Bridges, steep inclines, action!

Newcastle grabs you by the throat and never lets you go, with all the ingredients of a great urban ramble – epic location, great buildings, loads of attitude.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 7 km (4.4 miles)

- Typical time: 1 ¾ hours

- Height change: 66 metres

- Start & Finish: Newcastle Central Station (NE1 5DL)

- Terrain: 100 ft steep ascent from the quayside; all on pavements

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Leazes Park, Sir Bobby Robson Memorial Garden, Charlotte Square, Waterloo Square, Times Square |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Tyne, Lort Burn, Leazes Park Lake |

| Stunning cityscape | Top of Castle Keep, The High Level Bridge, Sage Gateshead, The Baltic Centre for Contemporary Arts, top of Grey’s monument (limited opening – book ahead) |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | Cathedral Church of St. Nicholas (15th C), Castle Keep (11th C), The Guildhall (1650s), Bessie Surtees House (16th C), Morden Tower (1290), Blackfriars Monastery (13th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Literary and Philosophical Society (1825), Moot Hall (1811), Church of St Ann (1767), All Saints’ Church (1786), Grainger Town (1824-1841), Leazes Terrace (1830) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Newcastle Central Station (1850), Old Post Office (1870s), The Central (1856), Central Arcade (1906), Market Keeper’s House (1840), Church of St Mary’s (1842) |

| Industrial Heritage | Turnbull’s Warehouse (1890s), High Level Bridge (1849), Tyne Bridge (1928), Swing Bridge (1876), Victoria Tunnel (1839) |

| Modern (post-1918) | Sage Gateshead (2004), The Baltic Centre for Contemporary Arts (1950s & 2002), Millennium Bridge (2002), Law Courts (1990), Newcastle City Library (2009), Civic Centre (1967), International Centre for Life (2000) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Baltic Kitchen, Long Play Café, Quay Ingredient, Quilliam Brothers, Les Petits Choux |

| Quirky Shopping | Central Arcade, Grainger Market |

| Places to visit | Castle Keep, The Baltic Centre for Contemporary Arts, Laing Art Gallery, Great North Museum, Victoria Tunnel, Discovery Museum, Life Science Centre |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Exhibition of the North (summer 2018), Hoppings Funfair on Town Moor (June), Chinatown (Stowell St – Chinese New Year), Newcastle Community Green Festival (Leazes Park – June), Exhibition Park Mela (Aug) |

City population: 268, 064 (2011 census)

Urban population: 879,996 (2011 census)

Ranking: 18th largest city in the UK

Date of origin: 2nd century

‘Type’ of city: Maritime trading cit

City status: granted 1882

Some famous inhabitants: Ant & Dec (entertainers), Peter Higgs (theoretical physicist, Higgs’ boson), Sting (musician), Catherine Cookson (author), Paul Gascoigne (footballer), John Wesley (founder of Methodism), Ludwig Wittgenstein (philosopher), Alan Shearer (footballer), Rowan Atkinson (comedian), Peter Beardsley (footballer), Neil Tennant (Pet Shop Boys), Dr Miriam Stoppard (agony aunt), Brian Johnson (AC/DC), Cheryl Cole (Girls Aloud), Lindisfarne (pop group).

Notable city architects/planners: John Dobson (1787 – 1865), Richard Grainger (1797-1861), Thomas Oliver (1791-1857) T. Dan Smith (1915-1993), Terry Farrell (1938-)

Number of listed buildings: 810, of which 53 are Grade I and156 Grade II*.

Films shot here: T. Dan Smith: A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Utopia (1987), Get Carter (1971) – see a brilliant 11-minute review of the locations at Get Carter: Revisited on YouTube, Clouded Yellow (1951), Payroll (1961), Stormy Monday (1988), Purely Belter (2000), Goal! (2003), Hum Tum Aur Ghost (2010).

TV series shot here: 55 Degrees North, Auf Wiedersehen, Pet; Geordie Shore Hebburn, The Likely Lads, Our Friends in the North, When the Boat Comes In, Wire in the Blood.

Famous quotes about the city:

“People are very proud of Newcastle, very proud to come from here. This is a working class City and they just want to enjoy themselves and live life to the full. They work all week, pick their wages up at the end of the week and they spend it over a weekend by having a good time and watching the football. That’s our life.” Alan Shearer

“I think every English actor is nervous of a Newcastle accent.” Alan Rickman

“The best sun we have is made of Newcastle coal, and I am determined never to reckon upon any other.” Horace Walpole

CONTEXT

First and foremost, Newcastle has a dramatic geographical setting; arriving by train is perhaps the most exhilarating arrival in any British city, perched atop the 100 ft deep Tyne Gorge waiting for a station platform, and hoping one doesn’t free up too quickly before one has had a chance to gorge on the views in both directions and the city glistening on the north side.

The city developed around the Roman settlement Pons Aelius and was named after the ‘new castle’ built in 1080 by Robert Curthose, William the Conqueror’s eldest son. The city grew as an important centre for the wool trade in the 14th century and later became a major coal mining area. The port developed in the 16th century and, along with the shipyards lower down the River Tyne, became one of the world’s largest shipbuilding and ship-repairing centres.

In the 19th century, the city was a powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. Local innovations included the development of safety lamps, Stephenson’s Rocket, Lord Armstrong’s artillery, Joseph Swan’s electric light bulbs and Charles Parsons’ invention of the steam turbine, which led to the revolution of marine propulsion and the production of cheap electricity.

