In devising great routes for urban rambles, I have tried to maximise the amount of the route through green spaces, as these typically provide the greatest pleasure, walkability and interest.

In this chapter I look at all the different type of urban green spaces and consider three things:

- Their origin

- Their development

- Their walkability today

Categories:

A. ‘Tended’ Green spaces – for pleasure

B. ‘Tended’ Green spaces – for use

C. ‘Un-tended’ green spaces

|

D. Water features

E. ‘Natural’ green spaces

F. ‘Controlled’ green spaces

|

A. TENDED GREEN SPACES – DESIGNED FOR PLEASURE

Introduction

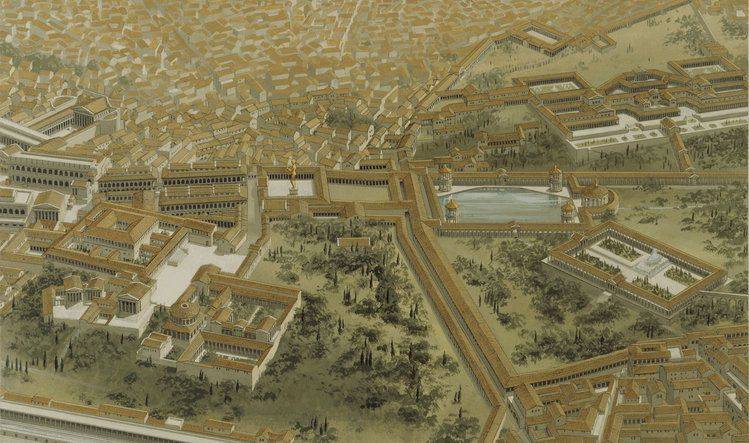

The Romans were the first civilization to recognise the benefits of rural features within a city; from the Campus Martius that was transformed into plush parkland by Augustus, incorporating lakes and space for recreation & leisure; to the ‘horti’ (urban villas within a park) created by wealthy Romans; reaching its zenith in Nero’s ‘Domus Aurea’, which embraced nature on an altogether grander scale and literally brought the countryside to Rome. Nero’s palatial grounds incorporated the cultivated environment and untamed wild simultaneously, housing a multitude of wild and domestic animals, vineyards and tilled lands, offset by the rural seclusion of woods and open ground.

The desirability of nature in Rome was seen as twofold: as a mark of civilization and as a promoter of health & well-being. They coined the phrase ‘rus in urbe’ to describe it.

‘Rus in Urbe’ – the country in the city – has been used in Britain ever since to refer to country features created in towns or cities. A thousand newspaper articles today use it as shorthand to describe a desirable new green feature that is proposed or that needs protection in a city. It has become the ‘go to’ phrase of the green space cognoscenti.

- Squares

Todd Longstaffe-Gowan’s ‘London Squares’ is an exquisite exposition of the contribution that squares have made to our capital city. In it he writes:

“Modern-day London abounds with a multitude of gardens, enclosed by railings and surrounded by houses, which attest to the English love of nature. These green enclaves are among the most distinctive and admired features of the metropolis and are England’s greatest contribution to the development of European town planning and urban form. They epitomise the classical notion of ‘rus in urbe’, the integration of nature within the urban plan – a concept that continues to shape cities to this day.”

The benefits of green space in British towns were recognised as early as the 17th century. In 1618 a Commission on Buildings was established to oversee the development of Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London. The aim of the commission was to ensure that the fields were set out with ‘faire and goodlye walks, which would be a matter of great ornament to the Citie, pleasure and freshness for the health and recreation of the Inhabitants thereabout, and for the sight and delight of Embassadors and Strangers coming to our Court and Cittie, and a memorable worke of our tyme for all posteritie.”

Open areas between terraces were created around the aristocratic developments to the west as part of a Royal mandate to create open space to preserve or modestly enhance the rural character of the setting. James I created a special commission on the matter, which in 1615 affirmed his policy of transforming London into a “truly magnificent city comparable to the Rome of the Emperor Augustus”. The open spaces created typically started life as unelaborated spaces in the centre of the city’s seventeenth century-piazzas.

But by the 1720s many of these spaces in residential areas had become choked with rubbish and the focus of crime and anti-social behaviour. Most were poorly maintained and open to abuse by both the public and the square’s own residents. A debate was engaged on what could be done.

Fairchild, who ran a nursery off Hoxton Square, wrote in the City Gardener (1722) about how to lay out London squares in the ‘Rural Manner’: “I think some sort of wilderness-work will do much better, and divert the Gentry better than looking out of their Windows on an open Figure. St James’s Park is as much oppressed with the London smoke, as almost any of our great Squares; yet the wild Fowl, such as Ducks and Geese, are conformable to it, and breed there; and there is an agreeable Beauty in the Whole, which is wanting in many Country Places.”

In 1726 the St James’s Square Enclosure Act was passed, which created a board of trustees with the power to make a regular charge on residents in order to ‘clean, repair, adorn and beautify’ the square. This was a turning point, and many other squares followed suit with their own Acts. This urge to enclose was, in the words of one contemporary commentator, to protect the spaces from the ‘rudeness of the people’.

By the early nineteenth century, Hermann von Puckler-Muskau was reflecting on the image of the square we have become accustomed to in costume dramas: “Country and town in the same spot is a charming idea. Fancy yourself in an extensive quadrangular area surrounded by the finest houses, and in the midst of it beautiful plantations, with walks, shrubberies, and parterres of fragrant flowers, inclosed with an elegant iron railing, where ladies arranged on all the splendour of fashion are taking the air. Thus the inhabitant of the square has a rural prospect before his eye, without having to leave the square.”

By the start of the 20th century there were over 200 town squares in the capital, but most of them were enclosed and only accessible to the local residents who held a key. So for most people they were something to observe rather than enjoy at first-hand.

Virginia Woolf reflects on the allure of the square in her 1930 ‘Street Haunting: A London Adventure’: “How beautiful a London street is then, with its islands of light, and its long gloves of darkness, and on one side of it perhaps some tree-sprinkled, grass-grown space where night is folding herself to sleep naturally and, as one passes the iron railing, one hears those little cracklings and stirrings of leaf and twig which seem to suppose the silence of fields all round them, an owl hooting, and far away the rattle of a train in the valley. But this is London, we are reminded; high among the bare trees are hung oblong frames of reddish yellow light – windows; there are points of brilliance burning steadily like low stars – lamps; this empty ground, which holds the country in it and its peace, is only a London square, set about by offices and houses.”

During this period, awareness of the importance of squares to the overall fabric of the city grew, and in 1931 the London Squares Preservation Act was passed, limiting the use of London Squares to ‘ornamental pleasure grounds or grounds for play, rest and recreation’, and the only buildings and structures allowed are those which are ‘necessary or convenient for, and in connection with, the use and maintenance of such squares.’

Paradoxically it was the Second World War that opened up many squares to the general public. As part of the war effort almost every square was stripped of its metal railings which were melted down as scrap iron. Several squares also became part of the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign and were turned into temporary allotments. George Orwell saw the removal of railings as a ‘democratic gesture’ that had the potential to improve London ‘out of recognition’.

This opened up the possibility after the war of the democratisation of these spaces, which coincided with the great social progress of the period 1945-1950, and the formation of National Parks, designed to be within reach of the main centres of population.

But of most significance to urban planning was ‘The Abercrombie Plan’ in 1943, which was designed to bring ‘ a new order and dignity to the whole of the County of London’ in view of the rapid changes that had taken place in the previous decades and the effect of bomb damage and major population shifts.

Abercrombie held an enlightened view of squares, believing that in future they should ‘be open to full public use’. For him, the loss of the squares’ railings, although regrettable, had ‘brought them into the life of the community and destroyed their isolation’. He furthermore suggested that the honoured ‘tradition of the domestic square could be developed in the areas of reconstruction’, as the squares could provide ‘communal gardens for adults with play centres for children’. As for the squares that were to be found in the central business areas, these, he believed, should take the form of rest gardens for lunch-hour use. Very much a vision for the way that squares have developed into the 21st century.

