So much perfection in a ‘hollow in the hills’

Bath is utterly unlike any other UK city, all planned perfection around a single glorious Georgian era of leisure and intrigue, with none of the ‘tattiness’ or ‘edginess’ you usually associate with British cities.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 9.5 km (5.9 miles); an extra 1.7kms (1.1 miles) if you add Beechen Cliff

- Height Change: 110 metres

- Typical time: 2 ½ hours (or 3 hours with Beechen Cliff)

- Start & finish: Bath Spa Station (BA1 1SU)

- Terrain: mainly pavements, but Bathwick Fields can be muddy

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Abbey Green, Kingston Parade, Queen Square, the Georgian Garden, Royal Victoria Park, The Botanical Gardens, Hedgemead Park, Parade Gardens, Henrietta Park, Sydney Gardens, Bathwick Fields, Smallcombe Cemetery, Beechen Cliff and Alexandra Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Avon, Kennet & Avon Canal |

| Stunning cityscape | Bath Abbey Tower, Lansdown Crescent, Bathwick Fields, Beechen Clif |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | The Roman Baths (60AD onwards), Bath Abbey (from the 12th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | South Parade & North Parade (1740s), Grand Pump Room (1790s), Queen Square (1728), Royal Crescent (1770s), The Circus (1750s), Lansdown Crescent (1780s); The Assembly Rooms (1769), Pulteney Bridge (1774); and of course most of the streets we walk through |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Bath Spa Station (1840), Bayntun’s Bookshop & Bindery (1901), St John’s Church (1863), Orange Grove Police Station (1865) |

| Industrial Heritage | Cleveland House, Sydney Wharf, Baird’s Maltings, Pumphouse Chimney, Thimble Mill Pumping Station (all early 19th C) |

| Modern (post-1918) | Thermae Bath Spa (2006), Extension to Holburne Museum (2011) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Pump Room Tea Room, Colonna & Smalls; Garden Café, Holburne Museum |

| Quirky Shopping | Milsom St, Green St, Walcot St, Farmers’ Market at Green Park Station |

| Places to visit | Roman Baths, Thermae Bath Spa, Jane Austen Centre, 1 Royal Crescent, Victoria Art Gallery, Holburne Museum |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Christmas Market (early December); Bath Literature Festival (early March); Bath International Music Festival (May/June) |

City population: 88,859 (2011 census)

Ranking: 80th largest city in the UK

Date of origin: Roman

‘Type’ of city: ‘Planned’ city

City status: Bath became a city by Royal Charter granted by Elizabeth I in 1590

Some famous inhabitants: Leo McKern (actor), Thomas Baldwin (architect), John Wood, the Elder and the Younger (architects), Thomas Gainsborough (painter), Sir Isaac Pitman (inventor of shorthand), Russell Howard (comedian), Beau Nash (master of ceremonies in Georgian Bath), Bill Bailey (comedian), Ken Loach (film director), Mary Berry (chef), Dr William Oliver (inventor of the Bath Oliver biscuit), William Pitt (Prime Minister), Jane Austen (novelist), Thomas Bowdler (expurgator of Shakespeare), Charles Dickens (novelist, frequent visitor to the city and set much of the Pickwick Papers in the city), Henry Fielding (novelist), Richard Sheridan (playwright), Mary Shelley (novelist, author of Frankenstein), Jacqueline Wilson (children’s author), Peter Gabriel (musician), Tears for Fears (pop group), Midge Ure (musician), Thomas Robert Malthus (philosopher and economist), Roger Bannister (athlete, first man to run sub-4-minute mile), Jeremy Guscott (rugby player), James Wolfe (general), Ralph Allen (postal pioneer & entrepreneur)

Notable city architects/planners: John Wood, the Elder (1704-1754) & The Younger (1728-1782); Thomas Baldwin (1750-1820)

Number of Listed Buildings: Bath and North East Somerset has 3,737 listed buildings, of which 131 are Grade I and 212 are Grade II*

Films/TV series shot here:

Les Miserables (2012) – Pulteney Bridge and Weir; The Duchess (2007) – The Assembly Rooms, Royal Crescent and Holburne Museum; Vanity Fair (2003) – Beauford Square, Great Pulteney Street, Holburne Museum and Sydney Place; Inspector Morse (1997) – Royal Crescent; Poldark (1995) – Abbey Churchyard; Bergerac (1991) – Theatre Royal; House of Elliot (1991-94) – Milsom Street, Theatre Royal, Royal Victoria Park, Assembly Rooms; Shoestring (1979) – Pump Room; The Wrong Box (1966) – Royal Crescent and St James’ Square; Miss Marple (1986) – Theatre Royal

CONTEXT

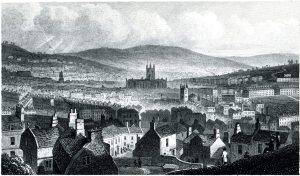

Bath has a striking setting in a ‘hollow of the hills’, with the River Avon running through its heart. From many vantage points on the surrounding hills you get excellent panoramas across the city; and from many points within the city, you can look straight out along a street and up into the countryside; always a great joy in a smaller city, a glimpse of the country beyond the urban landscape. Almost all the open land on slopes around the city is specially protected to retain the mixture of woodland and meadows, and this contributes greatly to Bath’s immense charm. And the city is small-scale: you can walk out of the city from Bath Abbey to Bathwick Meadows in little more than 15 minutes.

The city’s fame was assured by a unique natural asset: very hot water bubbling up from the ground as geothermal springs. The Romans built baths and a temple here. In the 17th century, claims were made for the curative properties of water from the springs, and Bath became famous as a spa town in the Georgian era.

Many of the Georgian streets and squares that gave Bath its unique architectural signature were laid out by John Wood, the Elder in the first part of the 18th-century. Much of the creamy gold Bath stone, a type of limestone used for construction in the city, was obtained from the Combe Down and Bathampton Down Mines owned by Ralph Allen. To advertise the quality of his quarried limestone, he commissioned the elder John Wood to build a country house on his Prior Park estate between the city and the mines. In the early 18th century, Bath became the most fashionable of the rapidly developing British spa towns, its social code developed by Master of Ceremonies Beau Nash, who presided over the city’s social life from 1705 until his death in 1761.

