Weegie Wonderland: a flourishing city

Author: Annabel Britton

This walk delves right into the Glasgow story. Social and economic circumstance has shaped so much of this city, it’s almost one of the most perfect canvases for an urban ramble one could wish for!

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Glasgow Green, Necropolis, Botanic Gardens, Kelvingrove Park, Bellahouston Park, Pollok Country Park, Queens Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Clyde, Forth and Clyde Canal, River Kelvin |

| Stunning cityscape | Necropolis |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | St Mungo’s Cathedral, Provand’s Lordship |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | George Square, Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | City Chambers, Glasgow School of Art, Scotland Street School, Queen’s Cross Church, St Vincent Street Church, Holmwood House, Templeton on the Green, Garnethill Synagogue |

| Modern (post-1918) | Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow Science Centre, SSE Hydro |

‘Fun Stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Willow Tearooms, Ashton Lane, Drygate Brewery, Òran Mór |

| Quirky Shopping | Byres Road and around the West End |

| Places to visit | Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art, People’s Palace, Kelvingrove Museum & Art Gallery, Riverside Museum, Scotland Street School Museum, Tenement House, The Mackintosh House |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Celtic Connections (Jan), Glasgow Film Festival (Feb), Glasgow International Comedy Festival (Mar), Glasgow Arts Festivals (Apr), Southside Fringe and Film Festival (May), West End Festival (June), Pride Glasgow (Jun), Glasgay! (Nov) |

City population: 598, 830 (2011 census)

Ranking: 4th largest city in UK

Date of origin: 6th century BC; University founded in 1451

‘Type’ of city: Industrial

City walkability (www.walkscore.com): 96/100 ‘Walker’s Paradise’

City status: Granted in the 18th century by dint of ancient usage – in Scotland there is no correlation between the presence of a cathedral and city status. Legally designated as the ‘City of Glasgow’ following the Local Government (Scotland) Act in 1973.

Some famous Glasgow people: John Barrowman (actor), Frankie Boyle (comedian), Kevin Bridges (comedian), Gerard Butler (actor), Peter Capaldi (actor), Billy Connolly (comedian), Lorraine Kelly (television presenter), James McAvoy (actor), Duncan Bannatyne (entrepreneur), Twin Atlantic (band), Belle & Sebastian, Primal Scream, Franz Ferdinand, Mark Knopfler, Paolo Nutini, Mogwai, Simple Minds, Texas, Midge Ure, Wet Wet Wet, Gordon Brown, Sir Menzies Campbell, George Galloway, James Keir Hardie, Nicola Sturgeon, Sir Alex Ferguson, Charles Rennie MacKintosh (artist)

Films/TV series shot here: World War Z (2013, around George Square), Trainspotting (1996 – Edinburgh no longer being suitably seedy), Sunshine on Leith (2013, Merchant City – another one that’s possibly a bit awkward for Edinburgers to admit), Red Road (2006, Red Road Flats), Filth (2013, Pollokshields), Fast & Furious 6 (2013, Cadogan Street), Doomsday (2008, Haghill), Outlander (series 2, Glasgow Cathedral),

THE CONTEXT

The built landscape of Glasgow is a powerful signifier of the city’s modern and contemporary history. It has thrived and survived through different economic eras and the evidence of both boom and bust is still evident today.

Unfortunately, the Victorian regeneration of the city and a general disregard for dilapidated medieval ruins means that little is visible of the city’s heritage previous to the Industrial Revolution. The only two remaining medieval structures are St Mungo’s Cathedral and next-door Provand’s Lordship , in the East End.

However, that still leaves Glasgow with an abundance of architectural heritage that most cities would be envious of: notably Victorian buildings and that era’s contribution of the central grid system, Alexander Thomson’s neoclassicism and the city’s most famous architectural export, Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s ‘Glasgow Style’, an offshoot of the Art Nouveau movement. All will feature heavily on our walk, in which each area tells a different chapter of the Glasgow story.

Glasgow is most known for its mercantile and industrial history and this has shaped the city beyond what is seen at first glance: commercial fortunes financed the city’s galleries and libraries, and the important collections within. However, the decline which began in the Second World War, and sadly outlasted it, was one of the factors in the 1960s regeneration which carved up the city centre and exacerbated the city’s trademark sprawl.

