The best of the countryside and the city? Or a planning cul-de-sac?

Letchworth is where the Garden City Movement began – the belief that cities can be planned to engender healthier, happier lives and offer the best of both town and country. The debate rages on to this day; but whatever side you take, Letchworth’s massive influence on the structure of the 20th century urban environment is incontestable and makes this walk a must.

BEST FOR…

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | The Cloisters, Spirella Building, Exhibition Bungalows, extensive residential areas. Download http://www.letchworthgc.com/galleries/see_letchworths_history for lots of interesting details about the houses that you will see along the route |

| Industrial Heritage | Spirella Factory |

| Modern (post-1918) | Town Hall, Broadway Cinema |

| ‘Green Spaces’ | |

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Broadway Gardens, Norton Park, Howard Park |

| Natural landscapes | Willian Meadow |

| ‘Fun stuff’ | |

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | David’s Bookshop Café |

| Quirky Shopping | The Arcade |

| Places to visit | International Garden Cities Exhibition |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Letchworth Food & Garden Festival (May), Letchworth Festival (June) |

City population: 33,249 (2011 census)

Ranking: not ranked

Date of origin: 1905

‘Type’ of city: Planned

City walkability (www.walkscore.com): 77/100 ‘Very walkable’

City status: It’s officially not, but it declared itself to be one nonetheless!

Some famous inhabitants: Laurence Olivier (actor), Michael Winner (film director), Magnus Pyke (scientist)

Notable city architects / planners: Ebenezer Howard, Raymond Unwin

Films/TV series shot here: World’s End (2013: various locations)

THE CONTEXT

The rapid industrial growth during the 19th century meant that British cities, especially London, were filthy, unpleasant places to live and bursting at the seams.

Ebenezer Howard, visionary and planner, started to envision a type of city which combined the best of both town and country. In his words, “There are, in reality, not only two alternatives – town life and country life – but a third alternative, in which all the advantages of the most energetic and active town life, with all the beauty and delight of the country, may be secured in perfect combination.” Out of this belief came the Garden City Movement and its first manifestation, Letchworth Garden City, which was founded in 1905. Its driving architectural principles were: lower density housing, zoned areas for industry, the separation of pedestrians and motor cars, plenty of green spaces and easy access to the countryside.

Letchworth was followed in 1920 by Welwyn Garden City and then the New Towns of the post-war years, which were all substantially influenced by the Garden City Movement.

THE WALK

How many times have I driven down the A1 and half noticed out of the corner of my eyes the sign to Letchworth? A name I have been familiar with for much of my life, but never until now decided to explore. It doesn’t have any big draws, no country house or theme park necessitating brown signs at every approach junction. Its everydayness is in many ways what strikes you most about it when you arrive.

There is nothing to indicate that this was possibly the most important town planning innovation of the twentieth century – a vision of a community with the benefits of town and country combined, providing a bold new alternative to the relentless expansion of London; and delivered on a scale and completeness that was unprecedented in Brisith town planning history.

Normally when you visit a city, you see the name of the city but seldom does anyone see the need to remind you it is a city. But not so with Letchworth; wherever you go you are reminded that it isn’t just ‘Letchworth’ that you are visiting, but ‘Letchworth Garden City’. Now of course it’s not really a city at all; no cathedral and a population only a little over 30,000 – the size stipulated by its founder as the ‘right size’ for successful communities, but only about a tenth of the size normally associated with a city. Maybe it’s this sense of self-importance which has led to commentators often being very sniffy about the merits of this urban experiment.

At the start of the twentieth century, Letchworth was just a little sleepy south of England village like thousands of others, with its church and village green; until the Garden City Pioneer Company acquired land around it and determined that this was to be the place for a brave new experiment in town and social planning.