Unlike so many British cities, Bath is emphatically not a Victorian-inspired or Victorian-looking city. Whilst Bath barely doubled in size during the nineteenth century, neighbouring Bristol grew fivefold and became the dominant economic force in the region, whilst Bath’s fashionability faded.

In spring 1942, German air raids on Bath killed 400 people, destroyed 900 Georgian buildings, and damaged a further 12,500. These were part of the notorious ‘Baedeker Raids’, a series of attacks by the Luftwaffe on English cities. The towns targeted included Exeter, Canterbury, Norwich, York and Bath. The term had been coined by a spokesman for the German Foreign Office, who declared, “We shall go out and bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars in the Baedeker Guide”, a reference to the popular travel guides of that name.

Yet, devastating as these raids were, thoughtless post-war development probably harmed the fabric of the city far more. In the 1960s and early 1970s, some parts of Bath were unsympathetically redeveloped, resulting in the loss of many 18th- & 19th-century buildings. This process was largely halted by a popular campaign that drew strength from the publication of Adam Fergusson’s ‘The Sack of Bath’ in 1973.

In a talk he gave on the 40th anniversary of the book’s launch, he recounts: “I went there then as a journalist – fair-minded, non-judgmental, willing to hear all sides (like all journalists) – and returned as a crusader, profoundly shaken and motivated by what I had seen and heard. The bulldozers were still destroying huge stretches of what had been a complete Georgian town – not the grandest bits like the Baths and the Assembly Rooms where the visitors went, or the Crescents where they stayed, but, in their thousands, the little houses of the true 18th-century Bathonians. I am talking of the chair-carriers, the grooms, the buhl-cutters, the porters, the builders, the wig-makers, the shopkeepers; yes, and the pimps, pickpockets and prostitutes – all the people who lived full-time in that contemporary Las Vegas.

“Streets and streets of elegant little gems were disappearing under the lax preservation regulations of the time; and horrible new brutal developments were changing the character of the whole.”

“I am reminded of that scourge of Bath four decades ago – the assumed urban benefit of what they called “comprehensive development”. It was based on the premise, unchallenged by a cowed and confused city council, that only total destruction would allow the phoenix of an architectural Utopia to re-emerge from the flames. Of course, in time, this dismal creed was met by its diametrically opposite one – comprehensive conservation applied to and provided within a conservation area.”

“The Sack of Bath’s publication was the culmination of an already prolonged effort to lever the progressive destruction of Bath’s Georgian character into the popular consciousness. If it came too late to save much, it was in time to save a great deal more – and not only in one city.” And it is true, the book had a much wider effect than the purely local, challenging the orthodoxy of ‘comprehensive development’ in favour of restoring that which is good throughout the country.

And in 1987, the recognition and preservation of Bath’s glorious architectural heritage were confirmed when UNESCO awarded the whole city World Heritage Status – one of only two cities in the world to be designated in its entirety, the other being Venice.

Today, the city’s employment is driven by tourism and professional services. More than one million visitors stay and there are four million visits each year. It has become a fashionable ‘lifestyle haven’ for publishers, software programmers, lawyers and accountants. A poster at the railway station says it all: “First-class (legal) services without the London price tag.” I’m not sure potential home-owners would quite agree!

As a walker, the sheer volume of tourism makes it advisable to pick an out-of-season month to explore; or if your schedule brings you here in the summer, try to get out at the start or end of the day when the pavements are quieter and there is often some delightful early or late light striking the warm Bath stone.

THE WALK

The station is a fine piece of Brunel architecture (1840), but there’s no easy way of getting away from it with your perception of Bath all being Georgian intact. But maybe, on reflection that’s a good thing, as you then really get to appreciate later just how much has been preserved.

Worst of all, is the dreadful new SouthGate shopping centre on our left, large concrete retail boxes camouflaged less than successfully with mock-Georgian façades. Jonathan Glancey, writing in The Guardian, has its measure perfectly: “When you step out of the railway station, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, pretty much the first thing you see is a vulgar new shopping mall, dolled up in a style you might call Las Vegas Georgian for its soulless imitation. SouthGate’s new shops, which will give Bath a glut of the kind of chain stores and cafés you can find in any British city, are basically bulky concrete boxes pasted over with little more than a veneer of Bath stone. While these faux-Georgian frocks might look convincing in computer drawings, in reality the effect is crude and deeply disappointing.” The only positive to take away from it is that it replaced a 1960s shopping complex that apparently was even worse.

Manvers St slowly improves, with Bayntun’s Bookshop & Bindery (1901) and the Baptist Capel (Victorian Gothic) perhaps the most interesting. but the old police station further up on the right is certainly a shocker, and beyond it a car park.

But suddenly everything changes as we come out onto the Georgian excellence of South Parade, Duke St, North Parade and Pierrepont St. Almost all of these houses are Grade I listed, making it one of the highest concentration of Grade I buildings anywhere in the country. The streets were built in about 1743 by John Wood, the Elder (more about him a bit later).

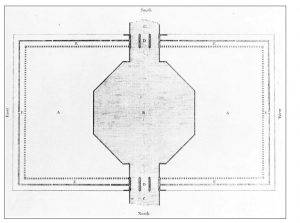

Grand as it is today, it is in fact only a fraction of a still grander vision for a Royal Forum . Even while the Parades were being built, Wood had enlarged his plan to an enormous rectangle, 1,040 feet long (EW) by 624 feet broad (NS), exactly bisected by the Avon and centred upon ‘an Octangular Bason of Water’ where the river was widened out to create ‘the Haven of BATH’. On each side of the river were to be wide Piazzas ‘for People to celebrate their Feasts and Festivals, and carry on their Commerce’. Two bridges were to link the piazzas, one built on the line of the present South Parade where it now ends, high above the river. Arched recesses or porticoes were to be built around all four sides of the vast rectangle, above which would be ‘Terrasses of fifty feet broad, before four lines of Building, intended to be erected in a Rich and Elegant Manner’. It was to be a complete escape from the narrow streets of the old city to classical order and logic. ‘Bath’, Wood says, ‘will appear much the same that Virgil declares Carthage to have appeared to Aeneas’. But it was never to be, due to lack of funding, a familiar woe of grand urban planning.

