Attitude, character and great architecture old and new

Sheffield is a water city. It owes its name to the River Sheaf (‘a clearing by the river’), one of five rivers that run through the city; and it owes its historical wealth to the water mills, powering cutlery and steel industries from the fast and steep flows. The city’s layout was shaped by the topography of its seven hills and valleys. Its proximity to the Moors and many green spaces mean that you are never far from nature.

CITY CENTRE WALK DATA

- Distance: 7.5Kms (4.7 Miles)

- Height Gain: 30 metres

- Typical time: 2 hours

- Start & Finish: Sheffield Station (S1 2BP)

- Terrain: A steep climb up to the Cholera Monument, but otherwise easy going

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Ponderosa Park, Weston Park, Peace Gardens, Sheffield Winter Garden |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Sheffield Basin, River Don |

| Stunning cityscape | Cholera Monument |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Firth Court at the University (1905), Sheffield Town Hall (1897) |

| Industrial Heritage | Kelham Island |

| Modern (post-1918) | The Park Hill Estate (1946), University Library & Arts Tower (1966)

Look out for the excellent Sheffield City Centre Contemporary Architecture walking guide online |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Green City Café at Kelham, the Milestone |

| Places to visit | Kelham Island Museum, Millennium Gallery |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Sheffield Food Festival (May), Tramlines Music Festival (July), |

City population: 575,400 (2011 census)

Urban population: 640,720 (2011 census)

Ranking: 5th largest city in the UK

200-year population growth trend

- 1801 60,095

- 1901 451,195 (x 7.5)

- 2001 513,234 (x 1.14)

Date of origin: 8th century

‘Type’ of city: early Industrial city

City status: 1893

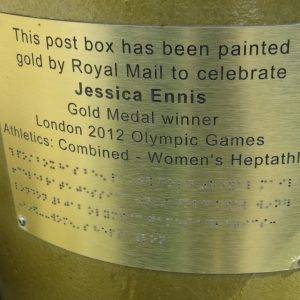

Some famous inhabitants: Malcolm Bradbury (author), AS Byatt (novelist), Bruce Oldfield (fashion designer), Peter Stringfellow (businessman), Sean Bean (actor), Jarvis Cocker (musician), Joe Cocker (singer), The Arctic Monkeys (band), Eddie Izzard (comedian), Michael Palin (comedian), David Blunkett (politician), Amy Johnson (aviator), Gordon Banks (footballer), Jessica Ennis (athlete), Naseem Hamed (boxer), Michael Vaughan (cricketer)

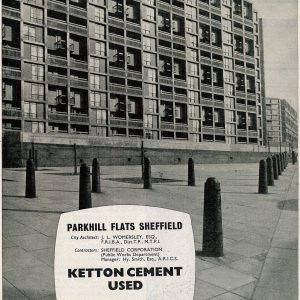

Notable city architects/planners: JL Womersley, City Architect (1953-1964). “They believed in the ability of city planning and architecture to improve the lives of ordinary people. The appointment of J. Lewis Womersley from 1953-64 was fundamental. His creativity and boldness of vision transformed Sheffield. Womersley’s response to the topographical challenges of Sheffield and restrictions of city boundaries was to build upwards, creating seminal works such as Park Hill and the Gleedless Valley estate.” Emma England, RIBA

Number of listed buildings: 1,167, of which 5 are Grade I and 67 are Grade II*.

Films/TV series shot here: The Full Monty (2001: various locations)

Famous quotes about the Sheffield:

“None of the big cities of England has such majestic surroundings as Sheffield.” Pevsner

“Modern Sheffield, a flourishing industrial city with over half a million inhabitants and a world-wide reputation, still retains many of the essential characteristics of the small market town of about five thousand people from which it has grown in the space of two and a half centuries.” Hunt, 1956

“Sheffield has more rivers than the Punjab and more hills than Rome.” Roy Hattersley

Estimated % of green space in the city (Eski): 22% (6th out of 10)

CONTEXT

During the 19th century, Sheffield became pre-eminent in steel production, especially cutlery. The crucible technique of making exceptionally high-quality steel was invented here by Benjamin Huntsman in 1852, and for decades it gave Sheffield the economic advantage over other steel producing cities. This and other local innovations fuelled an almost tenfold increase in the population within a hundred years.

But from being one of the north’s wealthiest and most successful cities, it was battered in the 70s by the decline in British steelmaking and the collapse of coal mining in the area. It was not until the new millennium that extensive redevelopment got underway, with steady economic growth and new service-based industries including hi-tech locating here.

