The city of design, which is about to be redesigned

Author: Annie Britton

Before travelling to Dundee, I solicited the opinions of a couple of friends who had studied at Abertay University and the art college. They were fairly succinct, managing to convey their feelings uniquely in four-letter words. I struggled to reconcile this anecdotal evidence, which suggests that Dundee is (to put it delicately) a bit of a dump, with my own research. Obviously, it is the job of tourism boards and other quangos to promote their city. Yes, they had some skin in the game, but I still struggled to believe that anyone was that adept at turd-polishing.

I knew there had to be something to the notion of Dundee as a creative and innovative city of distinction. I knew that there had to be something to the notion of Dundee being… not the most aesthetically pleasing urban milieu to find oneself in. When I did finally visit, I came face-to-face with both the Jekyll and the Hyde of the city. This walk is a detailed analysis of both characters.

BEST FOR…

| ‘Green Spaces’ | |

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Dudhope Park, Magdalen Green, Stobsmuir Ponds, Baxter Park, The Howff, University of Dundee Botanic Gardens |

| Natural landscapes | The Law, Balgay Hill |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | The Riverside |

| Stunning cityscape | The Law, Balgay Hill |

| ‘Architectural Inspiration’ | |

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | St Mary’s Tower, Wishart Arch, Dudhope Castle, Mains Castle, Claypotts Castle |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Verdant Works |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | HM Frigate Unicorn, Baxter Pavilion, RRS Discovery, St Paul’s Cathedral, McManus art gallery & museum, Courier Building, Malmaison Hotel |

| Modern (post-1918) | V&A Museum, Dundee Contemporary Arts, Dundee Repertory Arts, Maggie’s Centre |

| ‘Fun stuff’ | |

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Project Pie, The Auld Tram, Clarks Bakery |

| Quirky Shopping | The Cheesery, Quirky Coo, Time Lifestyle Boutique |

| Places to visit | Verdant Works, RRS Discovery, Dundee Contemporary Arts |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Dundee Women’s Festival (Mar), Dundee Beer Festival (June), Blue Skies (kite festival – Aug), Dundee Flower & Food Festival (Sep), Dundee Literary Festival (Oct), Discovery Film Festival (Oct/Nov), Dundee Jazz Festival (Oct/Nov) |

City population: 148,260 (National Records of Scotland, 2014)

Ranking: 51st largest city in UK

Date of origin: Received its charter in 1191 from King David I

‘Type’ of city: Industrial and innovative

City walkability (www.walkscore.com): 94/100 ‘Walker’s Paradise’

Some famous Dundee people: Brian Cox (actor), The View (band), Snow Patrol, The Average White Band. William McGonagall (poet), David Coupar Thomson (publisher), Lorraine Kelly (Glaswegian TV presenter who now resides in Broughty Ferry), Winston Churchill was elected as the Member of Parliament for Dundee in 1908.

Notable city architects / planners: James Thomson (town planner & architect, referred to by The Courier as ‘creator of innumerable schemes to make Dundee the City Beautiful’ – judge for yourself if he was successful!)

City status: In 1179 King William granted the earldom of Dundee to his younger brother, David; he is thought to be the ruler behind Dundee Castle, which formerly occupied the site of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Films/TV series shot here: An Englishman Abroad (early 1980s, Commercial Street, Murraygate). In 2015 the city was in talks to build a £120m film studio.

THE CONTEXT

My train stops midway across the Tay bridge and I am certain I am going to die; the expanse of the water stretches some two miles this point. Indeed, it’s a little-known fact that the Tay is the most powerful river in Britain, chucking out more water into the sea than any other. It’s a good metaphor for this city – once immensely productive and industrious, but now somewhat forgotten.

Not for much longer, though. Dundee is a city in flux, the recipient of £1 billion in redevelopment funds, as well as the first city outside of London to boast a Victoria & Albert Museum (arriving in 2018). It’s also the UK’s first UNESCO City of Design – a reference to its past, present and future as a city which looks to design and creativity to stimulate economic growth.

