Cidade Maravilhosa: purgatório da beleza e do caos

Marvellous City: purgatory of beauty and chaos

Most Urban Rambles are concerned with classic motifs of British cities like Georgian architecture, Victorian parks and post-war urban planning. Rio de Janeiro is a thousand miles from this, literally and figuratively: colonial and modern architecture is meshed with rainforest, sand and sea, in a landscape which looks like Christ the Redeemer painted it with his own fair hand. There is a certain musicality in the air: everything in this city seems to move either to the frenzied beat of the samba drum or the relaxed guitar of a bossa nova. Cariocas of all ages, classes and races seem to sweat culture out from every pore, and by the end of this walk, you will too!

WALK DATA

Distance: 7.5km (4.7 miles)

Height Change: considerable, but only in Santa Teresa. (If you wish to cut out the hills, follow the Rua da Lapa all the way to Glória and ignore the instructions in step 6).

Typical time: 3 hours

Start: Pedra Do Sal, Rua Argemiro Bulcão, Saúde

Finish: Largo do Machado, Catete

Terrain: (dodgy) pavements throughout, sturdy shoes recommended

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Parque do Flamengo, Praça Mauá, Ipanema, Copacabana and Vermelha beaches, Morro da Urca nature reserve, Parque Lage, Jardim Botânico, Tijuca National Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Lagoa Rodrigo Freitas, Atlantic Ocean |

| Stunning cityscape | Vista Chinesa, Morro da Urca and Sugarloaf, Christ the Redeemer, Morro Dois Irmãos/Vidigal favela, Mirante Dona Marta, Parque das Ruínas |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Colonial Architecture (1500-1822) | Parque Lage mansion, Nossa Senhora de Glória church, Nossa Senhora de Candelaria church, Teatro Municipal, |

| Modern (1945-) | ‘Calçadão’ (pavement) of Copacabana and Ipanema, Museu de Arte Contemporânea (Niterói), Museu de Arte Moderna, Museu do Amanhã, Museu de Arte do Rio, Maracanã, Metropolitan Cathedral, Petrobras Building, Sambodrome |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Confeitaria Colombo, Parque Lage Café, Armazém São Thiago, botequins and street food |

| Quirky Shopping | Markets (Santa Teresa and Praça General Osório, Sundays), Uruguaiana Market, Ipanema and Copacabana beaches |

| Places to visit | Museu do Amanhã, Museu do Arte do Rio, Museu Contemporânea de Niterói, boat to Niterói at Praça XV, Sugarloaf, Ipanema Beach, |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Reveillón (New Year’s Eve), Carnaval (February), Festas Juninas (June), Rock in Rio (September), |

City population: 6.32 million (2010 census)

Ranking: second biggest in Brazil

Date of origin: 1565 (previously inhabited by various indigenous peoples, and first encountered by the Europeans on 1 January 1502, hence the name ‘January River’).

‘Type’ of city: slave port, former capital of Brazil (and at one time, the Portuguese Empire),

Some famous inhabitants: Chico Buarque (musician), Heitor Villa-Lobos (composer), Hélio Oiticica (artist), Jorge Ben Jor (musician), Machado de Assis (author), Oscar Niemeyer (architect), Paulo Coelho (author), Ronaldo (footballer), Tom Jobim (musician, founder of Bossa Nova), Vinicius de Morães (musician), Carmen Miranda, Seu Jorge (musician), Rafaela Silva (Olympic gold medallist, judoka)

Notable city architects / planners: Oscar Niemeyer, Roberto Burle-Marx, Affonso Eduardo Reidy

Films/TV series shot here: City of God (2002), Black Orpheus (1959), Rio (2011 – cartoon), Elite Squad (2011), Central Station (1998), Favela on Blast (2008), Moonraker (1979).

CONTEXT

Europeans first entered Guanabara Bay on New Year’s Day, 1502, and, falsely believing the enormous inlet to be a river, named it ‘Rio de Janeiro’, or January River. For much of its early colonial history, the capital of Brazil was Salvador, in the northeastern state of Bahia, but in the mid-eighteenth-century the discovery of gold and diamonds in the neighbouring state of Minas Gerais launched Rio as the country’s principal port.

While the colony sent enormous quantities of precious metals and stones back to Europe, it also imported a more precious cargo: human beings. Few people realise that Rio de Janeiro was the biggest slave port in the Americas – indeed, it is the most prescient aspect of the city’s history and one which has marked the landscape indelibly.

