The regeneration of North London’s ancient supply routes

It’s hard to imagine a walk anywhere that more epitomises the transformation of British cities, passing as it does through two massive urban regeneration zones, King’s Cross and The Olympic Park; but also passing through London’s first municipal park.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 11-13 km (7-8 miles); can be reduced to 6 miles by cutting out the Hoxton loop and London Fields loop

- Typical time: 2.5-3.25 hrs

- Height change: 25 metres

- Start: King’s Cross Station (N1 9AL)

- End of this stage: Monier Rd Bridge (E3 2ND)

- Finish if stopping here: Stratford International (E15 2LZ). Thrice-hourly rail services back to King’s Cross, Light Docklands Railway

- Terrain: Straightforward; sturdy footwear recommended

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Many squares and parks around King’s Cross; Culpeper Park, Duncan Gardens, Shoreditch Park, Hackney City Farm, London Fields, Victoria Park, Olympic Park |

| Natural landscapes | Wick Woodland (just north of walk) |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | Regent’s Canal, New River, Hertford Union Canal, River Lee Navigation, River Lea |

| Stunning cityscape | Viewing Platform at top of King’s Boulevard, and another by the Skip Garden; east side of Victoria Park; high ground in Olympic Park |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | Geffrye Museum almshouses |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Upper St, Islington; Duncan Terrace |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | King’s Cross Station (1852), St Pancras Station (1868), German Gymnasium (1865) |

| Industrial Heritage | The Granary (1852), the Canal Museum (1863), Fish Island |

| Modern (post-1918) | One St Pancras Square (2015), Copper Box Arena (2011), The Olympic Velodrome 92011) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Skip Garden Café, Towpath Café, Café Villa D’Aversa, Frizzante, The Victoria Park Café, Counter Café, Timber Lodge Café |

| Quirky Shopping | Camden Passage, Hoxton Market & Street, Netil Lane, Broadway Market, Fish Island |

| Places to visit | London Canal Museum, The Archivist Gallery, Geffrye Museum |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Victoria Park Model Steam Boat Festival (first Sunday in July); Field Day Festival, Victoria Park (Aug) |

City population: 8,538,689 (2011 census)

Urban population: 9,787,426 (2011 census)

Ranking: Largest city in the UK

Date of origin: 43AD

‘Type’ of city: capital city; seat of government, commerce and culture.

City status: Since time immemorial

Some famous inhabitants of the areas around this walk:

Islington: Douglas Adams (writer, Duncan Terrace, parts of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy set in Upper St), Boris Johnson (politician), Sir Walter Raleigh (poet & explorer, Upper St), Joe Orton (playwright, lived & murdered in Noel Rd), George Orwell (writer, Lawford Rd, from whence he would have taken several of his London perambulations), Tony Blair (1986-1997).

Hackney: Alfred Hitchcock (Gainsborough Studios), Edmond Halley (astronomer, Haggerston), Michael Caine (actor, Hackney Downs School), Iain Sinclair (walking writer, Haggerston, close to London Fields), Tony Blair (London Fields 1980-86), Harold Pinter (playwright, Hackney Downs School), the Kray Brothers (gangsters, Stean St, Hoxton), Dick Turpin (highwayman, operated in Kingsland Rd).

Notable architects/planners: The King’s Cross and Olympic Park developments represent two of Europe’s largest urban regeneration projects. Both are notable for their overall master plan and appointment of an array of ‘starchitects’ to create very individual buildings, including Heatherwick and Chipperfield in King’s Cross; and Hadid and Kapoor in the Olympic Park.

Number of listed buildings:

Islington: 1047, of which 12 are Grade I and 33 are Grade II*. Hackney: 548, of which 8 are Grade I and 30 are Grade II*. Tower Hamlets: 943, of which 21 are Grade I and 38 are Grade II*

Films/TV series shot here:

Islington: There’s a rather good Islington Film Locations map which shows you the location of various films and TV programmes.

Hackney: London Fields (1989), Luther (TV series), Rev (TV series), Eastern Promises (2007, Broadway Market), Buster (1988, Regent’s Canal), Odd Man Out (1947, Broadway Market), Pride (2014, Victoria Park)

THE CONTEXT

One of the key strands that brings this walk together as it runs west to east across North London is its interplay with so many of the historic supply routes into the city, and their sequential eclipse as resources were moved first by river, pack horse and self-locomotion (drovers’ herds), then by canal, rail and latterly by road.

Agricultural produce has been shipped in along the River Lea since at least the 12th century. And from the 16th century, cattle and sheep were being driven along the drovers’ route through London Fields down to Smithfield Market. Then, at the start of the nineteenth century, the Regent’s Canal was constructed on an east-west axis to give access to the city via the Thames and onwards to the Grand Union. Finally, the railway arrived into King’s Cross, taking much of the business of the other modes of transport until its freight business was in turn eroded by road hauliers, who you all too easily hear as you go under the A12 East Cross route on approaching the Olympic Park. Oh, and of course the New River Conduit which has channelled fresh water into the city via Islington since the early seventeenth century.

Now a feature of all these supply routes is that they have each been superseded by other modes, and we have been left with the question of what to do with the land made available – and this walk is likely to bring you to the conclusion that one way or another the boroughs and authorities have been able to do a very great deal with the space made available. But you can be the judge of that.

The second big strand of this walk is gentrification, which started in Islington way back in the 60s (the term was coined by the London researcher Ruth Glass in 1964) and in recent years has spread like a tsunami all the way across to Stratford. In many ways this gentrification is typified by the peregrinations of Tony Blair and his family: starting at London Fields in the early 80s; then moving to a leafy part of Islington in the late 80s; then of course to No. 10 (Stage 3 of our walk); and then to Connaught Square in Bayswater (Stage 4 of our walk) as he amassed a substantial personal fortune.

