Green spaces here, green spaces there, green spaces everywhere…

This walk will simply amaze you for its incredible amount of green spaces. It is hard to believe you are close to the centre of the country’s capital, rambling through just about every type of green space imaginable.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 11.5 km (7.2 miles)

- Height Change: 72 metres

- Typical time: 2 ¾ hours

- Start: Finsbury Park Café (N4 2NQ)

- Finish: Alexandra Palace Station (N22 7ST)

- Terrain: Parkland Walk can be muddy, so wear appropriate footwear

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Finsbury Park, Parkland Walk, Waterlow Park, Highgate Cemetery, Hampstead Heath, Highgate Woods, Alexandra Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Highgate Ponds, River Fleet, New River |

| Stunning cityscape | Kenwood House, Alexandra Palace |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | Lauderdale House (from 16th C), Kenwood House (from the 17th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Highgate High St |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Highgate Cemetery (1839), Alexandra Palace (1873) |

| Modern (post-1918) | Cholmeley Lodge (1934), Holly Lodge Estate (1920s) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Kenwood Café, Lauderdale Café, Highgate Woods Café, The Grove Café @ Alexandra Park |

| Quirky Shopping | Highgate High St |

| Places to visit | Highgate Cemetery, Kenwood House |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Wireless Festival @ Finsbury Park (July); Alexandra Summer Festival (July) |

Some famous Highgate inhabitants: Rod Stewart (pop star), Andrew Marvel (poet), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (poet), JB Priestley (writer), Douglas Adams (author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy), Michael Faraday (physicist), Sir Ralph Richardson (actor), George Eliot (novelist), Max Wall (comedian) Christina Rossetti (poet) , Stella Gibbons (novelist), Kate Moss (model), George Michael (singer)…the list could go on.

Notable city architects/planners: Alexander McKenzie (Finsbury Park & Alexandra Park)

Number of Listed Buildings: Camden – 1,949, of which 56 are Grade I and 155 are Grade II*; Haringey – 282, of which 6 are Grade I and 21 are Grade II*

Films/TV series shot here:

Finsbury Park: Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Footage of Highgate Cemetery appears in numerous British horror films, including Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), Tales from the Crypt (1972) and From Beyond the Grave (1974)

Highgate: Truly Madly Deeply (1990), High Hopes (1989), Dorian Gray (2009)

Alexandra Palace: A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971)

Hampstead Heath: An American Werewolf in London (1981), The Monster of Highgate Ponds (1961)

THE CONTEXT

Highgate Village dates back to 1354 and was originally part of the Bishop of London’s hunting estate. From the 16th century onwards, impressive houses were built along Highgate Hill; and in Georgian times the area became highly fashionable as a country retreat for wealthy City workers, a demographic it still serves today. It’s the sort of place that when you walk through it you immediately feel ’this would be a nice place to live’ with a bustling high street and very varied architecture; the only problem being that you probably can’t afford it. It has an active conservation body, the Highgate Society, to protect its character and green spaces.

Highgate Wood and the adjacent Queen’s Wood are part of a cluster of ancient woodland sites that are located within a five-kilometre radius of Highgate Village. These woods all managed to escape development and are a vestige of a past landscape that comprised a mosaic of farmland, managed woodland and enclosed estate land for hunting.

By contrast, in the area to the east of our walk – Finsbury Park – the green space was created to try and alleviate the deprivation of an impoverished part of the capital, rather than being a reason to move there in the first place. Finsbury Park was created in the mid 19th century as a ‘people’s park, to create a ‘green lung’ and an escape from the unsanitary conditions in the surrounding slums. The petition to create it read: “A park on the borders of a district so large as the borough of Finsbury, and containing a dense industrial population of nearly half a million, is universally admitted to be a public necessity.” The story of Alexandra Park is not dissimilar.

And in the 20th century, we have had our own take on the importance of green spaces – and a lot have been to do with ‘re-naturing’ disused land – in this case, the Parkland Walk, which is an old railway that has been allowed to run wild. Just that act of doing nothing has created a space that is enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of people a year; and also has its very active protective society, the Friends of The Parkland Walk. Doing nothing is often better than doing something – plans were defeated in the 1980s to convert the old railway line into a relief road.