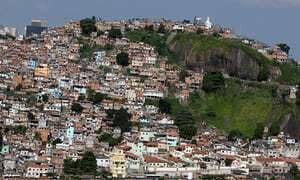

Rio residents are divided between those who are ‘of the hill’ and ‘of the asphalt’, meaning people who go about their lives in the ad hoc favela communities dotted throughout the city, and those who conduct their business on the gridded streets of the South Zone. This disjuncture between two populations, inhabiting two different cities side-by-side, is essentially a replication of the division inherent in postcolonial society.

The marriage between Rio’s history and its physical geography is at the very heart of its urban story, and its incredible hills have been just as influential in this tale as the Atlantic sea coast. Rio was in fact the site of a French Huguenot colony, France antarctique, from 1555 until their expulsion by the Portuguese in 1567. The Governor-general of Brazil, Mem de Sá launched his military campaign from the Morro do Descanso, or ‘hill of rest’, which was razed in 1922. Four centuries later, the hilltop neighbourhood of Santa Teresa was a bastion of liberal opposition to the military dictatorship – popular because it resembles a rabbit warren, and so it was much easier to escape the police down one of its alleys, than on the gridded streets below.

Of course, Rio’s most famous hills are the Corcovado mountain, with Christ the Redeemer standing proudly atop it, and the iconic Sugarloaf. These picture-postcard images are now one of the city’s key exports, as tourism plays a crucial role in its economy. The hillside favela communities are also the beating cultural heart of the city, responsible for musical innovations such as funk carioca and of course, samba.

In turn, the asphalt represents the planned urban landscape as it competes with the Atlantic tide. The spontaneous ingenuity that characterises the unregulated landscape above gives way to the Aterro do Flamengo (which was reclaimed from the bay, using the earth from the demolition of the Morro do Castelo). This is where the bourgeoisie made their mark, attempting to create their own version of Paris in the tropics, complete with the institutions befitting of a modern city – theatres, a national library, museums housing fine art and, of course, a botanical garden.

In addition, the city was to have the ‘mod cons’ which Europeans from Lisbon to London had grown accustomed to: trams and buses (albeit pulled by animals), railways and steamboats, street lighting, a telephone service and a sewage system.

In the period from the dawn of the Republic in 1889 to the mid-twentieth century, the population of Rio tripled, its numbers swelled by domestic migration. The most influential president in Brazil’s history, Getúlio Vargas, saw industrialisation as the key to Brazil’s ascension into the pantheon of developed nations. However, just as had happened during the Industrial Revolution in cities like Glasgow and Manchester, slum settlements spread rapidly and the city grew to be increasingly defined by its inequality.

Nevertheless, one thing will always unite Cariocas from all walks of life and that is the beach. While on this occasion it isn’t green, shared urban space is again a catalyst for civic conviviality. Without further ado, let’s explore!

THE WALK

We begin our walk in the neighbourhood of Saúde, known as ‘Little Africa’, owing to its slave-trading history and the vibrant cultural output of those who were brought here by choice or by force. Some four million Africans were kidnapped and brought to Brazil during the slave trade and most would have embarked at the Valongo Quays, the remains of which were discovered during construction for the 2016 Olympic Games, and were recently named a Unesco World Heritage Site. Slaves would then be auctioned off at the Pedra do Sal, or salt stone (named after its earlier purpose, a place to dry imported salt ready for sale). Pedra do Sal is also the site of a quilombolo community. Quilombos are settlements built by fugitive slaves all over Brazil, many of which survive to the present day, despite legal and socio-economic forces which would rather see them perish.

The ruins of the Valongo Quays

The Quays are recognised as a Unesco World Heritage Site

Quilombos endured as safe(r) places for Afro-Brazilians to live and practise their customs, even as persecution continued well after the abolition of slavery in 1888. For example, an important mode of survival for ex-slaves known as capoeira was banned under the Old Republic (1889-1940) because it was perceived as a threat to the order of things established by elite oligarchic rule. Capoeira is a method of self-defence used by slaves to escape and then establish quilombos. As slaves could not be seen to be preparing to escape, they concealed the defensive nature of capoeira by including elements of dance, fooling their masters and creating a cultural tradition which endures to the present day. The other defensive aspect of Pedra do Sal and its environs is that it is a steep hill, which provided an escape for Black Brazilians for persecution inflicted on them by other citizens and agents of the state, who were rarely interested in chasing them up the hill.