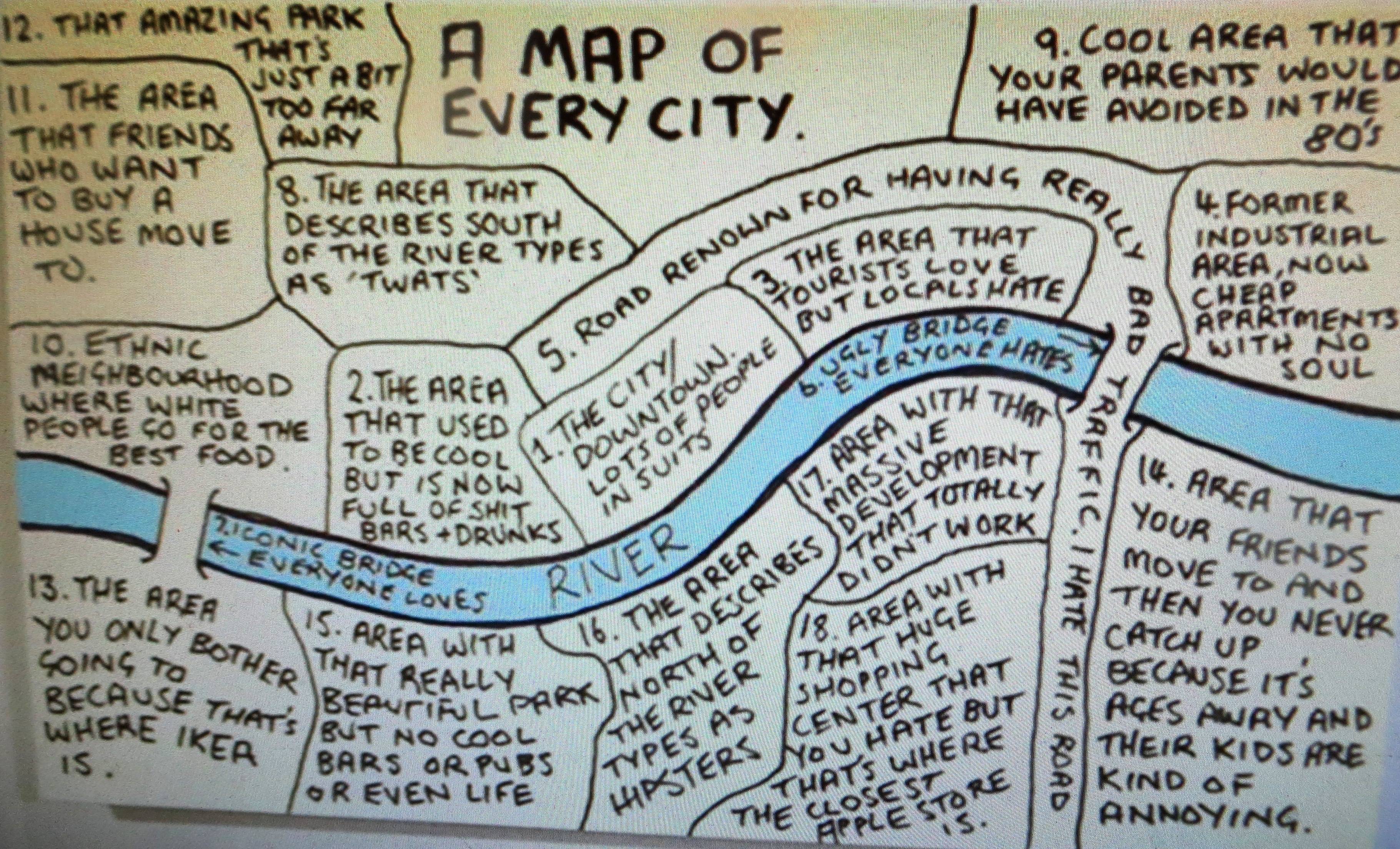

We see evidence of this gentrification process in every nook and cranny we explore and it has made the areas much more apparently accessible to visitors but at a cost to affordability. I leave that thought with you, and my favourite graphic on gentrification:

Copyright: Chaz Hutton

The third big strand of this walk is the number of famous writers who have used this area as the backdrop for their bipedal wanderings.

First by George Orwell in the 1930s, when he started to explore the poorer parts of London. On his first outing, he set out for Limehouse Causeway, spending his first night in a common lodging house, dressed as a tramp. He recorded his experiences of the low life in ‘The Spike’, in which he details his experience of staying overnight in the casual ward of a workhouse (colloquially known as a ‘spike’) in the East End close to where we walk. These experiences also went on to inform his famous novel ‘Down & Out in Paris and London’.

Orwell’s observations are a salutary reminder that walking way back then was not a leisure activity, but born out of necessity. A tramp was not allowed to stay more than one night in each ‘spike’ and would always be moving on looking for work. Vagrancy (aka wandering aimlessly without a specific goal) was a crime punishable by prison or a month’s hard labour up until the last century. Now it is a literary pursuit called psychogeography.

Then, by Iain Sinclair, who lives near London Fields. Iain Sinclair is the (unintentional) father of a whole genre of literature devoted to psychogeography, using walking often at random as a way of experiencing and understanding a city in its unadorned and unrehearsed state, the bad bits as valid as the good bits to the overall experience. This culminated in his book ‘London Orbital’, which describes a series of trips he took tracing the M25 on foot (the rule being he had to keep it within earshot).

And more recently by Will Self, self-appointed psycho-geographer royal. As he writes: “You don’t know London until you’ve physically walked around it and out of it. Since the late 1990s, it’s been a way to deal with my issues with London and my issues with myself simultaneously. Walking aids the mind in so many ways: it’s not for nothing that Nietzsche said, ‘I never trust an idea that didn’t come to me on a walk.’”

“The first time I actually reached open country in a single day I walked from my house to Springfield Park in Upper Clapton, from where I joined the River Lea, the course of which led me all the way to Epping Forest.

“I crossed over the M11 by footbridge and stood there for a while watching the faces of the drivers as they streamed away from the city, the stress of their working days etched into their tense faces. The path ahead disappeared into twilight woodland and within minutes I felt as if the city of my birth had disappeared as well. It was an eerie moment — and I believe only possible because I’d left town on foot. It was because I’d experienced every inch of the way, registered it with nerve and sinew and muscle and mind, that I was now gifted this extraordinary sense of release.”

THE WALK

Cities just aren’t what they used to be. They are SO much better. Nowhere is that more evident than when arriving in the revitalised King’s Cross, my London terminal. Back in the 1970s, they had done everything they could to disguise the grandeur of Lewis Cubitt’s majestic station, with a temporary booking hall tacked on to the front that totally extinguished the wow factor, with a sprinkling of the down and outs that made King’s Cross their home in those days.

Today, the temporary structure is long since gone, the front of the station – now called King’s Cross Square – has been beautifully crafted with raised stone block seating areas, trees, art installations and a regular food market; and on the west side of the station, the tour de force, the new booking concourse.

The steel structure of the roof has been described as being “like some kind of reverse waterfall, a white steel grid that swoops up from the ground and cascades over your head”. Others see it in a quite reverse way, as a tree-like canopy of intersecting branches. But no matter how your visual brain works, it gives you that most important quality of all, a sense of spatial abundance and a unity of structure between old and new, so lacking in the cramped mish-mash of the previous incarnation.

Coming out of the station, we enter that highly unusual thing, although you can’t actually see it, a brand new postcode. N1C was coined for this major area of regeneration around King’s Cross, 26 hectares (65 acres) in total comprising a mix of offices, houses, leisure and open spaces. For an urban rambler, one of the best bits about it is the sheer number of new urban spaces that have been created, covering 40% of the total space – King’s Cross Square, Battle Bridge Place, Pancras Square, Granary Square, Lewis Cubitt Square & Park, The Skip Garden and Handyside Gardens – all well constructed and great spaces to experience. Green roofs, green walls and trees have been planted in abundance. In these early days of the development, people appear to be wandering around in a state of awe that something so appealing could be created.

This is one of the most exciting ‘greenings’ of a city anywhere in the UK, and it is a fabulous template for future initiatives – retaining historic features, adding great modern design takes and laying out oodles of public and green space.

The first open space we come to is Battle Bridge Place, named after an ancient crossing of the (now underground) River Fleet. A myth grew that this was the site of a major battle around AD 60 between the Romans and the Iceni tribe led by Boadicea. The suggestion that Boadicea is buried beneath platform 9 or 10 at King’s Cross Station is a subsequent urban myth, now somewhat overtaken by the fact that the Harry Potter bandwagon has taken up residence there; well on Platform 9 ¾ to be precise.

