Britain’s version of Rio?! – bright colours, vibrant street life, informal lifestyles, although admittedly a bit wetter

This walk takes you through the Georgian delights of Clifton, over the iconic Clifton Suspension Bridge, through the delightful Ashton Park estate, then back along the bustling Floating Harbour.

WALK DATA

Distance: 10.3 km (6.4 miles)

Height Change: 102 metres

Typical time: 2 ½ hours

Start & Finish: College Green (BS1 5UY)

Terrain: Mix of pavement and countryside; sturdy footwear recommended

BEST FOR…

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | College Green, Brandon Hill, Birdcage Walk, Victoria Square, The Mall Gardens, Clifton Down, Ashton Court Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Avon, Floating Harbour |

| Stunning cityscape | Top of the Cabot Tower; The Clifton Suspension Bridge |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | Bristol Cathedral (from the 12th C), Ashton Court (from the 11th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Most of Clifton; especially notable is Royal York Crescent |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Bristol Central Library (1906), Cabot Tower (1897), Wills Memorial Building (1925), The Victoria Rooms (1842), Clifton Suspension Bridge (1864) |

| Industrial Heritage | SS Great Britain, Floating Harbour cranes, tugs and steam railway |

| Modern (post-1918) | City Hall (1956), Pero’s Bridge (1999) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Boston Tea Party, Park St; Primrose Café, Boyce’s Avenue; Arch House Deli, Boyce’s Avenue; Olive Shed, Floating Harbour |

| Quirky Shopping | Clifton Arcade |

| Places to visit | Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, Royal West of England Academy of Art, M Shed |

| Popular annual festivals & events | The Green Squares and Secret Gardens of Clifton – www.cliftonhotwells.org.uk (early June); Bristol Harbour Festival (July); Bristol International Balloon Fiesta (August) |

City population: 449,300 (2017 est.)

Urban population: 617,000 (2011 census)

Ranking: 10th largest city in the UK (Wiki)

Date of origin: 11th century

‘Type’ of city: Maritime

City status: granted in 1542, when the Diocese of Bristol was founded

Some famous inhabitants: Robert Southey (poet), Banksy (artist), Cary Grant (actor), Billy Butlin (holidays), Sir Humphrey Davey (inventor), John McAdam (roads), John Wesley (preacher), John Cabot (explorer), Massive Attack (music), Jeremy Irons (actor), John Cleese (comic), David Walliams (comic), JK Rowling (writer), Damien Hirst (artist), Tony Benn (politician)

Notable city architects/planners: During the Georgian period, the main architects and builders working in Bristol were James Bridges (1725-1763) – The Royal Fort, John Wallis, and Thomas Paty (1713-1789) with his sons John and William Paty. They put up hundreds of new buildings. Sir George Herbert Oatley (1863-1950) was notable in the 20th century for several buildings, including the Wills Memorial Building. The first elected mayor of Bristol (from 2012-16), George Ferguson, was an architect, former RIBA president and a founding director of The Academy of Urbanism.

Number of listed buildings (the whole of Bristol): 4,600 listed, of which 100 are Grade I and 212 Grade II*

Films shot here: A Day in the Death of Joe Egg (1972), The Medusa Touch (1978), Truly, Madly, Deeply (1990 – Birdcage Walk), Starter for Ten (2006 – Royal York Crescent). There is a very useful set of movie maps at; http://www.filmbristol.co.uk/bristol-movie-maps

TV series shot here: Skins (Brandon Hill), Sherlock (several locations, see http://www.filmbristol.co.uk/content/files/Final%20sherlock.pdf), Doctor Who, Casualty

Estimated % of green space in the city (Eski): 29% (3rd out of Top 10 cities)

CONTEXT

Bristol feels somehow different from other British cities; it’s definitely not a traditional cathedral-style southern city, but nor could it be described as a northern city. It’s very much a city of its own making; and there lies its appeal for many, making it high up people’s wish list of places they’d like to move to.

Of course, it has always had the advantage of a stunning natural setting. The Avon Gorge is a thing of wonder that feels like nature intruding upon man’s urban landscape and winning hands down. And the many hills and slopes of the town create great vistas of terraces and parks.