Beyond its trademark ‘Three Js’ (jute, jam and journalism – which will feature on our walk), Dundonians are also responsible for innovations including the electric light bulb, the postcard, aspirin and the Grand Theft Auto video game. This heritage gave rise to the “one city, many discoveries” slogan – berated by critics for its £70,000 price tag.

I sincerely hope that Dundee becomes a 21st-century success story in city branding – because it certainly has the ‘substance’, just lacking the ‘style’ which other cities (and their tourism boards) have nailed.

This walk is a fantastic opportunity to arrive before the crowds and see that redevelopment story in motion – you can always take another trip when the V&A opens.

THE WALK

As the train pulls into the station we roll slowly between the waterfront and the city, giving me a good view of the architecture: to call it a ‘mish-mash’ is probably too charitable – it’s just incongruous. Dundee wasn’t built to look pretty – it’s a city of (industrial) function. Our walk is an exploration of these functions, and the marks they left on the city: burns directed to power jute works, the factories themselves, the less-than-salubrious accommodation of the people who worked there – and the mansions the jute barons built for themselves.

couldn’t resist including this image, which really conjures up the grit of Dundee – credit

As such, we leave the station and head west to Perth Road, where most of these lovely homes still stand. There is an urban myth which suggests that when Lord Provost Alexander Riddoch built his house here in 1793 he used his position to have the entire road relocated further away from the river – just so that he could have a dry, well-lit approach to his home.

Before the Nethergate becomes Perth Road, though, we pass Dundee Contemporary Arts, a landmark collaboration between Dundee University and the city council. Opened in 1999, it is the UK’s biggest modern art space outside London, comprising two art galleries, a two-screen cinema, a print studio, and of course a café. All of this is contained within a building which repurposes old railway sheds (which themselves made use of even older structures).

As you may well have noticed, we’re still not far from the railway. Traversing the cobbled street of Roseangle, we get closer still, to where the Edinburgh-Aberdeen line runs between Magdalen Green and the Tay. From time immemorial, this is where Dundonians took their leisure, though it only dates back four centuries as an official park.

Magdalen Green in 1906 – credit

and nowadays… – credit

Its only landmark is the cast iron bandstand, built by Glasgow foundry Macfarlane’s, in 1890. The only other surviving example of this design is in Calcutta – a seemingly coincidental architectural link which ties two vastly different cities together. It is however, the remnants of a trading relationship, and rivalry, from another era. Bengal overtook Scotland as the biggest producer of jute products in the dying days of the 19th century.

Linen production was a parallel industry to jute, and its most famous fortune belonged to the illustrious and aristocratic Baxter family. Their most obvious legacy in Dundee is probably the park named after them (north east of our route), but their heir, the philanthropist Mary Ann Baxter, changed the city forever when she invested £120,000 into the creation of a new university college. Its purpose was to “promote the education of persons of both sexes and the study of Science, Literature and the Fine Arts”. Its location on Perth Road is down to the decision to purchase some Georgian villas there, which happened to be going cheap at the time (the 1880s). However, it didn’t actually gain official university status until 1967, while the second university, Abertay, was enshrined in 1994.

It quickly made its mark, though, launching the world’s first computer gaming degree in 1997. Months later, the world was first introduced to the macabre and violent world of the Grand Theft Auto video game, which, for reasons I will never understand, lots of people really like. The series has, to date, generated almost a quarter of a billion dollars in sales.

On a slightly smaller scale, the nearby Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art (one of the UK’s best art colleges) has had a hand in engendering an atmosphere of creativity in Dundee. Firstly, it is the lifeblood which keeps DCA going as an arts centre for visitors and locals alike. But secondly, the consistent output of artists and creatives in Dundee, many of which are affiliated with the college, has made Dundee a creative hub whose reputation precedes it, and which garners the kind of recognition which made it the choice location for the forthcoming Victoria & Albert design museum.