Whilst this discussion has very much focused on the London garden square, which constituted the vast bulk of The UK’s garden squares, it is representative of the general trends in squares across the country.

It is very hard to tell from a map in advance if a square has public access or not; if you zoom in sharply enough on Google street view you can generally see if there is an open/unlocked gate or not; and all our walks take you through squares where possible, and this is clearly marked.

Further study:

- The London Square, Todd Longstaffe-Gowan, Yale 2012

- Open Space and Park System chapter from the Abercrombie and Forshaw County of London Plan 1943-4, online

- Parks

There are two main strands to the history of parks that we need to look at: the ‘Royal Park’, which began life in the thirteenth century as a hunting ground; and the ‘Municipal Park’, which started life in the 19th century as a ‘green lung’ in rapidly expanding cities.

2.1 The Royal Parks

London’s Royal Parks are lands originally owned for the recreation (mostly hunting) of the royal family. They are part of the hereditary possessions of The Crown.

Starting in 1845 with Regent’s Park, they were opened to the public on a grace and favour basis. The public does not have a legal right to use the Parks, although there are some public rights of way across the land. The Royal Parks Agency manages the Royal Parks under powers derived from the Crown Lands Act 1851. As part of its statutory management function the Agency permits the public to use the Parks for recreational purposes, subject to the Royal Parks and Other Open Spaces Regulations (1997).

There are eight parks formally described by this name and they cover almost 2,000 hectares (4,900 acres) of land in Greater London: Bushy Park, Green Park, Greenwich Park, Hyde Park, Kensington Gardens, Regent’s Park, Richmond Park and St James’s Park.

Walkability through all the Royal Parks is generally excellent and it quite often feels as if you are deep in the countryside (I even found myself walking through a ‘bog’ in Richmond Park). They are one of London’s very greatest assets.

Further study:

-

London’s Royal Parks, Paul Rabbitts, Shire Library 2014

- You can find out more about Royal Parks at www.royalparks.org.uk

2.2 The Municipal Park

The industrial revolution led to the rapid growth of cities and the emergence of a whole string of northern cities that were literally created during the nineteenth century. Inevitably the infrastructure of these cities struggled to keep up with this rapid growth, and the result was poor sanitation, extreme poverty, slum housing and extensive air and water pollution.

Whilst for many Victorian entrepreneurs this was of secondary consequence, there were also philanthropists and politicians who wanted to improve the lot of the city dweller, through better sanitation and the provision of open spaces. In 1833 The Report of the Select Commission on Public Walks was published, advocating the provision of public parks in cities as an important factor in improving urban living standards. It noted:

“With a rapidly increasing population, lodged, for the most part in narrow courts and confined streets, the means of occasional exercise and recreation in the fresh air are everyday lessened, as enclosures take place and buildings spread themselves on every side. A few towns have been fortunate in this respect from having some open space in their immediate vicinity…yet even at these places…the accommodation is inadequate to the wants of the increasing number of people.”

After seven years of campaigning, Manchester set up the Committee for Public Walks, Gardens & Playgrounds in 1840; and in 1846 three parks were opened – Queen’s Park and Philips Park in Manchester, and Peel Park in Salford – the genesis of the municipal park revolution.

Meanwhile they had been pipped to the post by Derby Arboretum, opened in 1840 and generally accepted as Britain’s first public park. It was the inspiration of a wealthy local textile manufacturer and philanthropist, Joseph Strutt. In his words: “As the sun has shone brightly on me through life, it would be ungrateful in me not to employ a portion of the fortune which I possess to offer the inhabitants of the town the opportunity of enjoying, with their families, exercise, and recreation in the fresh air, in public walks and grounds devoted to that purpose”. It was one of a number of parks visited by Frederick Law Olmsted while on a research tour of Europe in 1859, as input into his design for Central Park in New York.

During the early decades, the park movement tended to concentrate on large prestige projects located on the outskirts of towns. Gradually it was recognised that these parks were inaccessible to the majority of urban dwellers who did not happen to live close to them and that there was a need for small, more accessible inner-city parks and gardens. The movement to create small parks and recreation grounds in inner-city areas dates from the 1880s.

By the outbreak of the First World War, there were around 27,000 urban public parks in the UK, and they were highly valued by the population. In both wars, but much more extensively in the Second Wold War, parks were used as a vital resource, often combining many roles – an area for cultivation, air raid shelters, anti-aircraft guns (many parks tend to be on a hill or a contour) and military installations.

But inevitably this left many parks in a dilapidated state at the end of the war, with post-war re-building efforts inevitably focussed on housing; and the situation became worse in the 60s and 70s as park funding was cut back.

This led to the closure of facilities such as cafés and toilets, a reduction in policing and management (much of which used to be carried out by park keepers) and the creation of banal, low-maintenance landscapes.

It was really not until the mid 1990s that campaigning groups (notably The Open Spaces Society, the Garden History Society and the Victorian Society) really started to change attitudes; and Urban Regeneration Policies increasingly recognised the importance of ‘green spaces’ in promoting fitness and well-being. But the real game changer was The Heritage Lottery Fund, which has invested a game-changing £700 million in public parks over the last two decades, and continues to be a huge advocate of them. So many of the parks that we have walked through have been renovated and improved as a result of lottery funds, usually with matched funds from councils and other bodies. This has truly enhanced the urban landscape and has been at the heart of a better city walking experience over the last generation. Find out more about what they get up to at: https://www.hlf.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/public-parks-under-threat

The tide of opinion has turned back in favour of public parks from all quarters and they are seens as being at the heart of progressive urban policies:

Commentators: A typical eulogy comes from Peter Harnik in his book ‘Urban Green’: “For city residents the world over, public parks hold a special place in our hearts. They’re our backyards, our country escapes, our athletic facilities, our beaches, and our nature preserves all rolled into one. They are places where families from every imaginable background come together and share in the sense of community that is at the heart of city life. Parks help clean the air we breathe, reduce carbon emissions, attract business and tourists, and provide a home for cultural celebrations and events. And for city kids, parks are living classrooms where the natural world comes alive.”

Politicians: Landscape Design Magazine surveyed politicians and others on their views of urban parks. An overwhelming majority saw parks as ‘green lungs . . . green havens . . . breathing spaces . . . refuges . . . sanctuaries.’ A Parliamentary Select Committee formed in 1999, chaired by Andrew Bennett MP, led to the setting up of a taskforce on town and country parks. Research showed that the British public value parks and open spaces and that good quality parks are ‘essential to the well-being and future’ of towns and cities.

The People: This Bow Neighbourhood Signboard sums it up beautifully: “This Park belongs to the people of East London, if you harm it, you harm them.”

The huge challenge now remains adequate funding, particularly in an era of renewed council cutbacks where the ‘must haves’ (healthcare, rubbish collection etc.) are inevitably prioritised over the ‘nice to haves’.

Further study:

- The Park and The Town, George Chadwick, Praeger 1966

- London’s Parks & Gardens, Jill Billington, Frances Lincoln 2003

- Public Parks, Hazel Conway, Shire Garden History 1996

- Urban Green: Innovative Parks for Resurgent Cities, Peter Harnik, Island Press 2010

- Places of Amusement and Health, Liverpool’s Historic Parks and Gardens, Katy Layton-Jones and Robert Lee, English Heritage, 2008

- National Review of Research Priorities for urban parks, designed landscapes and Open Spaces, Katy Lyon-Jones, 2014, English Heritage Online

- Re-thinking Parks, Peter Neal, 2013, Heritage Lottery Fund online

- Green Spaces, Better Places, final report of the Urban Spaces Taskforce, 2002, DTLR online

- www.loveparks.org

- State of UK Public Parks, Heritage Lottery Fund, 2014, online

2.3 Campuses

Campuses are an intriguing sub-set of parks, designed to create peace and harmony around a seat of learning. The word originates with Augustus’s Campus (field) and was first used to describe the grounds of New Jersey College (now Princeton University) during the 18th century.