. Even while the Parades were being built, Wood had enlarged his plan to an enormous rectangle, 1,040 feet long (EW) by 624 feet broad (NS), exactly bisected by the Avon and centred upon ‘an Octangular Bason of Water’ where the river was widened out to create ‘the Haven of BATH’. On each side of the river were to be wide Piazzas ‘for People to celebrate their Feasts and Festivals, and carry on their Commerce’. Two bridges were to link the piazzas, one built on the line of the present South Parade where it now ends, high above the river. Arched recesses or porticoes were to be built around all four sides of the vast rectangle, above which would be ‘Terrasses of fifty feet broad, before four lines of Building, intended to be erected in a Rich and Elegant Manner’. It was to be a complete escape from the narrow streets of the old city to classical order and logic. ‘Bath’, Wood says, ‘will appear much the same that Virgil declares Carthage to have appeared to Aeneas’. But it was never to be, due to lack of funding, a familiar woe of grand urban planning.

St John’s Catholic Church was designed and built between 1861-3 by Charles Francis Hansom, who was the brother of J. A. Hansom, the creator of the Hansom cab. They are often quoted as being the second best Roman Catholic architects of their day, for their success in picking up commissions that the more famous Augustus Pugin had passed over. Nikolaus Pevsner rather amusingly suggests St John’s is “demonstrative proof of how intensely the Gothicists hated the Georgians of Bath”. I enjoy its somewhat out of placeness in a predominantly Georgian city.

Abbey Green is a beautiful cobbled square with a very mature tree in the middle of it that looks a little big for the space, but therein lies its attraction.

Abbey Green is a reminder that there was a thriving city before Georgian Bath, which the Georgians were more than happy to cover over (literally). The houses that you see all look Georgian, but in fact are Georgian façades hiding much older, medieval buildings. A casual glance at 2 Abbey Green and you would think it mid-Georgian. But a renovation uncovered stone mullioned windows in the side wall. So maybe the Georgian façades of SouthGate shopping centre are just another phase of a long architectural tradition?!

And now we have reached the slightly drab Kingston Parade (no greenery). But I guess on the plus side it means it’s easy to install market stalls and have street performers, shows, so I’m probably being unfair.

The Roman Baths complex has gone through several historic phases. The hot springs were first discovered by the Celts. The Romans constructed a temple to Sulis on the site in 60-70 AD and the bathing complex was gradually built up over the next 300 years. The Roman Baths themselves are now below the current street level and the spring is housed in 18th-century buildings, designed by architects John Wood, the Elder & Younger. The visitor entrance today is via the 1897 concert hall by J M Brydon. The hot springs are the cornerstone of Bath’s draw – first attracting the Romans, then genteel Georgian society and now hordes of tourists.

But since the late 1970s, the water that flows through the Roman Baths has not been considered safe for bathing. The newly constructed Thermae Bath Spa 200 metres to the west, designed by Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners, and the refurbished Cross Bath, allow modern-day bathers to experience the waters via a series of more recently drilled boreholes. A swim in the open-air rooftop pool is thoroughly recommended – a simultaneous sense of removal from the life of the city and of a renewed connection with the hills that encircle it.

Bath Abbey was a former Benedictine monastery, founded in the 7th century. It was rebuilt in the 12th and 16th centuries, and major restoration work was carried out by Sir George Gilbert Scott in the 1860s. It is one of the best examples of Perpendicular Gothic architecture in the region, with a particularly fine vault ceiling.

The Grand Pump Room, built by Thomas Baldwin, was the epicentre of Bath’s social scene at the start of the nineteenth century. In Jane Austen’s words, “Every creature in Bath was to be seen in the room at different periods of the fashionable hours”. On arrival in the city, you were expected to write your name, address and the length of your stay in “The Register”. Everything ‘Society’ needed to know about you could be gleaned from these inputs, an early version of Facebook really.

And Richard ‘Beau’ Nash (1674-1762), was its impresario. He came to Bath in 1703 as an aide de camp to the Master of Ceremonies, Captain Webster. The young Richard Nash took his place when the Captain was killed in a duel. He then set about changing the social behaviour of the citizens, creating a strict code of etiquette which became the norm for all walks of life, and made the city a pleasanter and safer place. He became the ‘Arbiter of Elegance’ and was known as the ‘King of Bath’. He would meet new arrivals and judge whether they were suitable to join the select company of 500 to 600 people who had pre-booked tables, match ladies with appropriate dancing partners at each ball, pay the musicians at such events, broker marriages, escort unaccompanied wives and regulate gambling.

He lived with his mistress, Juliana Popjoy, in a fine house, which is now the Theatre Royal in Sawclose (which we go past next) and maintained his luxurious mode of living by gambling until gaming was outlawed in 1745. Nash died a pauper (being an inveterate gambler himself) but was buried in Bath Abbey.

Queen Square is the first element in “the most important architectural sequence in Bath”, which includes the Circus and the Royal Crescent. It was the first speculative development by the architect John Wood, the Elder, who later lived in a house on the south side of the square, apparently with the best view (builders always seem to wangle the best house!). “It was in keeping with Wood’s robust sense of self-satisfaction that he should have made his home in… the central house of the …south side. There he could enjoy, on an axial line, his Egyptian obelisk and the 23-bay palace of the north side.”

Wood set out to restore Bath to what he believed was its former ancient glory as one of the most important and significant cities in Britain. In 1725 he had developed an ambitious plan for his hometown, a vision of building the “Rome of the North”: “I proposed to make a grand place of assembly, to be called the Royal Forum of Bath; another place, no less magnificent, for the exhibition of sports, to be called the Grand Circus; and a third place, of equal state with either of the former, for the practice of medicinal exercises, to be called the Imperial Gymnasium of the City, from a work of that kind, taking its rise at first in Bath, during the time of the Roman emperors.”

He understood that polite society enjoyed parading, and in order to do that Wood provided wide streets, with raised pavements, and a thoughtfully designed central garden in Queen Square. The formal garden was laid out with gravel pathways, low planting and was originally enclosed by a stone balustrade.

The obelisk in the centre of the square was erected by Beau Nash in 1738 in honour of Frederick, Prince of Wales. It formerly rose from a circular pool to a point 70 feet high, but a severe gale in 1815 truncated it.

25 Gay Street was briefly Jane Austen’s home, and we walked past the Jane Austen Centre at 40 Gay St, in a house similar to the one she lived in. It gets mixed reviews on TripAdvisor, a reminder perhaps that almost everyone tends to have a strong view about Jane Austen. I rather like Andrew Swift’s description of her as the ‘tutelary deity of Bath’s tourist industry’. I will leave you to make up your own mind.