The universities are, as such, the source of the creative energy which has powered the city’s redevelopment and which will generate so much more opportunity for their fellow citizens. Though those Georgian villas now house students rather than jute barons, they’re still home to the city’s entrepreneurial spirit.

Our next stop is the spiritual home of the jute economy, where the city’s industrious nature first cultivated the city’s wealth: Verdant Works, the jute museum. The former factory’s descriptive name is a reference to the green rolling fields which once occupied this space; the Scouring Burn which flowed through them was used to power the machinery and so several works sprang up, the pastoral landscape giving way in the 18th and 19th centuries to an industrial quarter. Between the works themselves, a thriving tenement community sprang up, though it was town down in 1960s slum clearance programmes.

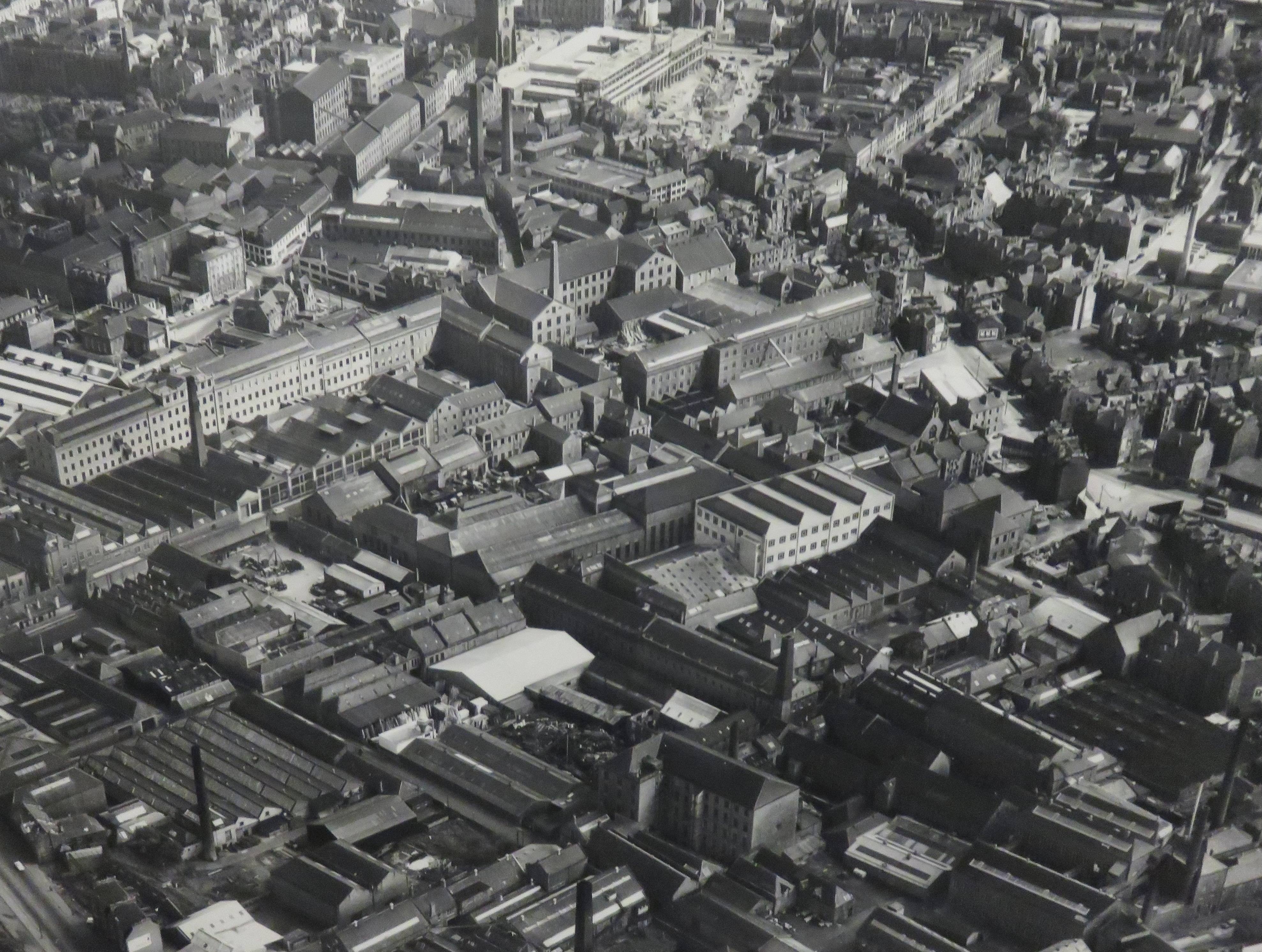

Blackness from above, Verdant Works in the centre (photo of a display at the museum)

So, beyond business acumen, what were the ingredients that created this industry? Well, much of the city’s workforce was already trained in the manufacture of flax and rough linen, but when a subsidy on linen was lifted, other fibres became more attractive as a business proposition. A successful whaling industry was already operating from the harbour, generating a by-product of whale oil which some clever fellow discovered could be used to soften jute until it could be processed in the same way as linen. The existing shipping tradition based around the whaling industry was applied to the import of raw jute from Bengal – in fact, the East India Company had been looking for new export markets for their raw jute, and Dundee came along at an opportune moment. The supply side taken care of, demand was furnished by an increasing demand for jute sacks to transport goods around the growing empire.

This is how Dundee earned the moniker “juteopolis” for the duration of the Industrial Revolution (eventually ceding it to Calcutta). However, as with many cities which flourished in this period, it was victim to the unholy trinity of unbridled immigration causing overcrowding, zero urban planning, and deprivation stemming from huge income disparity.

Lord Cockburn (1799-1854) vilified the city as “the sink of atrocity which no amount of moral flushing can cleanse” – however, it should be noted that he had travelled to Dundee to research crime, so he was very much looking for its grotty underbelly.