The quilombo of Pedra do Sal also provided a space for this population to practise candomblé, a syncretic religion which includes elements of Catholicism, indigenous traditions and Yoruba, Fon and Bantu beliefs which slaves brought with them from West Africa. Like capoeira, candomblé became the object of police ‘interest’ as the vehicle for meetings of ex-slaves, and thus something which bound Afro-Brazilians together. Within candomblé, there is no duality of good and evil, but rather each person must fulfil their own destiny, whatever it may be. This belief has permeated Rio’s psyche to an extent – sometimes your destiny might be to wait an hour for your dinner in a café where the waiter is working on carioca time! It is also an oral tradition, with no written scriptures and music at its heart – ‘macumba’ is a Brazilian term of Bantu origin which means both ‘music’ and ‘magic’.

The candomblé tradition is also the root of samba, especially the samba de roda (or ‘dance circle’) genre which is still played every Monday and Friday night at Pedra do Sal. Apart from Carnaval, this is the most traditional street party in Rio and one which is as popular with locals as it is tourists. Street-vendors sell caipirinhas, beer and churrasco (barbecue) and everyone is dancing, whether it be to the samba, outside a lively bar down the street or to the reggae up the hill – it is certainly not to be missed!

A peaceful Pedra do Sal by day…

…and by night

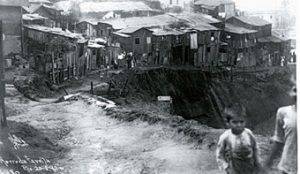

As well as the slaves that arrived in this area after abolition, there was huge domestic migration from the northeastern state of Bahia, where the plantation economy was based on coffee and took a substantial hit after the Wall Street Crash. This gave rise to the construction of the first favela, Morro da Providência, in nearby Gamboa. The first settlement was built by veterans of the Canudos War which took place in Bahia in 1896-7; they had been promised land to build houses upon arrival in Rio but when they arrived (on foot), they were denied by the Ministry of War. The soldiers protested on the hill opposite the Ministry and 120 years later, the settlement is still there. They named the hill after favela, a plant indigenous to the Canudos region where they had been fighting, but when hundreds and then thousands of other such settlements sprang up, the name was changed to ‘Providence’.

NB: It wouldn’t necessarily be wise to combine urban rambling with most favelas, so our walk doesn’t include any, though they form an important part of the city’s history and culture. You can find out more about favela history here; Rolé dos Favelados is an ethical tourism organisation run by residents.

Walking back into town, our walk takes a turn from a DIY culture of survival in the face of slavery and repression, to the Porto Maravilha zone which is the main urban legacy of the 2016 Olympic Games, symbolising the globalisation and state funds which favela residents don’t typically benefit from. Previous to the municipality’s intervention, the area had fallen prey to the usual plagues of ports – bars, brothels, and criminality. Praça Mauá, the square between the sea, the port and Avenida Rio Branco now recalls the sort of pristine European urban regeneration we have seen in places like Kings Cross. This is unique in Rio and has the distinct air of having been built for international tourists’ photo opportunities rather than residents’ recreation. Similarly, the nearby Boulevard Olímpico was transformed into a globalised capitalism-fest during the Games, with old warehouses full of branded experiences by the likes of the NBA and Coca-Cola, which had very little to do with Olympic values. Still, the warehouse buildings played host to enormous works by Brazilian graffiti artist Kobra, paying tribute to the native creativity of the district.

It was feared that the regeneration of the area would launch a tide of gentrification and that the remnants of the history of slavery would be brushed under the rug for the purposes of Olympic optics. Nevertheless, the collections of the MAR (Museu do Arte do Rio) on the praça pay tribute to various experiences of carioca life. Whilst the contents of the museum are unmissable, the building itself is a work of art. Completed by local firm Bernandes + Jacobsen in 2013, it unites various existing structures with an enormous roof in the shape of a wave, from which visitors can take in a glorious view of Guanabara Bay.

Across the square, the Museu do Amanhã (Museum of Tomorrow) also hides an incredible vista. Inside, the Museum provokes visitors to consider what they are doing for our planet’s tomorrow, and to queue up for a very long time to get photos of them pretending to hold the whole world in their hand.

