Author: Annabel Britton

Dios está en todas partes pero atiende en Buenos Aires.

“God is everywhere but takes special care of Buenos Aires.”

Buenos Aires has ten times less green space per person than New York, and five times less than Paris. However, it also has more bookshops per person than any other city in the world, and its jam-packed calendar of cultural festivals is second only to Edinburgh’s. Its particularly charming kind of grit is impossible to explain – you’ll have to do the ramble to see why I love it so much.

Green Spaces

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | More plazas than you can shake a stick at! Jardin Botánico Carlos Thays, Jardin Japones, Plaza Holanda, El Rosedal, Chacarita cemetery, Recoleta cemetery |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Puerto Madero, Rio del Plata, Lago de Regatas and other small ponds scattered in the gardens, the Tigre Delta (the latter is a daytrip out of BA) |

Fun Stuff

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Florería Atlántico, Parrilla Peña, PROA’s café, Bar El Federal, Café Tortoni |

| Quirky Shopping | Ateneo Grand Splendid, San Telmo’s Markets, |

| Places to visit | Museo de Arte Moderno, PROA, El Conventillo de Matilde |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Festival Internacional de Cine Independiente (Apr), Feria Internacional del Libro (Apr-May), ArteBA (May), La Rural (agricultural fair – late Jul-Aug), Festival de Tango (Aug), Abierto Argentino de Polo (Mid-Nov – Mid-Dec), |

City population: 2,890,151 (2010 census); Buenos Aires conurbation: 12,741,364

Ranking: Biggest in Argentina, 15th largest in the world

Date of origin: 1536, 1580 (the original settlement was abandoned in 1542 owing to indigenous attacks, but later reestablished).

‘Type’ of city: Port City

City walkability (www.walkscore.com): 79 “very walkable”

Some famous inhabitants (porteños): Only the bloody Pope! Lesser humans from BA include Diego Maradona, Jorge Luis Borges (writer), Queen Máxima of the Netherlands, Gaspar Noé (director), Olivia Hussey (actress).

Films/TV shots here: Evita (of course)

THE CONTEXT

Buenos Aires has been though a lot: skirmishes between indigenous inhabitants and newer arrivals, attacks by British, French and Portuguese armies, revolution, communist massacres, a coup d’état – it’s even been fired on by its own navy. Far from neatly passing from colonial Spanish rule to independence, the city has been under a number of dominions: British rule in 1806, for a brief period, then its own seceded state from 1853-60, through to Perón, various juntas and, finally, democracy.

The banks of the Río de la Plata (River Plate) were populated by various indigenous peoples in pre-Columbian times. Alas, their millennia of history are not nearly as important as the 500 years since the arrival of the white man and as such, I was unable to find out much about the city before its foundation by the Spanish.

In fact, the city was founded twice. Firstly, by syphilis-ridden colonist Pedro de Mendoza (I bet he wasn’t the only one), in February 1536. This original settlement, in modern-day San Telmo, had to be abandoned owing to indigenous attacks, which forced the colonists to flee to Asunción (the capital of modern-day Paraguay, up the river Plate). Buenos Aires 2.0 came into being in 1580, when Juan de Garay sailed back down to the estuary and founded the settlement of ‘Santíssima Trinidad’, whose port was ‘Puerto de Santa María de los Buenos Aires’. Thank God they’ve shortened the name a bit since then.

From its inception, Buenos Aires relied on trade: it is a port city through and through. However, for a lot of the 17th and 18th centuries, the threat of piracy meant that Spanish ships were sent to Central America instead, where their cargo would be dispatched across land to Lima and other interior cities. Thus, it still took rather a long time for goods to arrive in Buenos Aires, and the taxes which this system implicated made imports prohibitively expensive.

Needless to say, this situation created a lot of resentment among porteños towards the Spanish viceroyalty, but it wasn’t until the late 18th century that Charles III relaxed the restrictions. In the meantime, an immense trade based on contraband had built up, fuelling the city’s growth – and a French revolutionary mindset had engendered a desire for independence.

It is said that “Argentineans are descended from ships” – and those ships landed in Buenos Aires, carrying not just Spaniards and Italians, but other Europeans and Middle Eastern peoples. While the influence of Catholicism is as strong as you might expect in a country which produced the first Latin American Pope, Buenos Aires has the largest Jewish population in the Americas (New York excepted), and the biggest mosque on the continent.

Such enormous and consistent immigration from the Old World manifests itself plainly in the streetscape.

While almost the entire city is composed according to a grid, they are more manageable chunks than the towering cubes of glass and concrete you might find in São Paulo or New York. A European flavour permeates the city on every level, including its people: Argentinians are said to be “Italians who speak Spanish but think they are British”.