Three very different types of green spaces, from very different eras, but all serving our deep-rooted desire for some green space around us to escape into and relax in; and all brought about and preserved by a group of active and passionate local residents.

Think of all the type of green spaces you can…think really hard…and I don’t think you could come up with a walk that explores more different types of green space than this one:

- Public parks created by the Council – Finsbury Park and Alexandra Park

- A disused railway line – Parkland Walk

- Gardens bequeathed to the nation by a wealthy benefactor – Waterlow Park & Kenwood House

- Victorian cemeteries – Highgate

- Natural green space defended by the locals since the year dot – Hampstead Heath

- The source of a famous river – The River Fleet

- Ancient woodland – Highgate Woods

- Mediaeval water conduit – The New River

Getting the idea now?? This walk has the most amazing variety of green spaces, none better than each other, but each offering something different and in concert ABSOLUTELY astonishing!

THE WALK

The day we set out on this walk, a crisp and sunny Sunday morning, every Londoner north of Swiss Cottage seemed to be converging on Finsbury Park. Every road around it was blocked with traffic, the buses charging confidently down the bus lanes and the populace of London literally pouring into the park for their Sunday workout and pleasure.

In quick succession, we spotted a meditation group, a rope climbing group, an American football game about to kick-off (‘London Blitz’ is the home team), dads having ‘quality time’ with their kids, mums feeding their babies in the café, old friends meeting up for a chatter, dog walkers, a romantic couple canoodling on a bench; runners, more runners and yet more runners; speed walkers, dog walkers, cyclists, kite-flyers, footballers, frisbee throwers; a group of bearded young men discussing how best to cook pigeon; even someone reading a novel as they walked along… and of course us, urban ramblers. Wow, if you ever wondered what parks are for, just visit Finsbury Park (or for that matter any of the other 30,000 or so public parks in the UK) on a sunny Sunday morning.

Finsbury Park (46 hectares, 110 acres) was landscaped on the north-eastern extremity of what was originally Hornsey Wood, an area of woodland that was cut back further and further for grazing land during the Middle Ages.

In the mid-18th century, a tea room had opened on the knoll of land on which Finsbury Park is now situated. Londoners would travel north to escape the smoke of the capital and enjoy the last remains of the old Hornsey Wood. At the start of the nineteenth century, the tea rooms were developed into a larger building which became known as the Hornsey Wood House/Tavern. A lake was also built on the top of the knoll with water pumped up from the nearby New River. There was boating, a shooting and archery range, and probably cockfighting and other blood sports.

Starting in the 1830s, Londoners began to demand the creation of open spaces as an antidote to the ever-increasing urbanisation of London. In 1841 the people of Finsbury petitioned for a park to alleviate the conditions of the poor, and after a lengthy period of planning, re-naming and finally an Act of Parliament, the park was opened in 1869, to a design by Alexander McKenzie.

Alexander McKenzie was landscape designer to the Metropolitan Board of Works. He designed several public parks, including Alexandra Palace and the Victoria Embankment (working with Bazalgette). He wrote: “For some years past I have devoted much attention to the best modes of improving the British Metropolis with a view first, to the health of its dense population and next, in order to render it in somewhat more worthy of comparison with that of France than it is at present.” From Parks, Open Spaces and Thoroughfares of London (1869)

Driven by these noble ideals, he did a very fine job. But sadly the park fell into a state of disrepair in the second half of the twentieth century (in common with so many other parks across the land) and was only turned around in 2003 when it received a £5 million Heritage Lottery Fund Award; this enabled significant renovations including cleaning the lake, building a new café and children’s playground and repairing the tennis courts. Three cheers for the Heritage Lottery Fund – not only do they help create great British athletes, but they also help create great British parks where people can get out and exercise their minds and bodies.