In the 20th century it was adopted by the new post-war British universities, and in many ways was a more contemporary, open and inclusive version of the ‘closed’ collegiate court. Nature is implicitly felt to be a good environment for contemplative, untrammelled thinking.

The Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography reflects: “Green spaces are an integral part of many university campuses. Universities with attractive green space areas often highlight these as attributes which contribute positively to the student experience and the image of the university. Students both use and appreciate green spaces, and consider them important for the image of the university and as an essential component of the campus environment.”

- Botanical Gardens

The first Botanic Garden was founded in Oxford in 1621 with the mission “to promote the furtherance of learning and to glorify nature”. Edinburgh followed in 1670, the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1673, Glasgow in 1705, Kew in 1753 and Cambridge in 1760 (on another site from today’s). The high point for Botanic Gardens was the first half of the nineteenth century, when seventeen were founded.

Whilst the early gardens were most linked to institutions and designed to provide living material for the study of botany, the Victorian gardens were usually privately funded – and, in addition to the botanical collections they also included ornamental features designed for recreational use and pleasure.

The second half of the 20th century saw increasingly sophisticated educational, visitor service and interpretation services. Botanical gardens started to cater for many interests and their displays reflected this, often including botanical exhibits on themes of the environment and sustainability.

With decreasing financial support from governments, revenue-raising public entertainment increased, including music, art exhibitions, special botanical exhibitions, theatre and film, this being supplemented by the advent of ‘Friends’ organisations and the use of volunteer guides.

Because they are usually walled and gated, botanical gardens often get overlooked by visitors to a city, but they are always worth hunting out, albeit they will add a little to the cost of your day; on the plus side you can you usually enter by one entrance and exit by another and the cafés are usually delightful places to dwell.

Further study:

- Botanic Gardens: A Living History (Gardens), by Brian Johnson et al, black dog publishing, 2007

- An Oasis of Delight, The History of the Birmingham Botanical Gardens, Phillida Ballard, Duckworth 1983

- The Sheffield Botanical Gardens: A Short History, Jan Carder, 1986

- Gardens/flowerbeds/verges/tree-lined streets

Front gardens, street planters, centres of roundabouts, underpass planters, verges – all the little bits of green that make a city more human and pleasant to pass through.

A famous campaign began in New York in the 70s under the banner of Green Guerrillas. They describe its inception on their website: “In the early 1970s, Liz Christy and the original band of green guerrillas decided to do something about the urban decay they saw all around them. They threw “seed green-aids” over the fences of vacant lots. They planted sun flower seeds in the center meridians of busy New York City streets. They put flower boxes on the window ledges of abandoned buildings.”

Soon they turned their attention to a large, debris-filled vacant lot on the corner of Bowery and Houston Streets. Where other people saw a vacant lot, they saw a community garden. People donated their time and talents. Local stores and nurseries donated vegetables clippings and seeds. They created the Bowery Houston Farm and Garden – and they sparked a movement.

In a recent book, the ‘Rurbanite’, Alex Mitchell paints a picture of this movement coming to Britain. “A growing number of us have had enough of neglected flowerbeds, bare street planters and soulless roundabouts. So we’re taking matters into our own hands, planting bulbs ad sowing seed bombs.” The UK version of the Urban Guerrillas can be found at http://www.guerrillagardening.org/ Lots of good stuff in there.

In the words of acclaimed urban guerrilla Richard Reynolds: “Let’s fight the filth with forks and flowers.”

Further study:

- The Rurbanite, Alex Mitchell, Kyle Books. I love Alex’s definition of a rurbanite n. someone with a passion for the countryside but a reluctance to leave the city any time soon.

Tree-lined streets

Where climate and circumstances permit, almost all communities in the world plant and preserve trees in the centre of their towns and cities. The earliest written evidence of a tradition of legally protecting urban trees is found in Hammurabi’s Code of Laws, an ancient Babylonian text, which details the imposing of a fine of half a mina for removing a tree without the owner’s permission.

In ancient China successive dynasties routinely destroyed the previous dynasty’s literary and cultural works with the notable exception of texts on agriculture and arboriculture. Across cultures and historical periods, there is evidence of urban trees being valued for both economic and aesthetic reasons.

However, illustrations of Britain’s town centres from the 18th-century show that street trees were not common at that time. They were predominantly planted in garden squares and in the formal gardens of large houses.

Georgian squares, which were originally treeless, came to be shaped by the new English picturesque style. An early example of this type of development was Russell Square in London designed by Humphry Repton at the beginning of the 19th century. Formal street tree planting started in London in the mid 1850s with a housing development along Margaretta Terrace in Chelsea and thereafter the new vogue for planting street trees began to spread across London and then to other British cities.

Street tree planting really came of age during the inter- and post-war periods when large residential suburban estates around London were developed in response to the extension of the Northern, Piccadilly, Central and Metropolitan Lines. Similar suburban development took place south of the Thames and popular street names like Acacia Avenue, Hawthorn Road, Cherry Tree Avenue and Lime Grove became synonymous with suburban development all over the country.

There are now an estimated 8 million trees in Greater London, more than in any other city in the world: a quarter of these trees are in woodlands; woodlands occupy 8% of London’s land area; an estimated 20% of London’s land area is under the canopy of individual trees. Sadiq Khan promises to plant a further 2m trees in London if elected mayor in 2016. The pattern is the same in other cities: Birmingham is estimated to have 6 million trees and Sheffield 2 million.

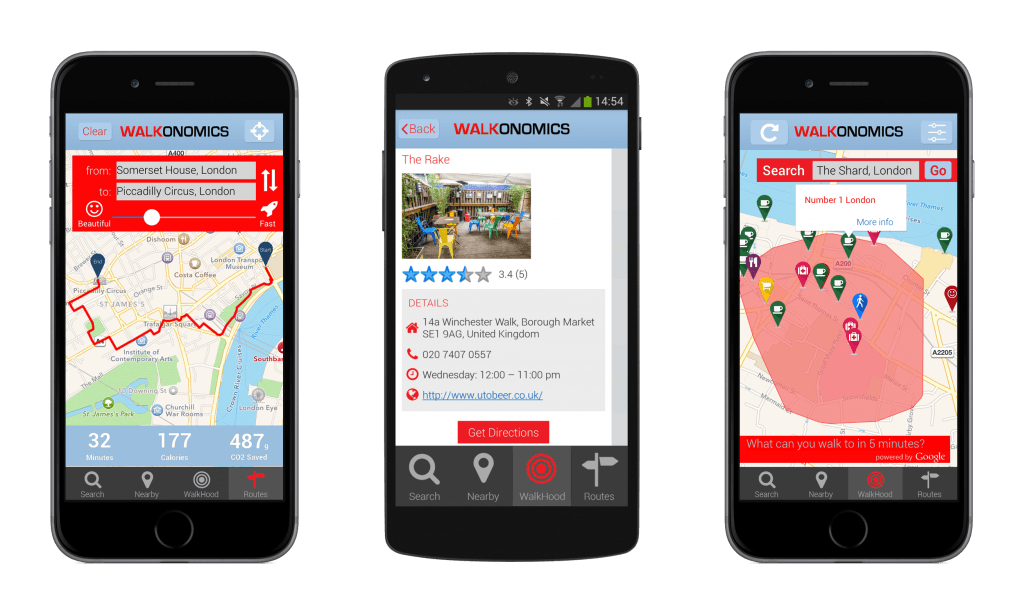

There’s even an app now, Walkonomics, which will take you along the most tree-lined route possible as you walk from one point to another.

Further study:

- Trees in Towns and Cities, Mark Johnston, Oxbow Books 2015

- Connecting Londoners with Trees and Woodlands, Forestry Commission 2005, online

B. TENDED GREEN SPACES – FOR USE

Introduction

A huge amount of green spaces in cities is designed for a specific function– and what they might lack in accessibility they more than compensate for in the sense of creating a ‘a living city’ – places to grow things, take exercise and commemorate loved ones – they are a central part of everyday life.