THE WALK

Almost all of the green space which porteños have to enjoy is concentrated in one contiguous collection of parks and paseos in the north east of the city, and this is where we will begin our walk. Our first piece of rus in urbe is the triangular Jardín Botánico Carlos Thays, bounded by Avenues República Arabe Síria, General Las Heras and Sarmiento. It was during the presidency of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento that this neighbourhood, or barrio, Palermo, really took off, following the creation of the Buenos Aires Zoological Gardens, Plaza Italia and Parque Tres de Febrero. Funny what public green spaces can do for a neighbourhood – Palermo remains a very desirable place to live. In particular, Palermo Soho, where I stayed while researching this ramble, is a beautiful place for a wander around and a bite to eat.

But I’m getting ahead of myself – we haven’t worked up an appetite just yet. The botanic gardens were created in 1898 by Frenchman Thays, who had the sheer pleasure of living in the mansion inside the grounds after completion. The lucky inhabitants of the gardens nowadays are the city’s population of abandoned cats – though this has actually become quite the problem for the authorities, since they are left at a rate of one per day during the summer! As I was visiting in autumn, the gardens were perhaps not at their best, but the 33 works of art in the garden are of perennial interest; I particularly liked Ernesto Biondi’s bronze Saturnalia, whose ten figures each depict a different social class of Ancient Rome.

On our way to the Paseo El Rosedal, the next in our long list of gardens, we pass the Monumento a los Españoles, or ‘Monument to the Spanish’, which was actually given by the Spanish to Argentina on the centenary of the Revolución de Mayo, in 1910. At the base, bronze figures represent the four major reasons of Argentina: the Pampas, the Chaco (plains), the Andes and the Plata region. An inscription proclaims freedom for all of Argentina and anyone who chooses to make it their home – after a week in the city, I was ready to take them up on the offer.

The Rosedal possesses no fewer than 18,000 rose bushes, twisting round a pergola along the edge of a small boating lake. Needless to say, it’s a very pleasant place to walk through. The Andalusian patio and Greek bridge, within a space whose very concept is based on Parisian rose gardens, betray the Old World tendencies of Buenos Aires. The city‘s European heritage and history is manifested in almost every way imaginable, from the architecture and green spaces to the atmosphere on the streets and the porteños themselves.

We visited on the 25th May, Independence Day and a public holiday. It was uncharacteristically warm for an Argentine autumn, and the park was buzzing with city-dwellers enjoying the green spaces: truly a sight to warm the urban rambler’s heart.

Our sequence of gardens is followed by a sequence of unusual architectural gems, beginning with the Planetario Galileo Galilei. According to its architect Enrique Jan, the planetarium is one of the few buildings in the world constructed around the concept of the equilateral triangle, and the geometrical theme is continued with the inclusion of the rhombus, hexagon and circle throughout the building.

If the planetarium has at its heart a geometric equality of sides, the MALBA (Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires) goes in the opposite direction, with a late Nineties deconstructivist attitude to shape – polyhedral volumes with acute angles rendered in limestone and glass. The museum is consistently rated very highly on Tripadvisor, with many saying that it would be worth a visit even if there wasn’t any art in it.

Even the benches are intriguing…

The museum was built to house one of the world’s foremost collections of Latin American art, belonging to businessman Eduardo Constantini. He commissioned the museum as a space dedicated to the dissemination of Latin American culture and its promotion at home and abroad. The architects were chosen for the project on the occasion of the Seventh Buenos Aires architecture Bicentennial (1997), and despite the likes of Sir Norman Foster in the competition, the winners were three young Argentines from the Córdoba province. The location of the museum transformed Figueroa Alcorta into a kind of ‘culture corridor’, which the local authorities have dubbed ‘Milla de Los Museos’ or ‘Museum Mile’, linking together no fewer than 15 cultural attractions along this stretch of the avenue.

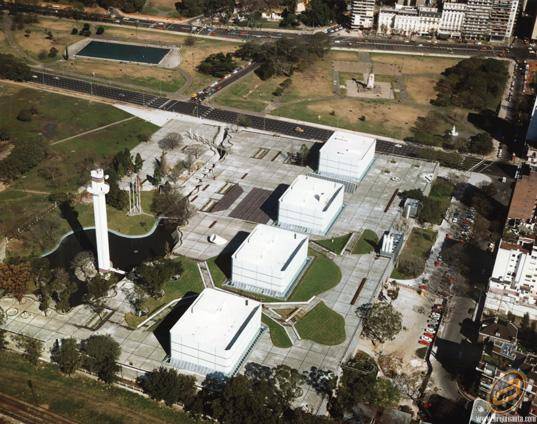

However, our next stop is not in fact a museum, but a TV network. One of the most unusual buildings we’ve ever visited on an urban ramble, the ATC Canal 7 building, by Uruguayan Rafael Viñoly (whose prestigious practice recently worked on the Battersea Power Station master plan). Canal 7 was Argentina’s first television station, established during Juan Perón’s first presidential term, in 1952. The new building was conceived to transmit the 1978 football world cup, hosted in Argentina, in colour for the first time.