In terms of its townscape, Newcastle has had four stages of architectural development all of which remain very visible to this day, creating a huge variety of styles and impacts that add further to the visual appeal of the city:

- Medieval, quayside-based

In several parts, Newcastle retains a medieval street layout. Stairs from the riverside to higher parts of the city centre and the Castle Keep, originally recorded in the 14th century, remain intact in several places. Many buildings in Close, Sandhill and Quayside date back to the 15th century. Ian Nairn describes it eloquently:

“It is built on one side of a hundred-foot gorge, and the medieval town struggled up it from the quayside, producing dozens of sets of steps or ‘chares’ which even in their present neglect can produce a kind of topographical ecstasy as you go up and down, perpetually seeing the same objects in a different way.”

- The age of planning – Grainger

As the city became wealthier, so it needed to expand and the obvious place was the plateau behind the castle. This is where Richard Grainger stepped in in the 1820s with a plan for a new town that ingeniously and almost imperceptibly linked with the old arteries of the town (contrast that with new towns today). His (main, but not only) architect was John Dobson.

This became the famous Grainger town, a series of streets almost entirely in the ‘Tyneside Classical’ style and largely intact to this day. Nikolaus Pevsner describes Grey Street as one of the finest streets in England. The street curves down from Grey’s Monument towards the valley of the River Tyne and was voted England’s finest street in 2005 in a survey of BBC Radio 4 listeners. Of Grainger Town’s 450 buildings, 244 are listed, of which 29 are grade I and 49 are grade II*.

- The age of modernism – T. Dan Smith

The redevelopment of the city in the 1960s was spearheaded by the infamous T Dan Smith, City Mayor, who envisaged the city as a ‘Brasilia of the North’, or as a new Milan or even Manhattan. He motored around the city in his Jaguar (licence plate: DAN 68) and ran the place in the manner of an American-style city boss. Key decisions were taken unilaterally, and urban change – to create ‘a city free and beautiful’ – was rammed home.

But Smith, who also headed the regional development corporation, became embroiled in a corruption scandal that involved Poulson and was jailed for six years in 1974. In his subsequent autobiography, he still mused of a Newcastle in the image of Athens, Florence and Rome, and said he “wanted to see the creation of a 20th-century equivalent of Dobson’s masterpiece. We’ve got to talk in terms of new cities. Just as in the Industrial Revolution, we [Newcastle] were ahead of our time, and in the age of leisure we ourselves will also be leading the way.”

The legacy of that architectural period is still very apparent, although I must confess we avoid much of it on our walk: inner-city trunk roads, the metro, overhead walkways, the central Eldon shopping precinct hard up against Georgian elegance, the Cruddas Park and Byker Wall council housing, the Swan House development; part of the new brutalism that was then sweeping through architecture and the arts. But T. Dan Smith was also responsible for the Civic Centre, which we marvel at, so his vision wasn’t all bad. And it’s hard to dispute that his plan for Newcastle as a ‘cultural capital’ is still being played out today.

- The era of regeneration and culture

The revived Quayside is a testament to the city’s determination to rebuild itself after the devastation of 1980s deindustrialisation. In 1991, Terry Farrell landed a commission to re-imagine Newcastle’s riverside. The fruits of the firm’s East Quayside masterplan are visible in the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Sage Gateshead and the Millennium Bridge. Given that these buildings, and the attendant bars and clubs, saw Newcastle’s image transformed from grim industrial outpost to party-mad culture hub, it must be Britain’s most successful and well-known regeneration project.

In 2000, Newcastle published Going for Growth, an ambitious, city-wide regeneration strategy, seeking to position itself as a competitive, cohesive and cosmopolitan city of international significance; this continued the momentum of the 1990s. And during this period, the two universities were also powering forward very successfully, expanding and creating interesting new buildings in their wake.

NewcastleGateshead’s standing as a cultural centre of excellence has in many ways been crystalised by their recent success in being chosen as the venue for the Great Exhibition of the North in 2018.

THE WALK

We set out from the station one early autumn evening, me having persuaded my (country) walking companion, Oliver, that we should stop off on our way north to the Cheviots for a night in Newcastle and an urban ramble. Uncharacteristically, he acceded easily so here we were, having read our Ian Nairn on Newcastle and full of expectation. We were not disappointed.

Newcastle Central Station is one of the great monuments of the early Railway Age. Opened by Queen Victoria in 1850, it was designed by John Dobson (you will hear his name many times); and the train shed was the first of the great multi-span arched sheds of the nineteenth century. Simon Jenkins gave it his top rating in ‘Britain’s 100 Best Railway Stations’.

We were soon reminded just how much we were in pioneering railway territory by a large bronze statue of George Stephenson, now somewhat inappropriately marooned on a traffic island in Westgate Rd. Stephenson stands with a rolled plan in hand. The four reclining figures denote an engineer, a blacksmith, a miner and a railway platelayer – all trades of particular relevance to Stephenson.

His famous locomotive Rocket was built in Newcastle in 1829, supervised by his son Robert at their factory in South St (two minutes south of here via Orchard St, now re-developed as the Stephenson Quarter). Several parts of the Locomotive Works have been restored, including the Pattern Shop, Boiler Shop and Coppersmith Shop and are available for public hire. The Rocket was preserved and is now on display in the Science Museum in London. There is talk of transporting it back up north for the 2018 Great Exhibition.

We were just debating whether to keep walking down Westgate St or head along Collingwood St when a young Geordie interrupted our map gazing. “Can I help; do you know where you’re going?” he asked. Now, the chances of that happening in London are about zero. Geordies are a friendly and chatty lot; they even created a society for it – the Literary and Philosophical Society – founded in 1793 as a ‘conversation club’ by the Reverend William Turner, and host to a long list of the intelligentsia of the era. Engineer and inventor George Stephenson showed his miner’s lamp here for the first time, and in 1879, when Joseph Swan demonstrated his electric light bulbs, the Lit and Phil building became the first public building to be so illuminated. The society is still thriving today, with over 2,000 members, and actor & comedian Alexander Armstrong is President (he comes from the northeast and is distantly related to Lord Armstrong).