The Friends of Finsbury Park are an active group, and the thing bothering them at the moment is the Wireless Festival, which closes off nearly a third of the park for several days; and in a wet year, such as 2016, leaves a muddy morass afterwards. In their words:

“The facts are sufficiently extreme to make this a good test case. A large amount of Finsbury Park is to be given over to the Wireless Festival – at least 27% by the Council’s own reckoning – and for a large amount of time including set up. Finsbury Park is an oasis of green in this very urban setting and is rightly valued by local residents who either have little or no outside space in their dwellings. The chaos caused by Wireless Festival last year was widely reported upon and sympathy is generally with the residents.”

Now the response of the council would be to say that the festival, along with other commercial activities, provides vital funds for the upkeep of the park – and if you consider what happened in the past when funds were scarce, you can see they have a point. But I am genuinely torn on this one – public access is also a vital issue. And it’s alarming how council budgets are being cut back at the moment. Bristol city council says its expenditure on parks will be cut to zero in 2019. Liverpool is investigating handing management of its parks to the private sector. Park space is now routinely given over to private companies to raise funds, often at the cost of access.

The Parkland Walk, opened in 1984, is a very different piece of green space – a disused railway line, now a linear green swathe stretching 5kms through North London from Finsbury Park to Highgate then (with an interruption) across to Alexandra Palace. The railway was constructed in 1867, with the short branch to Alexandra Palace being added in 1873. The line hasn’t seen a passenger for over half a century – the last passenger train ran in 1954, with freight traffic continuing until complete closure in 1971. The line was popularly referred to as the ‘Northern Heights’. On Google it looks like a snake-like river through the city, you would never guess its original purpose.

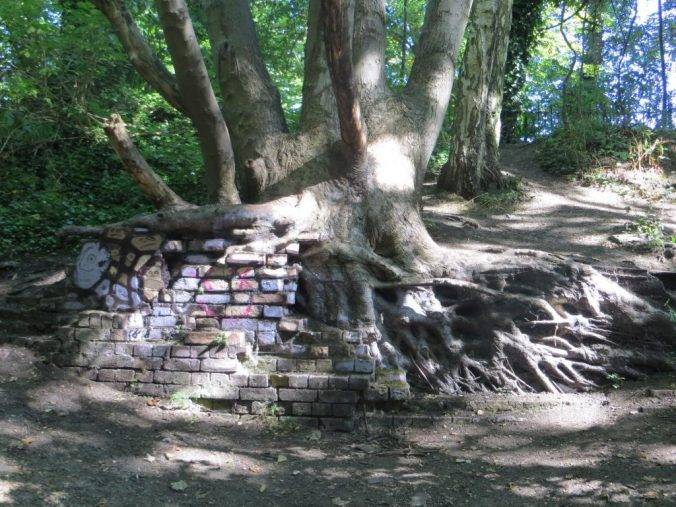

Now there was never a design for this stretch of green space – in fact quite the opposite – it has basically been left to its own devices; one day the railway company stopped maintaining it, and ever since then the vegetation has had free rein; self-seeded trees, brambles and buddleia, the ‘nectar station’ of choice for British butterflies. Famously, the buddleia spread up the rail arteries of Britain in the first part of the 20th century, carried on the locomotives or blown along in the slipstream, and providing an ideal rock and gravel habitat. Twenty-two species of butterfly have been recorded along this route, which you would be hard pushed to match in a deep country setting.

The result of this benign neglect is extraordinary – a genuine sense that you are in the depths of the country, but from time to time strange ghostly appearances of railways past – suddenly you are walking in the track bed with a platform each side, or you pass under a railway bridge, or an old railway building pokes out of the undergrowth. It is absolutely fabulous and full of runners and dog-walkers who feel the same way. During wet weather it becomes quite muddy, so some sturdy walking shoes are the order of the (wet) day.

The Cape Adventure Playground, which you see up on your left about half way along the route, typifies the modern style of green spaces. It is run by Islington Council, who describes it thus:“Cape Adventure delivers creative and exciting opportunities for children to explore nature and be adventurous with natural play in the outdoors making full use of Parkland Walk that surrounds the building… Come and be messy, climb wooden structures, build dens, try indoor arts & crafts and junk modelling, paint masterpieces, collect mini beasts, play sports & games or simply read a book and chill out in a naturally stimulating environment!!”