A more historic building on the square is the Edificio Joseph Gire (1930), headquarters of the nightly newspaper A Noite. The Art Deco behemoth is more akin to something one would expect to find in Chicago, much unlike the European styles which were traditionally favoured in the city.

From here we head down Avenida Rio Branco, one of the city’s principal boulevards and the main hallmark of the prefect Pereira Passos’ regeneration plan of the early Twentieth century. We end up at Candelária church, one of the most beautiful in Rio where a variety of Rococo, Neoclassical, Baroque and Art Nouveau architectural styles mesh together without seeming in conflict. Its origin story is also rather romantic: legend has it that a ship carrying a Portuguese couple to Brazil was shipwrecked here. To give thanks to God for their survival, Antônio Martins de Palmeira and Leonor Gonçalves built the church, named after the ship they had travelled on.

Continuing through the downtown district of Centro, we reach Praça XV de Novembro – named after the day of the proclamation of the Republic. Nevertheless, the square is more closely linked to the city’s imperial history, and indeed the genesis of Brazil as a country. The most imposing and eye-catching building in the plaza is the Paço Imperial, built in the 18th century for Brazil’s colonial governors to reside in. The very first building in the entire city to have glass windows, it is one of the most important examples of colonial architecture in Brazil, typifying the Baroque style native to Northern Portugal.

Jean Baptiste Debret’s etching of Praça XV

The Paço Imperial

The palace was never intended to be the home of a king, but that is exactly what happened when Dom João VI arrived in Rio in 1808, bringing the entire royal court with him. Why this transatlantic move, I hear you ask? Well, in what sounds like an early precursor to the Carry On films, the entire Portuguese monarchy was forced to flee Napoleon’s advancing armies and so Rio became the seat of the Portuguese Empire until 1822, when Brazil claimed its independence.

Another architectural treat brought over by Portuguese immigrants is the delightfully continental Confeitaria Colombo, a Belle Époque coffee house later renovated in an Art Deco style. Famous clients include past presidents, the composer Heitor Villa-Lobos and even our very own Elizabeth II. If it’s good enough for her, it’s good enough for a hungry rambler – our pick would be the bolinho de bacalhau, followed by an achingly sweet brigadeiro.

The café will spit you out into bustling Largo da Carioca, the original nucleus of the city in the sixteenth century when this now vibrant marketplace was but a lagoon. The name ‘carioca’ comes from the river which fed this swamp, now canalised onto the Arcos da Lapa. If you’re here for a moment, you’ll see the (free) tram precariously traversing the 270m-long aqueduct as it makes its ascent to the hilly district of Santa Teresa, where we’re heading later. The etymology of carioca is from the Tupi language, meaning ‘house of the white man’. The word has now become the demonym for Rio’s citizens, and as such a by-word in the rest of Brazil for anyone given over to partying but less-so to punctuality.

Towering over the square are two incongruous modern buildings, both dating from the Seventies and with incredibly different purposes. The Brutalist behemoth is the Petrobras headquarters – what irony that an architectural style borne of a rejection of frivolity houses an organisation which symbolises corruption and decadence in Brazilian society!

Across the way is the city’s cathedral, built in a modernist take on Mayan architecture, mimicking a pyramid. The scale is staggering – it has 5,000 seats, with a standing capacity of 2,000, and its four stained glass windows are 64m tall.

Metropolitan Cathedral – Edgar Fonseca (1979)

Petrobras Building – Roberto Luis Gandolfini (1972)

From here, our route skirts the edges of the Passeio Público park, the first public park in Brazil, and indeed most of the Americas. Nevertheless, on the occasion of its inauguration in 1779, it was walled and open only to the upper echelons of society until it became public in 1793. Like many of the other city improvements of this era, it mimicked what the Europeans were doing, and so was built in a French formal style. In the 1950s it took on a new lease of life as a centre of nightlife and culture, and the area remains the place to be if you want to drink a very large and very cheap caipirinha whilst listening to some spontaneous street samba.