The Cathedral Church of St. Nicholas’ 15th-century lantern tower dominates the skyline of the area. It served as a useful navigation point for ships in the Tyne for over 500 years. Formerly Newcastle’s major parish church, St Nicholas was given Cathedral status in 1882, the same year that Newcastle was made a City.

We loved the Old Post Office on the other side of the road, dating from the early 1870s and recently restored to its former glory by RIBA Enterprises.

Built between 1247 and 1250 during the reign of King Henry III, The Black Gate was the gatehouse to the Barbican. It strengthened the defences for the north gate of the Castle. The bridges could be closed quickly using counterweights and the front of the Black Gate could be sealed by a portcullis.

The Castle Keep is even older, dating back to 1080. The well is apparently nearly 100 feet deep, pretty much the height of the cliff on which the castle sits guarding the gorge, whilst the climb to the roof is well worth it for the views of the River Tyne and its famous bridges. Seven of the ten bridges between Newcastle and Gateshead can be seen.

Described on completion as the most perfect specimen of Doric architecture in the North of England, the Moot Hall, built in 1811, has columned porticos at the front and rear. In Ian Nairn’s words; “The Greek Doric portico of the Moot Hall has a monumental force that almost pushes you back across the road.” The Grand Jury Room has splendid views over the River Tyne and its bridges (if you can wangle your way in somehow – maybe you can pretend you’re looking for a wedding venue, which it now doubles up as, as well as being a court).

Just to the right of the Moot Hall is one of the most famous chares (stairs) that goes down to Sandhill by the quay – Dog Leap Stairs. In 1772 Baron Eldon, later Lord Chancellor of England, eloped with Bessie Surtees, the daughter of a local merchant who lived in Sandhill. Local folklore suggests they made their escape on horseback up these stairs. I really pity the horse! The villains in the film Get Carter (5.34″ excerpt)took the much easier option of running down it.

‘Chare’ apparently comes from the Saxon word ‘cerre’ meaning narrow place or turning in a lane. There used to be about 20 chares which led up from the Quayside in the medieval town (Dark Chare, Grindon Chare, Blue Anchor Chare, Peppercorn Chare, Palester Chare, Colvin’s Chare, Hornsby Chare, Plumber Chare, Fenwick’s Chare, Broad Garth, Peacock Chare, Trinity Chare, Rewcastle Chare, Broad Chare, Spicer Lane, Burn Bank, Byker Chare, Cock’s Chare and Love Lane). Saying these chares aloud is as pleasurable as hearing the shipping forecast, try it.

We were very tempted to head down the chare, which takes you to the swing bridge; but being ‘good scouts’ we resisted the temptation of irresponsibly losing 100ft in favour of the High Level Bridge and were glad we did because it gives you the best views imaginable and is rather atmospheric in a run-down sort of way.

But just before we get there, a word about the red brick ‘castle’ just to the east of the bridge, built on the site of Lord Armstrong’s mansion in the late 1890s. Originally occupied by the printers Robinson, it was subsequently taken over in 1963 by Turnbulls, a Newcastle-based ironmonger, who used it as a wholesale warehouse. In 2002 the building was redeveloped as luxury loft style apartments. In a way, the history of this site neatly symbolises the economic journey the city has had to make.

Completed in 1849 and designed by Robert Stephenson, the High Level Bridge was the solution to a complex problem, that of spanning 400 metres of river valley, 156 metres of which is across water. Officially opened by Queen Victoria in September 1849 (she seemed to get up to Newcastle a fair bit…was she ‘en route’ to her beloved Balmoral…), it was the world’s first dual-decked rail and road bridge. Famously, it was the scene of the red Jaguar car chase in the film ‘Get Carter’.

Completed in 1849 and designed by Robert Stephenson, the High Level Bridge was the solution to a complex problem, that of spanning 400 metres of river valley, 156 metres of which is across water. Officially opened by Queen Victoria in September 1849 (she seemed to get up to Newcastle a fair bit…was she ‘en route’ to her beloved Balmoral…), it was the world’s first dual-decked rail and road bridge. Famously, it was the scene of the red Jaguar car chase in the film ‘Get Carter’.

The High Level Bridge closed to traffic in 2005 for repairs and reopened in 2008, once again carrying trains on the higher level, but only ‘hopper’ buses and pedestrians below. Hurray. You probably could make more of it as a walking experience; on the other hand its faded-ness and dripping patches are part of its appeal, taking one back in time as well as across the gorge. It was the most ‘atmospheric’ part of the walk, the most ‘old’ Newcastle. Recently it’s become a popular spot for the ‘ Love Locks’ habit of attaching padlocks and throwing away the key as a sign of undying love for one’s partner, with many of the padlocks bearing scratched initials on them. Supposedly the trend began on the Pont des Arts in Paris at the start of the Millennium; many British city bridges have now been ‘infested’!

Love locks are undoubtedly divisive. Jonathan Jones, the Guardian art critic, has written that the practice is “as stupid as climbing a mountain and leaving a crisp packet at the top, or seeking out the most unspoilt beach and stubbing out cigarettes in the sand. Seriously. This is not a romantic thing to do. It is a wanton and arrogant act of destruction. It is littering. It is an attack on the very beauty that people supposedly travel to see.” I beg to differ. Here, at least, it helps brings a tired old bridge back to life and tells a thousand stories of connectedness, which after all is the essence of the bridge itself.

And now we find ourselves in Gateshead, padlocked of its own free will to Newcastle as part of the brand called NewcastleGateshead, the joint promotion of culture, business and tourism within the conurbation formed by Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead.

In swinging around towards the vast Sage building, we took a little road along the railway line that passes The Central, a Grade II listed building, built in 1856. Dubbed ‘The Coffin’ by locals because of its unusual shape, The Central is now fully restored to its Victorian splendour complete with a rooftop terrace. Local hero Sting apparently visited for an impromptu folk sing-along earlier in the year. The evening was organised by renowned Northumbrian piper Kathryn Tickell, who I have had the great pleasure of listening to. Catch her if you can. Here’s one of her songs on You Tube.