The city nestles in a natural amphitheatre created by seven hills and the confluence of five rivers: the Don and its four tributaries the Sheaf, Rivelin, Loxley and Porter. Consequently, much of the city is built on hillsides with views into the city centre or out to the countryside. Nearly two-thirds of Sheffield’s entire area is green space, and a third of the city lies within the Peak District National Park. The BBC’s Countryfile magazine’s readers recently voted Sheffield as Britain’s ‘Outdoors City of the Year’ by a huge margin. There are more than 88 parks and 170 woodlands in the city and an estimated 2 million trees, giving Sheffield the highest ratio of trees to people of any city in Europe.

Even before the Industrial Revolution had begun, the villages around Sheffield were established as centres of industry and commerce, utilising the fast-flowing rivers and streams that brought water down from the Peak District. The valleys through which these flowed were ideally suited for man-made dams that could be used to power water mills, the remains of several of which you will see on the Porter Brook walk.

The city centre lies where these rivers and valleys meet. The city has expanded out along and up the valleys and over the hills between, creating leafy neighbourhoods and suburbs within easy reach of the city centre. Each valley that stretches out from the city centre has its own character, from the densely industrial Don Valley in the north-east to the green and cosmopolitan residential streets around the Ecclesall Road on the Porter Valley to the south-west.

THE CITY CENTRE WALK

Two or three times a year, typically on a Friday evening, I will meet long-time walking mate Oliver, who travels up from London, at some quaint Victorian railway station in some obscure (to us) part of the country on the way to a hiking weekend in the deepest, darkest countryside. To the casual observer, it wouldn’t seem peculiar that one evening this was taking place at Sheffield’s main station. After all, Sheffield is the gateway to the Peak District and you can be out on the moors in minutes by car.

But this evening was decidedly different. A walking weekend where the first waymark was actually the station concourse. As it was high summer and great weather, we decided to do some of the walk immediately and set out over the footbridge up to the Cholera Monument, set in a beautiful park of carefully trimmed lawns and a tree-lined avenue leading in from the road. It is quiet and secluded and yet right in the heart of the city, with fabulous views over it. The best possible place to get an overview of this great city and see its topography at first-hand.

George Orwell may well have been inspired by just this view when he wrote in Road to Wigan Pier (1936): “The town is very hilly (said to be built on seven hills, like Rome) and everywhere streets of mean little houses blackened by smoke run up at sharp angles, paved with cobbles which are purposely set unevenly to give horses etc, a grip.”

Another thing it had in common with Rome is that one of its biggest public buildings had to be constructed in a valley where there was enough flat ground, but also almost inevitably over a watercourse (here the River Sheaf beneath the main station; in Rome, tributaries of the River Tiber beneath the Coliseum).

The Cholera Monument is a sober reminder of just how perilous city life could be in the nineteenth century. With poor sanitation and crowded conditions, life expectancy was half what it was in the countryside. This monument was built as a memorial to the victims of the cholera epidemic that swept through the city in 1832. Preventative measures were still in their infancy and reportedly the dispensary at Sheffield University issued over 3,500 leeches that year, compared with a usual figure of around 100. 402 victims of the disease were buried in grounds between Park Hill and Norfolk Park adjoining Clay Wood. The monument was completed in 1835. It is, in Pevsner’s words “An earth-bound gothic pinnacle or spire”; with a plaque commemorating John Blake, Master Cutler in 1832 and himself a victim of the epidemic.

Walking North from here, we couldn’t miss the famous (or infamous depending on your take on its design) Park Hill Estate built in the ‘Brutalist’ style overlooking Sheffield. Park Hill was previously the site of back-to-back housing, a mixture of 2–3-storey tenement buildings, waste ground, quarries and steep alleyways (maybe this was the way George Orwell was looking). Facilities were poor, with one standpipe supporting up to 100 people. It was colloquially known as ‘Little Chicago’ in the 1930s, due to the high incidence of violent crime there. Clearance of the area began during the 1930s but was halted due to The Second World War.

Following the war, it was decided that a radical scheme needed to be introduced to deal with re-housing the Park Hill community. To that end, architects Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith began work in 1945 designing the Park Hill Flats. Inspired by Le Corbusier’s ‘Unité d’Habitation’, the deck access scheme was viewed as revolutionary at the time, most famously its ‘streets in the sky’ which were broad enough to drive a milk float along.

Even now, Sheffield’s inhabitants are split on the matter of Park Hill; many believe it to be a part of Sheffield’s heritage, while others consider it nothing more than an eyesore and blot on the landscape. Public nominations propelled it to the top 12 of Channel 4’s Demolition programme. The locally-raised Arctic Monkeys used it as a backdrop in the video to the song ‘The View from the Afternoon’ (2006). So love it or hate it, but it’s famous.