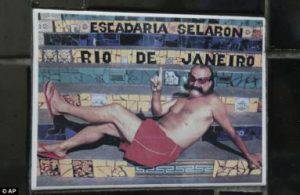

Now we begin the aforementioned ascent to Santa Teresa. Now, this could be rather an unpleasant experience, given the heat and the climb involved, if it were not for the art of a Chilean man by the name of Jorge Selarón. Beginning in 1990, he started to decorate the steps outside his front door with small pieces of tile in the colours of the Brazilian flag (blue, green and yellow). His neighbours lambasted him for it but he soon became obsessed and as soon as one section was finished he would extend to another section, selling paintings to finance the project and declaring that the work would only be finished when he died. Bizarrely, the prophecy came true and he was found dead on the steps one January morning, his body burnt and drenched in paint thinner; the police didn’t rule out homicide.

This 125m-long ribbon of colour linking Lapa to Santa Teresa is unmatched in the city as a civic work of art, but this bohemian neighbourhood up above is host to a number of beautifully painted staircases. It’s a typically carioca way to make art – using the functional canvas of the cityscape and giving it a new lease of life which is accessible to all as people go about their quotidian business.

Here’s a handy key to some of Rio’s other beautifully colourful staircases:

Photo credits: Julihana Valle

For the less-keen hillwalkers among us, the tram is a handy way to scale the hill, and has been since 1877, making it one of the oldest trams in the world. Rio’s landscape demands innovative modes of public transport, including cable cars (to the Sugarloaf, Corcovado and Complexo de Alemão favela), mototaxis (take your life in the hands of a young man driving a motorbike up a steep and winding hill) and combis (the same, but in the comfort of a crowded VW camper which would definitely not pass an MOT).

This district was built up around the Santa Teresa convent from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. Its opulent villas are testament to its origins as an upper-class borough – the wealthy flocked here to avoid an epidemic of Yellow Fever, as in Buenos Aires’ Barrio Norte and no doubt countless other tropical cities.

For the last century or so, though, ‘Santa’ had ceased to be associated with the upper crust. Instead, it became a renowned gathering place for academics, intellectuals, artists and dissidents attracted by the architecture and character of the place – as well as the fact that it is somewhat of a hilltop rabbit warren, easy to escape from when the military police came knocking.

Its most famous resident was one Ronald Biggs, who was fugitive here from 1970, though he most certainly didn’t lead a low-key life: he played and sang in various bands locally and had a child with a Brazilian to avoid extradition.

It’s easy to see why Ronnie chose to make this particular nook of Brazil his home – it really does feel like a verdant village away from the occasionally unsavoury goings-on of the city below. It’s also a gastronomic and cultural centre, and as such has begun to gentrify quite significantly in the past decade or so. The city government has encouraged this, building walls to stop the spread of nearby favelas and implementing utility taxes designed to keep any lower-income residents at bay.

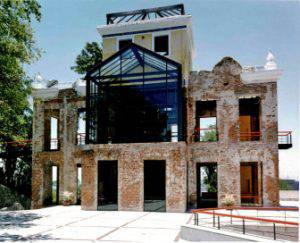

A building which typifies Santa Teresa’s story of grandeur, dereliction, and then redevelopment for the benefit of the middle classes is the Parque das Ruinas, former home of heiress Laurinda Santos Lobo. The mansion fell into disrepair (hence ‘ruinas’) for some forty years, during which time the property was frequented by drug dealers and beggars who stole each and every one of the gold door knobs. In 1993, the city government purchased it and organised an architectural competition to restore it, won by Ernani Freire.

Whilst Santa Teresa and the park itself are becoming increasingly popular with tourists, this is still one of the best spots to get semi-uncrowded panoramic views of the city and the bay. In the evenings, it also plays host to series of concerts. I can most certainly attest to the intoxicating combination of a Santa sunset and a samba band…

Descending on the windy Rue Cândido Mendes, we eventually find ourselves in the district of Glória. Originally a Tupinamba village, it soon became a battleground between the indigenous population and the Portuguese colonialists and was where the city’s founder, Estácio de Sá, died in battle. The area takes its name from the conveniently-named Nossa Senhora da Glória de Outeiro church, where exiled king Dom João VI went to mass. Another jewel in the colonial architecture crown, the church was consecrated in 1739, making it practically ancient in New World terms.

