the point where the dual carriageway would have thrust its way into Victoria Park – scary.

Then down Ravenhill Rd to a rather ugly roundabout. Looking northeast along St John’s Lane we see that rather an odd sight for Bristol, a route that looks like a ‘new town’ boulevard, with raised green slopes on either side. Then, with a shudder, I realised what it was, the wider space bulldozed in preparation for a dual carriageway – the infamous Outer Circuit Road that thank God never was – this roundabout was the point where the dual carriageway would have thrust its way into Victoria Park – scary.

Next, we head down to the absolutely wonderful Victoria Park (20.8 hectares, 51.5 acres). The park was established by the council in the 1880s following the expansion of Bedminster as a residential and industrial area within Bristol. By 1887, a children’s play area had been installed which became immediately popular. The streets around the park were laid out in 1891. By 1898, four rangers were permanently employed, and a bandstand had been installed. Several drinking fountains and a circular pond had also been established. This was (and is) truly a ‘people’s park’, designed from the start to be a ‘green lung’ to those people living locally who typically had no access to the countryside.

The Victoria Park Action Group was started in 2002 by people living near the park who wanted to preserve and improve its facilities. An example of just how important local support is to keeping ‘people’s parks’ just that…alive and kicking.

Toward the end of our route through the park, we saw the Water Maze (1984), modelled on the bosses on the roof of the church of St Mary Redcliffe, which we will see a little later. It was built over a 12th-century pipeline supplying water from a spring at Knowle to Redcliffe.

Toward the end of our route through the park, we saw the Water Maze (1984), modelled on the bosses on the roof of the church of St Mary Redcliffe, which we will see a little later. It was built over a 12th-century pipeline supplying water from a spring at Knowle to Redcliffe.

Langdon Street Bridge, more popularly called The Banana Bridge (the reason for the name will be fairly obvious if you go upstream a bit on the north side and view it side on), crosses the River Avon from York Road to Clarence Road. The footbridge was erected in 1883 as a temporary bridge on the site where Bedminster Bridge now stands. It was then transported here on barges at high tide. Love this 2017 article entitled The 11 oddest bridges in Bristol, take a look.

Redcliffe gets its name from the red sandstone on which it’s built – the steep cliff face can clearly be seen at the Addercliff, below Redcliffe Parade. For centuries, this “suburb” – home to many of Bristol’s rich merchant princes such as the Canynge family who moored their ships nearby – was as important as the city itself. But the Luftwaffe, slum clearance and road-widening have damaged it greatly and taken away much of the character of the place. But it is subject to a major regeneration programme that is improving it markedly and once again making it a fashionable place to live.

Built in 1756, Somerset Square was a fashionable square in Georgian times, albeit not in the same league as Queen Square which we pass through later. However, none of its original Georgian buildings have survived. One of the original houses was the town house of the Duke of Beaufort. In more recent times J.T. Francombe, Lord Mayor in 1920, lived here and was the custodian. Some houses were victims of the Blitz, but most were pulled down in the 1960s to make way for the present flats. Part of the southern area of the square was used in building St Mary Redcliffe & Temple School and Spencer House Flats. The fountain in the middle of the square is a mid to late-18th-century conduit head. It has Gothic trefoil arches which support eight plain columns, a cap and a large vase topped by a fir-cone.

Built in 1756, Somerset Square was a fashionable square in Georgian times, albeit not in the same league as Queen Square which we pass through later. However, none of its original Georgian buildings have survived. One of the original houses was the town house of the Duke of Beaufort. In more recent times J.T. Francombe, Lord Mayor in 1920, lived here and was the custodian. Some houses were victims of the Blitz, but most were pulled down in the 1960s to make way for the present flats. Part of the southern area of the square was used in building St Mary Redcliffe & Temple School and Spencer House Flats. The fountain in the middle of the square is a mid to late-18th-century conduit head. It has Gothic trefoil arches which support eight plain columns, a cap and a large vase topped by a fir-cone.

The Ship Inn feels like that increasingly endangered species, the proper boozer – it’s the sort of pub you want to stop at regardless of the time of day.

Tucked away in Colston Parade which runs along the side of the church, among a row of 18th- and 19th-century houses, is Fry’s House of Mercy, a small neo-Gothic building of 1784. It was endowed by William Fry, a local distiller, to house 12 widows.

St. Mary Redcliffe was constructed from the 12th to the 15th centuries, and Queen Elizabeth I famously described it as “the fairest, goodliest, and most famous parish church in England.” You will find a superb collection of carved bosses, elegant 18th-century ironwork, beautiful stained glass and a world-famous organ there.

The church, being alongside the harbour, was originally at the very centre of shipping and industry, which is the key to its history. The merchants of the Port of Bristol began and ended their voyages at the shrine of Our Lady of Redcliffe.

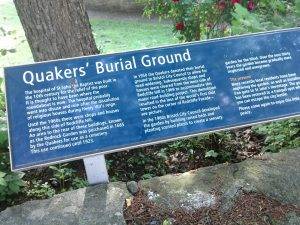

The Quaker Burial Ground by Redcliffe Way, just as you come across the pedestrian crossing, was used as their burial ground for a number of years.