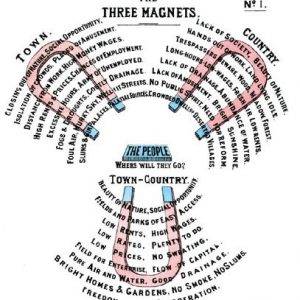

In 1898, the social reformer Ebenezer Howard published his ‘Garden Cities of To-morrow’ treatise, in which he advocated the construction of a new kind of town, summed up in his Three Magnets diagram as combining the advantages of cities and the countryside whilst eliminating their disadvantages. Industry would be kept separate from residential areas and trees and open spaces would prevail. The city was encircled by a ‘Green Belt’ (the first ever envisaged), which was designed as a girdle to prevent expansion, but also to enable self-sufficiency in food and to enable residents to remain ‘connected’ with the countryside. Letchworth promoted itself as a town for healthy living, and in its early years much was made of the sharply lower mortality rates than in cities. Howard’s ideas were mocked in the press, but struck a chord with many, especially members of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the Quakers.

For the concept outlined in ‘Garden Cities of To-morrow’ was not simply one of urban planning, but also included a system of community management. For example, the Garden City project would be financed through a system that Howard called ‘Rate-Rent’, which combined financing for community services (rates) with a return for those who had invested in the development of the City (rent). It also advocated a self-sufficiency in water and energy supplies, ideas that were partially realised and survived until the nationalisation of the 50s and 60s.

GETTING GOING

Shortly after we set out from Howard Park we spied the thatched building of the International Exhibition building on the right. Not quite the vernacular you expect in the middle of a city, more like a rural cottage, but a reminder that everything you see today will be just a little out of the ordinary, yet at the same time somehow deeply familiar. Here we took a look at the ‘master plan’ for Letchworth drawn up in 1905, a plan that exudes certainty about the ‘correct’ solution for urban dwelling. Remarkably, a substantial part of the plan (but by no means all) got implemented; and this is what makes Letchworth so notable in the history of town planning.

The other striking thing about the exhibition is the room to the right that shows the massive influence that the Letchworth experiment has had on the development of 20th century town planning throughout Britain. First was Welwyn Garden City just to the north, and then the New Town Movement which created more than 20 new or vastly expanded towns, of which Milton Keynes is the best known; all significantly influenced by Letchworth. Additionally, much of the re-construction work after the war took cues from Garden City thinking, especially the separation of car and pedestrian, re-drawn street grids and the complete re-modelling of core areas (see the Plymouth walk, for example), including the zoning of industry away from residential.

And the influence of Letchworth has spread internationally too. From its inception right up to the current day, there has been a steady stream of town planners and visionaries from around the world who have visited the exhibition to garner ideas and inspiration. Even Lenin apparently made a visit in 1907, to see a socialist utopia taking shape in practice. Notable international cities influenced include neighbourhoods in Boston (USA), Sao Paulo, Montreal, Melbourne, Adelaide and Cape Town; generally starting with the advantage of undeveloped land, where ‘new footprints’ are so much more practicable.

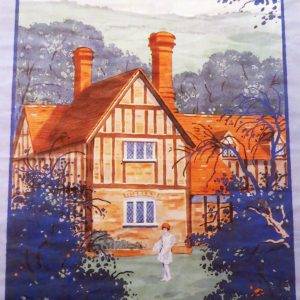

As we walked on from the exhibition, we passed though some very typical residential areas, redolent with memories of one’s own love for (or hatred of) the suburbs – houses in cottage-style vernacular, with thatched roofs, dormer windows, ‘olde worlde’ features such as rough-hewn wood and wine bottle glass windows, tiles, arts & crafts features, comforting hedges, echoes of ‘Merrie England’ – stylistic escapism writ large. The second thing that struck us was the size of garden and space between plots – the estates planned for 10-15 dwellings an acre vs. 35 for a typical urban location. So it is much more suburb than city street in look, especially as the day we visited it was also eerily quiet (my hunch is it’s like this most days). Much of what you see here you will see in thousands of suburbs up and down the country, if not to the same standards; for better or worse, this is where it all began!

Next stop for us was the outlandish Cloisters building, built in 1907 to a highly individualistic style. The word quirky could have been invented for this building!