- Allotments

Allotments are small parcels of land rented to individuals usually for the purpose of growing food crops. There is no set standard size but the most common plot is 10 rods, an old measurement equivalent to 302 square yards. This is judged to be of sufficient size to meet the needs of a family.

The land itself is often owned by local government (parish or town councils) or self-managed and owned by the allotment holders through an association. Some allotments are owned by the Church of England.

Allotments have been in existence for hundreds of years, with evidence pointing back to Anglo-Saxon times. But the system we recognise today has its roots in the 19th century, when land was given over to the labouring poor for the provision of food growing as compensation for loss of commoners’ rights during the onset of enclosure. The General Enclosure Act of 1845 and later amendments attempted to provide better protection for the interests of small proprietors and the public.

In 1908 the Small Holdings and Allotments Act came into force, placing a duty on local authorities to provide sufficient allotments, according to demand. However it wasn’t until the end of the First World War that land was made available to all, primarily as a way of assisting returning service men (Land Settlement Facilities Act 1919) instead of just the labouring poor. The rights of allotment holders were strengthened through the Allotments Acts of 1922, but the most important change can be found in the Allotments Act of 1925 which established statutory allotments which local authorities could not sell off or convert without ministerial consent. Further legislation has been listed over the intervening years which have protected allotments, the latest of which is the Localism Act 2012.

The biggest spur to allotments in the twentieth century was undoubtedly wartime food shortages; their use to support the war effort was enshrined in the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) in the First World War and the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign’ in the second, which encouraged full use of existing allotments and created many new ones, including temporary ones on playing fields and in parks.

If squares are one side of a coin – the elitism of enclosure – then allotments are the reverse side of the coin – the spaces created for displaced commoners.

The big problem with allotments from a walker’s point of view, however, is that allotment owners generally dislike people walking through their allotments – through a fear, real or imagined, that their favourite tools will get plundered or their prize crop ransacked the night before a competition. Many a time I have been stared at or asked to leave from a path running through an allotment; and signs on the edge generally state that only allotment owners may enter. But there are plenty of paths alongside allotments to savour, and I will show you a few of these in our walks.

Today of course allotments are very ‘fashionable’ with the shift to organic produce and sustainability, and the arrival of the ‘celebrity’ chefs who are happy to film in the scenic surrounds of an allotment. BBC2 has even made a programme about allotments; ‘Grow, Make, Eat: The Great Allotment Challenge’. A quick search of Amazon reveals 20+ books in print on How to Manage your Allotment, even two allotment jigsaw puzzles – a sure sign that it has become a truly middle-class obsession!! There is estimated to be 330,000 plots in the UK, with current demand for a further 90,000 plots. The National Allotment Society (www.nsalg.org.uk) campaigns for the development and protection of allotments. In their report, they list the benefits of allotments:

- providing a sustainable food supply

- giving a healthy activity for people of all ages

- fostering community development and cohesiveness

- acting as an educational resource

- providing access to nature and wildlife, and acting as a resource for biodiversity

- giving open spaces for local communities

- reducing carbon emissions through avoiding the long-distance transport of food.

A powerful set of reasons to get down there!

I like the description of allotments in the book ‘Edgelands’: “Trains afford us the best views of allotments, a secret landscape often invisible from our main roads. Allotments signal that you are now passing through edgelands as emphatically as a sewage works or a power station. They thrive on the fringes, the in-between spaces.” (p. 106)

Recently, the idea of self-sufficiency has bred a new generation of thinkers who support the concept of urban farming. This is enthusiastically covered in Jojo Tulloh’s book ‘The Modern Peasant: Adventures in City Food’. Her aim is to reveal a city teeming with small-scale food producers bringing ancient rural skills to the urban environment. So, in London, we get artisan bakeries under Hackney railway arches, Rastafarian beekeepers in Wanstead and soya producers trading just off Brick Lane. “In the city there are now independent beekeepers, vegetable gardeners and sausage-makers. These things used to come from the country – but now they’ve moved to the city,” she says.

Further study:

- Growing Space: A History of the Allotment Movement, Lesley Acton, Five Leaves Publications 2015

- The Allotment Chronicles, Steve Poole, The Nostalgia Collection 2006

- The Modern Peasant: Adventures in City Food, Jojo Tulloh, Chatto & Windus 2014

- Playing Fields, Greens and Playgrounds

6.1 Playing Fields

The Fields in Trust charity, (Formerly the National Playing Fields Association) (www.fieldsintrust.org) sees its mission as: “From sports pitches to children’s playgrounds, bicycle trails to country parks we make sure that all kinds of outdoor spaces are safeguarded forever.

“Formed in 1925 as the National Playing Fields Association we aim to ensure that everyone has access to free, local facilities for healthy outdoor activities.”

“Outdoor spaces have a vital role to play in creating healthy communities helping not only to increase physical activity but also to foster social cohesion and improve the local environment.

“Our work is as vital and relevant now as it was back in 1925 with outdoor spaces continuing to come under threat from development every single week.”

The charity encourages local authorities to adopt a minimum standard of provision of 6 acres (24,000 m2) of public open space for every 1,000 people, of which at least 4 acres (16,000 m2) should be set aside for team games, tennis, bowls and children’s playgrounds. They currently protect over 2,200 public recreational spaces through legally binding agreements for the long term. Their latest report can be found at http://www.fieldsintrust.org/Upload/file/Survey%20findings.pdf

(show poster National Playing fields Association)

I have seen the pressure on sports fields at first hand in my local town Stamford. Our local playing field is a green lung in the residential part of town and was recently the subject of an attempted property development. It was fiercely fought against and the campaign was led by local GPs who highlighted the vital health benefits of the space. It is alive and kicking still as a sports ground!

Access across playing fields, unlike allotments, tends to be reasonably good when games are not taking place. They are very popular dog walking routes too.

6.2 Playing Greens

In terms of acreage, this is predominantly golf courses, which tend to be very restrictive in terms of where you can walk. And even when you are on a public footpath walking across a golf course you often feel that many disapproving eyes are beaming down upon you; and they are well armed with clubs and ammo, so resistance would be futile.

Golf course are specifically excluded from The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (CROW), which introduced a public right of access on foot on areas of open country and registered common land.

So, not a lot of walking opportunities, although several have public footpaths running along their edge, which often have rich woodland and verge habitats.

6.3 Playgrounds

The idea of the playground originated in Germany and was invented as a platform for teaching children correct ways to play. The first UK purpose-built children’s playground was built in 1859 in a park in Manchester.

Although they had appeared before this period, playgrounds were properly introduced to the United States by President Roosevelt in 1907, of which he said:

“City streets are unsatisfactory playgrounds for children because of the danger, because most good games are against the law, because they are too hot in summer, and because in crowded sections of the city they are apt to be schools of crime. Neither do small back yards nor ornamental grass plots meet the needs of any but the very small children. Older children who would play vigorous games must have places especially set aside for them; and, since play is a fundamental need, playgrounds should be provided for every child as much as schools. This means that they must be distributed over the cities in such a way as to be within walking distance of every boy and girl, as most children can not afford to pay carfare.”

London first witnessed the introduction of ‘junk playgrounds’ in the period following the Second World War, via the landscape architect and children’s rights campaigner Lady Allen of Hurtwood. She changed the name to ‘Adventure Playground’ in 1953 and, working with the National Playing Fields Association (now Fields in Trust), oversaw the coordination of adventure playground projects throughout the country. These playgrounds were constructed from recycled ‘junk’ which the NPFA provided in order for children to design and create playgrounds in spaces such as bomb sites, building sites and wasteland.

Since then, playgrounds have seen many design trends and playground design can now almost be seen as a form of artistic architecture. A good design is considered challenging but safe, aesthetically pleasing, cost effective and innovative.