The Quaker Burial Ground by Redcliffe Way, just as you come across the pedestrian crossing, was used as their burial ground for a number of years.

Going up the hill, we soon reached the spot where the Redcliffe Shot Tower should have been –tragically demolished in the 1960s for road widening and a new pub (The Coliseum, which is still there today). The shot manufacture transferred to the new Cheese Lane Shot Tower on the banks of the Floating Harbour, which we get to see later.

In 1775, William Watts, a plumber, started converting his house into the world’s first shot tower, in order to make lead shot by his innovative tower process. He did this by adding a tower atop his house, and by excavating a shaft into the soft sandstone below, achieving a total drop of around 90 ft. By 1782, the tower was complete and in production, and Watts was granted a patent on his process, which involved pouring molten lead through a perforated zinc pan into water below. It made him very wealthy and renowned, as recorded in this 19th-century ditty that first appeared in the Bristol Mirror –

Mr. Watts very soon a patent got,

So that only himself could make Patent Shot,

And King George and his son declared they’d not

Shoot with anything else – and they ordered a lot.

The Regent swore that the smallest spot

In a bird’s eye he’d surely dot:

And every sportsman, both sober and sot,

From the peer in his hall to the hind in his cot,

Vowed that they cared not a single jot,

When the game was strong and the chase was hot,

For anything else than the Patent Shot.

Redcliffe Parade grants you some of the best views in Bristol. Most of the houses were built in the period 1768-1800 by wealthy merchants. One of the families living here was merchant Thomas King who traded palm oil, ivory and redwood. Many of his ships were built in the Sydenham Teast shipyards on Merchant’s Wharf just to the west, where our path takes us in a few minutes.

Redcliffe Parade grants you some of the best views in Bristol. Most of the houses were built in the period 1768-1800 by wealthy merchants. One of the families living here was merchant Thomas King who traded palm oil, ivory and redwood. Many of his ships were built in the Sydenham Teast shipyards on Merchant’s Wharf just to the west, where our path takes us in a few minutes.

From here you get a good view north up to the Redcliffe Bascule Bridge (1942). It’s a rarity that the bridge is raised for vessels today and the Control Room is now mostly used for art exhibitions. You also get great views to the north-west of the Wills Building and Cabot Tower. What a lovely spot. An interesting building just behind the bridge on the right bank is the three-bayed WCA Warehouse (1909), according to the Pevsner City Guide “a blend of gruff industrialism and Edwardian classicism and an early Bristol use of reinforced concrete frame with brick cladding’”.

The Ostrich is one of only a handful of traditional dockside pubs in Bristol, built around 1745. It was used by the sailors, shipyard and dockside workers and merchants who worked in the Port of Bristol. One of its walls has been partly knocked down so that you can see some of the caves under Redcliffe.

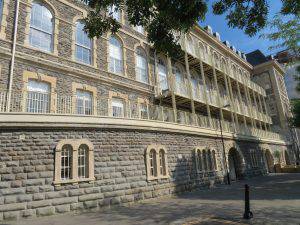

The General Hospital, on the east side of Bathurst Basin, was built in 1853 to take care of the casualties from the docks and the new factories at the time when Guinea Street was considered to be a healthy spot surrounded by water and overlooking country fields. The architect was WG Gingell, and the building makes a grand statement with its Italianate stonework and French Renaissance rooftops. It finally closed its doors in 2012 and has subsequently been converted into a commercial and residential development.

The General Hospital, on the east side of Bathurst Basin, was built in 1853 to take care of the casualties from the docks and the new factories at the time when Guinea Street was considered to be a healthy spot surrounded by water and overlooking country fields. The architect was WG Gingell, and the building makes a grand statement with its Italianate stonework and French Renaissance rooftops. It finally closed its doors in 2012 and has subsequently been converted into a commercial and residential development.

Then across Bathurst Basin Footbridge (late 1970s). People can be a bit disparaging about this bridge (‘It looks like one of those big tyre swings in an adventure playground’), but there’s an explanation for that. The company that wanted to re-develop Bathurst Quay was required to put a footbridge in but claimed it would make the overall scheme unviable. Then someone came up with the bright idea of using redundant steel dredging tubes from the harbour at about half the price quoted by the developer – and voila, you have the bridge you see today. An early example of waste recycling! It was the first new footbridge to be built reconnecting the important foot-route along the south shore and signalling the new leisure usage of the Floating Harbour.

Then across Bathurst Basin Footbridge (late 1970s). People can be a bit disparaging about this bridge (‘It looks like one of those big tyre swings in an adventure playground’), but there’s an explanation for that. The company that wanted to re-develop Bathurst Quay was required to put a footbridge in but claimed it would make the overall scheme unviable. Then someone came up with the bright idea of using redundant steel dredging tubes from the harbour at about half the price quoted by the developer – and voila, you have the bridge you see today. An early example of waste recycling! It was the first new footbridge to be built reconnecting the important foot-route along the south shore and signalling the new leisure usage of the Floating Harbour.

