Regal and raucous in equal measure

Author: Annabel Britton

Edinburgh’s cup runneth over with architectural history. The Old Town’s at-close-quarters conviviality is credited with having helped to stimulate the Scottish Enlightenment. The Georgian New Town rivals Haussman’s renovation of Paris – in fact Robert Louis Stevenson called his birthplace the “envy of Paris” and there is many a proud Edinburger who would do the same now. Edinburgh also owes its immense popularity with natives and visitors alike to the abundance and diversity of green spaces: our route takes us up and over dormant volcanoes, through drained lochs (now public parks), along a river, round city squares and the Botanical Gardens, even through disused railway tunnels. At the Gallery of Modern Art, you will walk across Charles Jencks’ Landform: a piece of art beneath your vgery feet – but then, much of Edinburgh may feel that way.

BEST FOR

‘Green spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Holyrood Park, The Meadows/Bruntsfield Links, St Andrew’s Square, Princes Street Gardens, George Square, Botanical Gardens, Victoria Park, Leith Links, King George V Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Water of Leith, Hermitage of Braid, Union Canal |

| Stunning cityscape | Views from Arthur’s Seat, Calton Hill, roof of National Museum, Scott Monument, Castlehill, North Bridge |

| ‘Architectural Inspiration’ | |

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1740) | St Margaret’s Chapel in Edinburgh Castle, parts of St Giles Cathedral, parts of Holyrood House, parts of the Royal Mile, Canongate, Tron and Greyfriars churches |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | The New Town, Old College |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | The suburbs of Newington, Marchmont and Bruntsfield |

| Industrial Heritage | Forth Rail Bridge, Union Canal, The Shore |

| Modern (post-1918) | Scottish Parliament, National Museum of Scotland |

| ‘Fun stuff’ | |

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Summerhall, The Dogs, Chez Jules, Peter’s Yard, Ensign Ewart, Panda & Sons, Café at Gallery of Modern Art, Teviot Row House |

| Quirky Shopping | Stockbridge, Farmers Markets, Century General Store |

| Places to visit | Edinburgh Castle, Scottish Parliament, Palace of Holyrood House, National Museum, National Galleries, Royal Yacht Britannia |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Edinburgh Festivals, Christmas Market, Sammhuin and Beltane Fire Festivals |

City population: 490, 000 (National Records of Scotland, 2014)

Urban population: 835, 000 (Eurostat, 2015)

Ranking: 14th largest city in UK

Date of origin: 2nd century AD

‘Type’ of city: Varied! Historical, cultural, architectural.

City walkability: (www.walkscore.com): 93/100, ‘Walker’s Paradise’

City status: One of the first Royal Burghs created by King David I in 1153. In Scotland there is no correlation between city status and having a cathedral; Edinburgh was granted city status in 1889 despite St Giles Cathedral having been the city’s religious focal point for some 800 years previous.

Some famous Edinburgh people: JM Barrie (author), Arthur Conan Doyle (author), JK Rowling (author), The Proclaimers (band), Ian Rankin (author), Bay City Rollers (band), Sean Connery (actor), Ronnie Corbett (comedian), Kirsty Gallacher (television presenter), We Were Promised Jetpacks (band), Nicky Campbell (television presenter), Alexander Graham Bell (inventor of the telephone), Alexander McCall Smith (author), Muriel Spark (author), Irvine Welsh (author), Robert Louis Stevenson (author), David Hume (philosopher), Chris Hoy (cyclist), Tony Blair (politician), Mary, Queen of Scots, Greyfriars Bobby (dog!)

Notable city architects / planners: William Henry Playfair, James Craig, Robert Adam, Enric Miralles

Films/TV series shot here: Trainspotting (1996, Princes Street), One Day (2011, Old College, Stockbridge and Arthur’s Seat), Filth (2013, Victoria Street among others), Sunshine on Leith (2013, Princes Street Gardens and Waverley Station), Rebus (TV Series)

CONTEXT

It seems that Edinburgh has always been populated by an innovative bunch: geographical landmarks which could have been a hindrance, like dormant volcanoes, stagnant lochs and the limiting Firth of Forth have been transformed, one by one, into assets of commerce and culture.