We also glimpsed the elegant spire of the Church of St Ann, built in 1767 in a dignified English Renaissance manner from designs by William Newton. Stones from the nearby old Newcastle town wall were used in its construction. It is a well-known landmark along the Gorge.

We felt we were creeping up unawares on Sage Gateshead, approaching it as we did from the land side. It was designed by Sir Norman Foster and opened in 2004. Sage Gateshead is an international home for music and musical discovery. It houses two main stages of acoustic excellence, a 26-room music education centre, a music information resource centre and lots of spots to eat & drink of course.

The design itself divides opinion – like marmite you either love it or hate it. Gavin Stamp in Private Eye savaged it as “a gigantic metal cliché which wrecks the scale and drama of the Tyne gorge …. looking like a giant slug or a big shiny condom. …. This big, bulbous steel sheath looms over everything, not least the Baltic Centre; its crude, tinselly form screams for attention and diminishes even the great high-level bridges”. Which is a bit harsh. Its setting allows it to be ‘big’ without necessarily being obtrusive; and its acoustically-smart form (each auditorium is a separate enclosure, sheltered beneath a roof that is ‘shrink-wrapped’ around the buildings) is more than justified by its rating as a top concert hall. According to Lorin Maazel, the Philharmonia’s Director of Touring, “The Sage Gateshead is in the top 5 best concert halls in the world”.

The space between the Sage and the Millennium Bridge is not so exciting. In the words of Jones the Planner: “Perhaps the biggest disappointment of the Quayside urban renaissance is the poor relationship of the new buildings to the water, and the dull paving and landscaping of the promenade compromised by traffic and at times frankly bleak. A design competition for new public realm here would be an awfully good idea.” Tick. This area is just appalling for such an important open space – and sadly, no signs that it’s ‘just temporary’, this seems to be the finished product.

Mind you, there ARE a couple of things to feast one’s eyes upon. First, The Baltic Mill . Surprising considering it was only ever intended as a flour mill and in fact wasn’t originally completed until the 1950s (if you guessed more 1930s, you can take comfort from the fact that the designs were first drawn up then, but building was delayed by the war). The mill closed in 1982 and fell into neglect. It triumphantly re-opened in 2002 after being converted into an art space by Ellis Williams Architects.

Mind you, there ARE a couple of things to feast one’s eyes upon. First, The Baltic Mill . Surprising considering it was only ever intended as a flour mill and in fact wasn’t originally completed until the 1950s (if you guessed more 1930s, you can take comfort from the fact that the designs were first drawn up then, but building was delayed by the war). The mill closed in 1982 and fell into neglect. It triumphantly re-opened in 2002 after being converted into an art space by Ellis Williams Architects.

Next, we made our way across the Millennium Bridge, which has very quickly stolen the crown of ‘iconic Newcastle view’ from the Tyne Bridge which had held the mantle up until then. On the far side, there is a list of when the gate will be ‘tilted’ to allow boats through. Also opened in 2002, the award-winning structure was conceived and designed by architect Wilkinson Eyre and structural engineer Gifford. It’s well worth taking a look at how the bridge tilts on YouTube;. Trip Advisor reviewers are uniformly enthusiastic, here is a typical comment: “I loved this bridge; I couldn’t stop taking photographs. It is a fantastic engineering feat and so pretty in the evening with its changing rainbow colours. Also, has benches to sit and admire the view. Stunning.”

The Quayside is full of interest. The area was once an industrial zone and busy commercial dockside and also hosted a regular street market. In recent years, as the docks became run-down, the area has been extensively redeveloped.

Just on the right we were tempted up some very elaborate steps, which represent the southern startpoint of Terry Farrell’s vision of ‘The Geordie Ramblas’, a pedestrian route from Gateshead, across the Millennium Bridge and all the way up to Newcastle University and the Cultural Quarter, eventually over the (not yet built) Botanical Bridge and into The Exhibition Park and green space. You can see the full route at: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/Journals/1/Files/2009/7/9/The%20Geordie%20Ramblas%20Newcastle.jpg What a fabulous idea to re-connect the various parts of the city, especially the various art galleries (the phrase ‘ramblas’ derives from the famous Las Ramblas pedestrian boulevard in Barcelona). There is a problem at the top of these steps, though. It basically comes out onto a very busy intersection with no obvious way across. Still work to do. The road ‘repelled’ us back to the quayside, which proved to be a much better choice.

On our right we then passed the post-modernist Law Courts; now, despite the fact I generally hate post-modernist buildings, I rather liked this one, especially the red brick ‘tower’ on the right side that feels very appropriate for this location! The Newcastle Law Courts building was designed by the local architectural practice of Napper Collerton. Construction began in 1984 and the building was completed in 1990. It was one of the first new buildings in the quayside redevelopment programme.

Make sure you look up King St, up a flight of steps to All Saints’ Church, according to Ian Nairn “one of the best of its date in Britain. It is one of very few oval churches, built in 1786 by David Stephenson.” It was de-consecrated in the early 1960s, much at the time Ian Nairn would have seen it; and sadly, after flooding a few years back is now on the ‘at risk’ register. Fingers crossed.

And the great Tyne Bridge looms ever closer into view. Completed in 1928, it was designed by Mott, Hay and Anderson, to the same broad design as their Sydney Harbour Bridge version, which was being built at the same time.

There is a silent movie from the era showing construction entitled ‘The Building of the New Tyne Bridge’ (1928). It is astonishing to watch the fearlessness of the stevedores, who became known as ‘the spiders’. There is also a clip of the opening of the bridge, by King George V and Queen Mary, who were the first to use the roadway, travelling in their Ascot Landau.