Inequality created a situation whereby, by the start of the 20th century (when Dundee lost its competitive edge), wages here were the lowest in Scotland – but the cost of living was the highest. In 1911 three quarters of the population lived at least two-to-a-room (the London equivalent was just 32%). Overcrowding allowed cholera, typhus and smallpox to thrive, and when the war broke out a few years later, 50% of Dundonian army volunteers were turned down because of their poor health. This sector of the population, though sizeable, had such little purchasing power that there was little incentive for investment in the city, and the decline intensified.

Some argue that the jute industry’s decline was well-handled, owing to a consensus between unions, employers and the city. New employers such as NCR (manufacturers of cash machines) and Timex kept unemployment at bay until the Seventies. The scapegoat for Dundee’s latter deprivation woes is Thatcher, and her government’s rescinding of state support for industry.

Distinguished journalist James Cameron was perhaps ahead of his time when he called Dundee “a symbol of a society that had gone sour” in the Thirties. It has been, for quite some time, and particularly in Scotland, fashionable to excoriate Dundee as an urban embodiment of grimness.

Nowadays, an old mill opposite Verdant Works hosts studios run by WASPS, a charity providing affordable space to artists and arts organisations – an example of the socially-conscious spirit which thrives all around Scotland. If only it had done so during the jute era!

From here, we ascend towards the Law, once again passing through residential areas. The first residence we pass is certainly the grandest on our walk: Dudhope Castle. Its original incarnation dates back to the 13th century, but the current structure was built in 1460 and extended in 1580, to an L-plan structure (a shape often used to facilitate the castle’s defence). Its military history is fairly extensive, having been a home to warring aristocrats and more humble soldiers at many different points in history. Latterly, it was used as a barracks in both world wars. Horrendously, the corporation of Dundee had intended to demolish the castle in 1958 but their plans were thwarted and it is now used as offices and buildings for Abertay University.

Dudhope Castle set in the gentle slopes of the park – credit

The park itself was of course the castle’s gardens, purchased by the corporation for public enjoyment in 1895. The steeply sloping nature of the park prevents it from being landscaped into anything terribly exciting, but the views make it an obvious place for a picnic on a fair day. Dundonians do, however, get the use of a playground, basketball court, tennis courts and a skate park. Can’t imagine what else you’d really need in the way of leisure!