I was touched to see from this original poster above that the provenance of the cement used was seen to be a virtue – as it happens this Rutland cement works is still going today, and I can see it from my window as I write this blog. The works were founded by Frank Walker, a Sheffield builder, hence the connection. Ketton R &D was noted for its concrete innovations, notably a rapid-hardening cement (branded “Kettocrete”) and a waterproof cement product.

Following a period of decline, Parkhill has been renovated by developers Urban Splash (the same people who developed the Royal Dockyard in Plymouth, The Rotunda in Birmingham and the new Islington estate in Manchester). Naturally, their view of its potential is unremittingly positive:

“Park Hill is like no other place. Iconic is an overused term, but it really does apply to Park Hill. The Grade II* Listed Park Hill (the largest Listed structure in Europe) is a landmark on the Sheffield skyline atop one of the city’s seven hills immediately to the east of the mainline railway station and city centre. It already has character and we are creating a world-class landscape, inside and outside its walls.”

Moving on north, we crossed the traffic-encircled Park Square, a ‘front gate’ of sorts to modern Sheffield; not very edifying, but a major intersection point for Sheffield’s excellent tram system, which was built in the 90s, the previous version of which had been dug up in the 60s when the future was the car – a future that turned out to be a nightmare, as by the 80s the city was clogged with cars and buses. Today, about 15 million people use the tram every year, the centre is much less clogged and expansion plans are underway.

The next stretch of our walk, through Victoria Quays, across Lady’s Bridge and then along the Upper Don Walk to Kelham Island took us past several converted mills and reminders of Sheffield’s industrial past.

Victoria Quays was constructed in 1816–1819 as the terminus of the Sheffield Canal, which provided access to the sea via the Don Navigation. The quays were restored and redeveloped since 1992, we found them rather lifeless the day we were there. the most notable building is the Terminal Warehouse (1819), with its large stone-dressed arched openings, one forming a boat hole enabling goods to be hoisted directly to the upper floors. the Straddle Warehouse (1898) is also a lot of fun – due to limited space at the canal basin, and for the purposes of unloading grain, the warehouse was designed and built on stilts over the water, using a steel frame with concrete infill.

Reaching Kelham Island, the museum makes a very worthwhile stop. Formerly an industrial area, the island itself was created by the construction of a mill race fed from the River Don to serve the water wheels powering the workshops of the area’s industrial heydey.

The first thing we spotted was a massive Bessemer Converter, looking like a giant’s ladle, one of only three converters left in the world. The Bessemer process – the conversion of iron into steel – was invented and patented by Henry Bessemer in 1856. The egg-shaped converter was tilted down to pour molten pig iron in through the top, then swung back to a vertical position and a blast of air was blown through the base of the converter. Spectacular but dangerous flames and fountains shot out of the top of the converter. The converter was tilted again and the newly made steel was poured out. The first converters could make seven tonnes of steel in half an hour.

In 1858 Henry Bessemer moved to Sheffield and licensed his method to two steelmakers, John Brown and George Cammell, who both began to produce Bessemer Steel on an unprecedented scale. Others soon followed and within 20 years, Sheffield was producing 10,000 tons of Bessemer steel every week, almost a quarter of the country’s total output. The invention marked the beginning of mass steel production, as huge amounts could be produced in a relatively short time compared to crucible steel production. The steel was most widely used for the railways that were stretching around the world, and many bridges, including the Brooklyn Bridge in New York.

Moving west from Kelham Island, we passed through streets of deserted workshops which looked as if they were on the verge of being achingly fashionable, but had not quite had lift-off yet. It was in one of these disused workshops that the Human League first started to rehearse together. In 1978 they played their first live gig together at the Psalter Lane Art College (now Sheffield Hallam University). Sheffield has been a crucible for many famous pop bands including, amongst many others, Joe Cocker, Def Leppard, Pulp and the Arctic Monkeys.

Just before crossing the dual carriageway, we spotted The Globe Works, built in 1825 by the architects Henry and William Ibbotson for the edge tool manufacturers Ibbotson & Roebank. The Works are one of England’s oldest surviving cutlery and tool factories and were possibly the World’s first purpose-built cutlery factory. When opened the Works produced steel, tools and cutlery on the one site in an integrated process driven by steam power.

Then it’s on to the unlikely-sounding Ponderosa Park. During the second half of the 19th century the Port Mahon estate, comprising back-to-back houses, was built here in what had been open countryside. This housing stood until the 1960s when it was demolished, as part of a programme of urban re-development, and replaced by tower blocks and maisonettes, leaving a central area for recreation. This green space was christened ‘The Ponderosa’ by local children after the name of the 1960s ranch in the TV series ‘Bonanza’; and the name has stuck.