The design reputedly came to Miss Annie Jane Lawrence, the founder and devout Quaker, in a dream. It consists of a large half-oval ‘open-air room’ called the ‘Cloisters Garth’, which features an open colonnade to the south and large glazed bays to the north. It was designed according to the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement, and was built using a rich palette of materials – grey Suffolk bricks, Purbeck stone, flintwork and vivid orange Suffolk tiles.

What you realise on closer inspection is that it was never completed – perhaps not surprising given that the building costs had soared to £20,000. You will notice bare blocks of stone inside and out and gaunt brickwork and unfaced mass concrete vaults. A grand ambition that was never quite realised – a good metaphor perhaps for the Garden City itself.

Originally built as an open-air school dedicated to Psychology, students were encouraged to study “how thought affects action and what causes and produces thought”. Through healthy outdoor living it was intended that the students would develop healthy minds. The building was also designed to hold lectures, conferences, drama and musical performances. Students were taught skills from the Arts and Crafts movement. They slept on flat hammocks lowered from the vaulting around the open Cloister Garth, the overall objective being a spirit of harmony and sociability. Communal meals were served on a great marble-faced dining table that stretched across a bay window on a raised altar-like dais.

In 1907 Howard led a tour of delegates from the 3rd Esperanto Conference in Cambridge to Letchworth. You can imagine they almost certainly travelled by train along the direct line from Cambridge, and walked along Broadway and then up the way we came to The Cloisters. Howard spoke (in Esperanto of course) on the Garden City Movement and Esperanto as allied efforts in the cause of international understanding and peace. Hope over practicality, the sense that things can be changed by planning and design; and that everyone can come together and live and communicate in new ways.

After the First World War, The Cloisters became known for its music and as a social hub for the Garden City – there were Sunday Organ Recitals, evening Promenade Concerts in the summer performed by the Town Band, orchestral recitals and a string band. The Sunday Concerts continued up until the Second World War, at which point the building was requisitioned by the Army, and fell into disrepair. It was rescued by the Masons in 1949, since when it has been the North Hertfordshire Masonic Centre.

Walking on past the Cloisters, back into Willian Rd and then heading south, all of a sudden we came upon a quintessential English village scene: a footpath meandering down across a meadow towards a pub, with a church and village green behind – a sudden escape back into the countryside and back in time to an earlier pre-suburban age.

It must also have been a popular route with the imbibers escaping the alcohol ban of the city centre, who would have tripped their way across the meadow, blissfully unaware that they were tramping over the country’s first ‘Green Belt’ designed to make them more ‘connected’ to the countryside. It certainly made them more connected to a good pint of ale or two.

After our brief foray into the countryside, it’s time to return to suburban bliss – but being Letchworth, along streets with names that determinedly evoke rural images – first we walked up Muddy Lane, then Spring Lane, before emerging on the formal splendour that is Broadway and the UK’s first roundabout; or at least that’s what it proudly proclaims, with a large placard in the middle of it; for Letchworth at least there is none of the roundabout reticence that most new towns show with regard to their traffic systems.

But is it really the UK’s first roundabout? In the plans of 1905 it was described as ‘Sollershott Circus’, and in that sense was similar to several other formal circuses around the country designed to create a sense of elegance and good living (e.g. the circuses in the middle of the Park Estate in Nottingham, which date back to the early nineteenth century).

Furthermore, in the year it was completed, 1909, there were only 53,000 cars registered in the whole of Britain, so two cars gyrating at any one time would have been a very rare event indeed! Even the day we went, there wasn’t much traffic compared to a normal roundabout. However, in favour of its claim to fame, it was envisaged in the master plan as an ‘intersection for gyratory movement’ – and critically, it was a public road, unlike the Park Estate in Nottingham, which was private. So perhaps we owe it to Letchworth to allow them this modest accolade.