Continuing up to the summit of the Law, the views get better as your legs get wearier. As someone who grew up in the Fens, my default expectation of a new place is that it will be flat. Dundee took me quite by surprise! I’d really earnt my lunch by the time I finished this walk, and so will you.

This is what the weather really looked like when I visited! The view from the Law

The law (Scots for ‘hill’) is a volcanic plug, which is a good 400 million years old. To put it into context – as far as that is possible – the Law came into being before the supercontinent Pangaea had even formed. Once humans started kicking about (that’s only 200,000 years ago, by the way, and god only knows how long it took them to get from sub-saharan Africa to Angus), they used the Law for defence, turning it into an Iron Age hillfort. Graves from approximately 1500 BC and Roman pottery from the 1st century AD have been found here by archaeologists. In terms of the lifetime of this hill, that seems like yesterday…!

In the 1820s a tunnel was built through the Law to facilitate the new Dundee to Newtyle railway. It was subsequently closed, in the Eighties, but in 2014 a campaign was launched to reopen it as a tourist attraction… maybe in the second edition of Urban Rambles we’ll be able to tell you more!

On the descent, you’ll notice the route takes a nonsensical turn round two crescents off Constitution Road. Obviously, the deviation isn’t obligatory, I just thought it would be nice to point out these lovely early-Victorian villas by David MacKenzie, originally laid out as “Chapelshade Gardens”. The name presumably arises because as the sun would set in the West, St Mary Magdalene’s Episcopal Church would cast a shadow over this part of the street. The Church itself can be seen just below Dudhope Street, on Constitution Road – worth a look, it is a very impressive example of gothic revival architecture.

Going west on Dudhope Street, the architecture soon changes from such impressive villas and tenements to council flats, just before you cross Hilltown, an area of industrial accommodation which has really suffered the effects of industrial decline. This is why we are skirting past it…!

A romantic photo of Hilltown which bears no resemblance to its present reality – credit

From here onwards, we re-enter the city centre proper, beginning at The Cowgate Port, which marked the Eastern extremity of Dundee in Medieval times (it stretched westwards less than a kilometre). The city walls were erected owing to a period called the “rough wooing”, a conflict between Scotland and England which arose when the latter tried to break the Auld Alliance. The Cowgate Port is the last surviving piece of the defences, and one of only two surviving burgh gates in Scotland. It survived General Monck’s 1651 sacking of Dundee because of its association with George Wishart, who used it as a pulpit to preach to plague victims a century earlier. Hence its alternative name, Wishart Arch.

From here we head right into the centre of town on Seagate, one of the oldest parts of the city, dating back to the 11th century; it was formerly used as a market before the city developed westwards. However, a lot of the original structures here were destroyed in 1906 by a fire in a spirits factory, which was said to have sent “rivers of burning whisky” through the city.

We turn up Commercial Street, so named because it leads us to the focal point of Dundee’s trading community, the Royal Exchange. It was built in 1850 by the Baltic Merchants, and so its architect, David Bryce, chose an elaborate design based on Dutch cloth halls. Unfortunately, the ground was waterlogged and its foundations began to slip, only becoming stable when the building’s crown steeple was removed. On the side, you can still see parts of the building which tilt at an angle as steep as the Tower of Pisa.

Continuing round Panmure Street, we see the impressive High School of Dundee. Originally founded in 1239, its current building is a Victorian amalgamation of the old Grammar School and the Academy. The Doric-columned portico makes the school look like a real “temple of learning”. The school is currently engaged in “the biggest capital campaign ever embarked on by an independent school in the UK”, to transform the red sandstone former post office, across the road in Euclid Crescent, into a groundbreaking new arts centre. Add that to the list of expensive but exciting arts investments, then.