But it is the people of Bristol who have really given character to the place; they have a strong sense of individuality and creative expression. It’s the only city I’ve come across where the residents like to wave at the Googe StreetView van as it passes, so as I do my street research I am left with a timeless sense of it being a friendly place. The city has something of the feel of Rio de Janeiro about it – the hills, the vibrancy of the inhabitants and above all the painted houses stretching up every slope! It’s hard to find a part of Bristol that isn’t bursting with colour and creativity, and that’s why the city has been named as one of the 10 most colourful in the world by Buzzfeed.

On trying to find out why so many of Bristol’s houses have been painted in bright colours, the only answer I could come up with is ‘because Bristolians like it’. There is a freedom of expression here which creates a city that is exhilarating, beautiful and frequently haphazard and untidy at the same time – it feels like a frontier city, but it’s been around since the 10th century!

Bristol’s history as a trading and seafaring port meant it has always been open to influences from around the world and been a place of innovation. In the 19th century, the city was closely associated with the genius of Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who designed the Great Western Railway between Bristol and London Paddington, two pioneering Bristol-built ocean going steamships (SS Great Britain and SS Great Western) and of course the Clifton Suspension Bridge.

Bristol has also often led the national debate on environmental issues. In 2015, it was named as European Green Capital of the Year. Almost a third of Bristolians either walk or cycle to work, by far the highest levels within the Top 10 UK cities. Back in the 1970s, Sustrans was founded in the city by a group of cyclists and environmentalists, motivated by emerging doubts about the desirability of over-dependence on the private car. Starting with the Bristol & Bath Railway Path, they went on to create the national cycle network that has helped re-define the nation’s attitudes to cycling.

It’s a stunning city, but also full of blemishes. Much of the centre was destroyed by Luftwaffe bombs in the Second World War, destroying or damaging 100,000 buildings. But a second disfigurement took place in the city with the mindless re-building of the 1960s and 70s which led to a disastrous road system and faceless high-rise buildings. Arriving in Bristol along the M32 is still a dispiriting experience – it takes a while to get the measure of the place, nothing like a Bath or a Brighton that you can instantly fall in love with.

These post-war planning blunders are only now being rectified bit by bit, but at least the city you see today is dramatically more pleasant to walk around than it would have been only twenty years ago – with Queen Square, College Green and Portland Square all restored, and the dockyards preserved and converted to leisure rather than bulldozed over. And of course, Clifton remains the jewel in the crown it has alway been.

THE WALK

Our walk starts on College Green which, if you were pushed to say where the ‘official’ centre of Bristol is, this would probably be it. It has been a green space since the 12th century, much altered over the years but still retaining its rough shape and much improved in the early 1990s when the southern side road was closed to traffic, thus linking the cathedral directly back to the green.

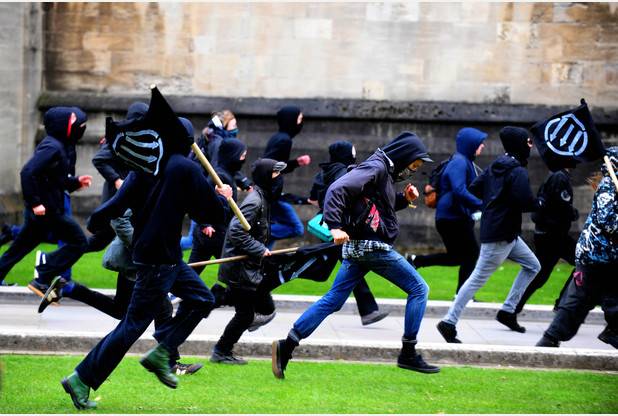

Much of the life of Bristol life has passed through here – the day we were there a cycle road race, and frequently it has been a place of demonstration. In 1831, it was the scene of riots in support of the Reform Bill that led to the razing of the Bishop’s Palace. In 2011, it became the site for Occupy Bristol, a camp established as part of the worldwide “Occupy” protests against social and economic inequality; and hardly a week goes by on the green without a demonstration of one sort or another.