It’s almost impossible to do justice to the eccentricity of this building with the written word. It occupies no fewer than three squared hectares, all on one storey. However, it does have different levels – offices at three metres, workshops at nine metres and studios at twelve to fifteen metres. In an effort to provide continuity with the surround ing green spaces, the park almost continues over the top of the building.

Even with an aerial view, it’s almost impossible to get a feel for the building in a two-dimensional image

In sharp contrast to Viñoly’s efforts to blend into the park, the National Library across the road does all it can to stand out. A great brutalist behemoth of books with reading rooms overlooking the trees. I’ll leave it to you to decide which you prefer.

La Biblioteca Nacional

From niche modern architecture, we walk through a couple more plazas to one of the city’s main tourist spots, notably almost entirely because it is host to the grave of (arguably) the most famous Argentine of all: Evita.

The story of Evita is a long one, and since the likes of Andrew Lloyd Webber and Madonna have already rendered it in formats more entertaining than I am likely to achieve here, I am going to skip to the latter chapters. Less than two months after her husband’s re-election, Evita succumbed to advanced cervical cancer. Despite being the first Argentine to receive chemotherapy treatment, she passed away on Saturday 26th July, 1952. Following the interruption of television and radio broadcasts to inform the nation that their ‘Spiritual Leader’ had passed away, bars, cinemas and restaurants were shut, their patrons shown to the door. Within a day of her death, all flower shops in Buenos Aires were out of stock, with additional supplies being flown in from all corners of the grieving nation – even as far away as Chile. Her body was moved from the Casa Rosada to the Ministry of Labour, with thousands sustaining crush injuries as they rushed to see the body as it was transported.

Perón commissioned a memorial to his late wife, projected to be bigger than the Statue of Liberty; Evita’s corpse would be on display at its base, in the tradition of Lenin. However, before its completion, Juan Domingo was overthrown by a military coup, and Evita’s body went missing for some sixteen years. The military were so diametrically opposed to the tenets of Peronism that it was illegal to even mention the couple’s name from 1955-71. In 1971, the military revealed that the corpse had been buried in Milan, under the name María Maggi. The body was then exhumed and maintained in Juan’s home in Spain, with him and his new wife, Isabel, displaying it in the dining room, no less. Evita finally returned to Buenos Aires during Isabel’s presidency (she had been elected vice-president, and assumed the premiership upon Juan’s death in 1974). After a brief display side-by-side with her husband, the body was finally buried in her family’s tomb – no fewer than 24 years after her death. Her final resting place is said to be so secure that even a nuclear attack wouldn’t interrupt her repose.

Owing to the passage of time, the architecture of the cemetery – which contains some 6,400 mausoleums – represents everything from Neoclassical, Neogothic, Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles. For a more complete overview, this pdf guide is highly recommended; tours run in English on Tuesday and Thursday at 11am.

Continuing along from Recoleta to Retiro, we cross the monstrous Avenida 9 de Julio, named to commemorate the Declaration of Independence from Spain in 1816. The widest avenue in the world, 9 de Julio spans, in total, some eighteen lanes – I challenge you to get all the way across in one go! On the face of it, the avenue seems like a grotty piece of urban planning, akin to the chasm of the M8 through Glasgow’s West End; except a giant, American-sized version. In fact, it has won a sustainable transport award for the expedition of its bus rapid transit system through the centre of the avenue, and pedestrian crossings make traversing the avenue surprisingly painless. It helps, of course, that there’s ‘stuff to look at’ along the way, to distract you from the taxis whizzing past your ears at 60mph (Argentine motorists don’t mess around). My favourite sight along the Avenue are the giant murals of Evita, on either side of the Ministry of Social Development, which was unveiled by Peronist president Cristina Kirchner on the 59th anniversary of her death. Handy, because depending on which mural you can see, you know if you are south or north of Belgrano street. Kirchener said, at the unveiling, “I wanted her to look towards the South, towards the factories, towards those bridges which thousands of workers crossed to liberate Perón”. The northern side depicts her speaking into a microphone – or getting stuck into a large burger, depending on who you ask (beauty is in the eye of the beholder, after all).

Shortly after crossing the avenue, we find ourselves at the Plaza de la Embajada de Israel, a poignant memorial to the 29 who died in the 1992 terrorist attack. Since its opening in 2000, 29 lime trees have stood, representing the memories of the victims, which stand steadfast in the history of the city.

