Grey but great

Author: Annabel Britton

The vast majority of this walk is alongside water – the river, the beach and of course, the harbour. It is one of few British cities where our maritime history feels so contemporary: Britannia may no longer rule the waves, but Aberdeen keeps an oily grip over Forties. This walk also explores other aspects of Aberdeen’s history, and of course its green spaces.

BEST FOR…

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Union Terrace Gardens, Duthie Park, Hazlehead Park, Seaton Park, Victoria Park, Westburn Park, Johnston Gardens, Cruickshank Botanic Gardens |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Dee, River Don, Aberdeen Harbour |

| Seafront | Aberdeen Beach |

| Stunning cityscape | Maritime Museum, Castle Hill |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1740) | King’s College, Mercat Cross, St Machar’s Cathedral, Kirk of St Nicholas, Bridge of Dee, Provost Skene House, Brig O’ Balgownie |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Bridge of Don |

| Victoria & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Marischal College, Art Gallery, Salvation Army Citadel, St Andrew’s Cathedral, St Mark’s Church, Central Library, St Mary’s Cathedral |

| Modern (post-1918) | Beach Ballroom, Sir Duncan Rice Library |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | CUP, Foodstory |

| Quirky Shopping | Retrospect |

| Places to visit | Maritime Museum, King’s Museum, Art Gallery |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Aberdeen International Youth Festival (Jul/Aug), Jazz Festival (March), May Festival |

City population: 196,670 (2012, National Records of Scotland)

Ranking: 39th largest city in UK

Date of origin: settled since the 6th century BC

‘Type’ of city: Ancient University

City walkability (www.walkscore.com): 96/100 ‘Walker’s Paradise’

City status: Granted its first charter in 1179, though it already benefitted from Royal Burgh status, given by King David I (1124-53). Old Aberdeen was incorporated into the rest of the city by an Act of Parliament in 1891.

Some famous Aberdeen people: Lord Byron (resident until the age of 10), BC Forbes (founder of Forbes magazine), Annie Lennox, Emeli Sandé (singer), Michael Gove, James Clerk Maxwell (mathematician, studied at Aberdeen)

Notable city architects / planners: Archibald Simpson (who now has the dubious distinction of having a Wetherspoons named after him), Alexander Marshall Mackenzie, John Smith

THE CONTEXT

Aberdeen lies on Scotland’s east coast, behind a long sandy beach stretching between the mouths of the Dee and Don. Over time these twin settlements, New and Old Aberdeen, edged closer to one another until they met and the city as we know it came into being.

So far removed from the British and Scottish capitals, the whole city looks eastwards towards the sea, as if turning its back on the rest of Britain: Aberdeen needs only the sea to survive.

That’s not really the case of course – Aberdeen graciously granted us with some of its famous granite, with which some of our most famous civic monuments have been built, including the Houses of Parliament, Waterloo Bridge and the Forth Rail Bridge.

The city kept most of the rest for itself, crafting buildings in a range of styles which gives it an appearance quite distinct from Edinburgh and Glasgow, where traditional sandstone was used to build its classic tenements, becoming a horrible black colour as it was gradually covered with smog. In contrast, hardy granite keeps its shine (the result of mica within the rock) – not to mention the fact that the freezing sea breeze would soon blow away any industrial fumes.

This exemplifies the difference between Aberdeen and the other two cities – far from the political and economical sphere of influence of Scotland’s central belt, Aberdeen is quite happy to quietly perch on the coast, quite comfortable with itself as a successful 21st century city.

THE WALK

Bridge Street thoroughfare from the station to Union Terrace gardens isn’t the most picturesque thoroughfare. Criss-crossing Victorian streets which could have echoed Edinburgh’s Old Town are instead the site of an Eighties shopping centre (whose days, I hope, are numbered). The Aberdeen of days gone by had much, architecturally, in common with the Scottish capital but I realised when I visited that the comparison is now impractical. So – close your eyes and pretend this bit isn’t happening. We’ll start properly at Union Terrace Gardens.