Just to the left as you cross the bridge is the quaint Bathurst Parade; and a very striking building is Robinson’s Oil Seed Mill built in 1875, also designed by WB Gingell in Gothic style. The facade of yellow brick is decorated in the Moorish manner with superb ornamentation and decorative ogee arches, extravagant perhaps in a warehouse but a delight to the eye.

Just to the left as you cross the bridge is the quaint Bathurst Parade; and a very striking building is Robinson’s Oil Seed Mill built in 1875, also designed by WB Gingell in Gothic style. The facade of yellow brick is decorated in the Moorish manner with superb ornamentation and decorative ogee arches, extravagant perhaps in a warehouse but a delight to the eye.

Now we head round the waterfront along Merchant’s Quay to the Prince St Bridge. The bridge was completed in 1879 and is a swing bridge, operated by water hydraulic power provided by the adjacent engine house and accumulator tower. It has been undergoing renovation for a long while, one of those cases where you start working on fixing something and then discover numerous other problems. And a campaign has now begun to try and prevent the bridge from being used by cars again.

Now we head round the waterfront along Merchant’s Quay to the Prince St Bridge. The bridge was completed in 1879 and is a swing bridge, operated by water hydraulic power provided by the adjacent engine house and accumulator tower. It has been undergoing renovation for a long while, one of those cases where you start working on fixing something and then discover numerous other problems. And a campaign has now begun to try and prevent the bridge from being used by cars again.

Then we kept skirting around the harbourside to Pero’s Bridge (1999), named in honour of Pero Jones, who came to live in Bristol as the slave of John Pinney. Composed of three spans, the outer two are fixed and the central section can be raised to allow tall boats to pass along the floating harbour. The most distinctive features of the bridge are the pair of horn-shaped sculptures which act as counterweights for the lifting section. The ‘love padlock’ lockers have been in action here.

Then we kept skirting around the harbourside to Pero’s Bridge (1999), named in honour of Pero Jones, who came to live in Bristol as the slave of John Pinney. Composed of three spans, the outer two are fixed and the central section can be raised to allow tall boats to pass along the floating harbour. The most distinctive features of the bridge are the pair of horn-shaped sculptures which act as counterweights for the lifting section. The ‘love padlock’ lockers have been in action here.

Queen Square (2.4 hectares, 5.9 acres) is an outstanding example of urban regeneration. The site on which the square was built lay outside Bristol’s city walls and was known as the Town Marsh. The Square was planned in 1699 and building finished in 1727. It was named in honour of Queen Anne and became the most sought after place to live in Bristol, but as Clifton was developed from the end of the 18th century and through the 19th century, it supplanted Queen Square.

When Bristol was swept by violent riots on 30 October 1831 (sparked when the House of Lords blocked the Reform Bill), nearly 100 of the buildings in and around the square, including the mayoral Mansion House, Bishop’s Palace and Custom House, were burned to the ground. Rebuilding took place over the next 80 years.

Worse was to come a century later. In 1937 the Inner Circuit Road was driven diagonally across the Square from SE to NW, leading to a steady decline in the quality of the environment. Until 1999 that is, when the City Council, supported by English Heritage and the Queen Square Residents Association, made a successful grant application to the Heritage Lottery Fund to restore the square as part of the fund’s Urban Parks Programme. The Square has now been restored to a high standard. The railings and forecourts of the surrounding buildings have been reinstated, and the central open space with its promenades and equestrian statue restored to their former grandeur. And other benefits have accrued – cycle usage quadrupled in a few years. What a truly fabulous restoration.

On King Street is the beautiful Theatre Royal of 1766, the oldest surviving theatre in England; and the famous Llandoger Trow pub of 1664. a pub in a 17th-century half-timbered building, one of the last remnants of this style of building in a city once renowned for its early architecture. The pub takes its name from the regular sailing barges that came from Llandoger in South Wales. Tradition has it that Daniel Defoe met Alexander Selkirk here and was inspired by his tales to write Robinson Crusoe. King St is a pleasure to walk along, described in the Pevsner Guide as “perhaps the most rewarding street in Bristol both for its gently curving composition and harmonious juxtaposition of 350 years of buildings.”

Turning right into Charlotte St and then left back into Little King St, we wanted to go past another fabulous piece of Byzantine, The Granary (1869), now Loch Fyne on the ground floor. It was a grain store, built by Ponton & Gough and in my mind is the very best example of the Bristol Byzantine style.

‘Bristol Byzantine’ came about in the mid to late nineteenth century and was generally used for industrial buildings and warehouses. The style may have originated when William Venn Gough and Archibald Ponton met John Addington Symonds, a Bristol-born historian of the Italian Renaissance. Some believe the name was coined by the architectural historian Sir John Summerson.