But the city is moving on. The twenty-first century transformation of Glasgow was symbolised by the recent flattening of the iconic Red Road flats, which were set to be immortalised in popular culture one last time, their demolition forming the centrepiece of the Commonwealth Games Opening Ceremony. The plans were cancelled for safety reasons, and not before drawing criticism that this was not the right visual for Glasgow to transmit to the international viewing public. Nevertheless, they came down – finally – in October 2015, bringing to an end one era of urban experiments and ushering in another.

Towards the end of the century, the journalist Ian Jack was able to write in The Sunday Times that “Some marvellous and intriguing things have been happening in the city. Epidemics of stone cleaning and tree planting have transformed its former blackness into chequer works of salmon pink, yellow and green. Old buildings have been burnished and refitted. Museums, delicatessens and wine-bars have opened and thrive. New theatres occupy old churches. Its new appearance persuades that it may become Britain’s first major post-industrial success.”

THE WALK

We begin outside at Gallery of Modern Art, beneath one of the city’s most iconic emblems, the Duke of Wellington statue – which would be pretty unremarkable if not for his hat, which is a traffic cone. It is alleged that repeatedly replacing the cone costs the city council some £10,000 each year!

The Gallery itself was built in 1778 as a private house, using tobacco profits – much of Glasgow’s mercantile wealth was amassed from this industry in particular. It later became a commercial exchange and then the gallery: mercantile wealth has funded many of the city’s cultural assets. The GOMA, as it is known, is also a lovely example of how architecture adapts to citizens’ demands and new purposes at different points in time. Who knows what the building will be in another couple of centuries?

Round the corner in Nelson Mandela Place is the former Glasgow Stock Exchange, the epicentre of the entrepreneurial spirit which has defined so much of the city’s history. It was built in 1875 as a meeting place for businessmen to come together, collaborate and raise capital for their colonial ventures: ground zero for the Second City of the Empire (during the Victorian era, anyway). 98 years later it was merged with the London Stock Exchange, but calls for the reintroduction of a local institution persist, to promote the creation of local businesses and aid regeneration – financial devolution to match the political, perhaps. In any case, Glaswegians aren’t looking to London for anything – they may have been the Second City of the Empire but they are the first city of Scotland and fiercely proud of it.

The gridded area we are navigating through now is called Merchant City, developed from about 1750 onwards with the profits of the so-called “tobacco lords”, who built their homes and warehouses here, kicking off a westwards trajectory of wealth which we will follow for the first half of our walk. Firstly, we head down St Vincent Street, named after a famous victory off the Cape of St Vincent – Britain’s naval success was crucial to those who dwelled and did business in these parts. The Glaswegian tobacco traders were extremely adept at what they did – in fact, their counterparts in London, Liverpool and other British ports complained of their sharp practice to parliament. They were not granted any recourse and the roaring trade continued to bankroll the city and a continued Victorian facelift.

Wide straight streets and large vistas and squares sprang up from the Medieval mire until Glasgow became “the cleanest and beautifullest, and best built city in Britain, London excepted…” (this according to Daniel Defoe, who is the go-to guy on quotes about how salubrious, or not, a city is). The grid system which it was built on was a Georgian invention, which reflected the rationalism of the Scottish Enlightenment and was paralleled by the New Town development in Edinburgh.

Heading through all these straight lines and squares, we eventually end up at the Glasgow School of Art, by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Glasgow’s most famous artist. Together with his art nouveau colleagues, he sought to add some curvature and natural form to all the rigidity which defined the landscape.

Glasgow School of Art

The Glasgow School of Art is Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s architectural masterpiece. His largest, most innovative and most loved project, it is also one of the most influential buildings to be constructed on our British Isles – and my personal favourite on this walk. Like many of his buildings, its design shows influences from the history of Scottish architecture – elements of castles and baronial halls – alongside something completely new. The attention to detail is astounding – look, for example, at the forms of flowers and plants in the metalwork: these represent some of Art Nouveau’s pioneering work. We picked up the Mackintosh trail again a little later in the walk, at the University, but in the meantime a scone from Sauchiehall Street’s Willow Tearooms, which he designed, kept our artistic appetites suppressed…

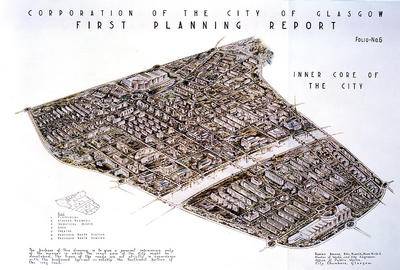

We are all fortunate to be able to visit the School of Art – it was lucky to escape a 2014 fire relatively unscathed and before that it was threatened by a landmark planning proposal, the 1945 Bruce Report. In a classic of the post-war urban planning genre (okay, it’s a bit of a niche), then Glasgow Corporation Engineer Robert Bruce suggested razing much of the city centre (including GSA, Glasgow Central Station, the City Chambers and Kelvingrove Museum) in a sweeping slum clearance.