These gardens were opened to the public in 1879, when the municipal parks movement was well-established. Their sloping nature comes not from a natural amphitheatre as some locals would have it, but in fact the remains of demolished Denburn Terrace. This is a fitting symbol of this era in terms of urban development (and by no means one unique to Aberdeen in particular): the erosion of the private dwelling in favour of communal living spaces. The Gardens have been the object of very hotly contested development proposals over the past decade, with a £50 million gift from Aberdonian businessman Sir Ian Wood having been rejected because of opposition to his plans. The silver lining of this acrimonious discussion has been the engagement of local people in the planning of their own city; some 90,000 people voted in a referendum on the Gardens’ future.

But we can’t possibly speculate over what will or won’t happen – only survey the urban landscape we see before us! On the day I walked through the gardens, the terrace above them was bustling with visitors and traders at the Christmas Market while down below, in the sunken part of the park, were three enormous, white, inflatable bunnies. Don’t ask me why – I haven’t a clue.

Union Terrace Gardens (and bunnies) seen from Rosemount Viaduct

At the bottom we come out onto Rosemount Viaduct, this part of it a bridge over the dual carriageway Denburn Road – don’t look down. Immediately off the bridge, we turn back down Belmont Street. It must be a ‘nice part of town’ (read: where people spend their money) because there’s a Jack Wills. I chose to spend my pennies in CUP on Little Belmont Street (just round the corner) and found my money better spent on cake.

Reserves replenished and back onto Union Street, the city’s busy high street. From Diamond Street to Adelphi (which includes ‘our’ section) it is essentially a 19th century flyover, standing on arches crossing the older closes and wynds below. It’s almost as if the project, which nearly bankrupted the city, was intended to be a way for the great and good to get into town to go about their business without having to be confronted by the poverty below. Indeed, prostitutes had begun to ply their trade ever more brazenly in this area – not difficult to imagine with the harbour located so close by.

The ecclesiastical influence of St Nicholas’ Kirk – even closer – obviously didn’t do much to stop them! Nowadays, it gives its names to a more modern vice: a shopping centre.

Frankly, I don’t want to give that any column inches (pixels?!) so I’m going to pass onto Aberdeen’s most magnificent building, Marischal College; but first, a primer by a slightly more accomplished writer:

“No-one can dismiss Marischal College… Bigger than any cathedral, tower on tower, forest of pinnacles, a group of palatial buildings rivaled only by the Houses of Parliament at Westminster… you have to see them to believe them”.

John Betjeman

A section of the beautiful Marischal College

The thing is, now that you’ve read that, you’ll be expecting a spikier and greyer Taj Mahal. It is not quite that, dear reader, but it is arguably the most striking building in the city. The building’s current incarnation is in the neo-Gothic style, rebuilt at the dawn of the Victorian era. Its granite-grey façade is often considered to be the jewel – or rather stone – in Granite City’s crown. Indeed, it is the second largest granite building in the world, after an enormous palace on the outskirts of Madrid built for the King of Spain. Marischal College, in contrast, houses the city council.

The College was built as a civic alternative to King’s College, which had been founded by Papal bull before converting to Protestantism. The agnostic outlook, combined with closer integration with the city itself, led to an entirely different ethos at Marischal, which sometimes manifested itself in brawls between their students and those at King’s. The colleges were merged in 1860 into the University we know today.

Leaving the city centre now – en route to King’s in fact – we follow in the steps, probably, of many a student in days gone by. Judging by its current appearance, one would never guess that the Gallowgate was such an historically important thoroughfare – its significance in Medieval times was comparable to that of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile. Now, I know what I said about those comparisons, and this one is now useless as well. None of that heritage was preserved, and the Gallowgate now looks like a “run-down town in a forgotten end of the USSR” (as someone on the internet generously described it).

As we walk from here to the Old Town, the streets narrow and we get back to that Medieval heritage. Cobbled College Bounds strikes right through the middle of the main campus area; the first ‘landmark’ we get to is Powis Gates, to the left. It is now the gate to some Halls of Residence but it formerly heralded your entrance to the estate of a Scottish plantation owner. The family’s coat of arms is emblazoned on the back of the gates, including a rendering of three black men, which pays homage to the freeing of the family’s Jamaican slaves. How very gracious of them!