The style is heavily influenced by Byzantine and Moorish architecture from buildings in Venice and Istanbul. Or think the Mezquita in Cordoba in Spain. Windows often have arched tops and are aligned in vertical columns on stories above the ground floor; and brickwork is often polychromatic (multicoloured), sourced from the nearby Cattybrook brickworks.

The style is heavily influenced by Byzantine and Moorish architecture from buildings in Venice and Istanbul. Or think the Mezquita in Cordoba in Spain. Windows often have arched tops and are aligned in vertical columns on stories above the ground floor; and brickwork is often polychromatic (multicoloured), sourced from the nearby Cattybrook brickworks.

So why is this stretch of water in front of us called the Welsh Back? Well, Back because they were once literally the backs of merchants’ houses from where goods were loaded directly onto ships. And Welsh because vessels from Wales frequented this stretch of water. Simple really.

The Merchant Navy Memorial on the quayside further up Welsh Back, unveiled by Princess Anne in 2001 provides a place for peaceful reflection on the debt we owe to all those lost at sea in times of peace and war. My uncle Brian was in the Merchant Navy and ‘crossed the bar’ in the Second World war, so I paused to reflect on his great sacrifice. The inscription etched in bronze reads: “In war and peace they plied their trade, over the angry seas, remember them as here you stand beneath these placid trees”. Another poignant reminder of the myriad seafaring associations of the city.

The Merchant Navy Memorial on the quayside further up Welsh Back, unveiled by Princess Anne in 2001 provides a place for peaceful reflection on the debt we owe to all those lost at sea in times of peace and war. My uncle Brian was in the Merchant Navy and ‘crossed the bar’ in the Second World war, so I paused to reflect on his great sacrifice. The inscription etched in bronze reads: “In war and peace they plied their trade, over the angry seas, remember them as here you stand beneath these placid trees”. Another poignant reminder of the myriad seafaring associations of the city.

Bristol Bridge is the reason for Bristol being where it is. In the early days of the city, this was the best point at which to cross the river and to which to bring ships conveniently on one tide. A settlement grew around the crossing from the early 11th century. The bridge was made a permanent structure about 1247 and replaced in 1769 with the one seen today. Its roadway was widened in the 1880s. It marks the limit of navigation for any vessel that can’t pass beneath its arches.

The Old Town

As you reach the top of the St Nicholas Steps you are going into the old town – the wall was here. On our right is St Nicholas Church, first founded before 1154, with a chancel extending over the south gate of the city. The gate and old church were demolished to make way for the rebuilding of Bristol Bridge and the church was rebuilt in 1762-9 by James Bridges and Thomas Paty, who rebuilt the spire. Part of the old church and town wall survives in the 14th-century crypt. The interior was destroyed by bombing in the Bristol Blitz of 1940 and rebuilt in 1974-5 as a church museum.

As you reach the top of the St Nicholas Steps you are going into the old town – the wall was here. On our right is St Nicholas Church, first founded before 1154, with a chancel extending over the south gate of the city. The gate and old church were demolished to make way for the rebuilding of Bristol Bridge and the church was rebuilt in 1762-9 by James Bridges and Thomas Paty, who rebuilt the spire. Part of the old church and town wall survives in the 14th-century crypt. The interior was destroyed by bombing in the Bristol Blitz of 1940 and rebuilt in 1974-5 as a church museum.

The Glass Arcade runs across All Saints’ Lane and was an early example of the shopping arcade. The grand 18th-century entrance to this from High Street was designed by local builder Samuel Glascodine.

The Exchange (now St Nicholas Market) was built in 1743 by Bath architect John Wood the Elder. This became the place for trading. The clock has two-minute hands, as Bristol worked to its own time, 11 minutes behind London time, at least until the advent of the railways. The Exchange is now home to a large and varied indoor market.

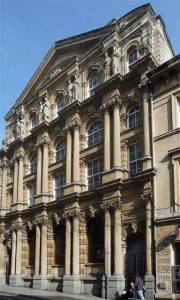

Coming out onto Corn St, opposite is The West of England Bank. Next door to the Old Council House, this large flamboyantly decorated Venetian style building by architect WB Gingell (he’s cropped up a few times), was built in 1857.

The Old Council House (now Registry Office) was built in 1827 by architect Sir Robert Smirke. It is a Greek revival style building with a fine Regency interior that includes the former Council Chamber.

The Old Council House (now Registry Office) was built in 1827 by architect Sir Robert Smirke. It is a Greek revival style building with a fine Regency interior that includes the former Council Chamber.

Corn St was the thriving hub of the old city. There was a twice weekly corn market held here from 1813 onwards. The writer Daniel Defoe, on a visit to the city, relates how the area became so thronged with ship owners, traders and merchants that they overflowed into the surrounding taverns and coffee houses. So, perhaps not surprisingly, the street has many impressive nineteenth-century buildings.