Archaeologists do not know decisively when settlers first seized upon Castle Rock’s obvious defensive advantages, but ever since the city has been emanating outwards. First, down the Royal Mile, the ‘tail’ to the crag of Castle Rock, then building tofts perpendicular to the main thoroughfare – strips of land allocated to merchants, upon which they were obligated to build a house within a year and a day. This grew into the Old Town, the medieval quarter which typifies organic, unplanned urban growth. The streets are quite literally on top of each other, and buildings are so tall and crammed in that the light becomes somewhat sparse – no wonder its inhabitants once suffered from vitamin D deficiency!

For exactly such reasons, the Nor’ Loch (which had hitherto prevented expansion north of the High Street) was drained in the 1810s. It had become a polluted cesspit – detritus and sewage was thrown down the hillside – and it’s said the gases rising from the stagnant mere caused people living in nearby closes to succumb to madness. It was also the site of smuggling, witch-duckings and suicide. Its removal and the subsequent creation of the New Town heralded Edinburgh’s entry into urban modernity.

Designed according to the grid popularised again by the Renaissance, James Craig’s plan is comprised of three central avenues, bookended by civic squares. Cutting across them are perpendicular streets, following the contours – George Street runs along a ridge, with Princes and Queen Streets laying either side.

Once it had overcome this initial obstacle, Edinburgh’s sprawl continued northwards like a tidal wave, subsuming existing villages on the way (charming Stockbridge, Dean Village and Newhaven amongst them) until it reached the sea. The only one which claims to have retained its sovereignty is Leith – its inhabitants voted 5:1 against merging with Edinburgh in 1920. They were ignored – symptomatic of how Leithers may have often felt during the late 20th century, when the burgh suffered from deindustrialisation and its social consequences. Regeneration, particularly of the Shore area, has boosted its image no end, and it has now become the epicentre of Edinburgh’s sizeable creative community (though cries of gentrification are becoming more and more audible).

This is Edinburgh’s 21st century challenge: how does it move forward when history is the city’s USP? There is a sense that the city got its fingers burnt with the first regeneration of Leith Street and the wish to avoid repeating this catastrophe has morphed into a reticence to do anything at all. Local architect Gareth Hoskins has called for the city to be “as confident with what we’re doing now” as his forerunners were when they were building what he calls “big, brave pieces of architecture” like the National Gallery and Royal High School. Hopefully, the city will shake off this stasis and embrace the new as much as it does the old; as Hoskins says, “cities work because different elements have come together and melded into a city” and Edinburgh is a shining example of that. Long may it continue to be.

WALK

We begin at the Scottish Parliament building, opposite the Palace of Holyrood House; two symbols of Nationalism and Unionism standing as if in some kind of face-off. Such politics in Scotland are a quagmire, so let us instead pass to the architecture and history.

A Catalan architect named Enric Miralles won the 1998 competition to design Scotland’s new parliament building. Intriguing though it is that an architect from another province seeking independence was chosen, this was mostly down to public opinion on the entrants’ proposals. The symbolism of the building is manifold; free tours of the Parliament can be booked online and are highly recommended.

Holyrood House across the road is a much more ancient beast: an abbey was founded on its grounds in 1128 and it has been in use as a royal residence for some 700 years. It has seen just as much brutal political manoeuvring as its neighbour, though: Mary, Queen of Scots’ secretary David Rizzio was stabbed 56 times in the Queen’s privy chamber, before her very eyes while she was six months pregnant – he was allegedly the father.

Up onto Salisbury Crags, whose very age trivialises such matters. Like Arthur’s Seat and Castlehill, it is the remains of volcanoes dating back to the Carboniferous era (roughly 350 million years ago), when Scotland lay near the Equator. Indeed, Edinburgh is the only city in the world with a volcano within the city limits.

The Crags were the scene of major breakthroughs by James Hutton, the father of geology. You will walk over “Hutton’s Section”, where he gathered evidence for his work Theory of the Earth, in which he explained how sedimentary rock was composed on the seabed and raised to its current level over time.

Thrilling stuff! Back into the city, through the Victorian suburb of Newington. The district’s main attraction is Summerhall, the former veterinary college of Edinburgh University but now an innovative arts venue. Crucially, it also houses a pub (the old students’ union).

If you don’t stop off for a pint or further cultural stimulation, you’ll cut through onto Sciennes (“sheens”), now lined with halls of residence. In the past the area was known to attract “vagabonds, vagrants and outlaws”; my experience there as a student was comparable. A concern for the spiritual welfare of its populace led to the establishment of a convent named after Catherine of Siena. French being the court language at the time (the 16th century), “Siena” became “Sienne” which became “Sciennes”. It is one of a multitude of street names in the city which visitors never know how to pronounce, Cockburn Street being undoubtedly the funniest.