Retiro, the neighbourhood we find ourselves in now, is home to many embassies and ambassadors’ residences, among them some of the most ornate buildings in the city. However, it’s also home to two monuments which have come to be somewhat of a physical representation of the biggest diplomatic thorn in Argentina’s side. That’s us, the Brits, in case you were wondering.

At the bottom of the sloping San Martín square, is the Monumento a los Caídos en Las Malvinas’ or the ‘monument to the fallen of the Malvinas Islands’ (what the Argentines call the disputed Falkland Islands). Ironically, just across the road is the ‘Torre de los Ingleses’, or ‘Tower of the English’. Well, in fact, it was renamed ‘Torre Monumental’ following the war, but it is still the focal point of a petty, back-and-forward urban war of symbols, customarily desecrated by anti-English graffiti.

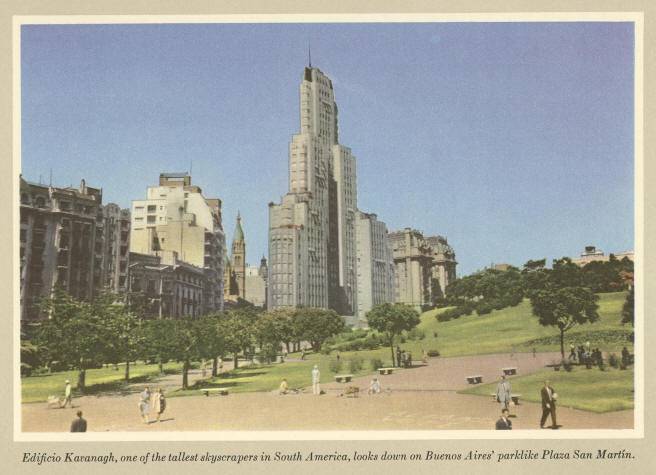

Walking up Florida street, along the side of Plaza San Martín, we come to the biggest monument to pettiness in the entirety of Buenos Aires: Edificio Kavanagh. The story behind it is somewhat of an architectural rehashing of Romeo and Juliet, if you will.

Wealthy, though not aristocratic, Corin Kavanagh, fell in love with a son of the both rich and aristocratic Anchorena family. Perhaps not delighted by the idea of their son dating a woman descended from Irish immigrants, the Anchorenas broke the pair up. The Anchorenas lived in a palace on the edge of San Martín, but had also expended a bit of their wealth in building the extraordinarily ornate Basilica del Santísimo Sacramento (as you do). In retaliation for the Anchorenas’ meddling, Kavanagh promptly sold two ranches to raise some quick cash and engaged architects to build her a skyscraper – the only criteria being that it blocked the Anchorenas view of their lovely new church. That’s one way to get back at the in-laws.

the steeple of the Anchorenas’ basilica is just visible to the left of the Kavanagh

The building ended up being one of the most famous in the city: partially for being the tallest skyscraper in Latin America for years, but also because it is considered the apex of early Modernism in Argentina. It combines this with a rationalist Art Deco style in what is a really unusual and beautiful building – one of many in Buenos Aires, seemingly a hub of weird and wacky architecture.