On the right at No. 43 are the Commercial Rooms (1801-11) by Charles Busby, an architect later instrumental in creating Regency Brighton. It was a merchants’ club. On the left at No. 36, the Old Bank, now the Nat West Bank, was built by Gingell in 1864-7. The paired columns are stacked two high and four wide. This building had originally been built for the Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance company and it’s fun to spot the sculpted details of firemen with axes; and in the centre, Time with an hour glass.

We loved the building at No. 37-39, the former Friends Provident Building (1931-33) by AW Roques, elevation by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. The restrained art deco style works well, as does all the metalwork – windows, balconies and the grilles on the ground floor. Note the frieze of lively dancers above the main entrance.

We loved the building at No. 37-39, the former Friends Provident Building (1931-33) by AW Roques, elevation by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. The restrained art deco style works well, as does all the metalwork – windows, balconies and the grilles on the ground floor. Note the frieze of lively dancers above the main entrance.

The Cosy Club at no. 31 is worth popping in to enjoy the marvellously ornate banking hall ceiling with dome, also a Gingell work.

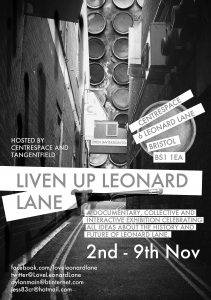

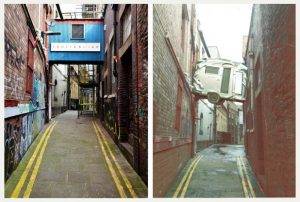

And then we head down a rather uninviting hole in the wall just a few yards aft er the Cosy Club –and it has a name, Leonard Lane, which follows the line of the old wall on the left.

er the Cosy Club –and it has a name, Leonard Lane, which follows the line of the old wall on the left.

It had been named after St Leonard’s Church, which originally stood over the Westgate, one of the original entrances to the medieval city, which became known as St Leonard’s Gate. This medieval church was one of many in the congested streets of the old city. It fell victim to the improvements being made in this area in the eighteenth century when Baldwin Street was re-routed and Clare Street created. In a Bill presented to Parliament, the church was described as “a nuisance” because it blocked the main thoroughfare. The Bill ordering demolition of the church became law in 1765. So, I suppose it’s fair to say that demolishing lovely buildings wasn’t just a 20th-century habit…

Street Art excursion

Leonard Lane has two claims to fame, take your pick:

- In tabloid-speak, it has ‘Britain’s barmiest street markings’; there are double yellow markings down it, despite the fact that at several points you can easily touch both walls. The council says they probably won’t remark the road when it’s next resurfaced – but that would be a shame really, it would lose part of its quirky character…

- It was (perhaps still is) ‘officially’ Europe’s longest environmental thoroughfare (not quite sure who checks these things out…)

Its transformation into an outdoor gallery came about through the Human Nature Project of 2015. Artist and founder of Human Nature Charlotte Webster explained how the ambitious project came about: “I lived in Bristol for a number of years, and walking down Leonard Lane I felt compelled to shift its direction. With 18 artists coming to the city on tour, one thing we know how to do is change a space. Human Nature’s focus is on our shifting relationship with the environment, so walk down Leonard Lane and you’ll see art exploring climate change, fossil fuels and extinction amongst other things all encouraging us to think about our connection to nature. It’s important to have a physical space which represents Bristol’s progressive thinking, together we can all make Leonard Lane a positive space that looks towards the future.”

Leonard Lane is also home to the Centrespace Gallery, in a former print works. It is a thriving community of artists and craftspeople offering both studio space, workshops, events and a gallery space for hire. It was founded in the late 1970s and has been running as a cooperative since 1987. It continues to develop creative opportunities for the wider community in the heart of the City of Bristol.

The Centrespace bridge links what was the old print works to the editorial offices on the other side. This was the headquarters in Bristol of the ‘Times and Mirror’, housed in a 1900 Arts and craft building with its front in St Stephen’s St. The paper was published from 1865 to 1932, one of several daily papers for Bristol.  The building is now the Bristol Backpackers’ Hostel, at the bottom of the steps.

The building is now the Bristol Backpackers’ Hostel, at the bottom of the steps.

The art gallery has a rather wonderful plan to replace this bridge with a caravan that would also serve as office and studio space.

Look left just after the bridge down some steep steps down through the town wall to St Stephen’s St, at the original quayside level. And a bit further along there’s a parish boundary marker at head height on the wall. The old town was served by eleven different parishes.

Nelson Street is renowned for the street art, and to be honest, if the art wasn’t there it would be a very dreary place and we would have cut straight up Bell Lane. But it does serve as an ominous reminder of how close the 1960s tide of destruction lapped up against the old town when a plan had been hatched to pull it all down in favour of ‘comprehensive’ redevelopment (happily quashed).

And in a happy twist of fate, it was, in fact, the street’s very dreariness that eventually made it famous the world over. In 2011, its drab grey frontings and exposed brick exteriors were transformed into a vibrant exhibition of colour as part of the ‘See No Evil’ Festival. This urban art project was the largest street art festival Europe had ever seen and saw world-class graffiti artists from all four corners of the globe coming to Bristol to display their talents. The street is now one of the best places to see cutting edge urban art in Bristol. The immense Vandal mural by Nick Walker pouring down onto the pavement below is a truly spectacular sight. There are several other notable murals, including a mother and child by artist El Mac and a Big, Bad Wolf by ARYZ.