On the right is King’s College, Marischal’s Christian counterpart. The building is a composite of the Crown Tower and Chapel, built in 1500 with 19th century additions. The closed crown on top of the Chapel symbolises imperialism and, remembering it was built some 200 years before the Act of Union, alludes to the imperial ambitions of the Scottish Monarchy. Nowadays, it is the emblem of this historic university.

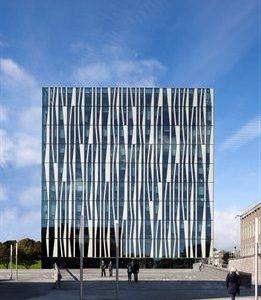

Another notable building in the area (though it isn’t quite on our route – strike off left up Thom’s Place to find it) is the Sir Duncan Rice library. Opened by Her Majesty the Queen in 2012, the building was designed by Danish architects Schmidt Hammer Lassen to evoke the ice and light of the North. Indeed, if you follow Aberdeen’s line of latitude to the East, you reach Denmark’s Northern tip. When I visited in December, the wintry contrasts of bright, freezing sun bookended by dark mornings and evenings felt more Scandinavian than British.

At the Northern edge of the campus we find the Old Town House; originally designated as the burgh’s administrative headquarters, overlooking the widened High Street which was used as a marketplace. Nowadays, there is a small university museum (though it was shut when I visited, and has varying reviews on TripAdvisor!).

Across the road, through a gate on the left, are Cruickshank Botanic Gardens. Unfortunately, they are partly obscured from the road by the aesthetically displeasing Cruickshank building, which houses the University’s Plant and Soil Science department. This should be a clue as to the gardens’ purpose – they are not there for the floral enjoyment of the tourist or city-dweller but for the students! This is very much a working botanical garden, and an important asset to the students and researchers who use it. For our purposes, it is a pleasant little stop-off, and maybe a place to eat your picnic.

Alternatively, you can unpack your sandwiches in the churchyard of St Machars Cathedral, a little further down the Chanonry. You may not be taking lunch next to the graves of any particularly notable people, but it is said that the left arm of William Wallace is interred somewhere within the walls of the cathedral, after he was hung, drawn and quartered in 1305.

St Machar’s was then a relatively new building; nowadays it is the product of the sequence of renovations and additions by the so-called ‘building bishops’, stretching from the 12th century to its completion in the 16th. The Normans kicked things off, though Alexander Kininmund II (1355-80) later demolished what they had built in favour of a series of granite towers and columns, which were in turn finished by Henry Lichtoun. So on and so on, there started a tradition of a new bishop coming in and completing his predecessor’s work until it took on its distinctive structure. What remains a mystery is how it took the bishops until the 15th century to fully cover the cathedral – I imagine Mass was a very chilly affair with half a roof!

Leading us down from the cathedral to the River Don is one of the city’s biggest green spaces, Seaton Park. The long stretch of the park along the award-winning flowerbeds is often used as a cut-through by students to get from halls to lectures. Further down the river we’ll encounter a different kind of wildlife; the mouth of the Don is a nature reserve.

The section along the river feels really rural, distant from the busy port. The path is often muddy here, but there are a few brilliant climbing trees to help you avoid the really sludgy parts! I didn’t indulge the temptation, but don’t take my lead – there’s a couple of opportunities for a scramble along toppled branches which suit everyone from beginners to the most experienced ‘climbers’ (i.e. adults who can’t resist the opportunity to be a big kid).