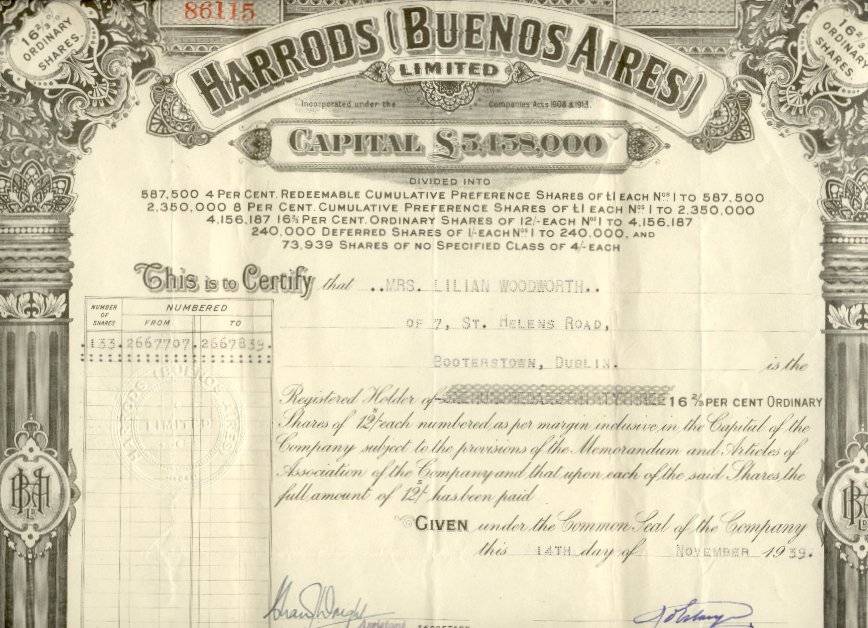

Perhaps one of the more unexpected vestiges of English interests in the city is Harrods Buenos Aires, the only shop ever launched overseas by the quintessential London department store. Opened in 1914, the store occupied an entire city block between Florida street and Avenida Córdoba and was a favourite haunt of the city’s élite, including Evita. It’s death was as slow and painful as that of its First Lady customer: from 1989 its floors closed one-by-one, until a lawsuit brought by Mohammed Al-Fayed put the final nail in the coffin in 1998. Despite rumblings of a reopening around the time of the recovery of the Argentinean economy, a decade or so ago, the Belle Époque building stands largely empty and unappreciated.

The closure of Harrods was the biggest single reason for the decline of Florida Street, which we head down now. BA’s ‘open-air mall’ is bustling now, but was once merely a footpath along a creek which lead to the River Plate. The advent of the Buenos Aires noblery to the area surrounding San Martín transformed Florida into a commercial centre, and a tram was installed along the length of the passage at the turn of the 19th century.

Nowadays, it is possibly the most famous street in the city, full of tourists and street performers plying their trade. However, the most curious inhabitants of Florida are the ‘trees’ – in inverted commas, because they’re not really trees at all. Instead, they are men with fistfuls of green American dollars, like leaves. Now, if I’m being completely honest, I think we should put down the name ‘arbolito’ (little tree) down to a bit of Latin American hyperbole, because these men don’t actually go around waving wads of cash in your face. They’re hardly subtle about their illegal trade though, shouting “cambio, cambio!” at the passers-by. Now, some find this off-putting, but there was a time when this was extremely useful to the tourist, as the best place to get a decent exchange rate for the peso. However, new-ish president Mauricio Macri clamped right down on this when he came to office, meaning that the official rate and the ‘blue market’ rate are now almost identical.

As we veer off Florida towards Plaza de Mayo, we come to the first in a collection of impressive and ornate buildings clustered in the centre of town: the metropolitan cathedral. The cathedral has the impressive claim to fame of being the former seat of Pope Francis, or Papa Francisco, the first South American Pope. Next in the series is the Museo Nacional del Cabildo y la Revolución de Mayo (‘cabildo’ is an antiquated Spanish term for town hall). This beautiful baroque building originally hosted the city’s government, but now is home to a museum telling the story of the May Revolution. It’s truly impressive to think that the building has stood on the same plot since Juan de Garay founded the city in 1580 – the Cabildo has borne witness to the story of Buenos Aires from its foundation.

Plaza de Mayo was bustling when we visited, on the public holiday, and there were even soldiers handing out churros and hot chocolate to the public in celebration.

yum!

This square is the absolute centre of Argentinean public life, and has been ever since the revolution on the 25th May 1810 from which it takes its name – its importance within the city dates back to the time of Juan de Garay.

The square was the scene of the protests which saw Juan Perón freed from prison in 1945, as well as a bombing a decade later, in an effort to overthrow him. In 1982, people gathered to hail the invasion of the Falklands.

34 years later, feelings remain strong: “the Falklands were, are, and will be Argentine”

However, the most famous political occupants of the Plaza are without doubt the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, the mothers of the desaparecidos, or disappeared, who silently protested the murders of their sons and daughters at the hands of the state during the military dictatorship (1976-83). On the 13th April 1977, Azucena Villaflor and thirteen other mothers protested for the first time. Despite the government denouncing them as ‘locas’ (‘madwomen’), the symbolism of silence, and their white headscarves embroidered with the names of their lost loved ones, was more powerful than the junta’s guns and tanks, and has endured to the present day.

Heartbreakingly, Villaflor was kidnapped from her home by armed men and taken on a ‘death flight’, when political prisoners would be drugged, flown out into the Atlantic and hurled out of the plane. In 2005, forensic anthropologists used DNA to identify a body which had washed up south of Buenos Aires in 1977. It was that of Azucena Villaflor. Her ashes were buried in the Plaza de Mayo, where the demonstrations continue each Thursday afternoon, now to support other social causes. 11th August 2016 was the 2,000th Thursday the Mothers have marched, without having missed a single week.

Of course, the primary reason for the politicisation of the Plaza de Mayo is its location right in front of the Casa Rosada, the presidential palace of Argentina. These are the balconies from which Evita addressed the descamisados (‘the shirtless’), and from where her husband later was forced to escape (a scene which was replayed in 2001 when President Fernando de la Rúa also fled in a helicopter from the baying crowds, furious at his inaction over the financial crisis).