His plans were vandalistic, radical and short-sighted but no-one would deny their necessity: Glasgow had become one of the most over-crowded cities in the world.

The city’s prosperity had been the pull-factor for wave after wave of immigration, swelling the population by astronomical proportions – leaving hundreds of thousands of new (and old) Glaswegians in a crowded cesspit of chronic illnesses stemming from a lack of light, air and space.

A year on from Bruce, the “Clyde Valley Regional Plan” was published, disagreeing profoundly – instead of complete redesigning large swathes of the city, the newer plan advocated the “New Town” approach, rehousing the slum-dwellers outside the city.

The friction between the two is what shaped Glasgow’s transformation in the second half of the last century – if one or the other had been implemented in its entirety, the city would be unrecognisable from its current state.

However, one part of Bruce’s plan which did go ahead, and which many Glaswegians surely regret, is the running of the M8 motorway through the centre of the city; its screeching lanes tear Charing Cross in two, creating a chasm through the West End. Nevertheless, we cross the sprawling junction, heading for the serenity of a leafier part of town.

The housing stock in the West End is in a very different league to the aforementioned slums; classical villas and attractive terraces of tenements curve around verdant crescents, which back on to the Kelvin. Many of them are the work of the city’s other influential architect, Alexander “Greek” Thomson, who earned the nickname for being an aficionado of the classical (with a great distaste for the gothic, including the nearby University).

The westerly location of all these gorgeous houses was the result of a continuing pull of economic and intellectual influence, stimulated by the relocation of the University to Gilmorehill (it had been in the East End until 1870) and the opening of the Botanic Gardens on the edge of the River Kelvin in 1842.

The Gardens’ centrepiece, Kibble Palace, is the work of Victorian eccentric John Kibble, who designed the enormous structure for his own garden originally (a simple shed obviously didn’t placate his midlife crisis). Luckily for us it was instead brought up the Clyde, piece by piece, and erected in the Gardens for all to enjoy. It resembles an enormous spaceship – the dome alone is 150m in diameter – filled with foliage. The result is a very interesting visual contrast; one not to be missed.

The epicentre of the West End’s bohemian, good times vibe is Ashton Lane: a few hundred metres of cobbles with more eating and drinking establishments than you can shake a stick at. I grabbed lunch at Brel: half a pot of mussels with fries and a coke which left me change from a tenner. Job done.

While I certainly needed a refuel in anticipation of the walk up to the University campus, I did nearly lose my lunch in the Hunterian museum. It’s a really interesting little museum with a very varied collection, but do be aware that a lot of it is medical preparations: grim things like miscarriages still encased in wombs and cancerous skulls, as well as stuffed deformed animals with twice the amount of legs they should have had. Fascinating, I just wish someone had warned me.

From there I go to the Hunterian Art Gallery, fortuitously just in time for a tour of the Mackintosh House – a complete reproduction of 6 Florentine Terrace where the “kunstlerpaar” or “artist-couple” of Charles Rennie and Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh lived (both their work is featured). If you want to get an idea of the Mackintosh aesthetic, this is the best destination.

The whole place is a very definitive move away from Victorian décor – though it doesn’t look that conspicuous to our modern tastes, it would have done when first designed, at the start of the 20th century. This begins right with the very plain hallway, with plain wallpaper, which would have been almost unheard of at the time. Charles’ hallmarks – high-backed chairs, Japanese motifs, white painted wooden furniture all feature very prominently throughout. His departure from the Victorian aesthetic continues with the usage of the space – he intentionally makes rooms smaller by putting a runner round the walls at head height, even blocking windows to do so, in order to shrink the room – he wasn’t a fan of the grandeur of large terrace houses.