The benefits of play for children is well articulated by a report by Stuart Lester and Martin Maudsley called ‘Play, Naturally’, commissioned by the Children’s Play Council. They concluded: “There is substantial evidence that supports the wide-ranging values and benefits arising from children’s play in natural settings. The powerful combination of a variety of play experiences and direct contact with nature has direct benefits for children’s physical, mental and emotional health. Free play opportunities in natural settings offer possibilities for restoration, and hence, well-being. Playful, experiential and interactive contact with nature in childhood is directly correlated with positive environmental sensibility and behaviour in later life.”

Access to playgrounds is usually limited to parents with young children but, regardless of that, they still form a vital and enjoyable part of the fabric of a happy and bustling open space.

Further study:

- Play Naturally, Stuart Lester and Martin Maudsley, Play England online 2007

- Cemeteries and churchyards

Starting in the early 19th century, the burial of the dead in graveyards began to be discontinued, due to rapid population growth in the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, continued outbreaks of infectious disease near graveyards and the increasingly limited space in graveyards for new interment.

7.1 Cemeteries

Instead of graveyards, completely new places of burial were established away from heavily populated areas and outside of old towns and city centres. Many new cemeteries became municipally owned or were run by their own corporations, and thus independent from churches and their churchyards. Non-conformists were often a driving force behind the development of early cemeteries as it meant that they could break free from the Church of England grip over church burials.

One of the first, The Rosary Cemetery in Norwich, was opened in 1819 as a burial ground for all religious backgrounds. Similar private non-denominational cemeteries were established near industrialising towns with growing populations, such as Manchester (1821) and Liverpool (1825). Each cemetery required a separate Act of Parliament for authorisation, although the capital was raised through the formation of joint-stock companies.

For hundreds of years, almost all London’s dead were buried in small parish churches. In the first 50 years of the 19th century the population of London more than doubled from 1 million to 2.3 million. Overcrowded graveyards also led to decaying matter getting into the water supply and causing epidemics. There were stories of graves being dug that already contained bodies, and bodies being flushed directly into the newly built sewer system.

Consequently in 1832 Parliament passed a bill encouraging the establishment of private cemeteries outside London, and later passed a bill to close all inner London churchyards to new deposits. Over the next decade seven ‘garden cemeteries’ (later dubbed the ‘Magnificent Seven’) were established: Kensal Green Cemetery, 1832; West Norwood Cemetery, 1837; Highgate Cemetery, 1839; Abney Park Cemetery, 1840; Nunhead Cemetery, 1840; Brompton Cemetery, 1840; and Tower Hamlets Cemetery, 1841.

The heyday of these cemeteries lasted until the death of Queen Victoria, after which there was a change in attitudes towards funereal ostentation, shaken further by the vast casualties of the First World War. As people spent less on their burials and more people were cremated, so these great Victorian cemeteries began a slow but steady decline. According to Darren Beach: “Many became badly neglected and developed into a bizarre form of urban forestry as they passed in and out of public, private and eventually council ownership. Several began to resemble overgrown gardens, with trees, ivy and shrubs allowed to run riot among the rows of headstones.”

Nowadays, most of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ are run by Friends’ Organisations dedicated to their restoration, conservation and maintenance. Some, like Abney Park in Stoke Newington, have been transformed into gleaming public parks with the aid of armies of volunteers and a supportive local borough council. Others, like Highgate’s untamed west cemetery, have been left to develop into peculiarly wild environments.

The appeal of Victorian cemeteries is well summed up by David Goode in his book ‘Nature in Towns and Cities’: “Those managing these old Victorian cemeteries today are faced with an extraordinary range of problems. They may have acquired a cemetery for next to nothing, but some are finding that the ongoing costs are enormous. But finance isn’t always the only problem. Nowhere is there a better example of conflicting interests than in these cemeteries. At one end of the spectrum there are those who are primarily concerned with protection and preservation of the historic monuments. For them the ivy is an anathema, to be removed at whatever cost. There are those for whom the local cemetery is their refuge from the city, cut off from the rest of the world. Some walk their dogs; some simply sit in quiet contemplation. Yet others see it as a place where nature can thrive in the midst of urban life. For some that means leaving it alone, undisturbed. For others it means detailed plans for individual species, with trees to be felled and grassland to be managed. Reaching agreement between these disparate groups demands much patience and diplomacy.” (p. 98)

Access to cemeteries is generally good, but they are typically very under-visited. Look carefully on the map or Google Earth and you will usually find more than one entrance, so you can plot a linear course through them.

Further study:

- The Victorian Cemetery, Sarah Rutherford, Shire Library 2008

- Paradise Preserved: an introduction to the assessment, evaluation, conservation and management of historic cemeteries, Historic England & Natural England, online 2007

- The Magnificent Seven, John Turpin & Derrick Knight, Amberley 2011

- London’s Cemeteries, Darren Beach, Metro Publication 2013

7.2 Chuchyards

An estimated two thirds of the Church of England’s 16,000 churches have churchyards which collectively cover the area of a small National Park. Many churchyards throughout Britain have now been designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest by English Nature

In the words of Churchcare, the Buildings’ Division of the Archbishop’s Council: “A churchyard is much more than a garden around a church. It is a burial ground, but also a place of quiet reflection and recreation, a habitat for rare plant and animal species, and the setting of the church building.” They have even published a book abut it: Churchyard Handbook – Wildlife in Church and Churchyard 2nd Edition

The good management of a churchyard needs to take into account a range of issues, from the burial rights of parishioners to the wildlife management of the churchyard. Taken together, churchyards make a significant area of land that has survived almost untouched by intensive agriculture and urban development over the centuries.

As years passed, and especially in the latter part of the 20th century, the churchyard wall or hedge took on a very important role as a ‘green protector’. In cities, urban sprawl engulfed many parish churches, but the churchyard within remained, creating a small oasis for plants and wildlife.

Richard Mabey writes in the ‘Unofficial Countryside’: “Churches and churchyards are double-strength sanctuaries for wildlife. They provide a refuge not just because of their mature trees and stonework, but because even the most wily schoolboy nester would think twice before pinching jackdaw’s eggs from under the sexton’s nose. The age and continuity of use of churchyards also gives them a chance to build up stable communities of plants.” (p.174)

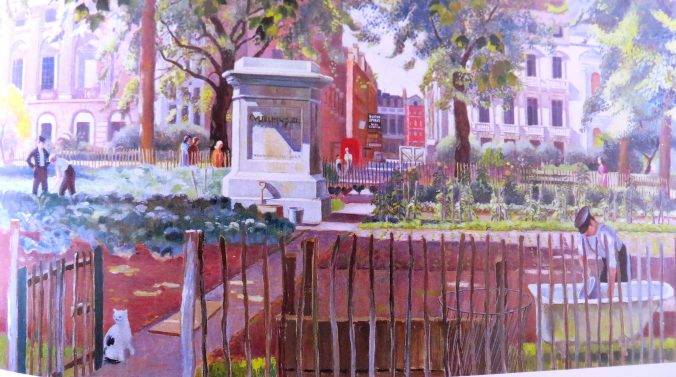

All churchyards are open to the public and often provide a welcome moment of repose in the midst of a city walk.

Cambridge churchyard in Portugal Place

Further study:

- Churchyard Handbook – Wildlife in Church and Churchyard 2nd Edition

C. UNTENDED GREEN SPACES

Intro

All that is needed for nature to thrive is water. As Richard Mabey puts it: “A crack in the pavement is all a plant needs to put down roots. An old-fashioned lamp-standard makes as good a nesting box for a tit as any hollow oak. Provided it is not actually contaminated, there is scarcely a nook or cranny anywhere which does not provide the right living conditions for some plant or creature.”

And in many ways, because untended spaces are just that – untended – they are typically pesticide-free, ‘un-ploughed’ and not subject to ‘improvement projects’ that wash away the nature. And usually untended spaces have an abundance of water in the shape of puddles and holes in the ground. So they are often very rich in wildlife.

The trickier issue inevitably is access. Wasteland almost always belongs to someone and is in the process of being re-developed in some way. So it can often only be observed from a distance and is by its nature ephemeral. But in any walk you take across a city, chances are you will come across at least one interesting derelict site that you might choose to poke about in.