There is a silent movie from the era showing construction entitled ‘The Building of the New Tyne Bridge’ (1928). It is astonishing to watch the fearlessness of the stevedores, who became known as ‘the spiders’. There is also a clip of the opening of the bridge, by King George V and Queen Mary, who were the first to use the roadway, travelling in their Ascot Landau.

The ‘experience’ of the Tyne Bridge is at its most intense as we passed under it, with the roar of traffic on the roadway a 100 feet above, the base of the parabolic steel arch powerfully conjoined with the Cornish granite out of which the massive rectangular towers are constructed; and all across the steelwork, myriad rivets, in fact over three-quarters of a million in total, giving the structure an almost Lego-like appearance.

On the other side, we reach The Guildhall, once the heart of Newcastle’s government. It housed the council chamber, whose powerful members were drawn from the various trade guilds in the town. They were responsible for regulating each of the trades, rights, rules, apprenticeships and the quality of produce. There were around 50 Guilds established in Newcastle between 1215 and 1675. These included the Mercers (1512), Brewers (1583), Cordwainers (1566), Tallow Chandlers (1442), Barber Surgeons (1442), Felt Makers (1546), Upholsterers (1675) and Scriveners (1675).

Much of the present building is credited to the architect Robert Trollope who worked on it in the 1650s. But the semicircle of columns on its east side was built by John Dobson, to support a portico for a fish market (now filled in).

The iconic Swing Bridge was opened in 1876. It stands on the site of the Old Tyne Bridges of 1270 and 1781, and probably of the Roman Pons Aelius. It was necessary to replace the old Georgian Bridge as it prevented larger vessels from moving upriver.

We cut up the west end of the Guildhall, at which point we had a great view of the mediaeval Bessie Surtees House, dating back to the sixteenth century. Ian Nairn wrote of this part of the city: “(It is like) … a city within a city, with the exchange and some famous half-timbered buildings (such as Surtees House) that seemed to have skipped straight across the Baltic – no cosy oriels and godwottery, but tremendous horizontal bands of windows. Newcastle in the north-east and looks north-east; and Lübeck seems nearer than London.”

Then we swung around to the right and up the hill, this time under the railway viaduct carrying the line to Edinburgh; and doubling up as an ‘entry gate’ to Grainger Town, one of the most complete pieces of town planning in the UK, comparable to Edinburgh New Town or Bath.

Incorporating classical streets built by Richard Grainger, a builder and developer, between 1824 and 1841, some of Newcastle’s finest buildings and streets lie within the streets we have just entered, including Grainger Market, Theatre Royal, Grey Street, Grainger Street and Clayton Street. These buildings are predominantly four storeys, with vertical dormers, domes, turrets and spikes. Richard Grainger was said to ‘have found Newcastle of bricks and timber and left it in stone’. Of Grainger Town’s 450 buildings, an astonishing 244 are listed, of which 29 are Grade I and 49 are Grade II*.

Grey Street was described by Nikolaus Pevsner as “one of the finest streets in England”. Ian Nairn was bowled over too, describing it thus: “The precise quality is grandeur without pomposity: everything serious but not lugubrious, everything formal and firmly urbane but not oppressive. Because it is so unobtrusive it comes over the visitor gradually, then with a feeling of tremendous homogeneity: this is not an architecture of a few set pieces, but the spirit of a whole city.”

The photograph that he took at the time indeed shows a very classic street, with the ground floors generally intact in their original state. But in the process of much-needed renovation in recent years, something has been lost. There is now a series of dispiriting chain outlets (in quick succession Café Rouge, Subway, Marco Polo, Barluga, Browns, Blakes, Harry’s Bar, Costa, Carluccios, Greggs and Byron) that disfigure the street level and make it look like Anywheresville – making us cry out for the quirky, albeit expensive individuality of, say, Bath. Still, calm down, look up and look along and you will be fine – a bit like the advice to avoid sea-sickness really.

Really glad we accidentally took a left at Market St in search of an indie cafe and instead found the glorious Central Arcade, an elegant Edwardian shopping arcade built in 1906 and designed by Oswald & Son of Newcastle. The faïence tiles in the arcade were produced by Rust’s Vitreous Mosaics of Battersea and are a delight. And here we discovered the perfect antidote to all those chains – one of the country’s largest and most famous independent music shops, JG Windows, which has been trading in the arcade since 1908!

Over the years, JG Windows has welcomed many of the region’s music stars through its doors, from Bryan Ferry to AC/DC’s Brian Johnson. And Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler recounts how as a boy growing up in Blyth he would visit Newcastle to look longingly through the windows of Windows at his dream instrument – an expensive Fiesta Red Fender Stratocaster, just like Hank Marvin’s.

The origins of the shopping arcade can be traced back to Paris, where they first started to appear in the late 18th century. The narrow streets without pavements, crowded with horse-traffic, must have made shopping hazardous. An arcade provided comfortable, stylish and safe shopping away from the dirt and clatter of the street.

Arcades suited the British climate too. Perhaps the most famous in London is the Burlington Arcade built in 1818 to the design of Samuel Ware. Regency arcades also survive in Bath, Bristol and Glasgow (we pass many of them in our urban rambles). A second wave of arcade building from about 1870 to 1910 came in the age of iron. The Victorian imagination ran riot with the possibilities of wrought and cast iron: The County and Cross Arcades in Leeds are among the most flamboyant. Cardiff has no fewer than five arcades from this period (see our Cardiff ramble). In the 20th century, the concept grew into the multi-level shopping centre or mall. Shame about the quality of the finishes in most cases, compared to what you see in this stunning arcade.