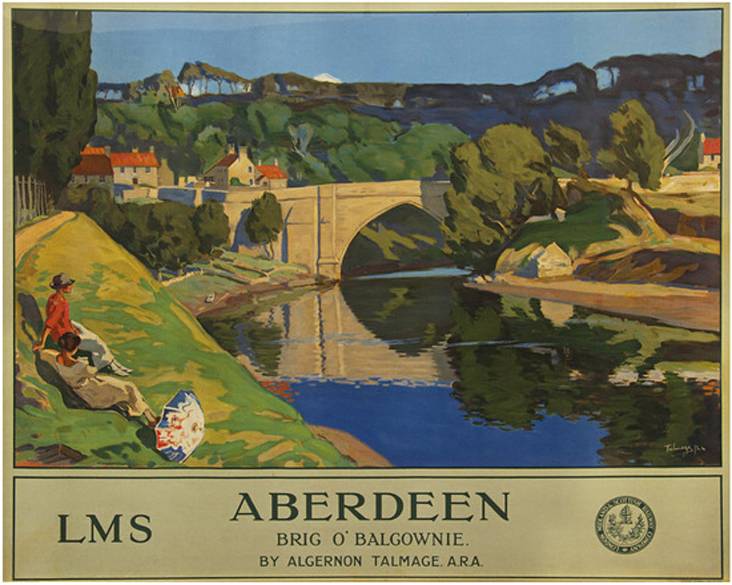

Spanning the river Don since 1320, the single granite arch of the Brig O’ Balgownie is very possibly Scotland’s oldest standing bridge. Though this may seem positively ancient, it is but a footnote in the history of the area, which has been settled for some 8000 years.

The Brig O’ Balgownie and the Don depicted in a poster for London, Midland and Scottish Railway by Algernon Talmage (1871-1939)

Walking the beach from Dee to Don is walking from Old Aberdeen to ‘New’ Aberdeen – though it is now one of the city’s older settlements. At the very foot of the Esplanade is the hamlet of Footdee, home of Aberdeen’s fishing community. The first recorded reference to ‘fittie’, as locals call it, was in 1398, though at this time it would have been located slightly further North.

Some four centuries later, one of the city’s key architects, John Smith, laid out a planned development to rehouse the fishermen and their families on a spit at the foot of the harbour. Smith’s original plan was of two squares of 28 houses, built in a regimented plan, intended to reflect the city’s neoclassical aspirations without disrupting the close-knit nature of North Eastern fishing villages. As demand for housing in the village grew, two new squares were added, gaps were filled in, extra storeys and extensions were added – as ever in Scottish residential areas, the houses began to take on tenement characteristics in an effort to avoid over-crowding. In 1880 the Council began to sell the houses to their occupiers and, since the home-owners now had the right to modify their properties as they wished, individuality could now be expressed within Smith’s planned template; herein lies Footdee’s architectural significance and interest.

Contrasting with the quiet, village-y nature of Fittie is the hive of industrial activity just round the corner. Aberdeen harbour, Britain’s oldest existing business, has been running for almost 900 years – since King David I of Scotland granted the Bishops of Aberdeen the right to levy a tithe on all ships using the port.

The spit of Footdee

It is striking to think that, since then, the harbour – and the industries it has supported – have survived threats from the Spanish Armada to the Blitz. However, neither a Spaniard sailor nor a German pilot would recognise it today: oil money has financed an almost complete renovation. It is one of the most modern ports in Europe, and an extension at Nigg Bay, down the coast, is in the pipeline (excuse the petroleum-based pun). With industrial decline being such a feature in Scotland’s urban spaces, it is wonderfully encouraging to see an historic British industry flourishing well into the 21st century.

the links of this rusty old chain were HUGE

The final straits of our walk take us back to an historic part of the city, The Green. It is also a brilliant example of how different factors, from the economic to the environmental, influence our urban spaces. However much urban planners and developers aim to shape our cities, their canvas is so very rarely a carte blanche, but in fact a space designed by all manner of circumstances. Boats or bombs, glaciers or guns – the most ingenious and the most depraved aspects of nature and humankind shape our cities.

This patchwork of lanes where the city meets the sea is the result of both destruction and creation. In fact, the majority of the route from this point onwards takes place on land reclaimed from the sea in the 18th century – it’s only as we reach the foot of Castlehill that we skirt the original seaside. You may notice that the hill no longer really deserves either part of its name: the castle was razed by Robert the Bruce in 1308 to prevent its recapture and fortification by the enemy. Legend has it that the city’s motto ‘bon accord’ is the secret password used by Scottish forces during this campaign. The hill was then lowered so it is now merely a few steps above sea level (though it still offers a good view of the harbour).