- Disused railway lines

Railway lines changed the shape of cities in the nineteenth century, often forcing their way through to the centre by the widespread demolition of housing.

On one of our walks, along the Regent’s Canal, we see the gravestones that were removed from the original St Pancras Churchyard and laid against a tree when the St Pancras line was being cleared in the 1860s. Thomas Hardy, who was a young architect at the time, was in charge of the works.

As John R. Kellett points out in his book ‘Railways and Victorian Cities’, the railroad companies’ renewed and determined invasion of the central core of the Victorian city in the 1860s “ultimately had the effect of making them owners of between 8 and 10% of the most valuable central land, often with negative effects on both the companies themselves and urban life.” By 1890, Kellett reports, “the principal railway companies had expended £100 million, more than one eighth of all railway capital, on the provision of terminals, had bought thousands of acres of central land, and undertaken the direct work of urban demolition and reconstruction on a large scale.” (p.69)

Of course, this all went into reverse as a result of Dr Beeching’s cuts in the 1960s, which led to over a third of the railway network being axed, including many secondary urban lines.

Beeching’s reports made no stipulation for the handling of land after closures. British Rail operated a policy of disposing of land that was surplus to requirements. As a result, conversion to leisure use was very sporadic, until the Grimshaw Report in the 1980s. The report set out detailed proposals for the re-use of many disused lines. After that there was a more determined effort to re-utilise tracks for walking and cycling. The organisation that produced the Grimshaw Report metamorphosed into Sustrans Ltd., the Bristol-based path-building charity, and many of the proposals in the report were subsequently turned into successful railway paths throughout the UK. Some of the routes created now form part of the National Cycle Network.

This was achieved by the passion and commitment of many volunteers over the decades. There is even a Railway Ramblers Club, that can be found at www.railwayramblers.org.uk . The club’s main purpose is to bring together groups of like-minded people to explore old railways, but it has also done much to encourage the preservation of old railway lines as public footpaths and cycle ways. As railway enthusiasts will know, Dr Beeching and his successors axed about 8,000 miles of railways within the UK, but thanks to the efforts of local authorities and Sustrans (the charity behind the National Cycle Network); over 4,500 miles of this discarded network have been brought back into use as public walks and cycle trails. Happily, this mileage is increasing all the time.

Notable disused railway lines that you can now walk along in cities include:

- Bath to Bristol, a pioneering trail opened in the early 70s. This now accounts for over 2.5 million journeys per annum, split roughly equally between walking and cycling

- The Parkland Way, North London (pictured above)

- Wolverton to Newport Pagnell (Milton Keynes)

- Chorlton-cum-Hardy-Fairfield (Greater Manchester)

- Meadowhall Station (Sheffield) to Nr Ecclesfield

- Edinburgh (Holyrood Park Rd) to Brunstane

- Scottish Exhibition & Conference Centre (Glasgow) to Balloch

Further study:

- Railways and Victorian Cities, John R. Kellett, RKP 1979

- Vintner’s Railway Gazetteer, A guide to old railways you can walk along, Jeff Vinter, The History Press 2011

- Wasteland

Green spaces in cities have so often come as a result of ‘discontinuities’ in a city’s otherwise organic development; the Great Fire of London; the arrival of railways into town centres, the bombing of the Second Wold War, which levelled several city centres: the demise of railways and canals, leaving tracts of un-built on space; the decline in manufacturing; the redevelopment of The Olympic Park etc. etc.

Wasteland has that slightly eerie quality of land in-between times and in-between places, tranquil and becalmed whilst all around is going about its daily business. It is generally peered at through a broken piece of fencing or surreptitiously explored as a child despite the parental protestations that it’s a dangerous place. 24-hour security guards watch over it if you can believe the large-type, heavily underlined, part-capitalised ‘Trespassers WILL be prosecuted’ signs, but somehow they never seem to be there when you visit to prosecture you (or as I thought it meant when I was a child, ‘elecrocute you’ – maybe my parents had been happy for me to live with this misapprehension.)

As usual, it is Richard Mabey who most beautifully evokes the natural appeal of wasteland: “(Wastelands) are oases of real and provident country. They have cover, nesting sites, unchecked plant and insect life, and are rarely troubled by human visitors. It is amazing how romantic these pockets of ragamuffin greenery can begin to seem, nestling, like Frances Burnett’s Secret Garden, behind the factory walls. You may pass half-a-dozen every day and not be aware they exist.” (‘The Unofficial Countryside’, p. 48)

‘Edgelands, Journeys into England’s True Wildernesses’ by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts (a real cracker of a book, very thought-provoking), describes the modern, well, ‘edginess’ that wastelands evoke: “There are no signposts leading to the edgelands, no motorway signs with speed-legible Transport font and preordained background colour pointing us towards their fastnesses. Edgelands aren’t sites. They don’t behave like castles or bird reserves or historic market towns. Nobody asks, ‘are we there yet?’ (p. 185)

But perhaps you know a yype of space has really arrived when it has its own twinning association! Wastelands have just that, in the shape of the Wasteland Twinning Group (http://wasteland-twinning.net/) whose aim is to “subvert the City Twinning concept that aims to parade a city’s more predictable cultural assets and shift the focus to wastelands.”

They quote Noll and Scupelli (2009) who opine: “The voids of the city are spaces which disrupt the urban tissue, leaving it incomplete and throw into question the use of those spaces. Sometimes called urban ruins, they are at the limit between private and public space, without belonging either to the one or to the other. Urban voids are containers of memory, fragments of the built city and the ‘natural’ environment; memories of the city which constitute a random, unplanned garden.”

You and I might see it in a simpler way that that, but I get what they mean.

The amazing thing about wasteland/edgeland is how quickly it becomes ‘populated’ by man and animal once it comers into existence i.e. (paradoxically) derelict. First to arrive are the 4 by 4 bikers and the wild flowers; then the dog walkers and the skylarks and birds of prey – within two or three years the place is teeming with life, and will already be sadly missed when it inevitably reverts to new homes or offices, unless there is a ‘brown fields’ pollutant holding things up.

Further study:

- The Unofficial Countryside, Richard Mabey, 1973

- Edgelands, Paul Farley & Michael Symmons Roberts, Vintage 2012

D. WATER FEATURES

General intro

Richard Mabey writes: “Water, just as much in the shape of a rancid canal as a chalk stream between two villages, marks the edge of things. It is a barrier. It keeps people in their place. To a certain extent it also keeps nature in its place, and for some plants the thinnest strip of water can prove an impassable barrier. But it is also the life-blood of the natural world, irrigating the earth, providing food and drink for birds and animals, and for other plants a carrier service for seeds. The unofficial countryside is bountifully provided with water too, as so much of its land surfaces have been excavated, quarried, channelled and generally cut up.”

Water is a vital constituent in almost all of our walks too, providing a natural space to walk alongside, and often piercing through parts of a city in a way a normal path never could.

- Rivers

The Abercrombie Report (1944) had plenty to say about London’s rivers: “We’d like to see more of the river. London has a great asset in the Thames. Whole new stretches of the riverfront can be opened to the public.”

And since the post-war years, rivers throughout the country have generally been much improved, both in terms of their cleanliness and their leisure amenity value, with much better access.