Again, the Friends of Parkland Walk is a very active group and well worth joining and supporting it if you are going to be a regular user of this linear heaven. In the late 80s, it was threatened by a plan to build a dual carriageway along its length. The threat was withdrawn following a vigorous and well-supported campaign by the Friends group.

Parkland Walk, Alice Stevenson, www.alicestevo.bigcartel.com

My one and only criticism of the Parkland Walk is I think it’s the wrong name – it bears no resemblance whatsoever to parkland, in fact it’s the very antithesis – how about ‘Wild Corridor Walk” or, let’s not reinvent the wheel, why not what it used to be called: “Northern Heights “ walk?

The old main road from London to York and Edinburgh had a notoriously steep section in Highgate Hill as it rose to the toll gate at the top of the ridge (the High Gate). Thomas Telford eased the problem in the 1820s by building the Archway Road as he improved the route from London to Holyhead and bypassed Highgate Village and its hills (very possibly the country’s first by-pass ). As we crossed this road we could just see the Archway Bridge down the slope; the cut was originally intended as a tunnel, but it kept caving in so a bridge was built instead; this is the second, a wrought iron construction erected in 1897.

WARNING: You will get house envy during the next phase of the walk, it’s almost inevitable, probably best just to give into it and enjoy…

The building that stood out for me most on this stretch of the walk was Cholmeley Lodge, just before we came out onto Highgate High Street; a Grade 2 Listed curving six-storied block of 48 flats, built in 1934 by Guy Morgan. It was controversial when it was built because of its flat roof (going against all the principles of roofs as rain deflectors) and a reinforced concrete structure. If you’re into your art deco, you will love this building.

Waterlow Park (10.5 hectares, 26 acres) is an absolute delight; one of my favourite parks, and very well maintained. I used to play tennis here with a good friend when I lived in London; and sure enough today a similar scene awaits, with players hurtling from one side of the court to the other for their lives and pride, just occasionally spraying a tennis ball out into the park at an impossible trajectory…

After Highgate was ‘discovered’ in the 16th century, the rich and famous started to arrive. Many of them built homes, with fine gardens, some in what is today Waterlow Park. They were attracted by the clean air and views over London, much as we are on our walk today. The plentiful water supply was another factor. Waterlow Park’s three historic ponds are still fed by natural springs (which feed eventually into the River Fleet).

Lauderdale House, which remains within the park, was the home of the Earl of Lauderdale in the 17th century. King Charles II is reputed to have stayed here with his mistress, Nell Gwyn. The house dates back to the 16th century, as does the garden, which is of interest to garden historians, being a very early example in Britain of a terraced garden.

The house where the metaphysical poet Andrew Marvell(1621-1678) is thought to have lived was also once within the park but is sadly no longer standing. One of Marvell’s verses, the last stanza of ‘The Garden’, is recorded on a bronze plaque in the formal garden, a reminder of the importance of ‘rus in urbe’ way back, the repose and calm of nature and its natural order:

More than likely you will get exactly this feeling as you pass through the park today; well at least providing a stray tennis ball doesn’t come your way…

From 1856, Sir Sydney Waterlow had also been living in a house within ‘the park’. He soon acquired the neighbouring properties, to create his own mini-estate; but he did not stay for long. The properties and gardens remained empty and deteriorating for some time until in 1889 he generously decided to present it to the London County Council as a public park and ‘a garden for the gardenless’. Much work was done to bring it back to order, but without losing its original features.

Sadly, just as with Finsbury Park, by the end of the 20th century the park was in poor condition; and once again it was ‘saved’ by Friends of the Park and by Heritage Lottery Funding (that source of funds comes up again and again in so many of our walks). The park re-opened in 2005. In 2016 the Friends of Waterlow Park celebrated the 125th anniversary of its opening. There was a Victorian-themed fête and descendants of Sir Sydney Waterlow helped launch a range of events reflecting the Park’s history. If you are searching for great British traditions, the British park and associated activities within them are surely some.