Another day, another demo in College Green

Much of Bristol has an informal, laissez-faire, unplanned feeling to its architecture, but not so College Green, which would undoubtedly form the city’s submission (perhaps it’s only one) for ‘classic city civil space’. On the south side is Bristol Cathedral, dating back to the 12th century; along the west side is City Hall, a handsome 1950s brick building with a water feature in front; and in the south-west corner the handsome Bristol Central Library, an Edwardian Grade I listed building, with some beautiful friezes above the windows, my favourite Bristol building.

Having admired the Bristol Central Library from all sides (it’s worth going round the back, where it is five storeys rather than the three on the front due to the slope, and it looks much more art deco-like), we strolled along Deanery Rd in search of our first Banksy. Peering down into Lower lamb St we spotted it:

“You don’t need planning permission to build castles in the sky ….” OK, we were not overwhelmed, but nonetheless, we still felt pleased that we had found it. To make Banksy-hunting that bit easier, you can find all the locations at the extremely helpful website http://banksytours.co.uk/

Brandon Hill (8.2 hectares, 20.3 acres) is a beautiful pocket-sized park with bags of character and history. It was granted to the council in 1174 by the Earl of Gloucester, and used for grazing until 1625 when it became a public open space, possibly the oldest municipal open space in the country. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, it was a popular venue for public meetings by reform groups like the Chartists. Most famously in 1832, it was the site of the Great Reform Dinner attended by 5,500 local dignitaries and gate crashed by a crowd of 33,000 uninvited protesters (how did they all fit in?!) who overturned tables amidst ‘riotous scenes’. Today there are several groups gently picnicking but no sign of an imminent insurrection.

From 1840 onwards Brandon Hill was improved with walls and walks. A more peaceful crowd of 30,000 watched the launch of SS Great Britain from the hill in 1843. It remained a site of popular protest, however, with 20,000 unemployed workers gathering at the top the hill in January 1880 to protest their plight. It was opened as a nature reserve by Sir David Attenborough in 1980; a pioneering example of urban conservation, with a small nature reserve and open grassland.

At the summit is the Cabot Tower, opened in 1897 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of John Cabot’s voyage from Bristol to Newfoundland in 1497. Climb up to the top and you will be rewarded by an amazing view in all directions!

Trip Advisor reviews of the park are uniformly positive: “This place is wonderful. The hilly environment means there is always a surprise around every corner. The views are outstanding and the children love the play park. Cabot Tower is an architectural gem and the views from the top across the park and harbour must be the best in the City.” We agree, definitely not to be missed. There is an excellent downloadable leaflet of the park available at http://www.bristolparksforum.org.uk/brandonhill/TreeTrail.pdf – in particular, it points you to several of the most unusual of the park’s nearly 100 different species of trees.

Having climbed the hill, we dropped down again to Berkeley Square, and ventured into its slightly neglected but nonetheless charming green space in the middle; this faded charm and slight untidiness, whether by design or lack of funds, is a feature of many Bristol parks, which I suspect delights some and disappoints others, but is very much part of the Bristol character.

Anyway, at least it hasn’t been tarmacked over, which it just might have been if you consider that the eponymous John McAdam lived at No 23 in the early nineteenth century; and this is where, whilst he was surveyor of the Bristol Turnpike Trust he invented the process called ‘macademisation’ that became famous the world over and turned out to be the greatest advance in road construction since Roman times.

The remains of Bristol’s replica High Cross is to be found in the gardens too. The original was removed as a traffic obstruction in the eighteenth century and sold as a garden ornament.

If you’re an obscure street name collector, pop out of the north east of the square to bag ‘There and Back Again Lane’ – sadly, other than the name, a dispiriting street full of rubbish bins.

Coming out onto Triangle South, we got a fabulous view of the Wills Memorial Building, built in 1925 and the last great Gothic secular building to be built in this country. It was paid for by George and Henry Wills of the tobacco family, in memory of their father, who had enabled the foundation of Bristol University in 1909 with a gift of £100,000. The brothers wished to create ‘an architectural elevation at once worthy of the University and an ornament to our native city’ – and this they certainly achieved; it is now very much a symbol of the city.

Pro-Cathedral Lane is the ‘secret passage’ which propelled us up to the magical Georgian world of Clifton. Although Clifton has no formal boundaries, the name is generally applied to the high ground stretching from Whiteladies Road in the east to the rim of the Avon Gorge in the west, and from Clifton Down and Durdham Down in the north to Cornwallis Crescent in the south.