The most curious thing about the building is also the most obvious: its colour. There are two principal urban myths explaining the provenance of the rosy hue, and its doubtful we’ll ever find out which one is true (perhaps it’s both!). The political explanation is that President Sarmiento attempted to appease the Unitarists (whose symbolic colour was white) and the Federalists (who wore red) by mixing the two together (perhaps taking his inspiration from Henry VII’s Tudor rose). A more prosaic explanation holds that the pink comes from the inclusion of cow’s blood in the paint, once used to protect structures against humidity. Either way, when you see the way the mansion glows at sunset, you won’t care too much about the reason why.

Walking past that infamous presidential helipad and towards the docks of Puerto Madero, you are now on reclaimed land – the site of the Casa Rosada used to border the Río del Plata. On the ‘city side’ of one of the middle docks, we find the Aduana, or customs house. The enormous scale of the building betrays the huge importance of sea trade and customs to the economy and history of the city, and indeed the entire country.

The massive French Neoclassical edifice was inaugurated in 1910, a golden age in Argentine economic history, when GDP was growing by some 8% each year. From the colonial era until 1930, import revenues accounted for an enormous 80% of the treasury’s revenues, and so this building, in its heyday, was very possibly the most important in the entire country. Its grandeur is certainly fitting, with and hundred-metre-high façade, turrets and marble cladding.

Despite sea trade being the most essential component of the city’s economy since its inception, Buenos Aires always had an issue docking ships, due to the shallowness of the La Boca port. In 1852, the government charged local businessman Eduardo Madero with solving this problem, and he set about constructing the engineering landmark of Puerto Madero.

Unfortunately, just a decade after its opening, it was obsolete, and a long period of decline and degradation set in. During almost the entire 20th century, proposal after proposal was mooted, until in the 1990s, action was finally taken: several government institutions signed a pact to urbanise the area once marked for demolition.

The redevelopment of Puerto Madero from dodgy docks to desirable destination mirrors urban planning programmes from Leith to London. Recently, it has been the star of a massive advertising campaign on the Rio de Janeiro metro, with the clear target market being gringo tourists . Although the project is considered successful, the enormous size of the area – 2.25 million square metres – has made it very expensive, with some locals preferring city funds to be spent on social projects in deprived areas. The marks of large corporate developers and international chain restaurants are writ large: gentrification has priced out many porteños from this district. The price of a square metre of Puerto Madero doubled from $2,500 to $5,000 between 2005 and 2013 – but the agreement states that these profits must be ploughed back into the area, meaning that impoverished districts of Buenos Aires see none of the benefits, though their taxes have contributed to the project.

One inclusive social aspect of the area is the symbolism of the Puente de la Mujer (‘women’s bridge’) and the Parque de las Mujeres, as well as the fact that each street in the area is named after a woman. This, however, remains a symbol – I am sure that less-fortunate porteñas would prefer a gesture that actually improved their lives.

You might argue that the redevelopment of Puerto Madero has transformed an essential urban portrayal of Argentina’s history into the kind of waterside development you could find in any number of the world’s port cities. The same cannot be said of San Telmo: this district is quintessentially porteño.

Disused tram rails on the cobbles, old-school street lamps and the bizarre concoction of architecture make our walk down La Defensa a feast for the urbanist’s eyes. It is the oldest district of Buenos Aires, once its first industrial area, with those who owned the factories and the poor and the slaves who worked in them living more or less side-by-side. When yellow fever struck in 1871, killing 10,000 people, the work of physicians and the church managed to keep it from spreading northwards. This epidemic sealed the fate of Buenos Aires’ demographic and urban history, as the growing middle-class and rich all fled northwards to Barrio Norte. Casting our mind back to the start of the walk, you will remember the gardens of Palermo and the chic embassies of Retiro: this was all built as the monied classes swelled into the northern neighbourhoods.

(A small side-note here: Yellow Fever is spread by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, like the Zika virus. It is interesting to consider what might happen if the latter were to really take foot in cities like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and how that might affect urban rambles to be written years from now.)

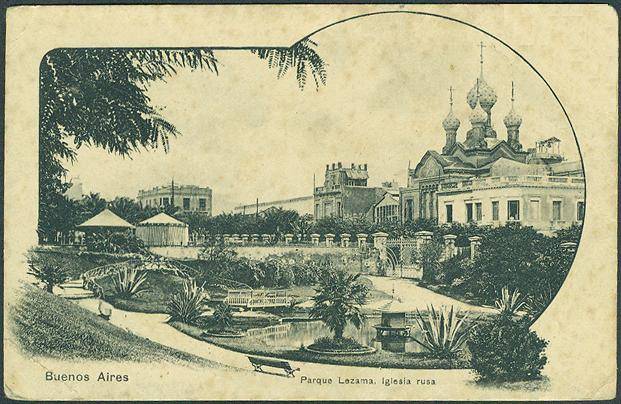

In the meantime, San Telmo’s empty lots were turned into tenement housing for the immigrant workers from Galicia, Britain, Italy and Russia, making it the city’s most multicultural district. The Russian population also created the Iglesia Apostólica Orthodoxa Rusa (just next to Parque Lezama), built at the turn of the last century by Alejandro Christophersen. Incredibly ornate and colourful, it is just another one of several hidden architectural gems which surprise visitors as they make the rounds to the well-known tourist spots.