‘The Magnificent Seven’

London, in common with many other cities, was facing a major crisis as the population exploded in the first part of the nineteenth century. Inadequate burial space along with a high mortality rate resulted in a serious problem: there was just not enough room for the dead.

Parliament passed a statute to the effect that seven new private cemeteries should be opened in the countryside around the capital for the burial of London’s dead. These cemeteries were Kensal Green 1833, West Norwood 1836, Highgate 1839, Abney Park 1840, Brompton 1840, Nunhead 1840 and Tower Hamlets 1841. They have subsequently become known as ‘The Magnificent Seven’ (yes, for some reason, after the name of the 1960 Western).

In relation to Highgate Cemetery, an Act of Parliament was passed in 1836 creating The London Cemetery Company. Stephen Geary, an architect and the company’s founder, appointed James Bunstone Bunning as surveyor and David Ramsey, renowned garden designer, as the landscape architect. The sum of £3,500 was paid for seventeen acres of land that had been the grounds of the Ashurst Estate, descending the steep hillside from Highgate Village. Over the next three years, the cemetery was landscaped by Ramsey with exotic formal planting, complemented by the distinctive architecture of both Geary and Bunning. It was this combination that was to secure Highgate as the capital’s principal cemetery.

Sadly the cemetery became increasingly neglected during the second half of the 20th century as cremation became more the order of the day. It was not until 1975, when The Friends of Highgate Cemetery was formed with the aim of “promoting the conservation of the cemetery, its monuments and buildings, flora and fauna, for the benefit of the public as an environmental amenity” that work began to clear through the overgrown landscape and repair some of the memorials that had been damaged by vandals during the cemetery’s decline.

Since then an increasing amount of restoration and conservation work has been carried out. The Egyptian Avenue, Circle of Lebanon and the Terrace Catacomb, along with over seventy other monuments, have now been listed by English Heritage, with over double that number having had expert attention and maintenance. In 2011 the chapel interior was restored to its 1880s colour scheme and reopened for funerals. English Heritage has now listed Highgate Cemetery as a Grade 1 Park. Both sides of the cemetery remain open as active burial grounds with interments taking place weekly.

You are required to go on a guided tour if you wish to visit the West Cemetery, as it is very overgrown (which is part of its charm). But it’s more than worth it, especially for the Egyptian Avenue, an imposing structure consisting of sixteen vaults on either side of a broad passageway, entered via a great arch. These vaults were fitted with shelves for twelve coffins and were purchased by individual families for their sole use.

Unarguably the most famous interment in Highgate Cemetery is in the East Cemetery and is that of the philosopher Karl Marx who died in 1883. But there are lots of other famous graves too which we came across, including nearby the Marxist socialist, Ralph Miliband, father of David & Ed Miliband. And just up from there, the grave of the novelist George Eliot. A helpful map of the cemetery means you can search out famous heroes and heroines from the past. Or maybe you are just in the mood to wander around and read the fascinating inscriptions at random, telling tales of lives well lived and souls much missed.

The cemetery’s grounds are full of trees, shrubbery and wildflowers, most of which have been planted and grown without human influence. The grounds are a haven for birds and small animals such as foxes. The eco system is closer to the Parkland Walk than Waterlow Park – very au naturel, and being on a slope is incredibly appealing and atmospheric.

Crossing over from Highgate Cemetery to Hampstead Hath involves going through the rather curious Holly Lodge Estate, which has an almost eerie quietness about it and is gated, making us feel a little apprehensive about tramping through (but panic not, you are allowed to).

The estate dates back to the 1920s and has many interesting architectural features, including art deco, mock-Elizabethan timber beam and gable roofs with finials. Many of the apartments on the east side were originally designed for single women moving to London to work as secretaries and clerks in the burgeoning city, and maybe this was one of the reasons it was a gated community from the start – one of the earliest examples in this country.