Instead of going to the Circus at this point (which would perhaps be more logical if you want to explore the architectural development chronologically), we couldn’t resist taking The Gravel Walk; this was the secluded, gently rising walk that Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot of Persuasion took when they were finally reconciled. And it’s not too fanciful to say, it has a ’peace’ and auspiciousness’ about it that promotes calm and harmony.

The Georgian Garden, to the rear of Number 4, The Circus, with access from the Gravel Walk as the path starts swinging to the left is, courtesy of an excavation and careful recreation, a rare example of how a Georgian garden would have looked.

At the beginning of the 18th century, townhouses often had nothing by way of a garden but a simple paved yard; but by the advent of the early 19th century a walled garden, home to flowers and shrubs, was to be found at the rear of the terraced homes of the well to do. It provided a private, decorative space for the occupier of the house. It was a very formal design, without any grass and was mostly covered with a surface of gravel mixed with clay. In a way, more like the style of back garden many townhouses are reverting to today, more of an ‘outside room’ for social interaction.

As we swung round into the expanse of the meadow, we appreciated that the Gravel Walk is also the best way of coming upon the Royal Crescent, getting that first memorable glimpse from a ‘countryside’ setting, in much the same way as would have been intended – whereas his dad designed great urban landscapes, John Wood the Younger, who designed it, really created something of the ‘country in the city’ with the Royal Crescent, symbolised by the ‘ha-ha’ wall typically associated with country houses, protecting the controlled order of the house from the untamed nature beyond the wall (and perhaps more practically stopping the sheep pooing on the lawn).

And, yes, you are thinking of the correct derivation of ‘ha ha’ – it’s called that simply because it makes you laugh when you experience it. The erudite Horace Walpole recorded that the name is derived from the response of ordinary folk to encountering them and that they were “… then deemed so astonished, that the common people called them Ha! Has! to express their surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to their walk.”

The Royal Crescent took our breath away, the epitome of architectural beauty. Built between 1767 and 1774, it has the ‘definitive’ Georgian crescent feel and does it better than anywhere else. But all is not what it seems; while Wood designed the great curved façade of what appear to be about 30 houses with Ionic columns on a rusticated ground floor, that was the extent of his input. Each purchaser then bought a certain length of the façade, and employed their own architect to build a house to their own specifications behind it; hence what appears to be two houses is sometimes one. This becomes evident when you look at the rear of the crescent: while the front is completely uniform and symmetrical, the rear is a mixture of differing roof heights, juxtapositions and fenestration. This “Queen Anne fronts and Mary-Anne backs” architecture occurs repeatedly in Bath (on Lansdown Crescent, for example, which we pass a little later).

In the 1970s the resident of No 22, Miss Wellesley-Colley, painted her front door yellow instead of the traditional white. Bath City Council issued a notice insisting it should be repainted. A court case ensued that resulted in the Secretary of State for the Environment declaring that the door could remain yellow. And therein lies the eternal debate. Should Bath be left in aspic, or should it be allowed to develop where appropriate? It’s reassuring to note that when we checked out the colour of no. 22, it is still yellow. Is it now frozen in its own 70s aspic?!

Royal Victoria Park (23 hectares, 57 acres), which we come to next, is a beautiful expanse of green parkland. Originally an arboretum, the park dates back to 1829 and is named after Queen Victoria, who officially opened it in 1830 at the age of 11. Victoria never returned to Bath. During her visit, it is said that a local resident commented on the thickness of her ankles. The observation was duly reported to the Princess, causing her to shun the City for the duration of her reign. The only time she passed through again was by train from Bristol to London, when she reportedly kept the blinds in her carriage firmly drawn.

Bath didn’t quite give up on Victoria, though. The three-sided Obelisk of the Victoria Majority Monument was erected in 1837 to honour the Princess’s eighteenth birthday. The monument bears her portrait.

The Botanical Gardens were formed in the north-west area of the park in 1887. They contain a fine collection of plants that thrive on limestone, the same strata that are so amenable to the hot springs. The replica of a Roman Temple in the gardens was used at the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley in 1924. And to the north of the Botanical Gardens is the Great Dell, a sunken wooded area alongside Weston Road. It is a former stone quarry planted out in the 1840s with a collection of unusual trees, including some large North American conifers.

St James’s Square, which we glimpsed down to the right as we headed up Park St, consists of 45 Grade I listed buildings. It was built in 1793 by John Palmer and is the only complete Georgian square in Bath, escaping any wartime bombing or subsequent re-development.

Jane Austen may have taken this very same sneaky route up Park St to avoid the throngs, as she loved walking to relax and have time on her own. She writes about her Bath walks often in her letters, notably to Lansdown (the route we are taking), Charlecombe, Twerton and Widcombe: “The pleasure of walking and breathing fresh air is enough for me, and in fine weather, I am out more than half my time.”

We were so pleased with our little ‘snicket’ up the hill as it comes out in front of the stupendous Lansdown Crescent, well away from the throngs of tourists at last. The crescent was laid out in the late 1780s by John Palmer, who ensured that the three-storey fronts of the buildings were of a uniform height and had matching doors and windows. The attic rooms are under a parapet and slate mansard roof. Other builders were then able to construct the houses behind the façade, in much the same way as The Royal Crescent.

There is war damage of sorts here too, though at first, it doesn’t meet the eye. The crescent sacrificed its metal finials for the war effort. All around the country, cast-iron railings from squares and homes were requisitioned. The great sadness is that the iron turned out to be unsuitable for munitions and was generally left on scrap heaps to rust away (in my hometown, Stamford, for example, it was left on the meadows for a generation before finally being cleared away).

Anyway, this being Bath, a heritage-obsessed owner worked tirelessly for years to persuade all her neighbours that the finials needed to be replaced and finally got some funding too. She told a national newspaper: “Most people don’t notice when they first move in. It takes about five years before you realise that some railings have finials and some don’t. I had to persuade the occupants of every house in the crescent that it was worth doing and worth paying for. It comes from my passion for heritage.”

