Ancient cathedral city, gateway to the west

In walking around Exeter, three things immediately struck us: its elevated position, on a steep ridge above the River Exe, making it a natural defensive site; its proximity to nature, with hills on the horizon in every direction and the sea close by; and its student population, which during term time accounts for a quarter of the population.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 9.9 km (6.2 miles)

- Typical time: 2 ½ hours

- Height Change: 115 metres

- Start & Finish: Exeter St David’s (EX4 4NT)

- Terrain: all on pavements, some modest slopes

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Exe Valley, Southernhay Gardens, Cathedral Close, Northernhay Gardens, Bury Meadow, Lower Hoopern Valley, University Campus, Belvidere Meadows, Birks Bank Arboretum |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Exe, Taddiforde Brook |

| Stunning cityscape | Top of castle wall in Northernhay Gardens |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | The Customs House (1680), The Old City Wall (from Roman times), Exeter Cathedral (14th C), Guildhall (15th-16th C), Rougemont Castle (11th C), |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Southernhay (1780s), Upper Market (1830s) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Exeter St David’s Railway Station (1840), St David’s Church (1900), Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery (1865), Reed Hall (1850s) |

| Industrial Heritage | Exeter Quay, Iron Bridge (1834) |

| Modern (post-1918) | Cricklepit Footbridge (1988), Exeter Central Station (1930s); many building at the University of Exeter |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Tea on the Green, Chococo, The Exploding Bakery, Quayside Coffee Shop |

| Quirky Shopping | Gandy St, Fore St |

| Places to visit | Exeter Cathedral, Exeter Guildhall, Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery |

| Popular annual festivals & events | South West Food and Drink Festival, Northernhay Gardens (April), Lammas Fair and Cathedral Green Craft Fayre (July), City of Exeter Regatta (July, Exeter Quay), Northernhay Gardens Big Screen in the Park (Aug) |

City population: 129,800 (2016)

Ranking: 66th largest city in the UK

Origins: founded around AD 50 by the Romans

‘Type’ of city: an ancient cathedral city

City status: since time immemorial

Some famous inhabitants: WG Hoskins (History of the English Landscape), Tommy Cooper (comedian), Chris Martin (lead singer of Coldplay, educated at the Exeter Cathedral School), Charles Babbage (1791–1871), father of the computer

Notable city architects/planners: Thomas Sharp, town planner (1901-1978), Vincent Harris, university masterplan (1876-1971)

Number of listed buildings: 989, of which 85 are Grade I and 84 Grade II*.

Films/TV series shot here: The Onedin Line (1970s, The Quay); Broadchurch Series Two (2014, The University)

CONTEXT

Exeter is one of those cities where you are always aware of the countryside around. From any good vantage point, you can see hills in every direction; and the city doesn’t seem to have sprawled in the way that many have, giving it the character of a large town rather than a city. And within the city, there are lots of green spaces too, with the university proudly boasting that they have the highest tree per student ratio of any university in the country.

Exeter is an ancient city, first founded around AD 50 by the Romans who were attracted by the easily defensible higher ground of the ridge combined with direct access to the sea; and it has remained economically and politically active ever since, with the cathedral dating back to the 12th century. The topography of the city is dictated by its position alongside the Exe, and its shape was little altered during the 19th century as, without a source of nearby coal, it was not able to develop a significant manufacturing base.

A big change to the built environment occurred, however, as a result of Exeter being bombed by the German Luftwaffe in the Second World War, when in 1942 a large area of the city centre was flattened. The raids became known as the “Baedeker raids”, derived from a comment by Baron Gustav Braun von Stumm, a spokesman for the German Foreign Office, who is reported to have said: “We shall go out and bomb every building in Britain marked with three stars in the Baedeker Guide”. In practice, this meant Bath, Canterbury, Norwich, York and, of course, Exeter – all ancient cathedral cities. Pevsner reflected: “the German bombers found Exeter primarily a medieval city; they left it primarily a Georgian and early-Victorian city”. The Blitz destroyed about half of Exeter’s historic buildings and much of the commercial centre. Large areas of Exeter’s city centre were rebuilt in the 1950s but little attempt was made to preserve its ancient heritage. Damaged buildings were generally demolished rather than restored, and even the street plan was altered in an attempt to improve traffic circulation.

Today Exeter has the feel of a large and thriving market town rather than a city, with the university a key part of its overall topography and character.

THE WALK

I came to Exeter for the first time for the same reason that I imagine many parents do – to visit the university with my elder son. Given that part of the university experience is to get a flavour of the city and its lifestyle, we decided the night before to take a tour of the city on foot. This is the walk that we did, which gives you a bit of everything – the city, the university campus, the river and quay area – making a really interesting walk.

Exeter has one of the highest percentages of students to townsfolk anywhere in the country; comprising close to 30,000 students and staff across the University of Exeter and the University of Plymouth outpost here, they account for at least a quarter of the city’s population during term time.