Hampstead Heath (320 hectares, 790 acres) has been a playground for Londoners for more than a hundred years. When Constable painted it in the 1820s, it was still windswept high heathland to the north of London. However, the incursions of speculative builders and the extraction of sand for the construction of the new railways changed its face irretrievably during the nineteenth century. Early conservators fought back to retain the essential wild character of the Heath for posterity.

In 1865, the Open Spaces Society (OSS), Britain’s oldest national conservation body, was established to preserve our commons for the enjoyment of the public. Founder members included John Stuart Mill, Lord Eversley, Sir Robert Hunter and Miss Octavia Hill; and one of their first success stories was at Hampstead Heath, where they prevented both further extracting and building.

In 1871 the Hampstead Heath Act was passed, which included this clause: “The Board shall at all times preserve, as far as may be, the natural aspect and state of the Heath.” Earlier damage caused by sand excavation on either side of Spaniards Road across the Heath was rectified. At the same time, there was a belief on the part of the Metropolitan Board of Works Parks Committee, in favour of a natural appearance for the heath in preference to making it ‘prim or park-like’ (i.e. not like Finsbury Park or Alexandra Park, which were being developed at a similar time).

This stance was re-enforced in 1897 with the formation of the Hampstead Heath Protection Society (now called the Heath & Hampstead Society), whose objective was “the preservation of the original Heath in its wild and natural state and also the preservation of the natural characteristic features of later additions to the Heath so far as is consistent with their full enjoyment by the public.”

The Heath is now run by the Corporation of London, but the debate about maintaining it in its natural state is never over, as the recent hoo-ha over Highgate Ponds attests – people hate change, and everyone has a nuanced view as to what the ‘original natural state’ of a space might have been.

Arriving at The Heath is a sensational moment; your first reaction is that you have reached the ‘end of London’ and have been thrust suddenly into the countryside. Karl Marx, whose grave we had seen only a quarter of an hour earlier, visited the Heath regularly and loved walking here with his family. My uncle Alan lived on the other side of the Heath, and no visit to stay with him in London was complete without a walk across the heath to Kenwood House. He, like many local residents, must have crossed the Heath to and fro a thousand times or more – he seemed to know every nook and cranny, and it was very close to his heart.

We immediately come across Highgate Ponds, which were created as reservoirs 300 years ago to store the water of the River Fleet for drinking purposes. They have a wonderfully natural look, fringed by trees and grassy banks. For more than a century now they have been used for swimming; the men’s pond opened in the 1890s, the ladies’ in 1925, but the mixed pond is the oldest, having been in use since the 1860s.

The ponds have been the source of much recent controversy, a reminder of just how strongly people feel about ‘their’ green space. In 2011 the City of London announced a scheme that it said would improve the safety of the dams to guard against damage that might result from a very large, but rare storm hitting London. The proposals were challenged by a consortium of groups and societies collectively called “Dam Nonsense”, who felt that the scheme was disproportionate to the risk. But in the end the work took place, and although much earth was moved and footpaths temporarily closed, it got back to looking fine pretty quickly, as nature speedily re-encroached.

I mentioned that it is the River Fleet that supplies these ponds; one of its two sources is in the grounds of Kenwood House, where we are headed next. If lost rivers are your thing (I sense they might be!), you must get hold of a copy of the book ‘London’s Lost Rivers’ by Paul Talling; he also runs tours.

Maybe not quite at the level of excitement of finding the source of The Nile, I give you the start of The Fleet

Kenwood House dates from the early 17th century. In 1754 it was bought by William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, who commissioned Robert Adam to remodel it. Adam added the library, one of his most famous interiors, and added the Ionic portico at the entrance.

The estate has a designed landscape with gardens near the house, probably originally designed by Humphry Repton, contrasting with some surrounding woodland. There is also a new garden by Arabella Lennox-Boyd; and sculptures by Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Eugène Dodeigne.