When asked about the legacy of See No Evil, one of the artists, Dave Harvey, said: “In terms of legacy – obviously, the street itself. This street this time last year, no one came here, there was nothing on the street, it was really grey and dismal. This year Council figures show tens of thousands more people are coming down here every month to look at the art.” It’s certainly true we wouldn’t have found ourselves walking along this street if it hadn’t been for the street art!

If you go a few yards beyond our route down Broad St, you will see St John’s Conduit in the old wall. The spring feeding it rises on Brandon Hill, and the system was constructed by the Carmelite Friars as a wooden conduit in the 14th century, providing one of the first public supplies of clean water.  The water now travels under Park Street and eastwards through pipes, cisterns and tanks. During the aftermath of Second World War bombing raids, this tap was the only source of water available in the old city area. It has been moved from its original position inside the walls.

The water now travels under Park Street and eastwards through pipes, cisterns and tanks. During the aftermath of Second World War bombing raids, this tap was the only source of water available in the old city area. It has been moved from its original position inside the walls.

St John the Baptist Church is the only survivor of five wall churches. The tower and steeple stand over the main arched St John’s Gate, with small statues of Brennus and Belinus, mythical founders of Bristol. A full-size vaulted crypt is below the church, entered from Nelson Street, outside town wall.

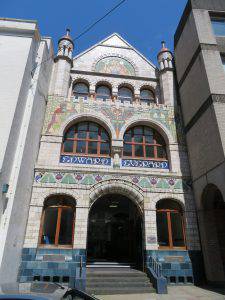

Walking down Broad St, we soon see on the left the old Edward Everard Printing Works, which for a split second we take to be another piece of street art. In fact, it was built in 1901 using ceramic tiles made by Doulton and Co. Flanking the winged Spirit of Literature figure are those of Gutenberg, the 15th-century printing pioneer, and William Morris, who designed a new lettering style for the Kelmscott Press in 1890.

Walking down Broad St, we soon see on the left the old Edward Everard Printing Works, which for a split second we take to be another piece of street art. In fact, it was built in 1901 using ceramic tiles made by Doulton and Co. Flanking the winged Spirit of Literature figure are those of Gutenberg, the 15th-century printing pioneer, and William Morris, who designed a new lettering style for the Kelmscott Press in 1890.

A little further on is the 18th century Taylors Hall with shell hood and Guild crest. The Guild of Merchant Taylors, established in 1399, controlled the trade until the 19th century. This narrow court gives a good impression of the city before the 19th-century redevelopment.

And two interesting buildings on the right; the Guildhall and Assize Courts built in 1843 by the architect RS Pope. Like many other buildings in the area, this impressive Perpendicular Gothic Revival edifice was constructed on the substantial vaulted cellars of previous buildings, in this case, the medieval Guildhall. Then, the Bank of England, built in 1846 by the architect Charles Cockerell, in Greek Revival style. Bristol was one of the first cities to have such a branch bank.

Finally, on our left, is the Grand Hotel. Built in 1865 by the architects Foster & Wood, it is another good example of the Bristol Byzantine style. It was one of Bristol’s first purpose-built hotels. The ground floor was originally fronted by shops. Christchurch, just down from the hotel, was rebuilt in the 18th century by local architect William Paty. It has a fine classical interior and a clock with colourful quarter-jack striking bells.

In case you were wondering where the ‘official’ centre of Bristol is, you’ve just reached it! But they made it difficult to spot because the statue that originally denoted it has been removed. The High Cross was located at the highest part of the Old City, erected to mark the granting of the 1373 charter that gave Bristol the status of a county. This was the historic and symbolic centre of Bristol, at the crossing of the four original main streets, Broad Street, Wine Street, High Street and Corn Street. But it was removed in 1733, a public petition claiming it to be a ‘ruinous and superstitious relick’. It was later erected at the Stourhead estate of Bristol banker Samuel Hoare.

In case you were wondering where the ‘official’ centre of Bristol is, you’ve just reached it! But they made it difficult to spot because the statue that originally denoted it has been removed. The High Cross was located at the highest part of the Old City, erected to mark the granting of the 1373 charter that gave Bristol the status of a county. This was the historic and symbolic centre of Bristol, at the crossing of the four original main streets, Broad Street, Wine Street, High Street and Corn Street. But it was removed in 1733, a public petition claiming it to be a ‘ruinous and superstitious relick’. It was later erected at the Stourhead estate of Bristol banker Samuel Hoare.