The sheep spending part of the year in the field beneath the crescent belong to farmer Douglas Creed from Kelston. He began using the field in the early 1990s, so is very familiar with the practicalities of the site. Apparently, he prefers to mate his sheep relatively late so that lambs are born after the worst of the winter is over. He also needs to wait until the lambs are of sufficient size not to be able to squeeze through the railings into Lansdown Crescent and face danger from passing traffic.

Lansdown Crescent clearly has a very committed neighbours’ group. You can get a feeling of a better, gentler world where neighbours look out for each other, stray sheep are returned to their proper place and all major national occasions are celebrated with a jolly good street (crescent) party, by visiting their website at http://www.lansdown-crescent.org.uk/association.shtml

Cutting across east we next arrived at the steep Hedgemead Park (2 hectares, 5 acres). Unusually for a park, it came about by an accident rather than by years of community petitioning, when in 1889 the houses below Camden Crescent collapsed due to a landslide. The layout of the paths and terrain were engineered to prevent the possibility of future landslides.

Then we cut back into the centre of Bath and took a quick peek at The Circus before returning via The Assembly Rooms. John Wood, the Elder, convinced that Bath had been the principal centre of Druid activity in Britain, surveyed Stonehenge and used the same dimensions (318 feet) for The Circus’ diameter.

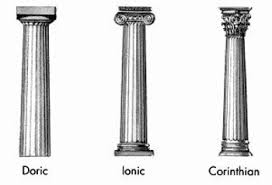

The Circus consists of three long, curved terraces designed to form a circular space or theatre intended for civic functions and games. The games give a clue to the design, the inspiration behind which was the Colosseum in Rome. Like the Colosseum, the three façades have a different order of architecture on each floor: Doric on the ground level, then Ionic on the middle floor (piano nobile), and finishing with Corinthian on the upper floor, the style of the building thus becoming progressively more ornate as it rises.

Between 1758 and 1774 number 17 The Circus was home to Thomas Gainsborough and used as his portrait studio. Being located in Bath enabled him to attract a fashionable clientele and he became the leading British portraitist of the second half of the 18th century. Gainsborough, while charming to his sitters, was often frustrated by ‘the curs’d Face Business’, as he referred to portrait painting in letters. His true passion was landscapes, but they never sold as well.

The Assembly Rooms, designed by John Wood the Younger in 1769, formed the hub of fashionable Georgian society in the city, the venue being described as ‘the most noble and elegant of any in the kingdom’. People would gather in the rooms in the evening for balls and other public functions, or simply to play cards. Mothers and chaperones bringing their daughters to Bath for the social season, hoping to marry them off to a suitable husband, would take their charge to such events where one might meet all the eligible men currently in the City. During the season, which ran from October to June, at least two balls a week were held, in addition to a range of concerts and other events. Jane Austen wrote about it in Northanger Abbey: “Mrs Allen was so long in dressing, that they did not enter the ball-room till late. The season was full, the room crowded, and the two ladies squeezed in as well as they could. As for Mr Allen, he repaired directly to the card-room, and left them to enjoy a mob by themselves.”

St Andrew’s Terrace cut through – I love these little passages, and there is quite a famous bakery school there should you get detained, so typical of the ‘Bath Lifestyle’ – a lifestyle which is the most evident of any city we have visited on our urban rambles. The Bertinet Bakery and Cookery School invites you to “sign up for one of our fantastic autumn classes and learn a new skill in breadmaking, patisserie, pasta, chocolate and much more” at http://www.thebertinetkitchen.com/

Milsom St is full of indie shops and often gets shortlisted as one of the best shopping streets in the country. Its popularity goes way back, being mentioned by Jane Austen in Persuasion: “Walking up Milson St, she had the good fortune to meet with the Admiral. He was standing by himself, at a print shop window….’I can never get by this shop without stopping’.” there is also a passage in the book set in the fashionable sweetshop Mollands, at No. 2.

The Corridor is one of the oldest shopping malls in the country. Designed by Henry Edmund Goodridge, it opened in 1825. Customers were originally serenaded in galleries overhead, which are still there, a touch up from piped music methinks. It has perhaps seen better days shopping-wise but makes an interesting cut-through. And then we came out in front of The Guildhall, built in the 1770s by Thomas Baldwin. The central dome was added in 1893. It forms a continuous building with the Victoria Art Gallery and the covered market.

Bath Guildhall Market is located behind the Guildhall and can be accessed by its own entrance tunnel through the Guildhall. It has traded on this site for the last 800 years. About 20 stall holders trade there nowadays.

Guildhall Market by www.valeriepirlot.com

Orange Grove Police Station. Built in 1865 by Charles Edward Davis, this fine building saw active service until 1966 when a new headquarters was constructed in Manvers Street (now a university building). It was converted into a restaurant in 1998. The prison cells are now the lavatories.

Parade Gardens (1 hectare, 2.5 acres) is worth visiting for the views across the river and especially the view upstream to Pulteney Bridge. If you like good traditional bedding in your parks then this is the place for you in season as it has one of the best displays in the country which, in 2013 was a Gold award winner in the RHS Britain in Bloom competition. The bandstand is that rare thing, not-Georgian, that little-known Bath architectural style. In fact, it dates back to 1925, replacing an earlier nineteenth-century bandstand.

There is a charge of £1.50 to enter, which is unusual for a public park. Initiated in the first part of the eighteenth century by Richard ‘Beau’ Nash, admission to these gardens was always by subscription, ensuring exclusivity; but that doesn’t go down so well in today’s more egalitarian world! The charge meets with considerable opprobrium on TripAdvisor.

The large building overlooking the Parade Gardens from Grand Parade is The Empire, built in 1898 as a hotel. The interesting rooftop, depicting cottages, a townhouse, a manor house with Dutch-style gable and a castle is said to have represented the different classes of Victorian customer who were all welcome to use the hotel!

The large building overlooking the Parade Gardens from Grand Parade is The Empire, built in 1898 as a hotel. The interesting rooftop, depicting cottages, a townhouse, a manor house with Dutch-style gable and a castle is said to have represented the different classes of Victorian customer who were all welcome to use the hotel!

Pulteney Bridge is one of the iconic landmarks of Bath. It was completed in 1774 and was built to connect the city to the new Georgian town of Bathwick. Designed by Robert Adam in a Palladian style, it is exceptional in having shops built across its full span on both sides.