After Kenwood our walk took us through the heart of Highgate, and past the north-western edge of Highgate School (those strange rooms with no back wall and internal buttresses are fives courts); this is perhaps where Sir John Betjeman, an alumnus and pupil of TS Eliot who briefly taught English there, got his love of grand Victorian buildings, the Highgate School Chapel being especially notable. He was a founding member of the Victorian Society and is generally credited with saving St Pancras Station. Of it, he wrote: “The plan to demolish St Pancras is a criminal folly. What the Londoner sees in his mind’s eye is that cluster of towers and pinnacles outlined against a foggy sunset, and the great arc of Barlow’s train shed gaping to devour incoming engines, and the sudden burst of exuberant Gothic of the hotel.” His success in saving the station is commemorated by a statue of him in the station concourse, erected in 2007 after the completion of major works. If you have sharp eyes you will be able to gain a distant view of St Pancras later in the walk.

Crossing the busy Archway Rd once again, we found ourselves in Highgate Wood (28 hectares, 69 acres); it dates back to the mediaeval period when it was part of the Bishop of London’s hunting estate. In the 16th-18 century, it was mainly leased out and coppiced for fuel and fencing. Remnants of wood banks dividing the areas can still be seen.

The entire wood was acquired by the Corporation of London in 1886 and publicly dedicated as ‘an open space for ever’ (love that phrase) under the Highgate and Kilburn Open Spaces Act. What a great act of foresight, for as soon as you are in them you feel you are in deep countryside, if only for a few minutes before you bump into reality again at the other side.

People seem to talk about life when they walk, especially here in the woods which somehow feel very private – this day we heard: “She can’t get pregnant; I think she cut her hair much too short; the problem is he’s feeling lonely; we haven’t got to exchange yet; I think we’ll need to get the plumber out” – people seem willing to share things on walks, big and small; your thoughts come out into the open, time for a good natter.

After the Wood, we re-join the Parkland Walk, this time heading directly towards Alexandra Palace. This vast, slightly cumbersome, structure perched on the hill dates back to 1873 and was designed to serve as a public centre of recreation, education and entertainment and as north London’s counterpart to The Crystal Palace in south London. In 1936 it became the home of the world’s first regular public ‘high-definition’ television service, operated by the BBC. Now it’s mainly used for exhibitions, conferences and music concerts, but the radio and TV mast is still in use.

Looking down from Alexandra Palace you get a true bird’s eye view of London – on the right, the Shard and the London Eye; in the middle, Canary Wharf and its surrounding escort; and now to the left Stratford’s high rises and the ArcelorMittal Orbit in the Olympic Park. So much has changed on London’s skyline and, to me at least, that adds to the interest of the view and the sense of a metropolis.

Alexandra Park (80 hectares, 198 acres) was originally designed by Alexander McKenzie (he also designed Finsbury Park) in 1863, as a park and pleasure ground. In 1900 an Act of Parliament created the Alexandra Palace and Park Trust, requiring the Trustees to maintain the Palace and Park and make them available for the free use and recreation of the public forever. The park now consists of a delightful mixture of informal woodland, open grassland, formal gardens and attractions such as the boating lake, cafés and the pitch-and-putt course.

Our walk ends here – but if you have the energy, we strongly recommend you take the New River Walk at this stage, either back to Finsbury Park where we started, or all the way to Sadler’s Wells where the river terminates. The New River Walk can be joined by skirting down the south-east side of Alexandra Park and exiting by Gate 3, then turn left.

But if you have run out of time, hop on the train at Alexandra Park Station and you will soon be back at Finsbury Park.

THE ROUTE

- Start at Finsbury Park Café, about 5 mins from either Manor House Tube or Finsbury Park (tube or train)

- Go west of the café and slightly south, and you will see a footbridge over the railway, which you take

- Almost immediately afterwards, take the path bearing right along the Parkland Walk, an old railway line – follow this for approx. 2.5kms

- Take a left turn down the slope, where there are some metal hand rails, into Northwood Rd. This is not a marked turn, so you will have to keep your eyes peeled for it. If you walk over the tiny Northwood Rd bridge (almost a tunnel), then you have gone a few yards too far!