The giant ‘birdcage’ in Battle Bridge Place is Jacques Rival’s artwork IFO (Identified Flying Object). The huge white installation stands 9m high, and the bars are wide enough for people to walk through and enjoy the swing that hangs at its centre. By night, the artwork comes alive in a brilliant array of neon colours. Whilst the IFO is mostly ‘earthbound’, on special occasions the eye-catching structure is hoisted up into the air to hang freely and light up the night sky.

Designed by Edward Gruning, the German Gymnasium was the first purpose-built gymnasium in England and was influential in the development of athletics in Britain. It was built in 1864-65 for the German Gymnastics Society, a sporting association established in London in 1861 by Ernst Ravenstein. The National Olympian Association held the indoor events of the first Olympic Games here in 1866. These games continued annually at the German Gymnasium until the White City Games in 1908. The main exercise hall was a grand and elegant space with a floor to ceiling height of 57ft. Long forgotten sports were practised here, including Indian club swinging and broadsword practice. The building has recently been re-opened as the German Gymnasium restaurant. Many of the original features remain, such as the vast laminated timber roof trusses, and the original cast iron hooks from which budding Olympians swung.

A giant pin oak marks the entry point to Pancras Square from Battle Bridge Place. It was transported all the way from a nursery in Germany and was already 12 metres tall and 63 years old when it was lowered in by crane. It’s one of 400 mature trees planted at King’s Cross.

We passed into Pancras Square walking past One Pancras Square, an 8-storey office building designed by David Chipperfield. It is wrapped in 396 columns faced in a sleeve of elaborately moulded cast iron in a basket weave pattern, intended to symbolise the industrial heritage of both the railways and the gas holders. I’m getting to like this building.

With lawned areas and seating beneath mature trees, Pancras Square is both a green route from the stations to the canal and a place to pause and relax. Water cascades through the space in a series of stepped terraces flowing towards the view of the St Pancras Chambers Clock Tower. Someone took the trouble to line up the view in Capability Brown style and it really works.

We threaded our way through here and then re-joined the King’s Boulevard further up. The boulevard is a new road, with good quality stonework and an avenue of newly planted plane trees. Why are plane trees London’s city street tree of choice, accounting for over half of the city’s tree population? The London Plane is in fact a hybrid between the American Sycamore and the Oriental Plane. It first came about in the old Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens after some illicit coupling between the two species and turned out to have very hardy characteristics. The attractive camouflage bark breaks away in large flakes so that the tree can cleanse itself of pollutants. It also requires little root space and can survive in most soils. As a result, London plane trees were planted en masse at a time when London was black with soot and grime. Taking a cue from the plane-lined boulevards created in Paris from around 1850, it was felt that tree-lined avenues added elegance and well-being to the cityscape.

At this point, people generally start asking where the Google building is, supposedly the ‘anchor tenant’ of the whole enterprise. Well, in fact, building work is not due to start until 2018. It’s going to be on the east side of the Boulevard, where the Railway Children is currently showing. Described as a ‘landscraper’, it will be as long as the Shard is high, almost the entire length of the Boulevard. British designer Thomas Heatherwick will be responsible for the new design. He has already worked successfully on the search giant’s new Californian headquarters. The plan shows an 11-storey building, with a rooftop garden, split over multiple storeys and themed around three areas: a ‘plateau’, ‘gardens’ and ‘fields’, planted with strawberries, gooseberries and sage.

The Goods Yard complex, just to the north of the canal, also designed by Lewis Cubitt, was completed in 1852. The complex comprised the Granary Building, the Train Assembly Shed, and the Eastern and Western Transit Sheds. The Granary Building was mainly used to store Lincolnshire wheat for London’s bakers, while the sheds were used to transfer freight from or to the rail carts. Today, the elegant Granary building is a creative warehouse, home to Central Saint Martin’s Art College. Worth popping inside a moment and taking a look at the well-crafted internal space.

In front is Granary Square, where barges used to unload their goods from the canal. Its aquatic history has been worked into the new design, which is animated with over 1,000 choreographed fountains, each individually controlled and lit. The transit sheds to the west are in the process of being converted by Thomas Heatherwick into shops, as well as restaurants, galleries and music venues. All the traditional features will be retained, including the original stables located under the loading platforms. We then strolled around the left-hand side of the Granary Building into Lewis Cubitt Square and up Lewis Cubitt Park (somewhat compromised during the conversion phase of the transit sheds). The arching water jets are another echo of the arcs of the engine sheds a few hundred yards south.

The Skip Garden is a sustainable community garden. Through the medium of sustainability, the young people involved have developed new skills and networks, learned how to grow food, as well as how to market and sell their produce. There’s another good viewing platform here and the café is fun too.

Handyside Gardens, which we came to next as we headed back towards the canal on the east side of the Granary Building, is inspired by the railway. The geometry follows the pattern of the railway sidings that once ran through the site, while the planting is inspired by the growth found on railway embankments. The gardens are beautifully landscaped, with places to sit and a water rill that meanders through the park from a children’s play area.

Then we are back on the canal, and if you can drag yourself away, finally time to start heading east. But hang on a bit, before we can get going properly, my walking companion spots ‘Words on the Water’, a floating bookshop on a narrowboat, moored to the side of the Granary Quay courtesy of some enlightened thinking on the part of the Canals & Rivers Trust (join it, it’s a great organisation). When the weather is good, it’s the impressive site of the books lining the top deck that make even the least of book lovers want to browse and buy.

This is the book shop that long ago met with Penguin’s wrath for using their iconic front covers for some publicity (to sell books, believe it or not). This was the bookshop owner’s response: “A visit by a human being to our boat to have a chat may have been a more creative and potentially mutually beneficial way of saying hello, but that is why we are never going to be successful corporate lawyers or executives and are forced to make do with waking up at 10am, watching the moorhen chicks and swans over coffee in the morning, then discussing literature and promoting reading on a boat all day, making just enough cash for a modest meal out for supper. We hope your combative, competitive approach gives you a much more rewarding working day.” Canals seem to breed alternative lifestyles, and usually it would seem very contented ones.

We finally got going, under the Maiden Lane Bridge at York Way and heading east. The railway lines in and out of King’s Cross Station go under the Regent’s Canal (unlike St Pancras, where they go above). During the Second World War, the Luftwaffe bombers targeted this section of the canal. Had the canal been breached here the railway line would have been flooded and traffic to and from the north severely disrupted. Stop-locks were fitted to the canal on either side of the railway line. Once the air-raid sounded the stop-locks were closed. The Eastern set can still be seen embedded within the canal bank just after this bridge.

In 1812, the Regent’s Canal Company was formed to cut a new canal from the Grand Junction Canal’s Paddington Arm to Limehouse, where a dock was planned at the junction with the Thames. The architect John Nash oversaw its construction, using his idea of ‘barges moving through an urban landscape’.

Completed in 1820, it had the misfortune to be built too close to the start of the railway age to be financially successful, and at one stage only narrowly escaped being turned into a railway itself. But the canal went on to become a vital part of southern England’s transport system. Together with the Grand Junction Canal and the associated routes to the Midlands and the north, it carried huge quantities of timber, coal, building materials and foodstuffs into and out of London. In fact, long-distance traffic continued to use the canal into the 1960s.