Laura Place is named after Henrietta Laura Pulteney, daughter of Sir William Johnstone Pulteney and Frances Johnstone Pulteney, who owned the Bathwick Estate, which comprises four streets joined on the diagonals of Laura Place: Argyle Street, Henrietta Street, Johnstone Street and Great Pulteney Street. It is described by Pevsner as “one of the most impressive of all Neoclassical urban set pieces in Britain”. High praise indeed, to be compared with the likes of New Town in Edinburgh and Grainger Town in Newcastle.

Then we headed left and up through the rather beautiful Henrietta Park (2.8 hectares, 7 acres), much quieter than the Parade Gardens and of course free. The park was laid out to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria of 1897 (it seems they didn’t give up on her, although she had on them…). The Garden of Remembrance is a particularly tranquil spot to enjoy.

On your left, as you face the Holburne Museum and Sydney Gardens, you will see another of Jane Austen’s Bath homes at 4 Sydney Place. No wonder she didn’t feel very settled in Bath; in the five years she lived here from 1801-1806 she stayed at four addresses, although this one was where she spent the longest – 3 years. She wrote of it: “It would be pleasant to be near the Sydney Gardens. We could go into the Labyrinth every day.” Today the house is called Jane Austen’s Apartments and, if you are a Janeite, you can rent out Emma’s Garden Apartment, Cassandra’s 1st floor Apartment, or Mr Darcy’s 2nd floor Apartment if you are feeling a little racier; and dangerously close, methinks, to Lizzie Bennett’s Penthouse Apartment one floor up floor with ‘a master bedroom with a king size bed which sleeps two and can also be twinned’.

Sydney Gardens (4 hectares, 9.9 acres) were constructed in the 1790s as a commercial pleasure grounds, in the tradition of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens that were such a feature of society life in London in the late 18th century.

The Sydney Hotel (now the Holburne Museum), was built in 1796 as a casino and gateway to the pleasure gardens. It was entered through archways that took you first into a foyer and then through gauze curtains decorated with Apollo strumming his lyre, into a landscape of pure pleasure. Musicians played on the terrace above so that the visitor entered a magical scene of supper boxes, entertainments, masques, follies and numerous places of assignation.

The gardens themselves included a labyrinth, grotto, sham castle and an artificial rural scene with moving figures powered by a clockwork mechanism. They were illuminated by over 15,000 ‘variegated lamps’. The gardens were conceived as an exclusive meeting place for the nobility and gentry who, for a season’s subscription of about eight shillings, would be given brass admission tokens embossed with a picture of the garden. The gardens were used daily for promenades and public breakfasts and naturally, Jane Austen was a regular visitor.

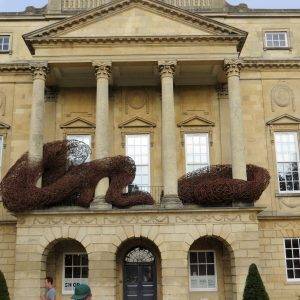

Now, what’s perhaps most surprising about the Holburne Museum is not its original age (late 1790s, so safely Georgian) but that it has a striking modern glass extension at the back, where the café is situated. Eric Parry, the extension’s architect, described how the project ‘unleashed violent and surreal feelings’ amongst the many who were deeply anti anything not-Georgian. But it’s telling that in its first year of re-opening, the museum’s footfall apparently increased by 500%!

In a talk that Eric Parry gave subsequently, he felt able to put a more positive spin on the outcome: “What the people of Bath clearly recognise is the need for more joie de vivre in the city’s architecture to keep its heritage alive. The focus should not be on the origin of architects, but how to find the best contemporary talent (and there is plenty), in order to return Bath to the place of celebration that it was originally designed as.” The original Sydney Gardens certainly epitomised this pleasure, as did the number of people spilling out of the café into the garden, chatting animatedly as we sauntered past.

The Kennet and Avon Canal passes through the gardens via two short tunnels and under two cast iron footbridges dating from 1800. There is also an iron footbridge over the railway which was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and built in 1840, as were the retaining walls. Even the public conveniences are listed buildings.

Cleveland House is one of the treasures of the Kennet & Avon Canal. Built by the Duke of Cleveland as the headquarters for the canal company, it is claimed to be one of the first purpose-built office blocks in Europe. Unusually, it is built half on land and half over the canal, and had a magnificent two-storey boardroom over the canal. A trap-door in the tunnel roof was used to pass paperwork between clerks above and bargees below.

Sydney Wharf has been a busy wharf for many years. Coal from the Somerset Coalfield was unloaded here, as were slates and agricultural products. Fly boats left from here as well – fast boats pulled by teams of horses. Today you can hire boats from the wharf. Baird’s Maltings was a malt house beside the canal. Grain was soaked in water, then sprouted and dried to produce malt to make beer. At the top of the buildings opposite the towpath, you can still see ‘Hugh Baird & Sons Maltsters’ painted in white on the end wall, beside the conical malt house chimney.

Canals provide a ‘nature’ corridor through cities. David Goode, in his famous book ‘Nature in Towns and Cities’, writes this about the Kennet & Avon canal as it winds its way through Bath : “The leaky lock gates are colonised by a tangle of water-loving plants including gypsywort, skullcap, pendulous sedge and wild angelica, with a profusion of liverworts covering the woodwork at the lower levels. Hart’s tongue fern, wall daisy and pellitory-of-the-wall grow on the lock walls, whilst the towpath edge has white dead nettle, shepherd’s purse, knotweed, nipplewort, herb Robert, soapwort and hedgerow cranesbill. Winter heliotrope and tansy cover the canal banks in places and in autumn the tangled hedges are festooned with old man’s beard, snowberry and arboreal ivy. Herons, kingfishers and dabchicks regularly fish where it broadens out for boats to turn. One heron, oblivious to passersby, has learnt to wait patiently by the lock gates where it catches small fish carried through the leaky gates.”

Top Lock is close to the lockkeeper’s cottage where, in former times, the lock keeper lived. Top Lock Cottage was also known as the barter store, as goods were traded between boaters. More Ecanal rather Ebay you might say.

Top Lock is close to the lockkeeper’s cottage where, in former times, the lock keeper lived. Top Lock Cottage was also known as the barter store, as goods were traded between boaters. More Ecanal rather Ebay you might say.