- Walk up Northwood Rd, cross over the main road into Causton Rd; then left at the mini-roundabout up the hill into Cholmeley Park, then swinging round to the right and coming out on Highgate High St

- Turn right here, cross Highgate Hill road, and then shortly left into the delightful Waterlow Park

- Head SE, keeping the first lake on your right, then cross SW between the two lakes over the decorative bridge, and walk W along the southern side of the park, with Highgate Cemetery just to the south.

- Coming out of the park, turn left and you are immediately at the entrance to Highgate Cemetery; once you’ve had a look, continue heading south down Swain’s Lane until you reach Langbourne Avenue

- Pass through the pedestrian gate into Langbourne Avenue (don’t be shy) and head W, crossing Highgate W Hill, then continuing into Millfield Lane, which takes you onto Hampstead Heath

- Skirt north up the five Highgate Ponds (either side), west side marginally preferred, all the way up to Kenwood House

- As Kenwood House comes into close view, take a right where the mini-café is and follow this path round to Athlone House Gardens

- Skirt just to the south of the gardens, and head E, bearing left towards the exit at Bishopswood Rd, called The Orchard

- Cross Hampstead Lane into Bishopswood Rd, then Broadlands Rd, crossing North Hill into The Park (a road)

- Take the second left into Bishop’s Rd, then left at Archway Rd and shortly cross into the entrance to Highgate Woods

- Take a left fairly soon, heading due N through the woods, past the café, to reach the NE exit onto Muswell Hill Rd

- Head N a few yards, then you will see the entrance back onto the Parkland Walk, in Cranley Gardens; descend to the track bed and head E to Alexandra Palace

- Walk along the main terrace of Alexandra Palace itself and enjoy the amazing views; then continue heading E, keeping the road on your right, passing a fountain and eventually coming out just in front of Alexandra Station and onto South Terrace

- Swing round to the left, slightly uphill, and you will very soon see a footbridge to Alexandra Palace station, the end of your journey.

PIT STOPS

Finsbury Park Café, Boating Lake, N4 2NQ (07715 647295, www.finsburyparkcafe.co.uk)

Lauderdale Restaurant, Waterlow Park, Highgate Hill, N6 5HG (020 8348 8716, www.lauderdalehouse.co.uk). A gem of a café.

Mobile Cafe, Highgate cemetery – damn fine coffee, and a pain au chocolat!

Mobile Cafe, Highgate cemetery – damn fine coffee, and a pain au chocolat!

The Brewhouse Café, Kenwood House, NW3 7JR (020 8341 5384) popular café, but aroused much local ire back in 2014 when it threatened not to open until 10 am each day – the plan was defeated.

The Pavilion Café, Highgate Woods, N10 3JN (020 8444 4777) Wisteria-clad, great setting in the wood and a beautiful outdoor area.

The Grove Café @ Alexandra Park, N22 7BA (020 8883 5903) Friendly, quirky feel. A recent reviewer commented; “Fab café run by super friendly Italian Cirio and family and friends. Lovely location with the green of Alexandra Park right outside.”

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Highgate High St (N6 5HX)

PLACES TO VISIT

Furtherfield Gallery, McKenzie Pavilion, just south of the Boating Lake, Finsbury Park, N4 2NQ (http://furtherfield.org) occasional exhibitions, check website. London’s first gallery for networked media art.

Highgate Cemetery, Swain’s Lane, N6 6PJ (020 8340 1834, www.highgatecemetery.org) At the very least you must visit the east side (£4 admission); and if you have the time take one of the regular west side tours, which last an hour (£12, including ticket to the east side). West tours can be booked at http://highgatecemetery.org/visit/cemetery/west

Kenwood House, Hampstead Lane, NW3 7JR 9 (0370 333 1181, www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/kenwood/ Free entry and the chance to see a Robert Adam masterpiece.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Read: ‘The Magnificent Seven’, London’s First landscaped cemeteries, by John Turpin & Derrick Knight

Read: ‘London’s Lost Rivers’ by Paul Talling; he also runs tours.

Join: The Victorian Society

Leave a Reply