We next pass Battlebridge Basin on the opposite side, which used to be a major unloading point for cargo. In 1856, the Swiss-born Carlo Gatti had started importing ice into London. By 1863 he had built himself a large unit, that is now home to the London Canal Museum. Huge stacks of ice were cut from Norwegian fjords and shipped to the Limehouse Canal Basin and thence on barges to this storage unit. The ice was stored in two wells, 10ms wide by 13 ms deep, before being transported to the city centre.

And then ahead the Islington Tunnel comes into view, at which point we need to take the overland route through the heart of Islington, as the barge horses would have had to do. The barges originally had to be ‘legged’ through the tunnel, basically men lying on their backs and propelling the barge forwards with their feet on the tunnel roof as the locomotive power. In 1826 the tunnel was upgraded with a steam tug attached to a continuous chain on the canal bed which would heave barges through.

Our route runs directly above the tunnel initially, going through Culpeper Community Garden, a beautiful public space that serves both as a city park and as an environmental community project. It is a unique locally-run project where people from all walks of life come together to appreciate and enhance their environment. The garden is less than a hectare in size but contains 65 plots for local people and groups without gardens, as well as a lawn, communal flower beds, rose arbour, pond and wildlife area. Created in 1982 from a derelict bomb site, it is one of the oldest community gardens in London and is a fabulous example of just what regeneration is possible with impassioned residents.

Upper Street is unusual in being one of the few streets in London to have a ‘high’ pavement. This was constructed in the 1860s to protect pedestrians from being splashed by the large numbers of animals using the road to reach the new Royal Agricultural Hall (re-purposed in 1986 as the present Business Design Centre); as a consequence, the pavement of the street is almost a metre above the road surface in some places.

Islington Green is not an old village green like others in London, but a surviving patch of common land that was carved out of old manorial wasteland, where local farmers and tenants had free grazing rights. The original land was far more extensive but was largely built over in the 19th century. In 1885, Henry Vigar-Harries described Islington Green “where the young love to skip in buoyant glee when the summer sun gladdens the air”, which would not have been a bad description of the day we were there too.

At the southern end of the green, we came across the statue of Sir Hugh Myddleton, designer of the New River, that became so vital to London’s water supply from the 17th century onwards (it still supplies a tenth of the city’s drinking water). The statue incorporates a fountain, which is no longer functioning. We will walk along a part of the New River in a few minutes.

Camden Passage is famous for its antique trade and hosts an antique market on Wednesdays and Saturday mornings. The passage was built as an alley along the backs of houses on Upper Street in 1767. Turning left at Charlton Place and then right into Duncan Terrace brought us into a stretch of green space that runs along the old course of the New River (not new and not a river as local historians love to point out); first Colebrooke Row Gardens and then Duncan Terrace Gardens. This is the southerly segment of a series of linear public spaces known as the New River Walk, built over the route of the historic New River, a constructed water channel completed in 1613 to provide a clean water supply to London. The New River runs from its source in Hertfordshire, taking water from the River Lea to a reservoir at New River Head, close to Sadler’s Wells Theatre where, amongst other things, water from the river was used to flood a large tank to stage an. The Siege of Gibraltar, for example, mounted in 1804, deployed 117 model ships created by the Woolwich Dockyard shipwrights which were capable of firing their guns. (see our walk North London Stage 2: The New River from Alexandra Palace to Islington )

These gardens are absolutely delightful and might be a good place to pause for reflection or a sandwich. If you see a mop of blonde hair on a cycle it’s probably Boris Johnson returning home to his abode overlooking the Gardens. Their thinness reminds me of my favourite linear gardens, wedged in the central reservation of a dual carriageway at Vancouver International Airport – a great place to hang out if you are a little early for your flight and wish to imagine yourself to be still in the Rockies.

We finally managed to drag ourselves back on the canal at Duncan St, sticking to the north side and heading east once again. We then took off south through Hoxton at New North Rd Bridge, but you might, by all means, decide to stay on the canal up to Broadway Market; one notable benefit of your lack of adventure would be the pleasure of experiencing the wonderful Towpath Café just after the Whitmore Rd Bridge.

You would also pass the Kingsland Basin if you stick to the canal route. One of the largest canal basins in London, it was built south of the planned development of De Beauvoir Town in the 1830s; and allowed easy import and storage of building materials to the site. Today Kingsland Basin is home to Canals in Hackney Users Group (CHUG), a local charity. It was set up in 1983 to promote the use of the canal in Hackney. CHUG manages and maintains the moorings. This tightly knit community brings together people of all ages, and from all walks of life. The self-managed moorings, unique in the UK, provide much needed affordable residential moorings in central London; and a touch of the ‘Rurbanite’ existence – one of the narrow boats has been converted into a vegetable garden complete with a duck coop.

The Hoxton ‘loop’

Anyway, we took off SE through Shoreditch Park. It was originally created in the 1970s on an area of terraced housing that had been devastated by the Blitz, and then used for prefabs. In 2005 an extensive excavation was carried out by archaeologists from the Museum of London to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II. The excavation examined housing of the time and investigated the damage caused by aerial bombing and missiles. It was featured on the Time Team TV programme.

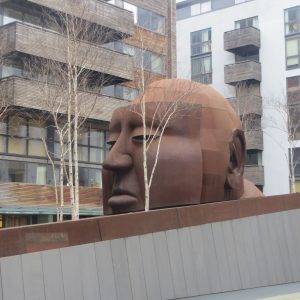

On the north side of the park are the Gainsborough Studios. This is the site of the film studios where Alfred Hitchcock made his British classics ‘The Lady Vanishes’ and the ‘39 Steps’ in the 1930s. A (rather large) sculpture of Alfred Hitchcock by Antony Donaldson is located within the courtyard. Hitchcock was born in nearby Leytonstone and trained as a draughtsman and designer.

The park has sports facilities and a children’s playground, and what claims to be London’s only outdoor beach volleyball courts; and rather surprisingly there is an 85-tonne granite boulder here. It turns out it didn’t arrive from outer space but was in fact transported from Cornwall on a re-enforced HGV lorry with a police escort. It was the inspiration of artist John Frankland, who said the idea came to him while on a pebble beach during a holiday in Cornwall. “I just started looking at them as amazing objects and interesting things in themselves,” he explained. “But if you change the context of where they are found, you change the meaning. The boulder is different in its new home – and acts like a magnet. People walk up to it and ask questions. It’s absolutely fantastic.” You are welcome to climb on it, and there are several routes of varying difficulty to the top. But did you find yourself asking any question other than ‘what an earth is that boulder doing here?’

As we exit the park in the south-east corner we pass through a memorial garden to Dorothy Thurtle. Married to Ernest Thurtle who became MP for Shoreditch, Dorothy was the daughter of George Lansbury, leader of the Labour Party in the 1930s and was herself a pioneer for contraception and Abortion Law reform. There is a charming curved stone bench in her memory. Just a small reminder of how much social and political history there is in this area.