It is thanks to the diligence of Sydney Buildings’ residents that we know so much of this community’s history, as they have meticulously researched and written about it, sharing their findings on www.sydneybuildingshistory.org.uk. The development of the road was determined by two factors: the opening of the Kennet & Avon Canal and the residential development of the Bathwick area. And just to show that community spirit is alive and well and probably stronger in Bath than anywhere else, just take a look at this ‘bonkers’ YouTube about re-painting the lampposts in the street, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkNdArFnhDA .

The National Trust acquired Bathwick Fields in 1984 with funds raised by the Council and local people keen to see this meadowland preserved. From the top field, we got a truly iconic view across Bath, from Beechen Cliff on our left to Lansdown Hill on the right; this being the third part of the triangle, taking in views that have defined Bath since Georgian times.

In 1856 the Smallcombe Cemetery, just south of Bathwick Fields, was opened. Population expansion had seen the Parish of Bathwick overwhelmed by demands for burials outside the city. At only £3, a ‘decent burial’ was affordable by most, so, as well as the aristocrats and military figures, it is the artisans, craftsmen and artists who built and traded in Victorian Bath who are buried here. In many ways, the type of people whose houses may have been knocked down in the ‘Sack of Bath’…

Smallcombe remains the semi-wild, tranquil garden described in 1856 as ‘secluded and even picturesque, a beautiful spot, commanding a fine view of the city’. The cemetery has two chapels; the Anglican, dating from 1855 by Thomas Fuller, which has a fine porch; the Non-Conformist built in 1861 has a pleasing octagonal design and is by Alfred Goodridge. And the good news is that The Smallcombe Garden Cemetery Conservation and Heritage Project has recently been awarded a grant by the Heritage Lottery Fund to support a two-year conservation project to ensure that a hidden social, historical and ecological gem doesn’t become lost to neglect and decay.

Anyway, back to the delights of the canal. Pumphouse Chimney was built in an ornate style as the wealthy residents on Bathwick Hill did not want to overlook an industrial style chimney (how very Bath…). Specialist stonemasons restored the 30ft carved stone chimney in 2011, carefully replicating the two-degree lean that the chimney had developed since its construction in the 1840s.

Wash House Lock has an elegant iron footbridge crossing the canal. Apparently, the lock gets its name from the washing that local women did for wealthy visitors who came to Bath for the Season. Thimble Mill Pumping Station was vital to the working of the canal as it pumped water up from the river, replacing the water that was lost each time a boat went through the locks.

And then back over Halfpenny (Widcombe) Bridge. An earlier, wooden version of this footbridge had collapsed, tumbling dozens of people into the river. It was re-built in metal in the late 1870s and charged a halfpenny toll to recoup the building costs, hence its name. But don’t worry, you won’t need a halfpenny these days, and the structure looks robust. You will soon be delivered back safely to Bath Spa where our journey began.

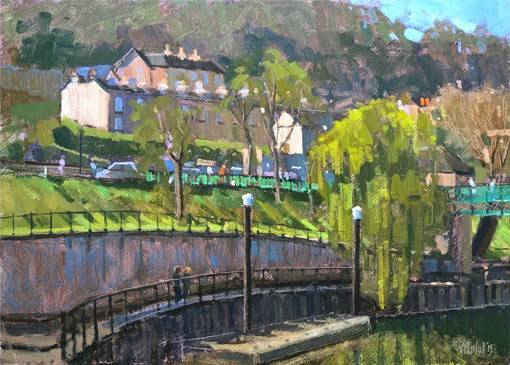

Widcombe Footbridge by www.valeriepirlot.com

Additional loop to Beechen Cliff (an extra 1.7km, 1.1 miles)

As a final way of exhausting ourselves, we climbed up Jacob’s Ladder (a series of steep steps) to Beechen Cliff and Alexandra Park (4.5 hectares, 11 acres) to get the view of the city from a 100-metre vantage point. This is a great place to first see Bath from, as the great architect of the city John Wood the Elder noted back in 1742: “For the eye to distinguish the buildings of the city…such as would view them more distinctly must ascend to the summit of Beaching Cliff, looking down from which, Bath will appear to them much the same that Virgil declares Carthage to have appeared to Aeneas.”

As a final way of exhausting ourselves, we climbed up Jacob’s Ladder (a series of steep steps) to Beechen Cliff and Alexandra Park (4.5 hectares, 11 acres) to get the view of the city from a 100-metre vantage point. This is a great place to first see Bath from, as the great architect of the city John Wood the Elder noted back in 1742: “For the eye to distinguish the buildings of the city…such as would view them more distinctly must ascend to the summit of Beaching Cliff, looking down from which, Bath will appear to them much the same that Virgil declares Carthage to have appeared to Aeneas.”

THE ROUTE

- Coming out of the station, head due N up Manvers St, turning right into South Parade, then left up the pedestrian Duke St to North Parade

- Turn left here (W), crossing Pierrepont St, staying on the left side to head down North Parade Passage

- On reaching Abbey Green, bear right at the far side up Abbey St to Kingston Parade; and walk between the Roman Baths (on your left) and Bath Abbey (on your right)

- Turn left (W) into the Abbey Church Yard, under a colonnade, turn right into Stall St, then left into Westgate, heading to Seven Dials at the end, then head N up Saw Close and Barton St; then first R into Trim St, first left under the arch into Queen St and then the second L into Wood St to reach Queen Square

- Cross over to the NE side of Queen Sq into Gay St, then turn left at Queen’s Parade Place and immediately right up some steps into the Gravel Walk along Royal Victoria Park; follow this as it bears round to the left, with the glorious vista of The Royal Crescent on your right

- Cross Marlborough Lane, heading due W past Victoria’s Column, and turn right into the park in front of the Fish Pond

- Explore the Botanical Gardens, then head along the path NE that reaches the Weston Rd at Cotswold Way; cross here and continue the path in a NE direction until it reaches Cavendish Rd

- Cross into Park Place, then take the first left up Park St, at the end of which you take a little footpath that takes you up to All Saints’ Rd

- Turn right at Lansdowne Place, and then follow the Crescent as it swings east then south until it reaches the Lansdown Rd

- Head down Lansdown Rd and take the first left into Lansdown Grove, at the end of which you turn right into St Stephen’s Rd; as the road twists to the left, take the path straight ahead that takes you into Camden Row