Indeed, the McManus Galleries at the centre of Panmure Street were the original “big shiny arts centre” in Dundee. It was commissioned a few years after the death of Prince Albert in 1861, the largest memorial dedicated to him outside London. Its original purpose was to be a “working man’s free reading room”, but as a gallery and museum nowadays, it has a collection representing several areas of Dundee’s history. In a way, one of the biggest works of art here is the building itself. Yet another remnant of the Gothic Revival, although its architect Sir George Gilbert Scott actually claimed to have invented his very own architectural style with its design…!

The fairytale-worthy Galleries

Continuing through the Meadows area, we come to the Howff, the last of our green spaces, and indeed the only one within Dundee’s Medieval centre (which would have been the extent of the city when the Howff was established in 1564). Previously, it had been land attached to the Franciscan Monastery. Following the Scottish Reformation, Mary, Queen of Scots dedicated the land to the people of Dundee, for the same purpose. However, so few of its citizens could afford headstones, and it degenerated into a small grassy expanse. Its de facto purposes were the grazing of livestock and the drying of laundry, and it took on a sort of village green role. Its name comes from this secondary use: ‘howff’ is Scots for ‘meeting place’.

The Howff with the Courier Building in the background – credit

On the top edge of the Howff, you will have passed the Courier building, the headquarters of DC Thomson, which publishes, among others, Dundee’s newspaper and the Beano and Dandy. This company alone constitutes another of the three ‘J’s – journalism – indeed the only one remaining in the city as a large employer. The building is one of the most interesting pieces of architectural history in the city: built in at the start of the last century in true American style, it was the first construction in Scotland to make use of the innovative Hennebique concrete system – in order to avoid the slippage that had occurred with the Royal Exchange. It was extended in 1960, with a proto-skyscraper continuing the American theme. Above the doorway are sculptures of Literature and Justice, by Glaswegian artists Albert Hemstock Hodge.

As you cross the high street next to City Square, you will walk past the much less serious statues of Minnie the Minx and Desperate Dan, from the Beano and the Dandy. The Square is home to Dundee’s principal cultural venue (though, as you may have noticed, there really are a lot of them): Caird Hall. It bears the name of its benefactor, James Caird, who – surprise, surprise – was a jute baron. Its 1914-23 construction (delayed owing to the war) necessitated the demolition of the Vault (“an overcrowded warren of closes and tenements”) and the Greenmarket. The venue has hosted acts from The Beatles to Frank Sinatra.

the infamous statues – credit

The impressive City Square from above, the pillars of Caird Hall to the right – credit

Our route back to the waterside takes us along Whitehall Crescent, which stretches round the oval-shaped building now housing the Malmaison Hotel. Its original occupier was the Mathers hotel, built in 1860 as a ‘temperance hotel’ by Margaret Mathers. Imagine checking into a hotel for a nice wee stay by the seaside and not being able to have a pint! Needless to say, a hotel with such an ethos didn’t do too well commercially, and by the late 20th century it had been earmarked for demolition. Its reopening by the Malmaison chain was a coup for the waterfront development, a cornerstone in attracting investment and tourism to the city. Maybe one to consider if this ramble is going to be part of a weekend away!