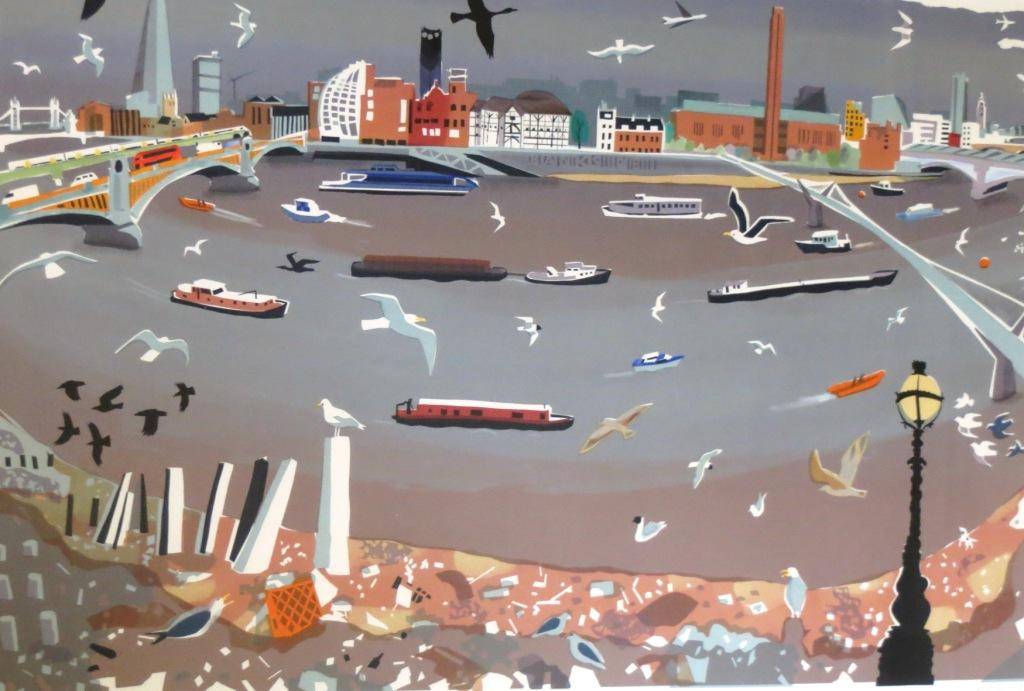

The Thames River is a great practical example. It won the International Theiss River Prize in 2010 in recognition of outstanding restoration. In 1957, the pollution levels had became so bad that the river was declared biologically dead. Fifty years on, the Thames has become a very different place. It teems with life: it has 125 species of fish, while more than 400 species of invertebrates live in the mud, water and river banks. Waterfowl, waders and sea birds feed off the rich pickings in the water while seals, dolphins and even otters are regularly spotted.

And in 1989, despite substantial resistance from landowners, the Thames Path was opened, giving access throughout its 213-mile length, of which 60 miles are through London. But the struggle between landowners never goes away completely, as you will discover on the stretch between Limehouse and City Hall, where the path is frequently disrupted by recent private developments. The waterfront always has value, be it commercial in the olden days or residential today, typically eliciting a 30%+ premium on the surrounding (inland-looking) properties.

Really making you feel at home (not)

When you can gain access, waterways are a great way to get ‘under the skin’ of a city and understand it better; also to imagine how it must have been in the past – after all, the river was there long before even one house had been built, often it was the reason that the city grew there in the first place.

Almost as interesting as the main rivers are the lost and culverted rivers – the clues lie in the squiggle of the street (think the sinuous Marylebone Lane and the River Tyburn), the exit culvert into the main river (Syon Park and Bollo Brook), the glimpsed torrent – this is the detective work that makes city walks so fascinating. One of our walks – the Sheffield Porter Brook walk – follows this stream from its source to its emission into the larger river by the station in the city centre. Another, in Belfast, gives you a glimpse of the River Farset, after which the city was named. Steffan Meyric Hughes, in his book ‘Circle Line: Around London in a Small Boat’, reflects: “The rivers live on in a sense: a plaque here, a street name there; a winding street that once followed its meanders down to the river; a boating or a swimming lake; a hinged iron door let into the embankment of the river.”

One note of caution: If you are planning your own urban ramble, study the map and Google Earth assiduously. We got very stuck on the final section of the River Lea as it approaches the River Thames, and ended up crossing a closed bridge (rotting and dangerous), scampering through a recycling plant and then walking through rather dull residential areas. Ah, the exciting life of an urban explorer!

Further study:

- Circle Line: Around London in a Small Boat, Steffan Meyric Hughes, Summersdale 2012

- London’s Lost Rivers, Paul Talling, Random House 2011

- Canals

The British canal system played a vital role in the Industrial Revolution at a time when long trains of packhorses were the only means of mass transit by road. Canal boats were much quicker, could carry large volumes and were much safer for fragile items. Canal mania took hold from the 1790s-1810s, but with the arrival of the railways from the 1830s onwards, the network fell into long term decline, ultimately leading to a complete re-think of their future role in the 1960s.

The Transport Act of 1968 was quick to recognise the value of the waterway network for leisure use, and set up the Inland Waterways Amenity Advisory Council to give advice to both government and British Waterways on all matters concerned with the use of the network for recreation. This was a much more pro-active plan than the disused railways had ever had; and combined with a more vociferous, active and passionate campaigning group, meant that much of the canal system has been successfully preserved for leisure – a jewel in the crown of Britain’s industrial heritage.

More recently there has also been a movement to redevelop canals in inner city areas, providing a focus for successful commercial/residential developments such as Gas Street Basin in Birmingham, Castlefield Basin in Manchester and Victoria Quays in Sheffield (all of which we go through on our walks).

Canals are not technically rights of way but, since nationalisation in 1948, they have generally come to be seen as free access. This was formally enshrined in the legislation which transferred responsibility for the English and Welsh canals from British Waterways to the Canal & River Trust in 2012. Access along canals is consequently very good.

One of the great features of canals running through cities is that when you use them you often feel like an interloper stealing up unawares on city dwellers, enabling you to observe secretly life as it’s really lived. There is an evocotive passage in ‘Slow Boat through England’, by Frederic Doerflinger, on rowing up the Regent’s Canal: “My wife and I sat in the stern of the dinghy, she trailing her fingers in the water and I myself looking up dreamily at the silhouette of the trees against the evening sky, amazed that such peace and beauty could exist right there in London. Only 30 feet above us the traffic was jammed motionless on Blow-up Bridge, but it seemed to belong to another world, incredibly remote. And so it did.”

Steffan Meyric Hughes, describes it beautifully too: “I realised that, with the help of a two-century old canal system and a small boat, it should be possible to sail and row around London, to float at less than walking pace through the magnitude of the city and view it from the perspective of its days of manufacture and commerce, to see how the old waterways had been deserted, becoming glimmering ribbons of solitude running through its brickwork like varicose veins cut off from the heart.”

Again and again I have found that canals are often vital stretches of accessibility when finding a route through a town centre – especially in the cities which industrialised most rapidly e.g. Manchester. So thank you canals, this book wouldn’t be possible without you!

Further study:

- Canals, the Making of a Nation, Liz McIvor, BBC Books 2015

- Find out more about the Canal & River Trust at https://canalrivertrust.org.uk/ why not join up and help support our canals?

- Slow Boat through England, Frederic Doerflinger, Comet 1986

- Conduits & millstreams

Conduits bring fresh water into a city centre from surrounding springs. They typically date from the pre-industrial period.

Hobson’s Conduit, for example is a watercourse that was built from 1610 to 1614 by Thomas Hobson and others to bring fresh water into the city of Cambridge. The scheme was first devised in 1574 by Andrew Perne, Master of Peterhouse, who proposed that a stream be diverted from Nine Wells chalk springs through the town and the King’s Ditch to improve sanitation. Walking alongside it makes a very interesting walk, particularly where it heads through allotments.

The Great Conduit was a man-made underground channel in London, which brought drinking water from the Tyburn to Cheapside in the City. In 1237 the City of London acquired the springs near the Tyburn and built a reservoir to provide a head of water for serving the city. Work on building the conduit began in 1245. It ran towards Charing Cross, along the Strand and Fleet Street and round the southern side of the city. It then ran along Cheapside where there was a building where citizens could draw water. Extensions were made to the system leading to various parts of the city. Other conduits were constructed in the 15th Century.

Millstreams channel water from a stream or river to provide water for a mill. In many cities, they were a vital part of the early industrialisation era before the arrival of coal. The Sheffield Porter brook walk is perhaps the best example of this.

Millstreams are recorded as far back as the Domesday Book, and from a topographical point of view they often lie at the upper edge of a meadow and define the green space on one side. They make charming routes to walk along.