Half a mile down Sciennes Road and we find ourselves in Marchmont, where each street is lined with stunning Victorian tenements. Alcohol was originally banned here, and by way of some kind of hangover (if you’ll forgive the pun), there are still only two pubs here. Amazing then, that so many of the city’s students have decided to make it their home. Its more famous residents include Ian Rankin’s Inspector Rebus and Muriel Spark’s Miss Jean Brodie.

At the bottom of Marchmont Road we cross over onto The Meadows. Originally a marshland called the South Loch, it supplied much of the city’s drinking water until the early 17th century, before being drained in the 18th century. Later it became an important place in the development of the city’s football teams, with the first local derby, Hearts versus Hibs, being played here on Christmas Day 1875. On a fine day, it is still a very sporting park, with everything from tennis to Frisbee being played between the tree-lined paths which criss-cross it.

Towering up above the trees is David Hume Tower, obscuring the view of Arthur’s Seat in a most egregious manner. The Enlightenment philosopher once said “beauty is no quality in things themselves” and I think its designers probably took that quotation too literally when conjuring up this structure, which is none too popular with students. Appleton Tower and the University Library are the other components of the 1960s redevelopment which ravaged the hitherto completeness of George Square, which many decried as an act of cultural vandalism. Fortunately, Edinburgh is not short of Georgian architecture!

Above, in Bristo Square (on the right of Middle Meadow Walk as it rises up northwards), is another university building – one which I certainly prefer spending time in. Teviot Row House is the oldest student union in the world and bears a slight resemblance to Hogwarts with its gothic turrets. Continuing north you will walk past Bedlam, now the university theatre but so-named because it is housed by the city’s former asylum, adjoined to the old workhouse which is now the rather more luxurious Hotel du Vin.

Opposite is Greyfriar’s Bobby, the infamous pup who supposedly stood by his owner’s grave in adjacent Greyfriars Kirkyard for 14 years after his death. The other sight that draws the tourists to this corner is the Elephant House Café, where JK Rowling first began Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. The fabulous and free National Museum of Scotland is just across the road; even if you don’t have time to look round, nip in and take the lift up to the roof to catch yet another brilliant view of the city.

We descend now into the deep, dark Old Town. More specifically, into the Grassmarket, the site of executions in days gone by, though its population is generally more legless than headless these days! One of the pubs on the right-hand side is named after Maggie Dickson, a Musselburgh fishwife who has hanged in 1724, convicted of having murdered her newborn baby. She supposedly awoke on the way back to Musselburgh, and since her punishment had already been carried out, she was allowed to go free. Her legend lives on even longer than “half hangit’ Maggie herself…

Edinburgh’s affectionate nickname, ‘Auld Reekie’ (‘Old Smoky’ in Scots) stems from the smoke seen rising over the tenements of the Old Town. Robert Chambers, Victorian publisher, ascribed the coining of this name to Fife laird Durham of Largo who used the rising plumes to police his children’s bedtimes.

It is evident from the overlapping streets and towering tenements that the Old Town became very over-crowded. Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe wrote: “… though many cities have more people in them, yet, I believe, this may be said with truth, that in no city in the world [do] so many people live in so little room as at Edinburgh”. This close proximity was necessitated by the fact that the Nor’ Loch just above the High Street prevented expansion northwards (more of which later).

Though this over-population probably provoked ill health in many citizens, it also generated an atmosphere of much interaction between the different social classes. Each tenement block was a cross-section of society, with which storey a person lived on denoting their status: the poorest of labourers in the cellar, their superiors in the attic, shop-keepers and such just below while the middle floors would be occupied by nobles, judges, doctors and such. Some historians have pointed to this conviviality as a factor in stimulating the Scottish Enlightenment, one saying “a man of inquiring mind could not live in old Edinburgh without becoming a sociologist of sorts”. This was one of the causes of opposition to the New Town development: in solving the city’s over-crowding problem it would also tear apart its social fabric. But our walk isn’t quite there yet…

First, up to the castle. Castle rock has been occupied since the Iron Age (2nd century AD), though the oldest standing building there (and the oldest building in Edinburgh) is St Margaret’s Chapel, from the early 12th century. It lays claim to being “the most besieged place in Great Britain and one of the most attacked places in the world” – it was even bombed by German zeppelins in 1916.