Our route then took us just to the south of Hoxton Market. The market was originally founded in 1687 and used to be the cornerstone of the local community; but, from the 1980s onwards, it dwindled as supermarkets gained a stranglehold. It has since been re-launched as a Saturday-only market, still selling everything from clothes to food to toiletries, but also now notable for its fashion.

Next up the Hoxton Trust Community Garden. It was laid out by the Hoxton Trust in the early 1980s, funded by Hackney Council. The site was once that of a 18th-century lunatic asylum, Holly House, later built over with housing. It is landscaped on a number of levels on hummocky terrain, with a variety of flower beds and shrubs, with paths and seating within the lawns. It contains a 19th-century cupola with a clock from the old Hackney Work House at Homerton, which is quaint but somehow very incongruous, especially with a glasshouse under it and decorated plastic chairs around it as we found it.

Hoxton St is an extraordinary mix of passé and hip shops. I especially liked www.monstersupplies.org. Their website declares that the home page has been automatically translated for humans…

And then a sudden transition from 1950s housing estates to the early eighteenth century as we spot the Geffrye Museum (Grade I listed), elegantly set in the former almshouses of the Ironmongers’ Company, built in 1714. This museum shows the changing style of the English domestic interior in a series of period rooms dating from 1600 to the present day. The emphasis is on the furnishings, pictures, and ornaments of the urban middle classes of London. You can explore the museum’s award-winning walled herb garden and period gardens which show how domestic gardens have changed over the past four centuries. Inspired by Shoreditch’s history as a centre of horticulture and market gardens, the four period (17th-20th century) gardens are chronologically arranged to explore the links between home interiors and gardens.

St Mary’s Secret Garden: This Hackney project has four interlinking areas: a natural woodland, a food growing area (including vegetable beds and fruit trees), herb and sensory garden and an area of herbaceous borders. It is named after a former nearby church destroyed by World War II bombing. The garden is open Mon-Fri. Find out more about this enlightened community project at www.stmaryssecretgarden.org.uk We paused outside before going in, and were greeted by a passer-by who invited us to take a look around. Several volunteers happily toiling away, clearly very therapeutic and relaxing for them. Such a peaceful place in the middle of a built-up area.

We cut through an estate at this point, past Fellows Court and through Weymouth Terrace Square, in the style of Georgian squares – the only problem being it is not very well maintained, which creates something of a scruffy air. But at least you don’t need a key to get in, unlike the more salubrious squares we encounter on Stage 4 of our walk.

Haggerston Park (6 hectares, 15 acres) was originally created in the 1950s. It was carved out of an area of derelict housing, a tile manufacturer and the old Shoreditch gasworks, which had been hit by a V-2 rocket in 1944 and badly damaged. It has some really nice touches, including the Woodland Walk, where to all intents and purposes, you could be in deep countryside.

In the 1980s the park was extended to the south and the Hackney City Farm created out of a run-down lorry park. City Farms exist to bring the countryside and its activities to urban people. The movement began in the 1970s when Kentish Town City farm was founded, and there are now over sixty city farms, thriving although generally experiencing sharp reductions in council funding. They typically use otherwise derelict land and involve local people in their establishment and maintenance.

The facilities at Hackney City Farm include a farmyard, area for grazing, garden and a tree nursery with butterfly house. The amenity encourages children to learn about the natural environment, growing vegetables and caring for animals. The farm is home to a range of animals including poultry, sheep, rabbits, bees, pigs and a donkey. The day we were there were two school parties having a lot of fun and being challenged – this is a fabulous resource.

Next, we trudged up Goldsmiths Row, past the Albion mock-Tudor pub – if the thought of watching football in an east end local appeals, then try this pub. Decorated with a West Bromwich Albion badge on the exterior, the interior follows suit with flags, scarves, trophies and pictures celebrating the famous and the infamous of the sport.

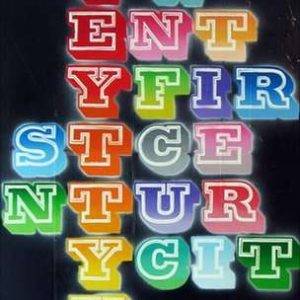

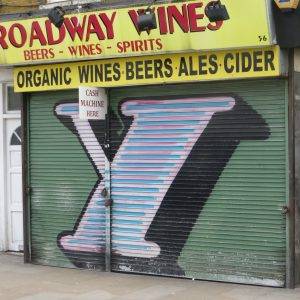

But Goldsmiths Row has something else very interesting – the start of something of a graffiti trail, by well-known street artist Eine. See the google map at Eine shop fronts in and around Shoreditch. Suffice to say, at this point you head past Z (89, Lock & Davies and C (News Corner); and in Broadway Market itself you can find P (Piper Flooring), J (Joy Indian Cuisine), U (Gent’s hair Stylist), Y (Broadway Wines) and B (57, Tidiman Butchers). Mind you, on a normal working day most of the security shutters will be up, so if this is your thing maybe best to go on a Sunday.

Ben Eine’s bright, colourful letters have transformed streets around the world, most famously ‘Alphabet Street’ – the shutters and murals he painted in Middlesex Street (E1 7HT, SE of Liverpool St). The art world knew he had ‘arrived’ the day that David Cameron gave one of his works, ‘Twenty-First Century City’, as a gift to President Obama. Respectability for graffiti artists is somehow a contradiction in terms, though, and Ben admitted it had been a ‘weird day’.

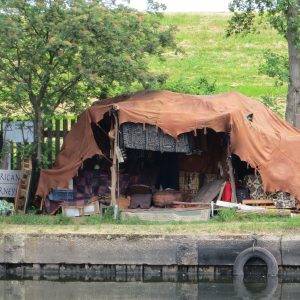

Broadway Market is a bustling shopping street full of quirky, independent shops and very inviting cafés. It has been home to market traders since the 1890s and still has a thriving market on a Saturday. Stalls range from the classic (sweet seasonal cupcakes from Violet) to the exotic (The Arabica Food & Spice Company do a mouth-watering range of meze, as well as Damascene falafel wraps). Spices, cheeses, breads, rare-breed meat, luscious cakes and olives are all easily found. The market is also popular for its vintage and new designer threads, old Vogue patterns, buttons, Ladybird books, flowers and crafts.

We ventured into the Café Villa D’Aversa, which looked very inviting, but there didn’t seem to be anywhere to sit. But as our coffee arrived and we glanced around estimating whether any spaces were wide enough to squeeze into, so faces looked up from their animated conversations, and in some organic way space suddenly became available, between a couple of hipsters on one side and two young families on the other. It almost felt like being invited into someone’s home; and our new neighbours adjusted the cushions and seats to make sure we would be comfortable. Needless to say, we spent much too long in that café and then made a fuss over the new arrivals when they in turn were looking for a space.

London Fields (12.7 hectares, 31.3 acres) was first recorded in 1540. At that time it was common ground and was used by drovers to pasture their livestock before taking them to market in the city. London Fields was the last grazing area for the livestock, before their final stop at Slaughter Street in Brick Lane or East Smithfield. Today it is rather a flat green space (I guess it was always flat….), and is home to a wildflower meadow and a woodland section where the rangers have built enormous, rustic furniture out of fallen branches. A great place to escape on a hot day, but it lacks the space and intrigue of Victoria Park, which we will soon come to.