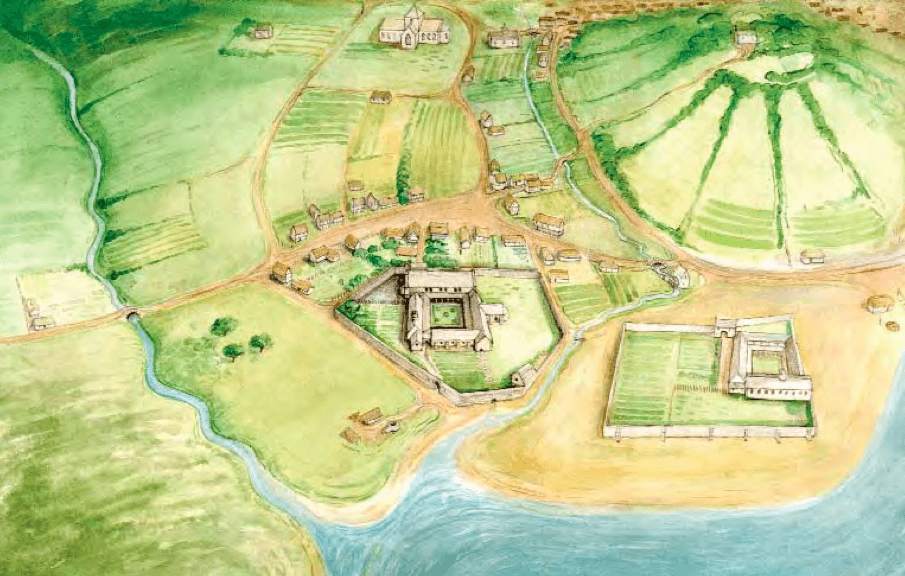

A bird’s eye view of this area as it would have been in 1450, by Jan Dunbar

The Castlegate, just above the hill, has been the centre of civic life in Aberdeen since that era: there has been a tolbooth on this site since the 14th century. The tolbooth, along with the mercat cross and the kirk, was an integral feature of the medieval Scottish burgh: the place where tolls and taxes were collected, and where the council held its meetings. Its current incarnation was built from 1616-29, attached to the Sherriff Court on Union Street – hence the inclusion of a gaol for convenience. It housed some 50 Jacobite prisoners during the Battle of Culloden (1746) but in the 21st century is home to a great little museum. Perfect to pop into if escaping the rain and you don’t particularly fancy the Wetherspoons next door…!

Should you be motivated to stop off at spoons (no judgement here – I enjoy ‘curry club’ and a cheap G&T as much as the next person), then at least you can do so in the knowledge that the premises are an elaborate Renaissance building, complete with Corinthian columns rendered in – what else – granite. Built in the Victorian era, it was formerly the North of Scotland Bank, by Aberdeen’s most famous architect, Archibald Simpson (1790-1847). Together with his rival John Smith, he created ‘granite city’ in a range of styles: Gothic to Renaissance, Tudor to Hanseatic. Though Simpson and Smith were often in direct competition to win clients, they respected each other’s work and collaborated – however indirectly – to create civic unity with their works.

The old North of Scotland Bank, now a pub named after its architect, Archibald Simpson

The street linking the municipal centre with the commercial hub of the harbour is Shiprow, whose cobbles we now tread. As such an important thoroughfare, it was home to the Lord Provost (Scots for ‘head honcho’) and as such Provost John Ross made his home here from 1710-12. Nowadays, a glistening glass frontage links it together with a former church in an eclectic cluster of buildings which make up the Maritime Museum.

On each level, the floor-to-ceiling window grants a magnificent vista of the harbour. The day I visited the sky was a bright blue, the kind which only appears on a chilly December day – a beautiful backdrop for the enormous, primary colour blocks of steel lurching in and out of the port. There’s more than enough inside to keep ramblers of all ages busy, too.

The architecture symbolises a lot of the Aberdeen story: the House, dating back to 1593 was the seat of the city’s executive, which governed seaborne trade at Aberdeen, the church representing the ecclesiastical influence exerted on the city while the shiny, new glass section has more than a whiff of oil money to it.

Distance: 12.5 kilometres (8 miles)

Height Gain: 135m

Typical time: 3 hours

OS Map: Ordnance Survey Explorer Map 406 Aberdeen & Banchory

Start & Finish: Aberdeen Train Station (AB11 5RG)

Terrain: Flat throughout, though the section along the Dee is fairly muddy.