Unsurprisingly, Edinburgh derives its name from the city’s focal point: Din Eidyn is Castle rock’s name as it first appeared in medieval Welsh poem Y Gododdin (anon. C7th-11th disputed), a eulogy for Welsh warriors who died in battle after having spent a year ruling over Edinburgh from their hill fort. The “burgh” was added later when King David I granted it royal burgh status in 1153.

We walk down into Ramsay Garden, with its distinctive red and white cladding – strange colours to have chosen for a development so close to one of Scotland’s most famous sights! Past the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland where Mrs Thatcher gave her infamous “Sermon on the Mound” and down the Playfair Steps, named after William Henry Playfair, architect of many New Town landmarks including the Scottish National Gallery, on our left.

We have just crossed what used to be the Nor’ Loch, drained at the beginning of the 19th century. The next section of our walk takes us through the Georgian New Town, built so that the moneyed classes could escape the unsanitary conditions of old Edinburgh – in fact some already had, to London, and the city’s officials wanted to stop this flight of wealthier citizens.

In January 1766 a competition was held for the design of the New Town, won by James Craig (who at the time was just 26); he would go on to have immeasurable influence on the city. An original plan was for a central circus emitting vertical, horizontal and diagonal streets, mimicking the ‘Union Jack’ – demonstrating the civic patriotism which proliferated in this era. Eventually this plan was cast aside in favour of a simpler grid, following the contours of the land and a somewhat more subtle homage to the Union.

The main thoroughfare was named after the reigning monarch, King George III. The gardens at either end of it were to be called St Andrew’s Square and St George’s Square, after the patron saints of Scotland and England but the latter was changed to Charlotte Square (after the Queen) to avoid confusion with George Square in the South Side. Queen Street was also named after the King’s wife, Princes Street after their two sons, Hanover Street after the ruling dynasty, and Frederick Street after the King’s father. Continuing the theme were Thistle and Rose streets, references to Scotland and England’s national emblems.

Walking westwards along George Street, we end up in Charlotte Square. On its Northern edge is Robert Adam’s masterpiece of urban architecture, the National Trust property simply named “Georgian House” – well worth a visit. Just next door is Bute House, the First Minister of Scotland’s official residence.

Walking down Belford Road, we get a good view down into Dean Village. At the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, we step down onto the Water of Leith and through the village itself. Taking advantage of its position on the fast-flowing stream, it became an industrial centre based on milling. However, with the construction of the Dean Bridge overhead in 1831, it lost its passing trade and became the quiet little backwater that it is today. Enjoy the peace!

Passage under St Bernard’s Bridge signals our entrance into Stockbridge, another village which was subsumed into the city, in the 19th century. It is famed for its bohemian ambience and artistic heritage: numerous musicians, writers and thespians have made this distinctive quarter their home, including Irish comedian and actor Dylan Moran, Garbage singer Shirley Manson and Warhol muse Nico.

One of Stockbridge’s most intriguing characters is Madame Doubtfire. Children’s writer Anne Fine, also a Stockbridge resident, modelled her famous protagonist on Annabella Coutts, nicknamed Madame Doubtfire after her rag and bone shop on North East Circus Place. In the early 70s, as Anne Fine was adjusting to life in Edinburgh (having recently moved there), a very young Robin Williams was just getting his start as a comic actor in a performance of The Taming of the Shrew at the Edinburgh Festival. Who could have dreamt that 20 years later his portrayal of her character would bring such infamy to the proprietor of a Stockbridge bric-a-brac shop?

As we walk down Arboretum Avenue we skirt the Western end of the Stockbridge colonies, eleven parallel streets built between 1861 and 1911 to provide affordable accommodation for artisans. Nowadays they are not so reasonable – over £200, 000 will only buy you a one bedroom flat here.

We enter the Botanical Gardens at the West Gate and proceed, somewhat indirectly, to the East Gate. Founded in the 17th century, the outside section boasts numerous gardens of varying themes, but I heartily recommend paying the small donation to look inside the glasshouses – a tour through our planet’s temperate, tropical and arid environments is often welcome on a cold and blustery Edinburgh day.