Castle Park (4.1 hectares, 10 acres) was opened in 1978 and occupies most of the site which had contained Bristol’s main shopping area. Much of this area was heavily damaged in the Blitz during the Second World War, and that which remained was subsequently demolished. The ruins of St Peter’s Church are now a memorial to the civilians and auxiliary personnel killed in the Bristol Blitz. Between November 1940 and April 1941, Bristol suffered six major bombing raids, killing 1,299 people in total. Just as with Exeter, there is much debate to this day as to how much of the old city was flattened by the Luftwaffe and how much was subsequently pulled down by a council determined to start again from scratch without the encumbrance of expensive to repair buildings.

Part-way round the park, the path crosses Castle Ditch, the remains of the moat that once surrounded Bristol Castle. It was the largest Norman castle in England, built in the 11th century by Robert the first Earl of Gloucester and illegitimate child of Henry I. Oliver Cromwell eventually demolished the castle in 1656 following an Act of Parliament. Now, only a few crumbling walls and underground chambers remain, but we certainly found a poke around worthwhile.

From here there is a good view down Temple Backs. This was once Bristol’s industrial backyard, particularly on the left bank, where in the 19th century there had been a lead works, an iron foundry, a glass bottle works, a white lead works, a railway locomotive factory, a major railway bridge, a gas works and a soap factory.

Spanning the Floating Harbour between Castle Park and Finzels Reach, Castle Bridge is the latest stage in the regeneration of Redcliffe. It is ‘de rigeur’ for urban bridges these days you have a kink in them and this one is no exception. It is the final link in a pedestrian and cycle way that links Temple Meads Station with Cabot Circus and will hugely improve access to this previously neglected part of the city.

Look over your shoulder briefly as you cross the bridge, and you will get a good view of where the River Frome joins the River Avon. UK Caving had a fun time down there in the Frome Culvert (don’t do this at home!)

Finzels Reach is a 4.7-acre (1.9 ha) mixed use development site on a former industrial site. A sugar refinery occupied part of the site from 1681, rebuilt by Conrad Finzel in 1846 to become one of the largest sugar refineries in England. Known as Finzel’s Sugar Refinery, it operated until 1881. Georges Bristol Brewery, founded in 1788, then grew to occupy most of the site by the mid-20th century, when it was the largest brewery in south-west England. Known after 1961 as the Courage Brewery, it operated until 1991. The site also includes the former Tramway Generating Station, a Grade II* listed building built in 1899 which operated as the power station for Bristol Tramways until 1941.

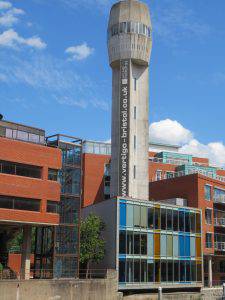

Brutalist aficionados will love the now listed 1968-built Sheldon Bush lead shot tower on the far bank just after St Philip’s Bridge, which has been converted into office accommodation and a conference room at the top. How ironic that they managed to save this one, but not the world’s first that we walked past the site of earlier; apparently that lingering sense of guilt and regret was one of the reasons for its listing, as it told a history as well as being architecturally significant in its own right.

Brutalist aficionados will love the now listed 1968-built Sheldon Bush lead shot tower on the far bank just after St Philip’s Bridge, which has been converted into office accommodation and a conference room at the top. How ironic that they managed to save this one, but not the world’s first that we walked past the site of earlier; apparently that lingering sense of guilt and regret was one of the reasons for its listing, as it told a history as well as being architecturally significant in its own right.

Valentine’s Bridge, again with its regulation curve, opened in in Feb 2000 (hence the name) but flew into a storm of controversy as to whether cyclists were or were not allowed to use it. Barriers were erected to encourage riders to dismount and walk their bikes over the bridge, but there seems to have been a change of heart after complaints were registered. A reminder of how important the cycling community is in this city – Sustrans, after all, was founded here.

Temple Quay Square has a street food market every Thursday 12-2pm, which the Guardian judged to be one of the best street food markets in Europe (a claim I haven’t been able to test since we went through on a Sunday). More than 5,000 people work in this area, so there is a big lunchtime demand for something different and original.

Temple Quay Square has a street food market every Thursday 12-2pm, which the Guardian judged to be one of the best street food markets in Europe (a claim I haven’t been able to test since we went through on a Sunday). More than 5,000 people work in this area, so there is a big lunchtime demand for something different and original.

And so, our walk finishes as we head through the ‘back door’ of Temple Meads Station, an odd way to arrive in some respects. The station is undergoing a major transformation, you can find out more at http://www.robertsewell.com/templemeads. I often say this, but this time I really mean it – I hope you will agree, the best walk ever!!