It is one of the oldest and most affluent areas of the city, much of it having been built with profits from tobacco and the slave trade. Mentioned in the Domesday Book, it was originally a separate settlement but became attached to Bristol by continuous development during the Georgian era and was formally incorporated into the city in the 1830s. Grand houses that required many servants were built in the area. Although some were detached or semi-detached properties, the bulk were built as terraces, many with three or more floors. Our walk took us past many of these houses; and it is their sheer scale and extent that amazes, street after street of Georgian elegance and symmetry.

Swinging round to Clifton Hill, we then cut right up the atmospheric Birdcage Walk. Taking its name from the green arches that line the walkway across the graveyard, this is all that remains of St. Andrew’s Church – built in the 12th century, but destroyed in the Bristol Blitz. We were struck by how tranquil and relaxing even a small handkerchief of green space like this one can be.

Victoria Square was built around 1840, and its central gardens were originally private but are now a much valued central public park. I’m guessing the metal railings were removed to support the war effort in the Second World War and were never replaced. There are many mature specimen trees and it is a delightful space much loved by local people.

It was called Victoria Square because high in the centre of the terrace on the north side is the royal coat of arms. The terrace was apparently built to resemble a palace and it was hoped that Queen Victoria would come and stay there. She never did.

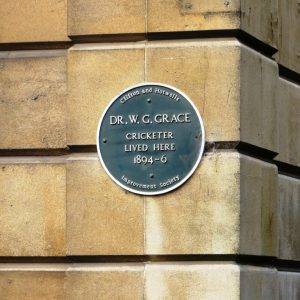

But another famous Victorian that did was WG Grace, who presumably at some stage threw a cricket ball in the gardens, much as a family are doing today. The house where he lived is just to the left of Rodney Place, and you can see the blue plaque to commemorate his residence.

Rodney Place was named after Admiral Rodney, who was especially popular in the city because he secured British control of Jamaica, where many Bristolians had investments. It’s a delightful passage and you will find it very hard not to pause for a coffee or to pick something up from the deli or greengrocer.

If you think you’re Clifton-ed out by now, hang on as we’re about to get to the VERY best bit, Royal York Crescent and Sion Hill. Royal York Crescent is the finest street in Clifton, with its elegant terraced houses, raised pavement and expansive views south over the harbour. Walking along it, we felt instantly like characters in a Jane Austen novel, lacking only parasols and witty rejoinders. And in its time it’s had some pretty swanky residents too, including the wife of Napoleon III who went to school there.

Stick with us on the winding route we take next, although it doesn’t seem that logical, but I really want to take you through the Mall Gardens, a long thin strip of public communal gardens that have a very special feel about them, created in around 1840 when the surrounding terraces were constructed, and now maintained by the council supported by a residents’ garden committee, the MGRA (Mall Gardens Residents’ Association), who also organise social events to raise funds for work in the garden and for local charities. It is these Associations that are often the lifeline for the well-being of green spaces in cities, and we should be eternally grateful to them.

Coming back out onto Sion Hill was another ‘wow’ moment as we saw the Clifton Suspension Bridge ahead of us (it was my first time ever!), and walked past the Avon Gorge Hotel and The Rocks Railway, a funicular railway constructed in 1893, closed since the 1930s and now in the process of restoration.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is Bristol’s best-known landmark and provides unbeatable views along the gorge. The idea of building a bridge across the Avon Gorge was first muted in 1753. Original plans were for a stone bridge and later iterations were for a wrought iron structure. In 1831, an attempt to build Brunel’s design was halted by the Bristol riots, and the revised version of his designs was built after his death and completed in 1864. It’s still an active bridge used by cars and pedestrians, but weight restrictions apply. I notice that during the Balloon Fiesta, for example, it has to be closed to avoid having too many feet trampling on it at once, which presents weight problems but also swaying/resonance problems (remember what happened to the Millennium Bridge in London when it first opened).