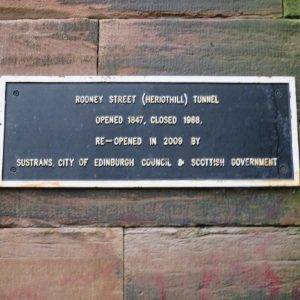

From here, we cross Inverleith Row and eventually make our way onto a real hidden Edinburgh gem: the disused railway tracks. In the opposite direction, you can walk to early 20th century Victoria Park and the redeveloped Shore, where in the pub of the same name you can listen to some lovely jazz most evenings. However, we embark northwards, through the Rodney Street tunnel and into King George V Park, where there is a small playground. It is also the site of the Scotland Street Tunnel which was the city’s biggest and safest air raid shelter during the Blitz.

Climbing up out of the shaded park there is a definite sensation of having been underground; now we find ourselves once again in the splendour of the New Town. Walking up Scotland Street, round Drummond Place, up Dublin Street we eventually find ourselves opposite the imposing red sandstone National Portrait Gallery. It was the world’s first purpose-built portrait gallery, intended as a shrine to those who shaped Scotland’s history. Nowadays, it hosts thousands of works and tours with names like “Fur Coat an’ Nae Knickers” and “The Best Wee Nation & the World”. Worth a visit, then.

We proceed down York Place to the Arthur Conan Doyle pub, so-named because the great man was born just across the road at 11 Picardy Place. The area looks utterly different to how it would have done in his time; in the mid-60s it fell victim to a thirst for redevelopment, in much the same way that George Square did. The St James Quarter – hardly in keeping with the rest of the picturesque city – will now be revamped again, touting itself as a high-end shopping destination. Which is, um, what it was before.

The very final strait of the walk takes us up Calton Hill (the street), past the old burial ground where David Hume lies, and then up the actual hill. The view from the top is quite possibly the very best in the city, stretching over to the hills of Fife on a clear day. It is topped by a bizarre selection of buildings: the National Monument to Scottish soldiers fallen in the Napoleonic Wars, a monument to Admiral Nelson and the City Observatory (another Playfair building).

Edinburgh’s most grandiose moniker “Athens of the North” is mostly attributed to the National Monument, which was modelled on the Parthenon. The name also stems from Edinburgh’s importance during the Scottish Enlightenment, and its position as a secondary city after the Act of Union – some hoped its influence on London would be analogous to that which Athens had had on Rome. Indeed, 17th century playwright Ben Johnson described it as “Britaine’s other eye”. Note, however, that the climate was not a factor.

Calton Hill is the perfect place to take stock as we near the end of our walk and reflect on the architectural history through which we have just walked. From high up here, we can look out over each neighbourhood and see how the whole patchwork is pieced together to make up the epic city of Edinburgh.

WALK DATA

Distance: 10.4 miles

Typical time: 3h40

Height gain: 483m

Detailed map of the walk:

Start: Scottish Parliament (EH99 1SP); there is a car park in Holyrood Park but do note that Queen’s Drive is closed to vehicles on Sundays. The Parliament is 15 minutes’ walk from Waverley train station, down Calton Road.

Finish: it’s a 20-minute walk from Calton Hill back to the Parliament area, again taking Calton Road. To get back to the station, head down Waterloo Place towards Princes Street.

Terrain: hilly! Walking shoes advised (though after Holyrood Park it is all pavement).

THE ROUTE

- Starting outside the Scottish Parliament building, facing the Palace of Holyrood House, go right down Horse Wynd and onto Queen’s Drive in Holyrood Park (S), Arthur’s Seat to your right

- Take one of the paths rising up and make your way across the Crags, heading SW. The one which skirts along the Crags is called “radical road” but it is not signposted

- At the Southern end, dip back down onto Queen’s Drive and head through the iron gates onto Holyrood Park Road. At the junction at the top, take East Preston street, going straight over at the crossroads with South Clerk Street

- Once you hit Causewayside, you will go straight through a gap in the student halls onto Sciennes. Not before, however, popping into Summerhall for a pint or a look at their current exhibition – depending on how “cul-cha-rul” you’re feeling…

- Turn left at Sciennes, then at the end of the street right onto Sciennes Road heading west for half a mile until you reach the Earl of Marchmont on your left. Follow Marchmont Crescent round to the left until you get onto Marchmont Road, where there is a smattering of shops and cafés

- Head down Marchmont Road to the Meadows, past the cricket pavilion and straight across on elm-lined Middle Meadow Walk

- Follow on straight up the hill (N). If in need of edible reinforcement, do stop off at Peter’s Yard on the way though you will also pass the Stockbridge branch later – sadly the author is not receiving commission for this

- At the top of Middle Meadow Walk, head north down Forrest Road, then bear left at Greyfriars Bobby down Candlemaker Row and into the Grassmarket to your left