Interestingly, it was replanted in 2013 for the movie ‘World’s End’, a science fiction comedy featuring Simon Pegg, Rosamund Pike, Nick Frost and a lot of Letchworth landscapes. Mr Burt, a town councillor, commented: “I hope it will become a tourist attraction and that people will want to come and see it as part of the film experience.” I don’t think he’d seen the movie at that stage, as it doesn’t do much to flatter Letchworth, with its cast of mostly befuddled middle-aged men and zombies being gruesomely de-capitated in quiet neighbourhoods.

The Broadway is perhaps the single most successful feature of the Letchworth design. It is a broad and elegant lime tree-lined avenue, nearly a mile long, with desirable detached houses along the southern half, and a civic area and station at the northern end. Its generous width is partly explained by the original plan to accommodate a tramway to Hitchin, but this was never built.

This northern end was intended to be the Town Square and there were to be a series of civic buildings ‘in the style of Wren and other masters’, but they were never built due to lack of funds. Nonetheless, it still works well today as an attractive open space surrounded by Lombardy Poplars and a fabulous fountain in the centre. Like the Cloisters, another unfinished piece of architectural business, but none the worse for that.

We walked through the rather dreary shopping area – all the shop fascias are designed in the same typeface and with a deep magenta background – another reminder of the rather controlled nature of the place. I suppose at least it doesn’t look like every other high street in the country with garish signage and identikit brands; but the shops here are not very impressive, more secondary chains than lively independents. The rural-looking station sign shouted out at us ‘Letchworth Garden City’ to persuade us, just in case we were still unconvinced, we are in a city!

And then finally we came across a building that is very city-like, The Spirella Factory, or ‘Castle Corset’ as it became known, constructed between 1912 and 1920 for the manufacture of corsets. This factory of course emitted no smoke, so it was ideal for the cleaner living of Letchworth. Mr Kincaid, the owner, claimed enlightened self-interest as the prime motivation for bringing the company to the Garden City:

“Letchworth is built according to a pre-arranged plan, not more than 12 houses built upon an acre, giving every cottage a good garden. These conditions make for efficient contented progressive workmen and women. A principle of Spirella’s policy has been to instil into its employees right thoughts, right methods of living, right methods of work, an appreciation of the vital needs of sunlight, of wholesome food for health and of congenial employment for happiness. The Spirella Company found itself in sympathy with every detail of the Garden City Movement which has found its best expression in Letchworth.”

(Mind you, he also apparently drove a hard bargain with the town, gaining a central location at half the price advertised.)

The Spirella Company was undoubtedly innovative in its choice of employee ‘perks’; these included a large social hall, free eye tests, bathrooms, a canteen, gymnastic classes, library, a choral society, bike storage and even capes issued on wet evenings to workers travelling home without a coat.

During the Second World War, the factory was also involved in producing parachutes and decoding machinery. It finally closed in the 1980s when corsets fell out of fashion, and was eventually refurbished and converted into offices. It is now Grade ll* listed and is home to a fitness centre, a conference/wedding suite and twenty or so businesses, including computer software & services, estate agents, financial companies and engineers. A productive next phase of the life of a notable building, reflecting the shift of our nation as a whole from manufacture to services.

The area that we reached next – Nevells Rd, Icknield Way, the Quadrant and Cross St – was the location of the nationally renowned Cheap Cottage Exhibitions that ran in 1905 and again in 1907 – a competition to build inexpensive houses. A £100 prize was offered to the best £150 cottage, which needed to include a living room, scullery and three bedrooms. Today most of the 101 houses originally built are still surviving and there is much of interest to look at.

The Exhibitions attracted some 60,000 visitors and had a significant effect on planning and urban design in the UK, pioneering and popularising such concepts as pre-fabrication, the use of new building materials, and front and back gardens. A sort of early version of Grand Designs. The competitions were sponsored by the Daily Mail (Lord Harmsworth, its owner, had been one of the original investors in the Garden City Pioneer Company), and their popularity was significant in the development of that newspaper’s launching of the Ideal Home Show – the first of which took place the year after the second Cheap Cottages Exhibition, and still continues to this day.