Crossing the Crookes Valley Rd, we entered into Weston Park, opened in 1873, and the first municipal park in the city. It was developed from the grounds of Weston Hall, which the Sheffield Corporation had purchased following the death of its owners, Eliza and Anne Harrison, daughter of Thomas Harrison who had made his money in saw-making in the late 18th century.

Architecturally, if you look one way you see the classic lines of the City Museum. Look the other way and you see The University Arts Tower, opened in 1966 and to this day the tallest university building in the country. English Heritage has described it as “the most elegant university tower block in Britain of its period”. In between there is the restored bandstand and an eight-metre high terra cotta column depicting youth, maturity and old age.

Then there are the statues and memorials: to commemorate Ebenezer Elliot, the Boer War and the First World War – lots to stimulate the mind and evoke the history of Sheffield.

The park is also home to one of the oldest weather stations in the country, Weston Park Weather Station, which has provided data on Sheffield’s weather since 1882. It was founded in response to a serious outbreak of diarrhoea which caused many deaths, particularly amongst young children. Scientists knew that there was a link between outbreaks of these kinds of disease and current weather conditions, but there was no weather station in Sheffield making regular readings. Without this data, doctors couldn’t predict or prepare for the outbreaks when they occurred. In 1881, the Department of Health lobbied Sheffield Corporation, and the following year the station was established.

In my opinion, Weston Park is one of the finest small parks in Britain, beautifully maintained and full of Sheffield history. A park that is really an Open Air Museum too. Oh, and as we left, we walked through the delightful 19th-century metal gates with terracotta pillars, designed by Godfrey Sykes. These gates have a rather unusual story surrounding them. Despite each weighing over a ton they were stolen in the dead of night in 1994. Fifteen years later, by sheer chance, they were spotted forming the gateway to a brand new house in a nearby village and, once authenticated by some blacksmiths who had undertaken repair work on them in the 70s, returned to their rightful place – so the gates you see today are back from a little journey!

Now it was time for us to head back to the Town Centre, past the grandly Gothic Firth Court on our left, one of the oldest and most distinctive buildings on campus. It was opened by King Edward VII in 1905, the same year that the university was granted its royal charter and officially came into being. It originally housed most of the university’s departments, but nowadays is solely its administrative centre.

Taking the underpass under Western Bank, we reached the newer parts of the university; the Students’ Union on our right, then a string of modern and interesting buildings as we headed east along Leavygreave Rd, including the ‘Information Commons’, a striking and innovative 24-hour space for study and information access. Further along, there’s the very distinctive ICOSS building, looking like something that has just emerged from the pod of Thunderbird 2.

Heading southwards from St George’s Church we walked down Regent St and across Glossop Rd, passing the north side of Devonshire Green. This used to be a neighbourhood of housing and small firms but was heavily bombed in the 1940 Sheffield Blitz. After the war the site was cleared and remained undeveloped, eventually serving as a temporary car park. In 1981 it was transformed into a public space with seating and pedestrian footpaths, and it was re-vamped again in 2008.

One fun thing to look out for as you walk past Barker’s Pool – the post box painted gold to celebrate Sheffield born-and-trained Jessica Ennis’ 2012 Olympic triumph.

The Peace Gardens, right in the heart of the city, just south of the gorgeous Gothic Town Hall, is a fabulous space. They were created in 1938, following the demolition of St Paul’s Church. Originally named St Paul’s Gardens, they were immediately nicknamed the ‘Peace Gardens’, marking the signing of the Munich Agreement in that year.

The eight cascades are a particular feature of the Gardens. These represent the flowing molten steel, which made Sheffield famous, and also the water of Sheffield’s rivers. They are dedicated to Samuel Holberry, who was the leader of the Sheffield Chartist Movement, which campaigned to extend suffrage and balance constituency sizes.

It’s sometimes hard to describe exactly why, but this space works in every way, as evidenced by the huge number of people who pause, relax and reflect here.

A few yards east of the Peace Gardens is the entrance to the Sheffield Winter Garden, the largest urban glasshouse in Europe; and home to more than 2,000 plants from all around the world. Twenty-one parabolic arches of laminated strips of untreated larch, together with slender purlins and glazing bars, create a fine glass house, the central section being 22 metres high.

We exited on the east side and took a look around the Millennium Centre, which houses art, craft and design. Then across Arundel Gate, through the attractive Hallam Square, a half amphitheatre-shaped plaza with seating and a water feature, and down the pedestrianised Howard St.