At present, the next fifty feet of the walk will take you past a great big building site – this is of course the much-lauded waterfront development area. I truly can’t wait to revise this chapter in a few years’ time when it’s all built and looking lovely! For now, we can only ruminate on what it might look like – and look at its history. Dundee has long been an important trading post, but it became evident during the Victorian era that its harbour wasn’t quite up to scratch, at least for the sizeable vessels which were used in the heyday of the Industrial Revolution – they were going all the way to Calcutta, after all. Over the 19th century, five more docks were built, and the city became increasingly separated from the waterfront. Later on, architect James Thomson (the “creator of innumerable schemes to make Dundee the City Beautiful”) proposed a civic centre on the waterfront, but his plans were shelved, owing to the wars which punctuated the period. More than a century later, Dundee will get its civic centre, in the form of the V&A, intended to be a “living room for the city”, focussed on design – a theme the city epitomises. The city and the waterfront will be linked once more, via a “high-quality, mixed-use riverside urban quarter” which will “signify Dundee’s renaissance as a post-Industrial city”. This last phrase is telling, because I think Dundee is one of Britain’s last industrial cities whose renaissance we can still witness. That is to say, there isn’t yet a slew of cafés serving avocado toast in the city, so the propitious rambler may arrive before the gentrification begins and the hordes of tourists descend! Maybe I’m being a bit optimistic about the V&A’s effect, but one imagines this is pretty much what the council is hoping for… Of course, it’s not that simple – landing a big flagship cultural centre does not always precipitate the cultural renaissance which it is meant to herald. DCA director Clive Gillman calls this – wonderfully – “irritable Bilbao syndrome”, referring to that city’s Guggenheim, which it discovered was not a silver bullet for the city’s growth as a tourism destination. Gillman states that the challenge is “how to make a massive institution like the V&A work within the context of a local strategy. That’s the really exciting thing. But that’s not easy either.” Very true Clive, I would suggest that if it gets too challenging maybe you should just quit and write puns for a living.

At this point in the walk, you’re probably thinking to yourself that you’re on the home straight, and I still haven’t explained the third ‘J’. No? You weren’t? You were more concerned with the fact that it’s nearly time for lunch? Well, I’m going to tell you anyway. The third ‘J’ stands for jam – although, confusingly, it really refers to marmalade. My mother’s very favourite breakfast spread was invented here, the result of some experimentation with a dodgy consignment of oranges which had arrived in the harbour. The first brand to bring it to market was Keiller & Sons – though this was a bit of a misnomer, since it was James Keiller’s wife Janet who actually made the first batch, and who after her husband’s death ran the company with aplomb.

The very last stop on our walk is Discovery Point, where the Royal Research ship Discovering is berthed. It was built here in 1900-1, its mission being to transport the ill-fated Scott expedition to the South Pole – Antarctica then being an uncharted wilderness. The city was chosen for its construction, as the city’s shipbuilders had amassed an expertise in cold-water vessels during the preceding century, when whaling was important as a supporting industry for jute. The ship itself is a wonderful visitor attraction, but I found that its decks were really the best place in the city to look out westwards towards the bridge and watch the sunset over the Tay, and reflect on another brilliant urban ramble.

WALK DATA

Distance: 8 kms (5 miles)

Height Gain: 194m

Typical time: 2 hours

OS Map: Ordnance Survey Explorer Map 380 Dundee & Sidlaw Hills

Start & Finish: Dundee train station, South Union Street, DD1 4BY

Terrain: All on tarmac but a steep ascent up the Law

THE ROUTE

- Come out of the station to your right, towards the RRS Discovery. After a few hundred yards, head left towards town on Riverside Drive, and then bear left again onto the A991, following it round past the illustrious Mecca bingo hall.

- Turn left onto Nethergate, heading Westwards and parallel to the estuary (behind you). Follow the Nethergate, which becomes Perth Road, for about 500m before turning left onto Roseangle, which slopes down towards the Tay and Magdalen Green.

- Once you reach the park, you may wish to walk through it, or traverse its northern edge on Magdalen Yard Road. You will then turn back away from the river, up Shepherd’s Loan, and back onto Perth Road.

- Head back East on Perth Road until you reach the Dundee School of Architecture (opposite Drouthys). Here you will jut up on Hawkhill Place and weave through the campus onto Old Hawkhill, and then continue due north until you reach a large roundabout where Hunter Street meets Hawkhill.

- Go straight over the roundabout onto Horsewater Wynd, reaching Guthrie Street in less than a hundred yards. A few metres to the left, and then due north again onto West Henderson Wynd (following signs in this area towards Verdant Works will help).

- From this point, it is due north, and uphill, for almost a kilometre (up the Law). You will cross Douglas Street, Lochee Road, Dudhope Park, Dudhope Terrace and Albany Terrace. From this point onwards, you will climb stairs, crossing Adelaide Place and Kinghorne Road, before reaching the summit.