THE ROUTE

- Set out down the Station Approach and take a left at bottom into Temple Gate and left again into Cattle Market Rd; proceed under the railway viaduct

- On the far side, follow the river path along the north bank of the river that starts just after the new Brock’s Bridge, following it for 1.4 km until you reach the Spark Evans Park

- At Sparke Evans Park, cross over the river on the footbridge past a new development and then into Edward Rd

- On reaching the main Bath Rd, turn right and then cross over at the pedestrian crossing; a few steps on, take the imposing entrance into the Arnos Vale Cemetery (not the first cemetery entrance)

- Once in the cemetery loop around to the left, and the path swings round and eventually brings you to the Atrium Café and facilities; cut up to the right of this, up the hill and make your way by any of the several routes to the southwest Cemetery Rd exit

- Proceed along Cemetery Rd, cross the main Wells Rd, turn left and take the first right into Crowndale Rd and you will soon reach the south-east corner of the Perrett’s Park

- Walk SW along the top of the park, until you see a metalled path leading directly down to an exit on the west of the park into Ravenhill Rd, which you take

- Head to the N end of Ravenhill Rd, turn left into St John’s Lane, over the pedestrian crossing, continue down St John’s Lane then take the second right up Marmaduke St to reach Victoria Park

- Take the path at right angles to the entrance, which takes you eventually to the top-right corner of the tennis courts; at this point take the path heading right (NE) to the exit of the park in St Luke’s Rd close to the railway bridge

- Walk under the railway bridge to the end of the road where it meets York Rd

- Cross at the traffic lights and head across the pedestrian footbridge, called the Banana Bridge, across the River Avon

- Cross Clarence Rd and follow the path running north west through the housing estate, into Somerset Square, through the gardens in the centre of the square, crossing Prewett St up Ship Lane until you reach Colston Parade and St Mary’s Redcliffe Church

- Head through the churchyard to the west end, then exit onto Redcliffe Hill, which you cross. Go up the hill a few yards and turn right into Redcliffe Parade, which you walk along almost to the end where you take steps leading down to the quayside

- Follow the quayside path S to cross Bathurst Basin Footbridge, then keep to the quayside along Merchant’s Quay to reach the Prince St swing bridge

- Turn left immediately after the bridge, following the quayside round to Pero’s Bridge, where you turn sharp right into Farr’s Lane, crossing the busy Prince St to enter Queen Square at the SW corner

- Walk to the statue in the centre, then due N, exiting into King William Avenue, then right into King St

- Take the first R into Queen Charlotte St, then the first L into Little King St, to reach Welsh Back which you follow N all the way to Baldwin St

- When you reach Baldwin St, cross over and climb up St Nicholas’ Steps, up through All Saints’ Lane, with the market on both sides of you

- Turn left when you reach Corn St, head SW and turn right up a passage called Leonard Lane just after the Cosy Club

- Follow Leonard Lane to its end, turn left in Small St and then right into Quay St

- Take the first right through the arch into Broad St and proceed down to the end where it meets Wine St, where you turn left

- Cross into Castle Park when you are level with the derelict St Peter’s, which you walk past the west end of; then head E towards the castle remains. Take a look around and then cut back W down to the Castle Park Landing

- Then cross the Castle Bridge footbridge across the water, after which head S down Hawkins Lane, across Temple Cross and then down Old Terrace St

- Turn left at Counterslip, and then cut down to the right just before the St Philip’s Bridge and follow the water course south, below the Temple Way, until you reach the Valentine Bridge

- At this point the path swings round to the right, skirts the east side of Temple Quay Market and heads into the side entrance to Bristol Temple Meads Station; and the walk is completed!!

PIT STOPS

Kate’s Kitchen at Arnos Vale Café (0117 971 4850, www.facebook.com/kateskitchenarnosvale) is a must, not least to support the superb efforts of the volunteers to keep this Arcadian wonder open.

Mrs Brown’s Café, Victoria Park, next to the park keeper’s lodge, close to Somerset Terrace; open spring to December.

Small Street Espresso, 23 Small Street, Bristol BS1 1DW (Old Town, www.smallstreetespresso.co.uk (closed Sundays)

Edna’s Kitchen, Castle Park, specialises in healthy Middle Eastern and Mediterranean food with lots of vegetarian options.

Edna’s Kitchen, Castle Park, specialises in healthy Middle Eastern and Mediterranean food with lots of vegetarian options.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

St Nicholas Market (BS1 1JQ) voted one of the best indoor markets in the UK

PLACES TO VISIT & THINGS TO DO

St Mary Redcliffe Church www.stmaryredcliffe.co.uk

Redcliffe Caves are man-made caves in the Redcliffe area of Bristol, close to St Mary Redcliffe church. Much of their history is vague but French and Spanish prisoners were held there in the 18th century. Note that the caves are only open on certain event days such as the Bristol Doors Open Day in September. http://www.redcliffecaves.org.uk/

M Shed, Wapping Road, Bristol BS1 4RN (0117 352 6600) just a stone’s throw from the Prince St Bridge on the south side if you’re feeling like some culture along the way.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Follow: Harbour Heritage Trails

Take: This Walled City Walk follows the town walls of Norman Bristol. http://bristololdcity.co.uk/old-city-heritage-trail. Beautifully constructed.

Explore: The Frome Valley Walkway, a public footpath, 18 miles (29 km) long, that runs almost the entire length of the river from Old Sodbury to Bristol. A guide pamphlet has been published.

Leave a Reply