Coming out the far end, Grey’s Statue rears up in front of us. Grey is a man we should be grateful to for two reasons, both adding to our lives but in very different ways. First, of course, the eponymous Earl Grey Tea was named after him; but perhaps more importantly, he was the politician who steered the 1832 Great Reform Bill through the House of Commons. The Act granted seats in the House of Commons to large cities that had sprung up during the Industrial Revolution and removed seats from the ‘rotten boroughs’, those with very small electorates and usually dominated by a wealthy patron. It was therefore of special significance to a city such as Newcastle. Erected in 1838, the statue was created by the sculptor Edward Hodges Baily, who was also the creator of Nelson’s statue in Trafalgar Square.

Newcastle City Library was built in 2009 and is the city’s main public library. The city’s central library has been on this site since Victorian times, with the original building demolished in the 1960s to make way for a concrete and steel structure, which never captured people’s hearts and was described by local TV presenter and author John Grundy as “a monstrous concrete blob”. It rapidly became unfit for the purpose of a modern public library and the one you see today was built. Better?! Let’s line them up side by side and see what you think:

The neighbouring Laing Art Gallery had originally been built as an extension of the old Victorian library and was left somewhat out of context following the demolition of the older building, with a blank brick wall facing towards the city centre. It was designed in the Baroque style with Art Nouveau elements. It was opened in 1904 and contains paintings, watercolours and decorative historical objects, including Newcastle silver.

We passed the Unite Building in John Dobson St. Liked this building, but can’t find out anything about it!

The new Baring wing of Northumbria University’s art gallery is simple and stylish. This is quiet architecture, not much more than a partially-glazed box fused onto one of the university’s core buildings. The only dramatic moment concerns the striking, elongated bronze figure and symbolic river, created by Nicolaus Widerberg, which faces St Mary’s Place.

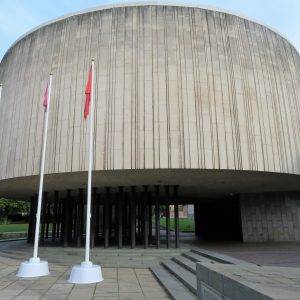

Next up one of my personal favourites in Newcastle, The Civic Centre. It is the main administrative and ceremonial centre for Newcastle City Council. Designed by the city architect, George Kenyon, the building was completed in 1967 and was championed by the infamous council leader T. Dan Smith.

It was formally opened by HM King Olav V of Norway in 1968, who was also awarded the Honorary Freedom of Newcastle to mark the historic, cultural and economic links the city enjoys with the people of Norway (that link with the Baltic again). Amongst other things, it entitled him to let his cattle graze on public land in the city (there is no record that he ever took up this kind offer).

The Nordic influence of the Civic Centre is clear, with walls of Norwegian Otta slate offset by the rich walnut and marble of the interiors, and the aged copper finishings of the exterior. A ring of heraldic sea horses circles the building’s trident-like tower, a nod to the city’s sea-bound heritage, with the impressive ‘River God Tyne’ sculpture by David Wynne cementing the link further.

As we started to walk up Claremont St, an earnest man in a yellow high vis jacket keenly beckoned us across to look at the entrance to a tunnel under the Hancock Museum. It turned out to be a seldom-opened access point to the Victoria Tunnel, a subterranean waggon way that ran from the Town Moor down to the River Tyne. It was built between 1839-42 to transport coal from Leazes Main Colliery in Spital Tongues to riverside staithes ready for loading onto boats for export. Full waggons descended the incline of the tunnel under their own weight and were rope-hauled back to the colliery by a stationary engine. The entrance we were at was one of those created when the tunnel was put into use as an air raid shelter in the Second World War.

The Hancock Building has been re-configured by Terry Farrell to link with a group of other buildings that together create the Great North Museum. We walked through the Hancock to the modern Devonshire Building. Completed in 2004, it is home to Newcastle University’s Institute of Research on Environment and Sustainability. In keeping with its function, the building was designed with state of the art systems that enable it to be environmentally sustainable.

Heading down Lover’s Lane, a key walking route for Newcastle University, we bumped into dozens of animated students on their very first day at the university; on one hand trying to stay calm and composed and on the other their brains trying to take in all the sights and sounds and new experiences. Ah, that wonderful in-between world called university where on one hand you need to take responsibility, and on the other, you need to be a little bit reckless.

Crossing the road to the park, Castle Leazes is the open space to our right and the settlement of Spital Tongues is on the far side of that. That’s a name that cries out to be explained – it is believed to be derived from ‘spital’ – a corruption of the word ‘hospital’ that is quite commonly found in UK place names e.g. Spitalfields – and ‘tongues’, meaning outlying pieces of land. Edward I gave two such ‘tongues’ of land to the St Mary Magdalene Hospital – hence ‘hospital tongues’ and eventually ‘Spital Tongues’.

Leazes Park (29 hectares, 72 acres) has a history going back to the 13th century when King John gave the land to townsmen of Newcastle to be used for grazing their cattle (‘Leazes’ meaning ‘meadowlands’).

In 1857, Newcastle Council was presented with a petition, signed by nearly 3,000 of the ‘working men of Newcastle upon Tyne and its vicinity’ that they should be granted ready access to some open ground for the ‘purpose of health and recreation’. From inception to completion it was 16 years before the ‘people’s park’ was opened in 1873. An ornamental bandstand was added in 1875, which proved to be extremely popular, drawing large crowds on a Sunday to enjoy the free musical entertainment.

The park continued to develop, with deer, aviaries, tennis, and croquet until the 1980s when it was in need of refurbishment. The refurbishment became possible when the park was awarded £3.7 million from the National Lottery in 2001. The restoration project was completed in 2004. One of the great virtues of Leazes Park is its proximity to the centre of Newcastle, with a hospital, university buildings and the football pitch on three sides of it; making it a popular place for lunch breakers, young families, students and visitors alike.