But whilst the 60,000 eager visitors no doubt appreciated what they saw, others rather turned their noses up at the experiment in a new style of urban living. In 1911, shortly after the homes had been constructed, Edward Thomas, war poet and novelist, happened to be passing through as he walked the whole of the prehistoric Icknield Way from Norfolk to the Berkshire Downs.

He wrote in the resulting book, ‘The Icknield Way’: “…The city resembled a caravan of bathing machines, except that there was no sea and the machines could not conveniently be moved.” (the pre-fabs presumably)

He went on: “On the right, two paths went off to some of the new houses of the Letchworth Garden City, and to a building gigantically labelled ‘IDRIS’. This was, I suppose, the temple of this city’s god” (it was in fact the IDRIS drinks factory).

The story of the name is really rather interesting. Thomas Howell Williams Idris, the company’s founder, changed his name to Idris, as he had been so struck by the beauty of the Idris Mountains in Wales, near where he had grown up. The IDRIS company was founded in 1880 to manufacture mineral and aerated water; and was relocated to Letchworth when the Garden City was founded (Idris was on the Board of the Garden City Pioneer Company, along with several other notable industrialists including Edward Cadbury and WH Lever, both famous for their own model towns, Bournville and Port Sunlight respectively). The IDRIS Company was subsequently merged with other drinks companies and the brand still exists under Britvic ownership, based now in Hemel Hempstead, another of the new towns.

In fact, contemporary criticisms of Letchworth seemed to flow thick and fast; on one hand, that Letchworth was a lifeless and banal urban sprawl; and on the other that it was idealistic and otherworldly. John Betjeman in his poem Group Life: Letchworth painted Letchworth people as earnest folks:

“Sympathy is stencilling,

Her decorative leatherwork,

Wilfred’s learning a folk-tune for

The Morris Dancers’ band.”

It also led Gorge Orwell, who lived in the nearby village of Wallington for several years, to his rather caustic but oft-quoted comment in ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’ (1937): “Letchworth attracts… every fruit juice drinker, nudist, sandal wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, nature cure quack, pacifist and feminist in England”.

One commonly-cited example of this is the ban on selling alcohol in public premises, most unusual for a British town. This did not stop the town having a ‘pub’ however – the Skittles Inn, advertised as ‘The Liberty Hall of the Letchworth worker’ but better known as the ‘pub with no beer’, which opened in 1907. It offered ‘fellowship, rest and recreation’ for workers, but all drinks served at the bar were non-alcoholic; Cydrax (a non-alcoholic apple wine), Bournville’s Drinking Chocolate, Tea and Sarsparilla (a root drink). In 1925, The Skittles Inn became The Settlement, a centre for adult education and local activities, which remains its function to this day.

The city-wide alcohol ban was finally lifted after a referendum in 1958, which resulted in the Broadway Hotel becoming the first public house in the centre of the Garden City. Several other pubs have opened since 1958, but even today the town centre has fewer than half-a-dozen (all visited by those befuddled middle-aged men in the World’s End film).

REFLECTION

So there have been many views about the whole Garden City Concept, both strongly for and strongly against. But there is no doubting that it was a major influence on much of the town planning in the twentieth century, for better or worse. Such a layout on such a scale was unprecedented – this is where modern, suburban England began.

And it is still talked about as much today as it ever has been. Although the prescription of a highly detailed ‘master plan’ is no longer in vogue, the concept of a ‘garden city’ very much is. The term ‘garden city’ has come to reflect more a lifestyle than a set of town planning rules – quality design, gardens, accessible green space near homes, healthy living, good walking routes, access to employment and local amenities.

Barely a day goes by without the ‘garden city’ concept being in the news. It remains the symbol of the search for a better way of urban existence. There has been much talk about ‘eco-towns’ to ease demand for low-cost housing. The towns – each to comprise around 5,000 homes – are intended to be carbon-neutral and will use locally generated sustainable energy sources. And in 2014, the government announced that a 15,000-home development at Ebbsfleet in Kent would be the first new garden city in a century.