- Climb the steps of Castle Wynd on your right which will lead you straight up to Johnston Terrace, and then up again onto Castle Esplanade

- A few paces down the Royal Mile you’ll see the Camera Obscura; take a left down Ramsay Lane and follow it round onto Mound Place

- At the junction with the Mound, take the Playfair Steps down past the Scottish National Gallery onto Princes Street

- Head straight up Hanover Street directly in front of you, turn left onto George Street at the statue of King George IV

- Keep going for half a mile along to Charlotte Square; turn right and walk round its Northern edge. When you reach the imposing West Register House jut through onto Randolph Place and through again onto Queensferry Street

- Cross the road and bear left down Randolph Cliff onto Belford Road. Follow it for half a mile until you reach the Water of Leith and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (here, you can either go straight through the gate onto the river, or through the other one into the gallery’s grounds).

- Once down the steps onto the river, follow it through Dean Village all the way along to St Bernard’s Bridge at Stockbridge. Come up onto Kerr Street and meander through this charming quarter, bearing right along Arboretum Avenue for half a mile until you reach the Botanical Gardens

- Walk through the gardens from the Western to the Eastern edge. As you exit onto Inverleith Row, look for Eildon Street to the left of the playing fields and follow it down into the bottom of the cul-de-sac where there is a cut-through onto a disused railway track, now a tarmac path

- Follow Goldenacre Path for half a mile, through Rodney Street Tunnel into King George IV park

- Climb up through the park. Once back at street level, keep climbing up Scotland Street, round Raeburn Place and up Dublin Street

- At the junction with Queen Street, you will be face-to-face the National Portrait Gallery . Turn left down York Place and follow it along to the Picardy Place junction. Turn right up Leith Street and cross over onto the side of the street where the Omni Centre is.

- With the King James Hotel to your right and Starbucks to your left, turn up steep, cobbled Calton Hill.

- At the top, turn left back on yourself up the steps to the actual hill. More climbing! I promise it’s worth it at the top.

NB: You may wish to cut this rather long walk into chunks: it is roughly halved as you pass through the New Town. Another alternative is to start the walk at the National Gallery of Modern Art (accessed by the no. 41 bus, from Princes Street or Marchmont Crescent) and take the Water of Leith Walkway all the way to The Shore in Leith. The area is served by the no. 35 bus which will bring you back to Holyrood or North Bridge (approximately 200m from Waverley station).

PIT STOPS

The Dogs and Chez Jules (opposite one another on Hanover Street, between George and Queens streets). The epitome of great British and great French cuisine, respectively, and very budget friendly, particularly at lunchtime.

Peter’s Yard (Middle Meadow Walk and 3 Deanhaugh Street, Stockbridge). Open sandwiches on freshly baked Swedish bread which will make you say “wowsers”; similarly delicious coffee and unusual pastries and cakes.

Summerhall (1 Summerhall Place), The former veterinary college is the best addition to Edinburgh’s arts scene for some years. As well as many performing arts spaces and galleries, it also has workshops, a brewery and a gin distillery! Take sustenance in the café or the Royal Dick – they’re both great.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Stockbridge: where else would you find entire businesses dedicated to the retail of Mexican homewares or “posh” candles? There’s also plenty of vintage to be found, as well as brilliant record shop Vox Box on St Stephen’s Street.

Farmer’s markets: in Stockbridge on Sundays, Castle Terrace on Saturday mornings, and all day Saturday in the Grassmarket and on Commercial Street in Leith.

Century General Store: Its strapline “timeless essentials for everyday joy” is very accurate. A family-run business which aims to make itself a real hub in the Marchmont community, selling products “designed with tenement life in mind”. Take it from me: wherever you live, you’ll find something in here you want to take home.

PLACES TO VISIT

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Tel: 0131 624 6200): This is without doubt my personal favourite, and probably the biggest with two buildings as well as the gardens, but really there’s no reason to miss the National Gallery and the Portrait Gallery – all three are free and en route.

National Museum of Scotland (Tel: 0300 123 6789):Brilliant for children – several eras and themes are covered, from prehistoric natural history to the 20th century in Scotland, all set around the impressive three-storey gallery, modelled on Crystal Palace.

Royal Yacht Britannia (Tel: 0131 555 5566): The Queen’s former yacht claims the title of the UK’s no. 1 tourist attraction – I don’t know if it quite merits that, but it certainly is worth a visit.

Leave a Reply