As the upwardly-mobile immigrant population left to move to swankier neighbourhoods, a less-well-off artist population moved in, bringing with them the bohemian air which prevails today, most obviously noticeable in the markets (one permanent, one each Sunday).

I heartily recommend a visit to the indoor market, at the corner of Defensa and Bolívar (careful – its impressive Tuscan architecture and wrought iron and glass dome can be easily missed!). Its incredibly eccentric mixture of bric-a-brac, largely composed of 70s Argentinean football memorabilia is well worth a look, and the coffee stand inside is very decent – though you may wish to try the local tea, mate (“mah-tay”). There is also a market each Sunday which is incredibly popular with tourists, though it is extremely busy and there isn’t anything particularly unique about it.

The presence of the artist community also gave rise to the museums of modern and contemporary art on Avenida San Juan, housed in a former tobacconist’s with a red brick façade and wrought iron grates (echoed by the intriguing interior architecture).

The bout of yellow fever also freed up space for the Parque Lezama, named after the man whose wife bequeathed the park, in his honour, to the porteño public in the late 19th century. The eastern flank of the park is also the site of the landing of Pedro de Mendoza, Spanish conquistador, when he founded Buenos Aires – for the first time, anyway – in 1536.

It is therefore a very fitting location for the Museu Histórico Nacional, housed in the Lezamas’ mansion on Defensa, which contains articles from all sorts of important people, from General San Martín (instrumental in the emancipation of Spanish South America), Manuel Belgrano (creator of the Argentine flag and another one of its liberators), Bartolomé Mitre (founder of La Nación and former President) and the Peróns (who shouldn’t need an introduction by now).

Our next building is probably the most prized and the most important in Argentine history: La Bombonera, the football stadium to Boca Juniors football club.

Its Swiss blue and gold, an homage to the Genoese who founded the neighbourhood of La Boca – colours not just of the stadium, but every shop, every window, and every sweatshirt to be seen in this part of town. Within the stadium, there is a museum of the history of the club, but that is so very far from being my cup of tea that I moved on towards El Caminito.

As we venture further into the historic neighbourhood, the landscape turns from scene in blue and gold to a veritable rainbow – if you’ve ever received a postcard from Buenos Aires, you’ll recognise the colourful conventillos.

This particular brand of townhouse, embellished in such an original way, has a history behind it which is emblematic of the city. Following the flight of the porteño élite (yes, that pesky Yellow Fever again), the European migrants simply moved into the grand mansions. Owing to their populous nature, they split them up into tenement flats, each housing one family, until the townhouses which had once been a luxurious abode, became the squalid dwelling of some 40 people. Many of them being dockworkers, they would use bits of plywood they had found at the port to mend their homes, while they paint they used to ‘spruce up the place’ had originally been intended to fortify the hulls of the ships coming in and out of BA. Since they never had enough paint to do a whole house, they settled for a multicoloured patchwork of walls, representing the mix of nationalities which lived within them. It truly is a wonderful vision with which to end our ramble.

WALK DATA

Distance: 15.9 kilometres / 10 miles

Typical time: 4 hours

Height change: negligible

Start: Plaza Italia metro station (line D, Avenida Santa Fe)

End: PROA Avenida Don Pedro de Mendoza 1929 (to return to the start, take Magallanes from El Caminito to Avenida Regimento de Patricios, and take the number 39 bus back to Plaza Italia – more info here).

Terrain: BA is an extremely flat city, likely owing to the fact that is on the banks of the Plata (indeed some of it is on reclaimed land). However, the same cannot be said for the pavements, which are an absolute state. Similarly, I can only assume its nickname “Paris of the South” refers in part to a penchant for dogs (and their muck) shared with Parisians… Keep your eyes on the floor!

THE ROUTE:

1. Begin at the Plaza Italia metro station on Avenida Santa Fe. Cross the avenue onto Avenida Sarmiento, with the botanical gardens to your right hand side (there aren’t a great many gates, if you would like to go for a wonder, there is one on Avenida General Las Heras. Follow Sarmiento until the roundabout with Monumento a los Españoles.

2. Here, strike off left through the park, towards Plaza Holanda on the Paseo El Rosedal. Cross the lake at the far end and follow it back towards Sarmiento. Cross back over the avenue, onto Avenida Berro Adolfo. Wander through the rest of the gardens at will, but end up on Avenida Presidente Figueroa Alcorta, heading southeast for one mile.