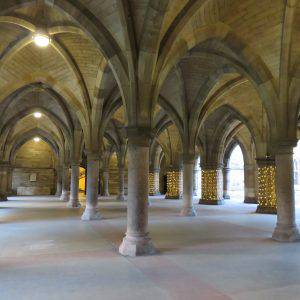

But what of the actual University which houses all this? Glasgow University was first established in 1451 as an adjunct to the Cathedral and expanded onto the High Street a decade or so later, where it remained for four centuries. The current campus’ main building is the second largest example of Gothic Revival architecture in Britain after the Palace of Westminster and, astonishingly, wasn’t a setting for a single one of the Harry Potter films. I would omit that piece of information to any Potter fans you might bring on the walk though, because the splendour of Bute Hall and the bell tower will be enough to convince them otherwise.

magnificent

The campus also offers a fantastic view of Kelvingrove, its turrets poking through the park’s bare trees: classic Glaswegian red sandstone against a typically grey Glaswegian sky. It is really very grand, inside and out, and has a wonderful and varied collection to boot. I only visited the parts concerning Glasgow, but they were brilliant. The standout piece of Salvador Dali’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross which is also well worth a visit.

Kelvingrove from the river

From here, it’s a long old stretch of Argyle Street all the way back to the East End. On the way we pass a landmark little known outside Glasgow, “Heilanman’s Umbrella” – £1 million to anyone who can guess what it is! In fact, it refers to the railway bridge which carries passengers out of Central Station over Argyle Street – it acted as shelter for poor Highlanders arriving in Glasgow in the 19th century.

Eventually we arrive at Glasgow Cross, where Glasgow was centred before the the merchants and bohemians upped sticks. Evidence suggests the Saltmarket was already crowded with buildings in the 13th century, an established mercantile centre centuries before cross-Atlantic trade erupted. To the North, the area around St Mungo’s Cathedral became an ecclesiastical centre. The next section of the walk will take us between these two nuclei.

Firstly, we stroll through Glasgow Green. Granted to the people in Glasgow by James II in 1450, it is the city’s oldest civic park and, for many years, its only green public space. It is easy to forget, now that our public parks are almost exclusively leisure spaces, that they once served many vital purposes. In its early years, the park was used for washing linen, drying fishing nets and grazing livestock.

Plonked in the middle is the wonderful People’s Palace, a museum and glass house intended to provide a cultural centre for the deprived souls of the East End: city engineer Alexander McDonald, in 1898, declared it “open to the people forever and ever”. In addition to a small plant collection in the Winter Gardens (which aren’t really very exciting, when you’ve just come from the Botanics), there is a wonderful social history museum on the first floor. It tells the story of Glaswegians from 1750 to the present day, including the ‘single-end’ (one room tenement), ‘The Steamie’ (laundrette) and dancing at the Barrowland Ballroom. My friend and I were utterly engrossed; it’s the kind of museum where you read every single plaque word-for-word (the best kind).

Onwards and upwards though, towards, in fact, Barrowlands. You may well be wondering why I chose to wend my way through this area – it’s certainly not particularly aesthetically pleasing. Well, you want to get a feel for Glasgow, don’t you? I’m afraid it’s not all Georgian terraced homes and gridded streets – it’s also a bit of scuzz, sectarianism and squalor.

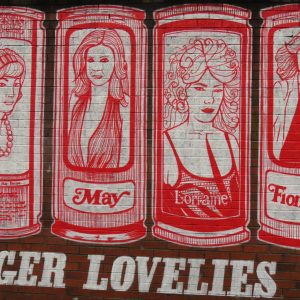

No wonder, then, that Scotland’s most famous brewery is round the corner. Scots’ devotion to Tennents is such that this one brew alone accounts for 60% of the Scottish lager market. On your way up you will walk along the wall emblazoned with all sorts of slogans to do with this wonderful country – sort of like a happier, less ironic counterpart to Ross Sinclair’s neon signs outside the GOMA. Some of the phrases I could particularly identify with, as an English transplant North of the wall: “where umbrellas go to die”, “where ‘corned beef’ is a skin tone” and “strangers one minute, best friends the next”. Go and have a look and find your favourite – it’s all very instagrammable.

Tours round the brewery are available – though I didn’t take one, they receive rave reviews on Tripadvisor. I did stop for a sandwich, however (all this walking you really do work up an appetite!). The Drygate brewery, on the same site, does craft beer and “fearless food for the soul”. I mean, that’s quite the claim, but it did hit the spot.