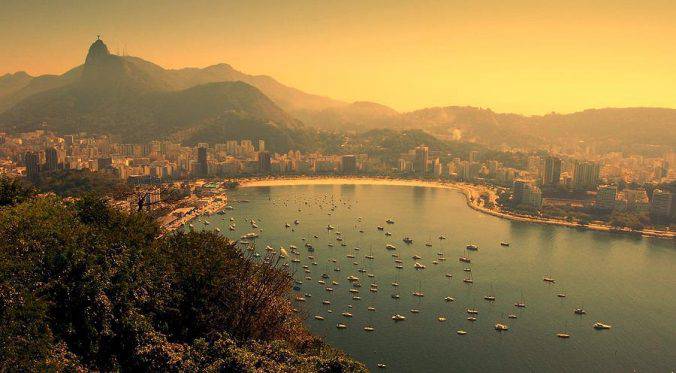

In the centuries since it was built, Nossa Senhora da Glória’s view has changed dramatically. Strips of reclaimed land, or aterros, have gradually pushed the bay further and further away over the last 100 years, making way for quicker and wider roads linking Centro to the South Zone, but also a considerable amount of green space. You can get an idea of the scale of these works here.

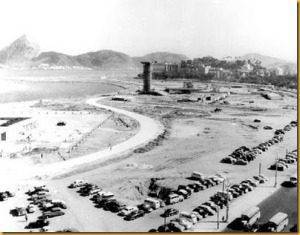

The aterro during its construction c. 1960

and nowadays

The 265 acres of the Parque do Flamengo were completed in 1965 and constitute a real achievement of urbanism, built on an extraordinary example of civil engineering. Their creation was sponsored by one Maria Carlota de Macedo Soares, who saw the gardens as an opportunity not just to create a nice park of fountains and playgrounds, but a space which would improve quality of life, stop the advance of property developers towards the sea, and help citizens to reconcile themselves with urban space.

The gardens are the work of Roberto Burle Marx, a man credited with bringing modernist landscape architecture to Brazil and responsible for one of the city’s most well-known urban motifs, the Copacabana calçadão (pavement). In fact, this classic pattern of pedra portuguesa (‘portuguese stone’, or tiled pavements) has its origins in the neighbourhood of Rossio in downtown Lisbon. Burle Marx sought to extend it and keep it in line so it always reflected the waves crashing onto the beach.

The endpoint of our ramble will be Largo do Machado, a meeting point between the neighbourhoods of Catete, Flamengo and Laranjeiras, constantly thronging with cariocas of all walks of life as they go about their business in the city. It’s had many names in its history, but most (wrongly) believe it to be named after the best Brazilian writer, Machado de Assis. His œuvre calls to mind the Bohemia of old Rio just as the architecture of the square does. His reimagination of European literary traditions adapted for the tropics mirrors the objectives of Rio’s architects and planners – and, at the end of our ramble, I’m sure you’ll agree that they succeeded in creating a most fascinating city.

A note on safety: All of the usual tenets of tourist safety apply in Rio: don’t wear jewellery, don’t take money you’re not prepared to lose, don’t flash your camera about and keep your wits about you. If you are unfortunate enough to be robbed, just hand everything over. Don’t worry, but also don’t be complacent!

THE ROUTE

- Coming out of the courtyard where Pedra do Sal is, head right down São Francisco da Prainha towards the main road). When you reach a small sort of square, bear right down Sacadura Cabral towards Praça Mauá (invariably, this will have been how you arrived at Pedra do Sal in the first place).

- You will probably want to take in the view and museums in Praça Mauá, but when you are ready to move on, bear right down Avenida Rio Branco (following the tram tracks). When you reach Avenida Presidente Vargas (a massive thoroughfare, you won’t miss it), turn left and walk behind Nossa Senhora de Candelaria church until you reach Rua Primeiro de Março.

- Reprising your original direction, take Primeiro de Março in parallel to Avenida Rio Branco. Eventually you will find the expansive Praça XV to your left and beyond that, the Bay of Guanabara. Once you’ve had a good look round, strike off left down Rua Sete de Setembro.

- Continue down this narrow side-street for five blocks. At the fifth right turning (just after Confeitaria Colombo on your right), turn left towards Carioca station (there’s plenty of signs here, it’s easy to see the square where you enter the metro).

- Across the square, you will hit an avenue, with the Petrobras building looming over you on your right. Walk towards it, turning left just before you get there down Rua Sen. Dantas. There is an Itaú bank at the end of the street, when you reach it, turn right again onto Evaristo Veiga and head down into the square below the Lapa arches. There is usually a police presence but keep your wits about you here.