- Descend down Law Road, bearing left at the junction onto Kinghorne Road. Shortly after, you will take another left onto Upper Constitution Street which leads you all the way back down to the city centre.

- Just before you reach the very bottom, take a left onto Dudhope Street. At the end of the road, keep going on the path, crossing Hilltown onto residential Eadie’s Road – the path continues. 100m later, you will finally jut down again, crossing Victoria Road onto Ladywell Avenue. This eventually curves round into St Roque’s Lane, bringing you to the Wishart Arch on Cowgate.

- From Cowgate, take the path parallel to East Marketgait (the busy main road), crossing underneath it, and then back onto Cowgate. It’s effectively a different street now by the same name, owing to its bisection by the dual carriageway). Turn left onto the very narrow Sugarhouse Wynd, and then right onto Seagate, staying on it for roughly 300m, all the way into town.

- You will eventually find a red pub on your right hand side called Tickety Boo’s. Here, turn right onto Commercial Street and follow it up to Albert Square. Walk all the way round McManus Galleries, Panmure Street forming a kind of arc behind it, and back onto Meadowside. Head due west along the northern edge of the Howff (the cemetery will be to your left).

- You may choose to walk through the Howff, or round three of its edges and back onto Reform Street. You are now heading due south, towards the Tay.

- At the bottom of Reform Street you will face Caird Hall (the statue of Desperate Dan is just to your left, in front of H. Samuel). Bear to your right along the cobbled high street, and then turn left onto Crichton Street, once again heading directly towards the Tay.

- Just before reaching the waterfront development area/building site again, follow Whitehall Crescent round to your left, past the Malmaison Hotel. From here, retrace your first steps back past Discovery Point to the station.

PIT STOPS

Project Pie (48-54 Reform Street, DD1 1RT, +441382 220909) American chain Project Pie shunned London and instead chose humble Dundee for its very first UK location. The concept is build-your-own artisanal pizza – good fun with kids in tow.

The Auld Tram (54 Commercial Street, DD1 2AT, +44 7938 318986) This old railway carriage, built in the 1870s sits proudly in the middle of Dundee’s city centre, serving very standard fare (i.e. sandwiches in flavours which existed before Millenials were born).

Clarks Bakery (Unit 3, Annfield Road, DD1 5JH, +44 1382 641048) Clarks is a Dundee institution: a beloved bakery open 24/7 – there is even occasionally entertainment in the wee hours (whether organised or just in the form of a fight).

QUIRKY SHOPPING

The Cheesery (9 Exchange St, DD1 3DJ, +441382 202160) I’m just a sucker for anything edible! The Cheesery has a decent range of both Scottish cheese and varieties from further afield, rotating on a regular basis.

Dundee Contemporary Arts Shop (152 Nethergate, DD1 4DY, +441382 909 900) This really well curated gift shop has all of the usuals – jewellery, design, craft – by Scottish artists and from others in the UK, too. Special focus is given to art produced at DCA, though, including in their dedicated print studio.

PLACES TO VISIT

Verdant Works (West Henderson’s Wynd, DD1 5BT, +441382 309060) Named after the green fields the jute mill was built on in 1833, the Works is now a museum of the industry it was once part of. It’s informative and interactive, but the real bonus of this museum is that the original machines and buildings really give you a feel for the industry which defined this city.

RRS Discovery (Discovery Point, Discovery Quay, DD1 4XA, +441382 309060) It’s nothing short of wonderful to be able to board the ship which took Captain Scott to Antarctica! The vessel now plays host to what is a pretty standard recreation of the conditions the sailors lived in, but what sets it apart are the views of the Tay estuary.

Dundee Contemporary Arts (152 Nethergate, DD1 4DY, +441382 909 900) With two galleries, a two-screen cinema, a print studio and a lovely little cafe, DCA has a lot to offer the contemporary art lover. One of the UK’s leading art colleges is in Dundee (Duncan of Jordanstone), so there is more than enough talent to keep it filled to the rafters with exciting art.

Leave a Reply