The writer Iain Sinclair, the country’s best-known psychogeographer (he would probably hate that title) lives near here in Albion Drive. In 1997 he published ‘Lights Out For The Territory’, his seminal work. Walking the streets of London, he traces nine routes across the territory of the capital. Connecting people and places, redrawing boundaries both ancient and modern, reading obscure signs and finding hidden patterns, Sinclair creates a fluid snapshot of the city. The route we are interested in today is his first chapter, ‘Skating On Thin Eyes: The First Walk’.

It begins: “The notion was to cut a crude V into the sprawl of the city, to vandalise dormant energies by an act of ambulant sign making. To walk out from Hackney to Greenwich Hill, and back along the River Lea to Chingford Mount, recording and retrieving the messages on walls, lampposts, doorjambs: the spites and spasms of an increasingly deranged populace. Dynamic shapes, with ambitions to achieve a life of their own, quite independent of their supposed author. Railway to pub to hospital: trace the line on the map. These botched runes, burnt into the script in the heat of creation, offer an alternative reading — a subterranean, preconscious text capable of divination and prophecy.”

“Armed with a cheap notebook, and accompanied by the photographer Marc Atkins, I would transcribe all the pictographs of venom that decorated our near-arbitrary route. The messages were, in truth, unimportant. Urban graffiti is all too often a signature without a document, an anonymous autograph. The tag is everything, as jealously defended as the Coke or Disney decals. Tags are the marginalia of corporate tribalism. Their offence is to parody the most visible aspect of high capitalist black magic. Spraycan bandits, like monks labouring on a Book of Hours, hold to their own patch, refining their art by infinite acts of repetition.”

Dense, great prose. Not sure though what he would make of Ben Eine and his Alphabet Street, which seems to have done all the hard work for him!

He is decidedly disappointed by London Fields because of its lack of graffiti; “Not a squiggle, not a curse; no conjuring symbols carved into the peeling bark of the still impressive avenue. Even the titular deities, a Cockney/Aztec pearly king and queen rendered in cement and multi-colured tesserae, are undefaced.”

No sign of any graffiti anywhere…

It’s been a while since we’ve been on the canal, and now it’s a short run to Victoria Park (86 hectares, 213 acres), London’s first public park and today a beautifully managed space.

Victoria Park was opened in 1845 after a local MP presented Queen Victoria with a petition of 30,000 signatures, campaigning for a park to allow the working classes to escape from the grime of city life and experience some fresh air and green spaces. The aim was to make it a kind of Regent’s Park for the east; and it originally had its own Speakers’ Corner which drew, amongst others, the socialist William Morris and Annie Besant, the women’s rights activist.

In the Second World War, much of the park was taken over by the war effort, and was used for allotments, military stations, anti-aircraft guns and barrage balloon sites; even the park railings were melted down to be reused. This inevitably resulted in much damage and it has only been in recent years, with major Lottery grants and refurbishments, that it has been restored to something like its former glory.

Walking through the park today is an absolute pleasure. It is beautifully maintained and there is so much to do and look at. The lakes are a fantastic feature, and there are several interesting structures: the ornate Bonner gates on the west side, the Dogs of Alcibiades guarding them, the bandstand and the drinking fountain erected by Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts in 1862 to bring fresh water to the local populace. And on the east side of the park, there are two pedestrian shelters, originally located on the old London Bridge which was demolished and replaced in 1831. They look very out of place but are delightfully quirky.

And we passed by the Model Boating Lake, home to the oldest model boat club in the world, the Victoria Model Steam Boat Club (some great old pictures) founded in 1904 and still holding frequent Sunday regattas. The first Regatta of the year is held on Easter Sunday and the Steam Regatta on the first Sunday in July. The appeal of model boats seems timeless. As a 1907 report noted, the Club meets pond side on Saturday afternoons ‘before an enormous public of small boys’ as well as on Sunday mornings ‘before a wall of charming young ladies’.

It was as we were walking towards the eastern end of the park that we got our first glimpse of the Olympic Stadium, looking like a flying saucer landed in the middle of the urban landscape. It took our breath away when we first saw it, instantly bringing back memories of that great Olympic summer of 2012.

Like its 1766 predecessor, the Limehouse Cut, the Hertford Union Canal was intended to provide a short-cut between the River Thames and the River Lee Navigation. It allowed traffic on the Lea heading for the Thames to bypass the tidal, tortuous and often silted Bow Back Rivers of the Lea via a short stretch of the Regent’s Canal and provided a short-cut from the Lea to places west along the Regent’s Canal. It was opened in 1830 but quickly proved to be a commercial failure. It was acquired by the Regents Canal Company in 1857 and became part of the Grand Union Canal in 1927.

There is what amounts to an ‘institutionalised’ graffiti wall at the Wick Lane Lock, with people spraying away furiously with aerosols the day we passed. Presumably, Iain Sinclair passed this point on his V search, but not quite sure what he would make of it today.

We crossed over the footbridge onto Fish Island, once an industrial enclave but now something of an artistic hot spot – apparently it has one of the highest densities of fine artists, designers and artisans in Europe, with a recent study identifying around 600 artists’ studios. There did happen to be a photo shoot on the bridge the day we were crossing, but I noticed they stopped shooting as we passed by, so clearly they were not after the urban rambler look.

Fish Island is bounded by water on two sides, but that really doesn’t feel sufficient for it to be called an island. The real reason is in the street names – five are named after freshwater fish – Smeed Rd, Dace Rd, Monier Rd, Bream Rd and Roach Rd – whilst the other three are full of water imagery: Beachy Rd (self-explanatory), Wyke Rd (an old term for a safe landing place) and Stour Rd (an East Anglian river). These names were conjured up by the Gas Light and Coke Company back in 1865 when they bought up the land to develop it – no doubt one of their employees was a keen fisherman. So much more inventive than some of the modern street names that dullen British suburbs today, the sprinklings of herbs and spices and the like.

We stopped off at The Counter Café and had an awesome vegetarian meal on their jetty by the canal. We walked through a gallery space to get to it and enjoyed the views of the Olympic Stadium on the other side – there’s so much to look at all round.

Opposite Monier Rd is the Monier Rd Bridge that spans the River Lee Navigation Channel into the Olympic Park; and on your left, there is a 19th-century chimney, the letters on it referring to the MK Carlton Shoe Company that used to have their factory here.

Looking up at the Olympic Stadium brings back poignant memories from 2012 – all those days spent on the internet trying to get tickets and finally the thrill of securing some for the main stadium, being washed along by an enthusiastic crowd and superbly upbeat and helpful games ambassadors, for a day of triumphs never to be forgotten!

We are now entering the Canal Park (5 hectares, 12.4 acres), which covers approximately 1.2km of linear parkland along the Lee Navigation Canal, from the Wick Woodland just north of the A12 to Old Ford Island to the south. A varied set of landscapes and plants includes woodlands, meadows, coppices, reed beds and green walls, plus a lot of benches for sitting on and some play areas for good measure. There is also a practical reason for all this riverside planting. Two 42-inch Thames Water mains run the length of the Canal Park and create a significant no build zone above them, even restricting the types of tree that can be planted.

But beware; Sweetwater is going to pop up here in the next few years – with 650 new homes. What a great place to live. Due to be completed in 2023. Enjoy the views whilst you can.