Half way down on your left, you can hardly fail to spot this piece of poetry by Andrew Motion :

“O travellers from somewhere else to here

Rising from Sheffield Station

and Sheaf Square

To wander through

the labyrinths of air

Pause now and let the

Sight of this sheer cliff

Become a priming place

Which lifts you off

to speculate

What if…

What if…

What if?”

No-one seems to have made their mind up yet as to whether this is a ‘great’ poem, but its setting is certainly arresting, and being on the side of Sheffield Hallam University, the challenge seems especially appropriate.

Then back to Sheaf Square in front of the station. The Cutting Edge water feature, weighing approximately 80 tonnes, was fabricated using Sheffield steel. Water is pumped from a large plant room under the main water feature to the crest of the sculpture from whence it flows over a levelled weir and down the polished face of the sculpture. The sculpture is cantilevered over a dished channel that collects the water and reflects light from dozens of blue LED lights set into the underside of the sculpture. The channel runs into a shallow pool at the ‘sharp’ end of Cutting Edge, simulating the quenching of a hot steel blade. People just love it, it works in every way, uplifting and intrinsic to connecting the station to the city centre.

Water, steel, art, people – what a fitting way to finish up.

CITY CENTRE WALK ROUTE

- Head south from the station down Cross Tunnel Street; and opposite Turner St take the footbridge across to the east side of the tracks. Cross the tramline and head up the hill towards Norfolk Rd and the cholera monument, which is clearly visible

- From the cholera monument you gain a great vista of the city; retrace your steps along Norfolk St, but this time retain height and head north along South St to the raised, traffic-encircled Park Square (the massive Park Hill Estate will be immediately above you on your right)

- Cross Park Square and exit onto the north side into Victoria Quays; exit under the road, proceed along Exchange Place and then across Blonk St Bridge. Turn left onto the Rive Don walkway and then cross back over at the next bridge (Lady’s Bridge) and proceed along the river on the west side. Head north west along the upper Don walk, passing under Corporation St, until you reach Kelham Island Museum

- Pass the Kelham Island Museum on your right (merits a visit). Head west to the end of Green Lane, cross the Pennistone Rd (dual carriageway), and bear half right up Infirmary Rd. Turn left up Montgomery Terrace Rd and enter Port Mahon Park (Ponderosa)

- Head up the path on the right hand side of the park into the second park; and as you approach the end of this park, climb some steps up to Bolsover Rd. Cross and enter Weston Park diagonally opposite

- Walk through Weston Park, keeping the lake on your immediate left; there is lots to look at in this park, maybe allow half an hour

- Exit at the south east end onto the A57. Turn left pass Firth Court and then go under the A57, with the Students’ Union, followed by the Hicks Building on your right. Bear right down Hounsfield Rd, then immediately left into Leavygrave Rd; cross the dual carriageway and continue along this road until you reach Regent St by St George’s Church

- Head down Regent St, head left into West St, then shortly right into Fitzwilliam St and left into Devonshire St. Pass Devonshire Green on your right. Devonshire St turns into Division St and after a few minutes you will reach the City Hall. Continue heading east along Barker’s Pool, then head right down Pinstone St and you will enter the fabulous Peace Gardens

- Walk east through the gardens and then shortly enter the amazing Winter Garden on your left; exit on the east side, past the Millennium Centre, then across Arundel Gate, through Hallam Square, down the pedestrianised Howard St and back to the station.

PIT STOPS

The Milestone, Pye Bank Rd, S3 8EQ (Tel: 0114 2728327, www.the-milestone.co.uk); gastro pub.

Green City Coffee, Unit 1 Kelham Square, S3 8SD (Tel: 0114 276 2803, www.greencitycoffee.co.uk)

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Undoubtedly Sharrow Vale Rd; a delightful shopping street, full of good independents and occasionally a Sunday market.

PLACES TO VISIT

Kelham Island Museum, Alma St, S3 8RY (Tel: 0114 272 2106, www.simt.co.uk) Full of interesting industrial heritage.

Weston Park Museum (Tel: 0114 278 2600, www.museums-sheffield.org.uk/museums/weston-park/home) archaeology and natural and social history exhibits, giving you lots more info on Sheffield.

Millennium Gallery, Arundel Gate, S1 2PP (Tel: 0114 278 2600, www.museums-sheffield.org.uk/museums/millennium-gallery/home). Here you can see some of Sheffield’s unique heritage, including the metalwork which made the city world famous, alongside contemporary art and design exhibitions; includes the city’s unique Ruskin and metalwork collections.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Download: The Modernist Guide to Sheffield, complete with fold-out map charting 32 buildings constructed between the 1950s and the early 1970s.

Leave a Reply