In admiring the spectacular view from here, one perhaps forgets how amazing the nature of the Avon Gorge itself is too. David Goode, in his book ‘Nature in Towns and Cities’ writes: “Relatively few cities in the UK have rocky hills or cliffs within the urban sprawl, but where they do these places can be some of the richest botanical sites despite being part of a city. The Avon Gorge is just such a place, one of the ‘hot spots’ for botanical diversity in the UK. It has a remarkable number of rare plants, including 27 that are nationally rare or scarce. Some are endemic species. Bristol whitebeam and Wilmott’s whitebeam occur nowhere else in the world, and Bristol rock cress and rounded headed leek nowhere else in Britain.” The gorge is protected as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

Once across the bridge and having ogled the view long enough, we ascended Bridge Rd where on the right there are vast Victorian detached houses which no doubt were built once the bridge was open and belonged to wealthy Bristol merchants who were now only a short carriage ride away from their businesses.

And then suddenly, the houses come to an abrupt halt, as we enter the rural and tranquil Ashton Court Estate, almost entirely surrounded by Somerset countryside. Owned by Bristol Council since the 1950s, the estate is now a major recreational area, comprising about 344 hectares (850 acres) of woodland and meadows, laid out by Humphry Repton, the great landscape designer; and Ashton Court Mansion, which dates from the 12th century and has additions from almost every era.

We thoroughly enjoyed the descent through the woods of the Summerhouse Plantation, a respite from the heat of the day, and we felt as if we were in deep country. And soon we were back down in the valley, walking around the boundary of a cricket pitch where youngsters and their earnest parents were locked in combat with a team from ‘another place’; all in view of the Clifton Suspension Bridge…

…and then through the Kennel Lodge allotments, where we observed a mix of old men in flat caps certain in every movement; and young men with lots of facial hair and earnest looks, wondering if what they were planting would ever really grow into a real anything. The allotments are run by the ‘Hotwells and District Allotment Association’ and they set quite exacting standards for new tenants: “From the start date of your tenancy agreement, you have a three month period in which formal notice for non-cultivation cannot be issued. After that time you will receive a Notice to Remedy if at least 75% of your plot is not at a good level of cultivation.” Better get a move on then! But no doubt that is why these allotments generally look in such good shape.

The Ashton Avenue Bridge is now a MetroBus with a footpath running alongside it. MetroBus is part of a package of transport infrastructure improvements which have been designed to help unlock economic growth, tackle poor public transport links in South Bristol, long bus journey times and high car use. MetroBus vehicles have priority over other traffic at junctions and use a combination of segregated busways and bus lanes, reducing journey times by up to 75 per cent. In my mind this is a great initiative to get people out of cars and on to public transport and walking.

Bristol Harbour covers an area of 70 acres (28.3 ha) and has existed since the 13th century but was developed into its current form in the early 19th century by installing lock gates on a tidal stretch of the River Avon in the centre of the city and providing a tidal by-pass for the river. It is often called the Floating Harbour as the water level remains constant and it is not affected by the state of the tide on the river.

The harbour is nowadays a tourist attraction with museums, galleries, exhibitions, bars and nightclubs. As we walked east along the harbour we saw our second Banksy, ‘ just on the right just after the Baltic Wharf Marina, before Sydney Row.

SS Great Britain is a museum ship and former passenger steamship, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel for the Great Western Steamship Company’s transatlantic service between Bristol and New York. While other ships had been built of iron or equipped with a screw propeller, Great Britain was the first to combine these features in a large ocean-going ship. She was the first iron steamer to cross the Atlantic, which she did in 1845, in 14 days.

The M Shed is located on Prince’s Wharf beside the Floating Harbour in a dockside transit shed. Its name is derived from the way that the port identified each of its sheds. M Shed is home to displays of 3,000 Bristol artefacts and stories, showing Bristol’s role in the slave trade and items on transport, people, and the arts. It also displays Banksy’s ‘Grim Reaper’.

Normally moored in front of the museum is a collection of historic vessels, which include a 1934 fireboat and the Mayflower, the world’s oldest surviving steam tug.

Finally, we crossed over the harbour at Prince St and then took a left over Pero’s Bridge (opened 1999), a pedestrian footbridge named in honour of Pero Jones, who came to live in Bristol as the slave of John Pinney. Composed of three spans, the outer two are fixed and the central section can be raised to allow tall boats to pass along the floating harbour. The most distinctive features of the bridge are the pair of horn-shaped sculptures which act as counterweights for the lifting section.