- At the bottom, turn left and take the second left down the tiny Hedgemead Rd

- Shortly on your right, take the steps leading down into Hedgemead Park; head S through the park to the exit in Lansdown Rd

- Cross the pedestrian crossing and head W up Brunswick Place; take the first left into Rivers St, then left again into Russell St, at the end of which you see the Assembly Rooms

- Turn right into Bennett St, take a loop around The Circus, return to Bennett St and then take the right just in front of the Assembly Rooms down St Andrew’s Terrace; kinking right, then left until it reaches George St

- Head left here, then right (S) down Milsom St, following it down into the pedestrianised Burton St (the left of the two streets), which then reaches Upper Borough Walls; cross over into the pedestrianised Union St, then take the second left along ‘The Corridor’, eventually coming out into the High St

- Turn right down Orange Street, swinging left to Parade Gardens by the river. Then head left (N) along Grand Parade and across Pulteney Bridge, along Argyle St; then left at Laura Place into Henrietta St and, as it swings around to the right, into Henrietta Park

- Cross E across the park into Sutton St, crossing Sydney Place, then entering Sydney Gardens via the Holburne Museum (or to the right)

- Cross Sydney Gardens over the railway bridge and then S along the Kennet & Avon Canal, crossing to the E side just after Cleveland House; then follow is S along the towpath to Bathwick Bridge, where you come off the towpath, cross the bridge and follow the towpath on the west bank instead

- At Lock 13 cross the canal footbridge, then go W up slope/steps to Sydney Buildings. Cross the road, walk up two flights of steps and continue on the path into Bathwick Fields

- Head up Bathwick Fields in a SW direction and resist the temptation to look back too early; through one hedge into Richens Orchard and then another, bringing you to a track heading S

- Turn right(S) here along the track, past Smallcombe Farm on your left, then reaching Smallcombe Cemetery (also known as Bathwick Cemetery)

- From the cemetery, head along the tarmacked track NW to re-meet Horseshoe Walk, which you then turn down left to walk back down to the canal

- Return to the canal path and head E all the way to Bath Deep Lock and the terminus of the canal

- Cross the Pulteney Rd bridge, turn left down some steps and continue following the canal towpath on the S side until it joins the river; turn left here up into Rossiter Rd, then shortly right back across Halfpenny Bridge, turn left through the tunnel and you are back at the station!

Additional loop to Beechen Cliff (an extra 1.7km, 1.1 miles)

- Instead of heading across Halfpenny Bridge, cross left over the A36 by the pedestrian crossing, turn slightly right on the other side then up Lyncombe Hill

- Take the first right into Calton Rd, then very shortly take the Jacobs Steps on your left heading steeply up, across Alexandra Rd, swinging right at the top and reaching Alexandra Park & Beechen Cliff

- Walk W along Alexandra Park, and then just to the north of a row of houses along a footpath

- Eventually, the path reaches Holloway Rd, where you turn right heading back down towards the river; when the road swings around to the right, take the path straight ahead down to the to the mega roundabout; take the underpass to the north side, then a bridge back over the river to the bus station. Turn right here back to the train station.

PIT STOPS

Pump Room Tea Room, Abbey Chambers, Church St, BA1 1LZ (01225 444477, www.romanbaths.co.uk/pump-room-restaurant ) for the quintessential Georgian English afternoon tea experience

Colonna & Smalls, 6 Chapel Row, BA1 1HN, just off Queen Sq (07766 808067, www.colonnaandsmalls.co.uk) if you like a hip, minimalist style, this is for you, just the opposite of the Pump Room in fact. In their words: “Our shop is all about exploring the flavour of coffee, focusing on how region, variety, processing, roast and brew method affect the taste.”

Parade Gardens Café, Grand Parade, BA2 4DF (07974 394154, www.paradegardens.co.uk)

In their words: “The Café’s seating area is out of doors, so we are entirely dependent on the weather and therefore open between Easter and September each year. Our customers can sit at the tables or may choose to carry a tray to any other sitting area or lawn within the Gardens.”

Garden Café, Holburne Museum, Great Pulteney St, BA2 4DB (01225 388569, www.holburne.org ) Great garden location, recommended.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Bath is a shoppers’ paradise with hundreds of independently owned stores. Amongst the key areas are:

Milsom St (BA1 1DG) Danish Design House, HAY, Seven Boot Lane, Prey

Green St (BA1 2JY) Exclusive since Jane Austen’s times, where at No. 13 Bath Oliver biscuits were first made and sold from.

Walcot St (BA1 5BG) Quirky, independent shops. Still referred to as the ‘artisan’s quarter’ of the city.

Farmers’ Market at Green Park Station (BA1 1JB, SW of Queen Square) www.greenparkstation.co.uk

PLACES TO VISIT

Roman Baths, Stall St, BA1 1LZ (01225 477785, www.romanbaths.co.uk)

Thermae Bath Spa, The Hetling Pump Room, Hot Bath St, BA1 1SJ (01225 331234, www.thermaebathspa.com ) Here you can bathe in the natural springs, and there is a fabulous view from the rooftop swimming pool

Jane Austen Centre, 40 Gay St, Bath BA1 2NT (01225 443000, www.janeausten.co.uk ) If you want chapter and verse of all the links, this is the place to come…

1 Royal Crescent (01225 428126, www.no1royalcrescent.org.uk ) to see how the smarter Georgians lived.

Victoria Art Gallery, Bridge St, BA2 4AT (01225 477233, www.victoriagal.org.uk ) Historical and contemporary European and British artworks including Bath artists and Gainsborough.

Holburne Museum, Great Pulteney St, BA2 4DB (01225 388569, www.holburne.org ) The impressive collections of Sir William Holburne, and on the top floor a visual history of Bath, including Gainsborough and Stubbs’ paintings.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Walk: The famous Bath Skyline Walk, the National Trust’s most downloaded walk. Passing Prior Park and Claverton Down, it’s highly recommended if you want more country than city.

Walk: The Avon Walkway and Cotswold Way, walk no. 7398 at www.walkingworld.com

Enjoy: A circular waymarked audio trail of the Kennet & Avon Canal in Bath. Superb and thoroughly recommended.

Read: ‘The Sack of Bath’ by Adam Fergusson

Read: ‘Nature in Towns and Cities’ by David Goode

Leave a Reply