3. Shortly after passing the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, strike off right down Avenida Pueyrredón for 160m or so, then find your way through the plaza to the Nuestra Señora Del Pilar, at the entrance to the Recoleta cemetery.

4. You will no doubt get lost inside for a good while, but make your way back to the same entrance when you’re ready to continue the walk. Walk back through the same plaza, this time onto Avenida Alvear, which you will follow for one kilometre to Avenida Nueve de Julio. After crossing, follow Alvear which is now called Arroyo. One block after the avenue, the road curves round to the right. Follow along, until you arrive at Juncal street.

5. Go right on Juncal for two blocks before crossing into Plaza San Martín. Wander through to the opposite corner of the park – aim for the grand Plaza Hotel on Florida street. Continue onto the pedestrianised part of Florida street and walk along for 1.2 kilometres. Eventually, you will meet Avenida Presidente Roque Saenz Peña – head left, in a kind of diagonal to Plaza de Mayo.

6. Unfortunately, we have to take a little detour around the Casa Rosada and the presidential helipad. Take Avenida Rivadavia to the left of the Casa Rosada, and cross over the junction with Avenida Leandro Alem. You have probably guessed by now that Buenos Aires’ city planners loved a wide road and a monstrous junction. Follow Teniente General Juán Domingo Perón towards the docks of Puerto Madero. Our walk takes us along the length of this middle dock, directly behind the Casa Rosada – it’s up to you which side to walk down, and if a 10-mile walk isn’t enough exertion, there is a small ‘gym’ on the next bridge down, Azucena Villaflor.

7. Coming off the bridge, walk directly away from the docks on Avenida Belgrano. Two blocks after crossing the large avenue of Paseo Colón, turn left onto Defensa street. Proceed for one kilometre through San Telmo to Avenida San Juan – the red brick museum buildings will be in front of you. Go one block to the left before resuming your southern trajectory on Balcarce for three blocks. The road is parallel to Defensa, passing under the Avenida de la Plata, before hitting the Parque Lezama, next to the Iglesia Ortodoxa Rusa de la Santísima Trinidad. Walk across the park, passing the Museo Histórico Nacional to your left.

8. After crossing Avenida Martín García, continue away from the park on Irala for one kilometre. Toward the end of this stretch, you will see the blue and yellow of the Boca Juniors stadium to your left.

9. When you reach Brandsen street, take a left and then an immediate right onto Práctico Poliza. Follow it down for two blocks onto Olavarría, and repeat the dog-leg manoeuvre – left, then right – to reach Garibaldi.

10. From here, you need only follow the Caminito tourists to reach PROA and the dock.

PIT STOPS

Bar El Federal (San Telmo, close to Plaza de Mayo): El Federal has a very extensive menu, and one which suits almost any time of the day or night. English as I am, I came in around 3pm and had a pisco sour while the porteños were still on their breakfast…

La Floreria (Retiro): A charmingly dark speakeasy beneath a “florists” in Retiro. A great place for a sophisticated aperitif, but if I were you I would move on for dinner somewhere else. Make sure you book!

Café Tortoni (Avenida de Mayo, not far from 9 de julio): BA’s equivalent of Paris’ Café de Flore. Not quite as illustrious, but a Buenos Aires rite of passage nonetheless.

Parrilla Peña: simple and effective steak. My best advice would be to fast in advance and be judicious when you order sides – when they say “steak”, they mean “half a bloody cow”!

QUIRKY SHOPPING

El Ateneo Grand Splendid: Another of the city’s institutions! BA has more bookshops per capita than any other city in the world, and the Grand Splendid is the pinnacle. Housed in an enormous theatre, it really is as grand and splendid as the name suggests.

San Telmo Markets: At Carlos Calvo 430, under an elaborate glass roof, is the Mercado San Telmo – once where locals bought fruit and veg, but now the spiritual home of bric-a-brac (in a good way!). There’s also a lovely coffee stand inside if you need a pick-me-up. On Sundays, Defensa street plays host to a long market – although, it is uniquely a tourist’s pursuit. Worth a look if you’re passing through, but you needn’t look at every single stand as they seem to repeat themselves every few hundred yards…

MUSEUMS ETC.

PROA (La Boca, close to Caminito): A lovely little gallery whose greatest work of art – in my opinion, anyway – is the building which houses it: a concrete and glass dream with a view over the port. That, and the café!

Museo de Arte Moderno: A good little cultural stop-off between San Telmo and Puerto Madero, though be warned, it is very “modern art” (by which I mean one of the works when I was there included potatoes. Potatoes for goodness’ sake!).Conveniently, the Museum of Contemporary Art is right next door, too.

0 Comments

2 Pingbacks