The Lort Burn is an underground stream that feeds the lake in the park. It used to flow through the centre of the city into the Tyne but was essentially used as an open sewer, particularly unpleasant since the meat markets backed onto it. In 1696 it was put underground, and in 1749 Dean Street was built following its course (hence the street name, from dene, which means a valley); as was its extension, Grey Street, in the 1830s.

Leazes Terrace is a Grade I listed building, built c. 1830 by Richard Grainger and designed by architect Thomas Oliver. The extreme juxtaposition with the St James’ Park stands is the first thing we noticed, but for some reason, it is exhilarating rather than being an eyesore. Leazes Terrace is now graduate accommodation for the university, and suffers a bit from not having a very lived-in feeling about it; and because the whole of the interior was completely re-done, a lot of the front doors don’t seem to be in use.

St James’ Park has been the home ground of Newcastle United since 1892. Throughout its history, the desire for expansion has caused conflict with local residents and the local council. This led to proposals to move at least twice in the late 1960s, and a controversial 1995 proposed move to the park we have just walked through, which fortunately was defeated by the Friends of the Park. The rather squashed location has led to the distinctive lop-sided appearance of the present-day stadium’s asymmetrical stands as the development of the east side of the ground was restricted due to the effect it would have had on the terrace. The roar along this road must be an experience on a match day and having a stadium right in the centre of the city is very exhilarating, somehow much more so than a characterless (albeit larger) edge of town location.

The Sir Bobby Robson Memorial Garden, just south of the stadium, was developed into a pocket park as a memorial garden for the life and work of Sir Bobby Robson, the football manager. Each of the five carved stones, by Graeme Mitcheson, represents an era of Sir Bobby’s life. A pleasant place to sit, I imagine this is a very popular meeting place on match days.

Newcastle’s Chinatown is a fairly recent invention, with Stowell St at its heart – the first Chinese business only moved there in the late 70s, but now the street is entirely made up of Chinese restaurants and shops. At the north end of the street, looking towards the football ground is the Chinese Arch, built in 2004 by Shanghai craftsmen, adding a dash of colour to this end of town, and is our route to the town walls.

The town walls were constructed during the 13th and 14th centuries to repel Scottish invaders. A special tax, or ‘murage’, was levied by the borough to pay for the construction. It was first levied in 1265, so it can be assumed that construction began soon after that date. The payment of murage continued for the next hundred years, so construction was probably not finished until at least the mid-14th century.

When completed, the wall was approximately 3 km long. It had six main gateways and seventeen towers as well as several smaller turrets and postern gates. In Eneas Mackenzie’s famous description: “the strength and magnificens of the waulling of this town far passeth al the waulles of the cities of England, and most of the townes of Europe.”

This part of the wall that we walked along is the best preserved in the city; much of the rest has been lost over the centuries, the first to go in the late 18th century being along the quayside, as it was regarded as “a very great obstacle to carriages and a hindrance to the despatch of business”.

The Morden Tower in Back Stowell Street was built in about 1290. Since the early 1960s, Connie Pickard has been the custodian of the tower and has made it a key fixture of Newcastle’s alternative cultural life. Countless memorable music and poetry events have taken place here. Basil Bunting, for example, gave the first reading of Briggflatts here in 1965. Notable others include Allen Ginsberg, Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney, Tom Raworth and Carol Ann Duffy.

Allen Ginsberg wrote of his visit: “Greeted at Newcastle Central Station by the most furious display of gnostic graffiti in the gentleman’s room walls that I had ever seen on the planet, I realized for certain that the bardic rituals of Morden Tower were not merely the property of youthful cognoscenti continuing traditions of old, but that the magic enacted in the Tower articulated the unconscious of the entire city slumbering in the mechanic illusions of the century.” So there you have it.

The Blackfriars Monastery dates back to the 13th century. During the Reformation, the friary was dissolved and the land sold to rich merchants. It was then leased to nine of the town’s craft guilds, to be used as their headquarters. The guilds’ meeting houses in Blackfriars were well used until the 19th century, which probably explains why the building has survived, unlike the other Orders that had monasteries in the city.

Charlotte Square was built in 1770 by architect William Newton. It was the first London-style housing development associated with a garden to be built in Newcastle. The square itself and its garden have recently been restored to create an attractive and fully functional public space. The i6 building in Charlotte Square, a hub for digital businesses, has received several design plaudits and is indicative of where the new employment opportunities lie in the city.

No city square would be complete without a modern square with a row of concrete balls in it and Waterloo Square is happy to oblige. In the words of the developer, Napper; “(The square) aims to create a viable and natural extension to the existing city centre and includes a high-density mix of residential, commercial, retail and hotel space along with a new dance college, all served by a new car park. The urban layout encourages the extension of established pedestrian routes across the new square and completes the link with the Discovery Museum and the western end of the city beyond.” Very ‘au courant’ in its design expression.

Finally, we reached the somewhat garish International Centre for Life, a science village where scientists, clinicians, educationalists and business people work to promote the advancement of the life sciences. It was designed by Terry Farrell (him again) and opened in 2000.The complex roof pattern relates to a leaf form, with a central spine and standing seam ‘arteries’ running off at angles, created out of copper.

We were very struck by the bit of the development that wasn’t new – the 1840s John Dobson-designed (him again too) Market Keeper’s House complete with clock tower, retained in the centre of the development. In the 19th century, this spot had been a thriving cattle market, handling 10,000 animals per week. The opening of nearby Central Station in 1850 gave the market a boost as animals could be cheaply transported by rail. The Market Keeper’s House originally served as offices for the Market Keeper and the Toll Collector on the ground floor, as well as accommodation for both their families on the upper floor.