An aerial impression of Sweetwater

The River Lea is a major tributary of the River Thames. According to the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, the river was used by Viking raiders, and King Alfred changed the level of the river to strand Guthrum and his fleet. In more peaceful times, it became important for the transport of grain from Hertfordshire, but navigation of its southern-most tidal reaches of Bow Creek was difficult due to its tortuous meanders.

There is documentary evidence that the river was altered by the Abbot of Waltham to improve navigation in 1190. The first Act of Parliament for improvement of the river was granted in 1425, this also being the first Act granted for navigational improvement anywhere in England. Local landowners were authorised to make improvements to the river including scouring or dredging, and could recoup the cost of the work by levying tolls.

Throughout the centuries there has been conflicting pressure on the resources of the river: as a major source of fresh water for Londoners to drink, via the New River extraction; as a power source for mill owners; and as a navigation channel for the barges bringing in materials and produce from the countryside.

The navigation issues were addressed by John Smeaton in the 1760s when he surveyed the river and produced a report, in which he recommended that the staunches should be replaced by pound locks and that several new cuts should be made. These recommendations were granted in an Act of 1767, which authorised the construction of several new stretches of canal, including the Hackney Cut from Lea Bridge to Old Ford (this is the one we are walking along), and the Limehouse Cut to bypass the tight bends of Bow Creek near the River Thames (Stage 2 of the walk).

Much more recently, the navigation played a vital role in the construction of the Olympic Park, as development and dredging in the early 2000s allowed 350-ton barges to carry materials in and refuse away from the site.

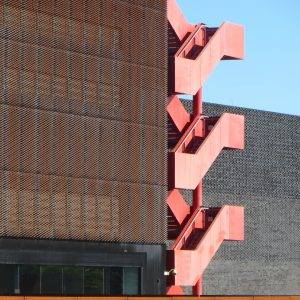

We turned up right away from the Lee Navigation past the Copper Box Arena, a world-class sports venue that became known during the London 2012 Games as the ‘box that rocks’; it works visually in its own modernist way, with the copper coating aging beautifully (think Angel of the North and Broadcasting Tower in Leeds).

The Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (227 hectares, 560 acres) which we now cross is a huge and delightful space. One or two design critics have been a bit critical of it but, to me, it has a modern quality about it not present in any other British park that I have visited, where the dominant era remains Victorian. This park feels modern, open, forward-looking, Scandinavian even – and above all it has oodles of space!

Soon we are looking up towards the Velodrome, another stunning building which enhances the overall look and feel of the park. The concave form of the Velodrome rests lightly on its landscaping, ‘like a Pringle crisp on a bed of spinach’ as someone so perceptively observed.

Take a picture of yourself perhaps in front of the Olympic rings (this one is my son’s hockey team when they were playing in a hockey tournament at the Lea Valley Hockey Centre – he’s the good-looking one)

This part of our walk finishes at the Timber Lodge Café. I love this place, that rare thing in a park, a modern café that has been well built and beautifully landscaped around it. Mind you, the TripAdvisor cognoscenti aren’t so sure. At the time of writing, it was ranked #13,356 of 19,547 Places to Eat in London! Ah well, be your own judge, me vs. Trip advisor (which I love, by the way).

Fancy walking to the M25?

If you’re feeling like an adventure at this point, you have the option of following the River Lea all the way out of London and reaching the M25 and beyond.

We walked the 13 miles from the Olympic Park to Cheshunt, following a very straightforward route alongside the River Lea, slipping bit by bit from a largely built-up area to ‘edgeland’ areas of power stations, re-cycling plants and crumbling factories via Enfield Lock (where the Enfield Rifle was manufactured), under the M25 and out into the countryside.

The perambulist Iain Sinclair writes: “Without the Lea Valley, East London would be unendurable. Victoria Park, the Lea, the Thames: tame country, old brown gods. They preserve our sanity. The Lea is nicely arranged – walk as far as you like then travel back to Liverpool Street from any one of the rural halts that mark your journey. Railway shadowing river, a fantasy conjunction; together they define an Edwardian sense of excursion, pleasure, time out.”

And the writer Will Self is quite certain of the psychogeographical importance of walking out of a city:

“You don’t know London until you’ve physically walked around it and out of it. Since the late 1990s, it’s been a way to deal with my issues with London and my issues with myself simultaneously. Walking aids the mind in so many ways: it’s not for nothing that Nietzsche said, ‘I never trust an idea that didn’t come to me on a walk.’”

“The first time I actually reached open country in a single day I walked from my house to Springfield Park in Upper Clapton, from where I joined the River Lea, the course of which led me all the way to Epping Forest.

“I crossed over the M11 by footbridge and stood there for a while watching the faces of the drivers as they streamed away from the city, the stress of their working days etched into their tense faces. The path ahead disappeared into twilight woodland and within minutes I felt as if the city of my birth had disappeared as well. It was an eerie moment — and I believe only possible because I’d left town on foot. It was because I’d experienced every inch of the way, registered it with nerve and sinew and muscle and mind, that I was now gifted this extraordinary sense of release.”

But it really didn’t feel like this to us; somehow it felt much more mundane, much closer to the demi-monde described in the brilliant book ‘Edgelands’, populated by old cars, containers, landfill, sewage, rubble, wires, masts, pallets, power stations and industrial relics. Dare I say it, boring. But going under the M25 nonetheless gave us a sense of achievement, like climbing a minor peak.

Anyway, follow the River Lea all the way up to Ware; or at an earlier stage cut more easterly (turn right at the south side of the William Girling Reservoir, head through the cemetery and join the centenary walk) and head out through Epping Forest; the options are legion.

THE ROUTE

- Head out W through the new King’s Cross concourse into Battle Bridge Place. Head N with the German Gymnasium on your left and the oak tree and 1 Pancras Square on your right into Pancras Square

- Walk up to the top of the water features, then take a right (E) between the buildings back into King’s Boulevard; proceed N across Goods Way, then over the canal into Granary Square

- Walk round to the left of the Granary Building into Lewis Cubitt Square, then head N, across Handyside St alongside Lewis Cubitt Park, soon reaching the Skip Garden

- Turn right (SE) shortly after this into York Way and follow it down until you reach a path on your right just after Bingfield St heading south (there is a lot of building work here; if blocked stay on York Way until Handyside St, then turn right)

- Turn left on reaching Handyside St, then shortly right (S) into the linear Handyside Gardens, heading back towards the canal; as you approach the canal, bear left and go down steps onto the towpath going under York Way

- Now follow the towpath E until you have to leave the canal as it approaches the Islington Tunnel; on reaching Muriel St, turn right, then shortly left up a pedestrian route through a housing estate

- This pedestrian path takes you to Maygood Rd, at the end of which you turn right, then immediately left into Dewey Rd, which leads to Culpeper Park

- On reaching the other side of Culpeper Park, proceed E along Ritchie St, cross the Liverpool Rd into Bromfield St, then bear left into Berners Rd which leads into Upper St

- Turn left (NE) here and walk up to, then through Islington Green, turning right at the end by Waterstone’s

- Turn right (S) on meeting the Essex Rd, then shortly on your left you will spot Camden Passage, which you take; follow it until you reach Charlton Place