Millennium Square, like most of these types of ‘lifestyle’ squares, has a de rigueur large silver ball in it; and perhaps more interesting are the five produce beds, themed so that each bed tells a story of how a small, urban space can be used to grow the maximum amount of crops. Another reminder that Bristol likes to think differently and creatively.

Oh, and there’s quite a nice Cary Grant statue. On which note we head North by Northwest across the main Anchor Rd, cut up the steps to the immediate east of the cathedral and we are back once again in College Green. Got a better picture of Bristol now?!

THE ROUTE

- Start at the Cathedral and walk along the south side of College Green, turning right into College St, then turning left up Brandon Steep and thence into Brandon Hill Nature Park

- Walk up the park, skirting round the right-hand side of the Cabot Tower to the exit into Berkeley Square

- Exit on the other side into Triangle South, then turn left into Queen’s Rd up the hill until you reach the junction

- Opposite you will see Pro-Cathedral Lane, which you take to Park Place; then left into Meridian Place, then York Place and Clifton Hill

- Turn right here up the delightful St Andrew’s Church (Birdcage) Walk; at the far end turn left and cross the road into Victoria Square

- Walk W through Victoria Square through the charming Boyce’s Avenue. Cross the Clifton Down Rd, then head south until you reach Royal York Crescent, at which point you turn right, walking the length of the raised pavement

- At the end turn right into Sion Hill, then next right into Princess Victoria St; walk to the east end, then enter the narrow and exquisite Mall Gardens, doubling back on yourself to Sion Hill once again

- You emerge on Sion Hill with a fabulous view of the Clifton Suspension Bridge, which you cross. Proceed up the hill to the top of Bridge Rd (do NOT take the left turn down Burwalls Rd) and enter into Ashton Park

- Skirt left at the end of the first plantation and follow the edge of the deer park to the Summerhouse Plantation. Pass down through the woods and emerge the other side to join a track, with the University of the West of England on your right

- At this point you are joining the Festival Way; turn left at the end of Kennel Lodge Rd, then immediately right along a path which takes you back to the town centre via Ashton Avenue Bridge

- On reaching the Cumberland Road, cross over and join the Harbourside Walk, also well marked. Follow this all the way to the Wapping Rd Bridge, which you cross

- Follow the path left along the harbour, then cross Pero’s Footbridge; follow the path on the other side, which swings right to Anchor Rd, which you cross at the pedestrian crossing, going up some steps on the other side to a path that leads back to College Green.

PIT STOPS

Boston Tea Party, 75 Park St, BS1 5PF (0117 929 8601) Favoured by students for its brilliant breakfast, smoothies and proximity to the university.

Primrose Café, 1, The Clifton Arcade, Boyce’s Ave, BS8 4AA (0117 946 6577, www.primrosecafe.co.uk) The sort of café it’s very hard to pass by without going in.

Arch House Deli, Boyce’s Ave, BS8 4AA (0117 974 1166, www.archhousedeli.com) Sit in the café or put together a mini-picnic to eat on Clifton Down.

Olive Shed, Floating Harbour, Princes Wharf, BS1 4RN (0117 929 1960, www.theoliveshed.com) If you’re feeling a bit peckish by now, this is a great place for tapas and harbour-watching; also just does drinks.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Clifton Arcade and Boyce’s Avenue. Originally opened in 1878, it later fell into disuse but has recently been restored and now houses a community of small shops. An interesting assortment, from jewellery, vintage furniture, pre-loved clothes, a hairdressers and The Boutique Bakehouse.

PLACES TO VISIT & THINGS TO DO

Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, Queens Rd, BS8 1RL (0117 922 3571, www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-museum-and-art-gallery ) Archaeology, geology and art.

Leigh Woods National Nature Reserve is a fine tract of ancient woodland on Bristol’s doorstep in the Avon Gorge. Just to the north after Clifton Suspension Bridge.

M Shed, Princes Wharf, Wapping Rd, BS1 4RN (0117 352 6600, www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/m-shed) Explore the city through history: its places, its people and their stories.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Read: Pevsner Architectural Guides – Bristol – by Andrew Foyle

Read: ‘Nature in Towns and Cities’ by David Goode

Leave a Reply