A final treat for you if you love a bit of Gothic Revival. As we were heading back to the station we looked across the road to the spire of the Church of St Mary’s. Designed by the great church architect Augustus Pugin (of Houses of Parliament fame) and built between 1842-44, the church became the Roman Catholic cathedral for the northern district in 1850, reflecting the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy on a regular pattern to England and Wales. About 300 years after the nearby Blackfriars monastery had been dissolved!! Thus proving that everything really does come full circle in the end, including our walk!

DIRECTIONS

- Head out E from the station along Westgate Rd, then shortly Collingwood St, until you reach St Nicholas’ St

- Turn down St Nicholas’ St, crossing to walk past the west end of the cathedral, then across the Side along a pedestrian way to the Black Gate

- Pass through the fortifications, then under the railway viaduct, with the castle now on your right; swing around to your right and over the High Level Bridge

- Arriving on the Gateshead side, continue up the High Level Rd, then left along Half Moon lane, crossing the Tyne Bridge Rd to walk alongside the north side of the rail embankment along Brandling St and then across Oakwellgate

- Head down the side of the coach park to the SW side of Sage Gateshead and then take the service road along the south side, skirting around the building to the main entrance in the NE corner

- From here follow the route down to the Millennium Bridge, which you cross

- On the far side, take the quayside path all the way until you go under the Tyne Bridge

- Bear right down a passage when you are almost level with the Swing Bridge at the end of the old Guildhall, coming out almost opposite the Bessie Surtees House on Sandhill

- Bear right here, then left into Side which goes under the railway viaduct up Dean St, which segways into Grey St

- At Market St, turn left, then shortly right through the Central Arcade, coming out on the other side in front of Grey’s Monument

- Turn right along Blackett St, which segways into New Bridge St W; then turn left after the City Library into John Dobson St

- Turn right into Northumberland Rd just after the Unite Building, and turn left along a footpath just after the Northumberland Building into the main Northumbria University Quad

- Head W from here, joining St Mary’s Place, crossing and then passing in front of the Civic Centre

- Then head W, crossing the Great North Rd and heading into, then through, the Hancock Building to the blue Devonshire Centre behind it

- Turn left back into Claremont Rd, then right up to the roundabout, at which you turn left down Queen Victoria Rd

- Take the first right down Lover’s Lane (a wide footpath), which takes you past student accommodation and buildings; turn left at the end, heading south now towards the park

- Cross and head slightly left when you reach Richardson Rd to head through Leazes Park, walking around the right side of the lake to exit onto Leazes Terrace, with the Georgian terrace on your left and St James’ Park Football ground immediately on your right

- Walk along the raised walkway on the E side of the ground, then take the steep steps down to Strawberry Place

- Cross past the Chinatown Gate, then follow the town walls path right until the entrance into Friars St, passing Blackfriars and then following the street around to the right

- At the end of Friars St, take a left and then a right down Cross St to Westgate Rd

- Turn right, cross the road and head down the pedestrian Thornton St which segways into Waterloo St, taking the first right into Peel Lane, then walking south through Waterloo Square and back into Waterloo St

- Cross the busy Neville St into Marlborough St, shortly turning left into Times Square, then exiting by the north side east along Neville St and back to the start at the station.

PIT STOPS

Baltic Kitchen, The Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, NE8 3BA (0191 478 1810, www.balticmill.com)

Long Play Café, 48-52 Quayside, NE1 3JF (www.longplaycafe.co.uk ) Coffee and vinyl shop, where there is a collection of over 2,000 LPs and 1,000 45s to purchase.

Quay Ingredient, 4 Queen St, Quayside, NE1 3UG (0191 447 2327, quayingredient.co.uk) Just under the rail viaduct.

Quilliam Brothers Teahouse, Claremont Rd, NE1 7RD (0191 2614861, www.quilliambrothers.com )

Les Petits Choux, 11 Leazes Cres, NE1 4LN (0191 222 0349, www.les-petits-choux.co.uk )

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Central Arcade (NE1 6EG) the famous JG Windows music shop, and other shops.

Grainger Market (NE1 5JQ, end of Market St) www.graingermarket.org.uk

Grainger Market houses over 100 shops. As well as a wide range of fresh produce, fish & meat and bakers and cobblers, the market also offers also offers fabrics, take-away street food, jewellery, fashion and much more!

PLACES TO VISIT

Castle Keep, NE1 1RQ (0191 230 6300, www.newcastlecastle.co.uk) Climb the 99 steps to the top for a great view.

The Baltic Centre for Contemporary Arts, NE8 3BA (0191 478 1810, www.balticmill.com)

Laing Art Gallery, New Bridge St, NE1 8AG (0191 278 1611, https://laingartgallery.org.uk )

18th-20th-century British oil paintings and watercolours on display

Great North Museum, Barras Bridge, NE2 4PT (0191 208 6765, https://greatnorthmuseum.org.uk )

Victoria Tunnel. Guided tours can be booked at https://ouseburntrust.org.uk/victoria-tunnel/, but this needs to be done well ahead. Tours start at 55 Lime Street, opposite Seven Stories.

Discovery Museum, Blandford Square, NE1 4JA (0191 232 6789, https://discoverymuseum.org.uk ) A science museum and local history museum

Life Science Centre, Times Square, NE1 4EP (0191 243 8210, www.life.org.uk )

Fun for kids and adults with the planetarium, 4D Motion Ride and Science Theatre.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Walk: This 3 mile / 4.5 km walk explores Jesmond Dene – the upper section of the Ouseburn Valley which was landscaped by Lord and Lady Armstrong in the 19th century. The Dene’s steep wooded slopes provide a quiet haven both for people and wildlife alike. You can find a map of the route here.

Read: Nairn’s Towns by Ian Nairn, introduced by Owen Hatherley. The chapter on Newcastle starts; “Newcastle is a magnificent city for sheer excitement – the view that stops you dead half-way along a street, or the flight of steps that sucks you in like a vortex.”

Leave a Reply