In the same year the prestigious Wolfson Prize for Economics was awarded to David Rudlin, an urban designer, for his vision of garden cities as extensions to existing cities. His view is that Britain’s housing crisis could be largely solved by doubling the size of 40 towns and cities, including Oxford, Norwich, Reading and Stratford-on-Avon using garden city extensions, comprising circle-shaped developments set among parks and allotments and connected by trams to existing centres. These could provide homes for up to 150,000 people per town.

So the Garden City Movement remains very much alive and kicking, but fully-fledged births continue to remain elusive!

WALK DATA

Distance: 5.5 kms (3.4 miles)

Height Gain: none

Typical time: 1 ½ hours

OS Map: Explorer 193 – Luton and Stevenage

Start & Finish: Hillshott Car Park (SG6 1NY); the walk also passes the station (SG6 3AX)

Terrain: Almost all on pavements

THE ROUTE

- Head south from the Hillshott Car Park (SG6 1NY), crossing a small road into the second half of Howard Park; bear right just after the Bowling Green to join Norton Way South and pass the International Gardens City Exhibition (a thatched building) on your left. Cross over the roundabout (the intersection with Pixmore Way) and after 50 yards or so turn right into Meadow Lane, and then next left into Lytton Avenue, then left again along South View. You will pass the Quakers’ House on your left (they were a big influence on the town)

- At the end of South View, cross straight over into Cloisters Rd and follow this road until you reach the strangely-shaped towers of Cloisters; turn left, then right (S) into Willian Way, which you follow until its end

- Then keep heading south on a footpath signposted Willian and Cycle Route 12. Pass through a kissing gate on the left into a meadow and head down to All Saints’ Church

- From the pub/restaurant (The Fox) just this side of the church, head W along Willian Church Rd, bear right up Willian Rd at the junction with Wymondley Rd and then shortly you will see a gravel path on your right, heading N, which you take (also signposted Cycle Route 12). Follow this path N and you will reach the kissing gate you went through at Stage 3

- Just after that, the tarmacced path forks; you take the left fork (you had previously come in the other direction along the right fork); this path goes pleasantly through housing estates, then alongside St Christopher’s School playing fields, then in to Muddy Lane and the tennis club on your right until you reach the Baldock Rd

- Cross straight over, past the village stores and up Spring Lane. You will soon be rewarded by the impressive views north and south along Broadway, Letchworth’s most impressive piece of civic design. Head N and follow the Broadway all the way, past the fountains and shopping centre until you reach the station

- Turn left along Station Way, and shortly right along Bridge Rd, crossing the railway (the fabulous Spirella building on your left). Take the first right into Nevells Road, then the first left (N) along the quaint Quadrant

- On reaching Norton Common, take in as much or little of it as you have time and inclination for, and exit slightly further E and head south down Cross St, then left along Nevells Rd once again, with ‘The Settlement’ on your right

- On reaching Norton Way North, head right (south) and over the next roundabout into Norton Park. Go past the ponds, fountains and shop/toilets and you will be back at the car park.

A detailed Ordnance Survey map of the walk can be found at www.walkingworld.com , walk no. 7325

PIT STOPS

`The Simple Life Hotel‘ near the station was popular amongst early Letchworthians for its food reform restaurant and health food store, but alas it went many years ago.

David’s Bookshop Café, Eastcheap, SG6 3DE, just E of Broadway (Tel: 01462 684631, www.davids-bookshops.co.uk). And if you are hooked on Letchworth by now, there’s a very good local history section.

QUIRKY SHOPS

The Arcade: this recently-renovated historical 1922 covered shopping arcade (just NE of Eastcheap; SG6 3ET) is home to a selection of independent and specialist retailers, including a traditional sweet shop, jewellers, arts centre and café.

PLACES TO VISIT

The International Garden Cities Exhibition (296 Norton Way South), only a couple of minutes into the walk, has a good display of the history of the Garden City Movement and would be an ideal way of starting your walk. But note that it is only open on Saturdays or Sundays, or by appointment. Visit www.garden-cities-exhibition.com for details.

Leave a Reply