Up the hill, to the Necropolis. More than ‘just a graveyard’, the Necropolis combines some of the best views of the city with a dark Victorian and Medieval atmosphere. Some 50,000 people have apparently been buried here (though of course they don’t all have a headstone), after the creation of the Père Lachaise in Paris launched a wave of cemetery-building elsewhere.

One of my favourite things about the Necropolis is the view it affords of St Mungos’s Cathedral – one of the best examples of Medieval architecture in Scotland to have survived into the 21st century. It was consecrated in 1197, named after St Kentigern (also known as Mungo), a bishop who allegedly presided over a parish stretching all the way from Cumbria to Loch Lomond. The building itself is absolutely enormous, with an underground crypt which is almost the size of a church, alone.

unfortunately I can’t take credit for this beautiful photo

Just across the precinct is Glasgow’s only other remaining example of Medieval architecture (you can blame the Victorians for not preserving more): Provand’s Lordship. It was built in 1471 as part of a hospital, before falling into use as accommodation for the clergy working nearby. When I visited, it was beautifully preserved, filled with 17th century furniture from the Burrell Collection. Outside is a medicinal herb garden – a very peaceful little corner, particularly the cloisters from which you can look out onto the artfully arranged hedges without getting rained on (always a concern in the West of Scotland).

From here we head down Rottenrow. The name, common in many British towns and cities, signifies a road of ramshackle, rat-infested cottages. Though the street was realigned during the Industrial Revolution, by the mid-20th century the tenements had once again been reduced to slums and the vicinity was named a CDA or ‘Comprehensive Development Area’ in the Bruce Report. Once razed, Rottenrow was actually repurposed as the campus of the new Strathclyde University. On this site also stood the Glasgow Royal Maternity Hospital, which was demolished in 2001 to make way for the final green space of our walk, Rottenrow Gardens. The Gardens incorporate the foundations, basement walls and porticos of the old hospital, while the centrepiece is George Wyllie’s Monument to Maternity: a sculpture in the form of a giant nappy pin.

…or this one

Our walk eventually winds back up in George Square, the de facto heart of the city and the scene of many defining moments in Glasgow’s civic history. It was here in 1993 that Nelson Mandela famously danced to Sowetan pop music and thanked the city for having taken a stand against apartheid. In 2003, between 50,000 and 100,000 people marched from Glasgow Green to the square to protest against the Iraq War (in the end chasing Tony Blair out of town – he had just given a speech to the Labour party conference at the SECC). Perhaps one of the bloodier events was the 1919 Black Friday march for workers’ rights, where strikers clashed with soldiers after Winston Churchill ordered in tanks – remember, this was just 2 years after the Russian Revolution and if a Bolshevist uprising was going to take place anywhere in Britain, then Glasgow was surely as good a candidate as any. Nowadays it is the scene of happier events, such as Hogmanay and the Homeless World Cup.

The silhouette of the Christmas Fair and City Chambers in George Square

The last big political ‘moment’ in George Square was the post-Independence Referendum protests in 2014, which quickly turned into sectarianism-tinged riots after being hijacked by Loyalists. Glasgow had been one of just four constituencies to vote against the tide, and the Square was considered the ‘home’ of the Yes campaign. The result demonstrates the small-’i’ independent streak running through Glasgow: a mercantile and industrial city whose eyes were cast towards the Atlantic, not London, and a cultural powerhouse who takes its inspiration from its own people.

WALK DATA

Distance: 12 kms (7.5 miles)

Height Gain: 200m

Typical time: 3 hours

OS Map: Ordnance Survey Explorer Map 342 Glasgow

Start & Finish: Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art (G1 3AH)

Terrain: flat, bar the Necropolis; often muddy in the parks and along the Kelvin Walkway.

THE ROUTE

- Coming out of Exchange Square, take Buchanan Street northwards before turning left onto St Vincent Street and following it for five blocks. At West Campbell Street, turn up north again for another six, then back onto Bath Street westwards. At Pitt Street, walk northwards two blocks to the Glasgow School of Art, then westwards again on Renfrew Street to Charing Cross.

- Cross the M8 and bear right onto Woodlands Road, then left onto Park Drive, and finally onto the Kelvin Walkway for three quarters of a mile, into the Botanics.