- Follow Avenida Mem de Sá to the left, and then strike off right on Teutônio Regadas – you’ll see the Escadaria Selarón at the end.

- Take the steps and then Ladeira de Santa Teresa upwards and to the left (strongly recommend a chilled coconut at this juncture!). At the top, turn right onto Rua Dias de Barros and admire the view to your left. Bear right and follow signs to Parque das Ruínas, or continue along to the bonde stop on the curved junction (Largo do Curvelo). Here, take Rua Bernadino dos Santos to the left (it’s a small lane sloping upwards). Following this as it becomes Rua Cândido Mendes and winds its way down to Glória. As you reach the bustling Rua da Glória, walk right towards the metro station. Seeing the Glória church on the hill above you, make your way there via Ladeira da Glória. Follow the lane around the church as it becomes Ladeira da Nossa Senhora and then Rua do Russel.

- Eventually, you will reach the Parque do Flamengo; walk through the park or on the beach up until Rua Machado de Assis. Here, turn right up the street until you reach the large square of Largo do Machado, where our walk finishes.

PIT STOPS

A Rio institution and real colonial throwback, this café is a fin-de-siècle gem right in the centre of the city. Its clientele includes former presidents Getúlio Vargas and Juscelino Kubitschek, as well as our own Queen. Tip: stay away from the ‘proper food’ and stick to coffee and patisserie.

Another institution founded by European immigrants, this pub in the heart of Santa Teresa is the epitome of the botequim. The coldest of lagers and the warmest of bolinhos de bacalhau (salted cod and potato fritters) are best accompanied by a football match, but there is always a fantastic atmosphere here.

Street Food

One of the most joyous things about living in Rio for me was the availability of food wherever you are! On the beach you can get your hands on everything from barbecued prawns to ice cream; on the pavement it’s all about a warm churro piped full of steaming hot doce de leite (dulce de leche) or a tapioca pancake (sweet or savoury). There are also no regulations on selling alcohol informally, so you can crack open a chilled Brahma whenever. I would advise caution with regards to the consumption of caiprinhas on the beach though – they’re a lot stronger than they taste!

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Sunday Market at Praça General Osório, Ipanema

I would thoroughly recommend this market for souvenirs. Jewellery, clothes and accessories are abundant but the stand-out for me is the cheap, colourful paintings of classic Rio scenes. Buy a canvas for a bargain-basement price, roll it up in your suitcase, and get it framed back in the UK.

Uruguaiana Market

First and foremost: keep an eye on your bag here. Be prepared to haggle too, if you have any rudimentary Portuguese. This is where Brazilians buy dirt-cheap clothes and while the fashions are unlikely to be to your tastes, it is a good bet for football tops, Brazilian flags, and other bits of holiday memorabilia!

The beach

What you can’t buy on the beach in Rio probably isn’t worth having! Each day, an army of entrepreneurial cariocas descend from the hills and North Zone to ply their wares on the golden sands of Ipanema and Copacabana. As I mentioned, food and drink is the clear stand-out but you can also get no end of bikinis, jewellery, selfie sticks and fake sunglasses here. You will also notice that everyone takes a sarong rather than a towel to the beach here – these shouldn’t cost you any more than R$25-30 on Ipanema (no matter what the guy says!).

PLACES TO VISIT

Museu do Amanhã and Museu de Arte do Rio

These two museums are opposite each other, looking over Guanabara Bay at Praça Mauá. They are both part of the Porto Maravilha regeneration project, part of the Olympic legacy, and both are fantastic! The Amanhã, or Museum of Tomorrow, is full of stimulating displays geared towards tourists, focussed on climate change. In the MAR, the first exhibit is the stunning view from the roof terrace of the museum – no artist is capable of producing anything that rivals that! However, the multi media exhibitions are a really great introduction into the culture of the marvellous city.

Museu Contemporânea de Niterói, boat to Niterói at Praça XV

The R$6, 20-minute ferry to Niterói is a no-brainer if you have time. Snobby cariocas say that the only reason to cross the bay is to get a better view of Rio, and they’re not wrong! Niemeyer’s Museum of Contemporary Art is essentially a spaceship which landed in one of the most beautiful spots on Earth; its curved windows offer a stunning view of the Sugarloaf and Centro across the bay.

0 Comments

2 Pingbacks