THE ROUTE

- As you come out of the station, turn left (walking away from Sainsbury’s) and then right onto Bridge Street. Follow this until you cross Union Street, into Union Terrace Gardens.. Traverse the gardens, then turn right across Rosemount Viaduct. Turn right again, down Belmont Street (going back on yourself). Once back on Union Street, follow it left a few yards before crossing back through St Nicholas’ Kirkyard back onto Schoolhill. Follow this all the way down.

- Once facing Marischal College, turn left onto Gallowgate and follow it up to the roundabout, where you will take the underpass across to Mounthooly Way. Follow it to the junction with Kings Crescent and turn off left. Follow this road (which will become Spital, then College Bounds) into Old Aberdeen. You may wish to diverge into the St Peter’s Cemetery.

- Follow this road through the university, past the Old Town House, across St Machar’s Drive and onto the Chanonry, which will take you into Seaton Park.

- Go down along the long flowerbed to the very end and diverge to your left – you’re aiming for the white fountain. Go past this up to the river, which you will follow now (take the higher path) until you come to cobbled Don Street. Cross the Don on the Brig O’ Balgownie. Here you will once again skirt the river on a path (not the road) until you cross the river again on the King Street bridge.

- Turn left onto the Esplanade, following it up to the beach where you can cross onto the path. Follow this the length of the beach, all the way to the village of Footdee. At the very bottom you will go down some steps onto a path which will lead you to the very bottom of the harbour, the North Pier.

- Continue round the village onto Pocra Quay, then cross onto York Street. At the junction turn left onto York Place, then at the next one turn right onto Waterloo Quay.

- Walk all the way along Waterloo Quay, then Regent Quay. When you reach a junction governed by traffic lights, take Commerce Street off to your right. At the roundabout, turn left (it’s easiest to cross at the roundabout). A short way along, you will encounter some steps which will take you up to Castle Terrace. Turn left at the top of the steps, then follow the street round to the right until you find yourself in the pedestrianised Castle Street precinct (the Mercat Cross in the middle).

- Here, aim for the Archibald Simpson Wetherspoons on Union Street. Once just past the Tolbooth Museum, look for another turning called Castle Street almost opposite. Follow this down (where it will become Exchequer Row, then Shiprow) to the Maritime Museum.

- As you cross Market Street, Shiprow turns into Trinity Lane. Continue onto Exchange Street, where you have to turn right, then left, then left again to continue the walk onto Trinity Street. At Carmelite Street, bear left onto Guild Street and then walk up to the station to get back to the start.

PIT STOPS

CUP Café (9 Little Belmont St, Aberdeen, Aberdeen City AB10 1J, Tel: 01224 637730). Very chintzy and – dare I say – girly café in the city centre, serving more teas than you can shake a stick at, as well as plenty of cakes and brunch arrangements. This whole street is good for a little pick-me-up, and more manly alternatives can be found.

Foodstory (15 Thistle St, Aberdeen AB10 1XZ). Primarily vegan café with a health-conscious menu – though it won’t exclude those who need a hearty feed after a morning of rambling!

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Retrospect (9 St Andrew Street, Aberdeen, AB25 1BQ): Good value vintage shop in the middle of town whose owner goes by the moniker ‘Psychedelic Jim’!

PLACES TO VISIT

Aberdeen Maritime Museum (Shiprow, Aberdeen, AB 11 5BY, Tel: 01224337700): This fabulous museum tells the story of the city’s relationship with the North Sea and how it has evolved over time, and has a spectacular view of the harbour. Good for kids – interactive displays including the opportunity to pilot a real Remotely Operated Vehicle (a device for underwater exploration).

The Tolbooth Museum (Castle Street, Aberdeen, AB11 5BQ, Tel: 01224621167): The Tolbooth is one of the oldest buildings in the city, formerly a gaol but nowadays housing a small but perfectly formed museum about crime and punishment. The original stone cells have been wonderfully preserved, though the inmates are now talking models (though they are rather realistic, and made me jump about a foot in the air when they started talking).

23rd March 2016 at 1:46 pm

I want to go walking right now it looks & sounds wonderful .

Could I get my disability scooter along the path ? even some of the way would be good ,or maybe be better wth my walker? As you say plenty of watering holes along the way.

4th April 2016 at 7:43 pm

The muddier bit around the river might be a bit tricky, as would the cobbles near the university – I would probably stick to the city centre, or take part in one of our other rambles!