- Come out of the gardens to the south, crossing Great Western Road onto Byres Road, which you will follow down to Hillhead subway station. Turn left onto Ashton Lane and weave through onto University Avenue. Proceed east through the campus until you are once again in Kelvingrove Park, heading along Kelvin Way, parallel to the river.

- Once over the river, near to the Bowling Lawn and Kelvingrove Museum, cross Sauciehall Street onto Argyle Street and turn left. After 650m, you will need to bear right onto Houldsworth Street, before rejoining Argyle Street again.

- Crossing the M8 again at Anderston, you will keep following Argyle Street for a further mile to Glasgow Cross at the Gallowgate. Turn right down Saltmarket, towards the river, and into Glasgow Green through the large stone arch.

- Head through the Green to the People’s Palace, and then round the back, up north again, towards the residential strip between the park and the Barras Market and Barrowlands Ballroom. You will end up back on Gallowgate, this time to the east of Glasgow Cross. Continue northwards on Great Dovehill, then right again onto Bell Street, left onto Hunter Street, which, bearing left, will lead you eventually to the Tennents Brewery, easily identifiable by the smell and colourful beer-themed art.

- Hug the brewery wall round to the left, then head up the hill of John Knox Street towards the Necropolis. After a couple of hundred metres, bear right towards the bridge, crossing into the graveyard before you reach it. Coming back out of the Necropolis, you will cross it towards the cathedral. Head through the cathedral precinct on Church Lane, then turn right onto Rottenrow which will take you through Strathclyde University campus back towards the centre of town.

- At Rottenrow Gardens, cross diagonally onto Montrose Street. Take this street three blocks south, before finally turning right onto Ingram Street, which will lead you back to the Duke of Wellington statue at the Gallery of Modern Art.

PIT STOPS

Willow Tearooms (217 Sauciehall Street, G2 3EX) Traditional tearoom fare served in premises designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Drygate Brewery (84 Drygate, G4 0UT) Craft beer, hearty mains or lighter, build-you-own sandwiches served with lovely sides.

Òran Mór (corner of Byres Road and Great Western Road, G12 8QX) A lovely pub and arts venue, whose centerpiece is the daily lunchtime ‘Play, Pie, Pint’ – which does exactly what it says on the tin, for £10-14 (depending on the day).

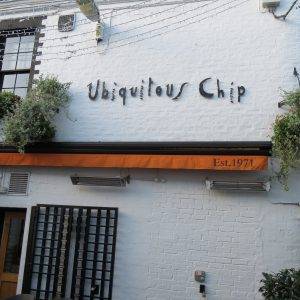

Ashton Lane also plays host to a handful of lovely eateries and pubs at different price points, including Glasgow’s most famous restaurant, Ubiquitous Chip.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Byres Road is full of great vintage shops to be discovered at your leisure – much cheaper than their Edinburgh counterparts.

Monorail, 12 Kings Court, G1 5RB is a music-lover’s paradise, sustaining the city’s music royalty in limited edition vinyls and rare finds.

De Courcy’s Arcade, 5 Cresswell Lane, G12 8AA is home to a handful of small businesses as diverse as a hair salon, tearoom and vintage and gift shops – my favourite find was the handmade Scottish humour cards in Apple Box Gifts. The whole of cobbled Cresswell Lane is good for stumbling across unique bits and bobs.

PLACE TO VISIT

Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art (Royal Exchange Square, Glasgow G1 3AH, Tel. +44 141 287 3050): While not a patch on the National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, GOMA is worth seeing for the neon signs proclaiming “We heart Culloden 1746” and other similarly unexpected slogans – not to mention the infamous Duke of Wellington statue topped with a street cone – Glasgow’s unofficial emblem.

People’s Palace (Glasgow Green, G40 1AT, Tel: 44 141 276 0788): The People’s Palace is a small museum, but a brilliant one. It concentrates on the social history of Glasgow, complete with a replica ‘single-end’; relevant and fascinating for visitors of all ages, too.

Kelvingrove Museum & Art Gallery (Argyle Street, G3 8AG, Tel: +44 141 276 9599): Kelvingrove is enormous and really very grand, inside and out. The collection is extremely varied, so I just visited the parts concerning the history of Glasgow, which were a good complement to what I’d learned in the People’s Palace. In terms of art, the standout piece is Salvador Dali’s Christ of Saint John on the Cross.

0 Comments

2 Pingbacks