- Dockyards & waterfronts

There are several cities we visit in the UK that owe much of their character to the dockyards that dominated them. Plymouth and Portsmouth as naval dockyards, Liverpool, Southampton as general dockyards, Cardiff as a coal dockyard, Hull as a fishing dockyard, to name but a few.

With the change in world trade patterns, decline in the fishing industry and the arrival of container ports nearly all these dockyards have shrunk and then closed. For many years afterwards they have been a blight on the waterfront, making it a no-go area for visitors. But starting in the 1980s, major re-generation projects were initiated in many of these former dockyard cities and their waterfronts transformed into multi-purpose leisure and residential use.

Two of the most notable were Cardiff and Liverpool. The Cardiff Bay Development Corporation was set up in 1987 to re-develop the dockyards and bay area.

The five main aims and objectives were:

- To promote development and provide a superb environment in which people will want to live, work and play.

- To re-unite the City of Cardiff with its waterfront.

- To bring forward a mix of development which would create a wide range of job opportunities and would reflect the hopes and aspirations of the communities of the area.

- To achieve the highest standard of design and quality in all types of development and investment.

- To establish the area as a recognized centre of excellence and innovation in the field of urban regeneration.

Whilst not all these goals have been met (see the chapter on Cardiff) many have.

The Liverpool Docks regeneration began with the listed Albert Docks, which had been derelict since 1971 but were not officially re-opened until 1984. Today the Albert Dock is the most visited multi-use attraction in the United Kingdom, outside of London. It is a key component of Liverpool’s UNESCO designated World Heritage Maritime Mercantile City and the docking complex and warehouses also comprise the largest single collection of Grade I listed buildings anywhere in the UK. Since then, on-going developments have continued to transform the waterfront and made it an integral part of Liverpool’s appeal as a vibrant, cultural city.

Walking through regenerated waterfronts is almost always a highlight of a sea-based city, and access is usually very good. Sometimes it is poorly integrated with the city centre, which is the case with Cardiff but definitely not with Liverpool.

E. NATURAL GREEN SPACES

- Meadows

Most of the meadows we visit in these city walks are water meadows, adjacent to rivers. They almost always have good access, providing you have waterproof footwear and are not bothered by cows. Cambridge is especially notable for its meadows, which form a delightful back-drop to the architecture of the colleges.

Oxford’s Port Meadows

The upkeep of water meadows in urban areas has become a greater burden as farmers have become more reluctant to take their cows there for pasture. They are put off by the difficulty of herding the livestock through busy streets and the nuisance of dogs. The grazing is key to keeping the vegetation in check and the grasses thriving. In some cases Friends’ groups have stepped in and arranged for the meadows to be mown each season instead.

Further study:

- Meadows, George Peterken, The British Wildlife Collection 2013

- Heaths

First of all, what constitutes a heath? The definition reads: an area of open uncultivated land, typically on acid sandy soil, with characteristic vegetation of heather, gorse, and coarse grasses. So pretty much the opposite of a water meadow. We come across heaths pretty infrequently on our walks – and the most famous of those by far is Hampstead Heath.

Hampstead Heath dates back to the Domesday Book but, like so many of London’s open spaces, was subject to several attempts to build on it during the 19th century as the pressure for housing grew. As a result of campaigning by the Commons Preservation Society amongst others, it was finally bought for the nation in 1871 and has remained intact ever since. Any proposed changes tend now to meet with vociferous opposition from the locals, who see it as their own – which is just what you want people to feel about their local space.

- Woodland

Trees play a key symbolic role in our lives as a direct connection with nature. And the benefits of trees in cities are well-documented, both for their aesthetic and environmental properties. People can form close personal attachments to individual trees.

Trees are also perfect for creative play: “Trees can be climbed and hidden behind; they can become forts or bases; with their surrounding vegetation and roots, they become dens and little houses; they provide shelter, landmarks and privacy; fallen, they become part of an obstacle course or material for den-building; near them you find birds, little animals, conkers, fallen leaves, mud, fir cones and winged seeds; they provide a suitable backdrop for every conceivable game of the imagination.” (Ward 1988)

15% of all woodland in the England is estimated to be within cities. On average 12.5% of the UK is wooded, and incredibly so is 8.5% of London (and this doesn’t include individual trees).

Our walks take us through several woods, from the extensive woods of Sheffield’s Porter Brook to the small but perfectly formed Clare Wood in the Cambridge suburbs. But whatever size they are, they allow you to escape entirely from the ‘city’ and to imagine yourself in deep countryside, where the next thing that comes round the corner is as likely to be a deer or a squirrel as a jogger.

Further study:

- http://www.treesforcities.org/about-us/who-we-are/vision/

- Urban health and the role of urban forestry in Britain: Forestry Commission, online

- London’s Urban Forest: A Guide for Designers, Planners and Developers, online

F. CONTROLLED GREEN SPACES

- The Green Belt

England’s fourteen Green Belts cover nearly 13% of England, significant not only because of their extent (covering a slightly greater area than all our national parks), but because they provide a breath of fresh air for 60% of the population – 30 million people – living in the urban areas within Green Belt boundaries.

The purposes of Green Belts in planning policy are clear – to protect the countryside from urban sprawl and to retain the character of towns and cities. To this end they have been effective.

The concept had its roots in Ebenezer Howard’s 1898 vision of Garden Cities, providing people with space to enjoy the beauty and tranquillity of the countryside nearby. These ideas evolved in the 1920s with campaigns seeking a clear physical distinction between town and country.

Implementation of the notion dated from Herbert Morrison’s 1934 leadership of the London County Council. It was first formally proposed by the Greater London Regional Planning Committee in 1935, “to provide a reserve supply of public open spaces and of recreational areas and to establish a green belt or girdle of open space”. It was again included in an advisory Greater London Plan prepared by Patrick Abercrombie in 1944 (which sought a belt of up to six miles wide). However, it was some 14 years before the elected local authorities responsible for the area around London had all defined the area.

New provisions for compensation in the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act allowed local authorities around the country to incorporate green belt proposals in their first development plans. The codification of Green Belt policy and its extension to areas other than London came with the historic Circular 42/55 inviting local planning authorities to consider the establishment of Green Belts. This decision was made in tandem with the 1946 New Towns Act, which sought to depopulate urban centres in the South East of England and accommodate people in new settlements elsewhere. Green belt could therefore be designated by local authorities without worry that it would come into conflict with pressure from population growth.

A survey by Campaign to Protect Rural England shows that 95% of people value the beauty of the Green Belt and 58% have visited for leisure in the past 12 months. 44% of England’s Country Parks and 33% of Local Nature Reserves are in Green Belts – and 19% of England’s ancient woodland is in the Green Belt. Nonetheless the debate rages on about their overall value – some say that they are at the root of the country’s endemic housing shortage, and others that the land is often uninviting and offers few nature benefits.

Not many of our walks go through green belts as we tend to stick to the centre of cities; the notable exceptions being Oxford and Cambridge where the Green belts lap up to the meadows across which we walk.

Further study:

Further study:

- Green Belts: a greener future, Campaign to Protect rural England & Natural England, 210, online

- Urban Regeneration in the UK, Andrew Tallon, Routledge 2010

- Nature Reserves

Nature reserves offer oases of tranquillity and natural life within a city and are sometimes found in the most unlikely places. Many of our walks pass through a nature reserve along the way, and they always add greatly to the pleasure of the experience, be they the wildness of Cardiff Bay’s Wetland Reserves or the tiny 2-acre Camley Street Nature Reserve alongside the railways line and canal in King’s Cross.

City authorities have given a high priority to supporting nature reserves within their boundaries. Plymouth has 10, for example and Oxford manages over 900 acres of SSIs (sites of special scientific interest). London has 140 Local nature reserves and 45 London Wildlife Trust reserves. The London Wetlands Centre (40 hectares, 100 acres) is one of the biggest schemes in Europe.

Further study:

- Nature in Towns and Cities, David Goode, William Collins 2014

END

3rd January 2022 at 11:12 am

The author of this publication is NicholasRudd-Jones. thank you.