- Turn left down Charlton Place, and shortly turn right up some steps, then head through Colebrooke Row Gardens, then Duncan Terrace Gardens

- Take the first left (E) exit out of these gardens, cut back N up Colebrooke Row and then descend back to the canal towpath just north of Duncan St (make sure you walk on the canal path north of the canal, not the one to the south)

- Follow the canal E for just over 1 km, go under New North Rd, then climb steps on your left to join it (there is a new Royal Mail building on the S of the river just before this bridge

- Head S down New North Rd, then shortly head diagonally (SE) across Shoreditch Park, passing the big boulder; on reaching the enclosed adventure park area, head E along its north side and then SE through the Dorothy Thurtle Memorial Gardens

- Then head E along Ivy St, until reaching Hoxton St, where you will see the Hoxton Market arch to your left; turn R (S) down Hoxton St and you will soon reach the Hoxton Community Garden; head through it to the other side, then continue right down Hoxton St

- Turn left (E) at Shenfield St, and follow this (it is a path at one point) until you reach the main Kingsland Rd. Turn N here and you will soon arrive at the Geffrye Museum; enter through the main gate, visit if you have time, then exit at the north end back onto the Kingsland Rd

- Take the first right into Pearson St; first you will pass the Apples & Pears Adventure Park, then the charming St Mary’s Secret Garden, which merits a quick walk round; then continue east into the Arden Estate, reaching Weymouth Terrace and bearing left, through the Fellows Garden Square, then left (N) right into Kent St, heading E

- On reaching the main Queensbridge Rd, turn right, then shortly left across a zebra crossing alongside a high wall into Haggerston Park, heading due E

- As the path swings round to the S, take the Woodland Walk and then swing round the right of Hackney City Farm, turning left when you reach the main road to go past the main entrance

- You now head NE up Goldsmith’s Row, all the way over the canal, through Broadway Market and eventually reaching London Fields; take a look around, then make your way back past Broadway Market, re-joining the canal

- Follow the canal E until you reach the Canal Entrance to Victoria Park, which you enter; then take the track that keeps you parallel with the canal, heading towards the West Boating Lake

- Just before you reach the lake, take the smaller path heading off NE, called the Back Walk, around the northern edge of the lake, crossing the Grove Rd, and then bearing left (NE) to head directly past the bandstand along Central Drive, then passing the East Lake on your left

- Turn right through the Old English Garden, taking the path to the Model Boating Lake; then take the path heading NE to the east side of the park (Cadogan Gate) and you will see two alcoves in the distance, which you are heading for

- Turn right here (SE) and exit the park through St Mark’s Gate, soon joining the Hertford Union Canal and heading E again, past a lock and then crossing the canal S at the Roach Rd Bridge

- As you approach the end of Roach Rd, you will see an old chimney on your left and the Monier Rd footbridge over the River Lee Navigation, which you take

- Once over the bridge, follow the Lee Navigation Towpath north until just past the Copper Box arena

- Turn right (E) here along Cooper St, cross Eastcross Bridge over the River Lea and then bear left towards the Olympic Rings and the Velodrome; you will shortly reach the Timber Lodge Café, where the walk finishes.

PIT STOPS

Skip Garden Café, Tapper Walk, London N1C 4AQ (www.kingscross.co.uk/skip-garden, 10am-4pm Tue-Sat)

Towpath Café, 42 De Beauvoir Crescent, N1 5SB (towpathcafe.wordpress.com, 020 7254 7606). Highly recommended for its ambience, quirkiness and interesting food. A great place to watch the world of the canal go by.

Café Villa D’Aversa, 15 Broadway Market, London E8 4PH (07453 260003). We loved this café; bustling with intense and convivial conversations.

Frizzante, Hackney Park Farm, 1a Goldsmiths Row, E2 8QA (020 7739 2266, www.frizzantecafe.com) recently won a Time Out award for best family restaurant.

The Park Café in the Hub (left), The Hub Building, Victoria Park East, London E9 5HT. It’s unusual to find food inspired by a top Indian chef in a park café, but this bright, airy and spacious venue will change your views of both Indian food and the context in which it can be enjoyed.

The Park Café in the Hub (left), The Hub Building, Victoria Park East, London E9 5HT. It’s unusual to find food inspired by a top Indian chef in a park café, but this bright, airy and spacious venue will change your views of both Indian food and the context in which it can be enjoyed.

Counter Café, 7 Roach Road, Hackney Wick, E3 2PA (07834 275920, www.counterproductive.co.uk) A great vibe, very friendly and an unbeatable view across the water to the Olympic Stadium.

Unity Kitchen Café Timber Lodge, 1 Honour Lea Ave, Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, E20 1DY (020 7241 9076). I personally love the location and architecture of this building; some people like the food, others don’t, but it’s a great place to pause whilst looking around this massive park.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Camden Passage (N1 8EA); not as many antiques as there used to be, but lots of boutique shops and interesting finds.

Broadway Market (E8 4QJ). The market itself runs every Saturday; the area is full of quirky shops and services. You can find out more details at www.broadwaymarket.co.uk

Netil Market, 13 – 23 Westgate St, E8 3RL close to London Fields. A creative community of traders in arts, fashion and food, with a bar and Saturday stalls.

Hoxton Market (N1 6SH) and Street. The Market is open on Saturdays; quirky shops are open every day, including Hoxton St Monster Supplies, ‘purveyor of quality goods for monsters of every kind, established 1818’.

PLACES TO VISIT

London Canal Museum, 12 New Wharf Rd, 12-13 New Wharf Rd, N1 9RT (020 7713 0836, www.canalmuseum.org.uk) If you want to find out more about the history of the canal, then the canal museum, just south of the canal alongside Battlebridge Basin is worth a look. It is clearly signposted from the canal and is a five-minute walk. Open every day except Monday.

The Archivist, Unit V Reliance Wharf, 2-10 Hertford Road, N1 5ET. The Archivist programmes exhibitions and events all year round in a unique waterside exhibition space

Geffrye Museum, 136 Kingsland Rd, E2 8EA (020 7739 9893, www.geffrye–museum.org.uk), explores the home from 1600 to the present day. It also has period gardens and a herb garden. A charming and tranquil place.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Read: ‘Walking London’s Waterways’ by Gilly Cameron-Cooper, New Holland. A brilliant, detailed book p. 6 “Looking at London from the perspective of its waterways presents a different world, another level of existence away from the familiar sprawl of streets and arterial roads, shops, house and offices. Ribbons of almost-rural green wind by graceful willows and poplars. Here, sheltered from the roar of traffic and the pace of city life, kingfishers dart, herons stand and wild flowers flourish.”

Enjoy: ‘The Regent’s Canal’ by David Fathers, Francis Lincoln Publishers. Beautifully illustrated and stuffed full of interesting observations. One of my favourite books of all time.

Explore: Take an expert architectural tour with Open-City Engage – King’s Cross Renaissance or Olympics and Beyond

Read: ‘Edgelands’ by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, a brilliant polemic about those ‘familiar yet ignored spaces which are neither city nor countryside’.

Watch: East London from the Air, which includes Victoria Park, Regent’s Canal and London Fields.

Leave a Reply