Exeter St David’s railway station, where we began our ramble, has clearly benefited from the growth in the number of students, with passenger numbers more than doubling since the turn of the millennium – rather putting paid to the notion that we are running our railways into the ground. The station was first designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1840, with several later extensions. If level crossings are your subject, listen up. The one here is a six-track crossing, making it one of the widest in the UK; and, in a nice touch for walkers, we are let through on a different (and more frequent) flow than cars, neat.

In the autumn of 1960, following very heavy rain, the Exe overflowed and flooded large areas of Exeter. The water rose as high as two metres above ground level in places and 2,500 properties were flooded. These floods led to the construction of new flood defences for Exeter. The defences included three flood relief channels, one of which we are now walking alongside, and were complemented by the construction of two new very plain concrete bridges (that we walk under later) to replace the old Exe Bridge which had obstructed the flow of the river and made the flooding worse. Although the relief channels are clearly very necessary, they are not very aesthetically pleasing, being empty concrete basins, vital for 0.1% of the time when they are brimful of flood water, used occasionally by skateboarders, but rather an eyesore most of the time.

Walking along Blackaller Island, the high ground between the relief channel and the river, we soon reached Miller’s Crossing, built in 2002 to improve pedestrian and cycling communications. The bridge uses two large 6-metre ‘mill’ stones to anchor the cabling supporting the structure, a reminder of the many corn mills that lined the ‘leats’ (man-made watercourses) of Exeter in former times.

The Cricklepit Footbridge across the River Exe was built in 1988 to link the quayside with Haven Banks. Since the 1970s, the riverside has been opened up for tourism, with the regeneration of the quay and the development on the west of the river of Piazza Terracina at the canal basin. This little square located at the end of the Exeter Ship Canal basin at Exeter Quay is named after one of Exeter’s twin towns. The architecture is rather bland, but it’s a nice place to hang out when the weather is good. Overall, the quay still feels like work in progress rather than the finished thing; it was sad that in the process of regeneration they lost the Maritime Museum, but there’s plenty of outdoor activities on offer, including the Climbing Wall and Water Sports Centre.

Exeter Quay had been in regular use since Roman times. During the 13th and 14th centuries, rival merchants built weirs across the river near Topsham (6kms downstream) to prevent cargoes reaching Exeter. Between 1564 and 1566 John Trew built the first stretch of the Exeter Canal to enable delivery of cargo closer to the city. The increase in trade led to the construction of the Custom House in 1680. Exeter’s wealth came from the woollen cloth trade which reached its peak in the mid-18th century. Cloth produced in the area was finished around Cricklepit Mill and loaded onto ships at the Quayside to be taken all over the world. Warehouses were built in 1835 to house the cloth and imported goods such as olive oil, wine and salt cod. The arrival of the railway in 1844 was the beginning of the end for the canal trade as the railway was a more efficient way of transporting goods. Evidence of Brunel’s broad gauge railway can be found next to the turntable on the Piazza Terracina.

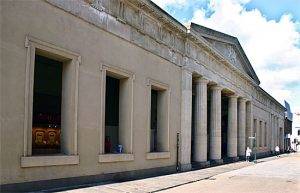

The Customs House, on the east side of the river, dates from 1680-81. It was built next to the Watergate, placing it strategically for controlling the importing of goods and assessing them before they were transported into the city. H M Customs and Excise used it until 1989. Originally, the arches at the front were open, allowing goods to be stored out of the rain. The building has three fine interior plaster ceilings produced by North Devonian, John Abbot (1639-1727). Celia Fiennes, an early 18th-century travel writer, wrote:

“…. just by this key is the Custom House, an open space below with rows of pillars which they lay in goods just as it’s unladen out of the ships in case of wet, just by are several little rooms for Land-waiters, etc., then you ascend up a handsome pair of stairs into a large room full of desks and little partitions for the writers and accountants, it was full of books and files of paper, by it are two other rooms which are used in the same way when there is a great deal of business.”

An estimated 70% of Exeter’s Old City Wall survives to this day, making it one of the most notable, if not most accessible, in the country. Originally built by the Romans, the wall was repaired in Saxon times when the defences helped repel attacks from the Vikings. The next main phase of development occurred during Norman times. Throughout the Middle Ages, the wall was important in repelling sieges and rebellions. The last time that the wall helped defend the city was during the English Civil War.

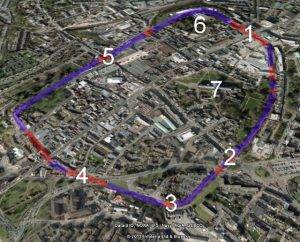

The image left shows an aerial view of the 21st-century city. The surviving portions of the city wall are highlighted in purple. Gaps in the circuit are highlighted in red. The numbers refer to the locations of the following important features: 1 The East Gate, 2 The South Gate, 3 The Water Gate, 4 The West Gate, 5 The North Gate, 6 Rougemont Castle, 7 Exeter Cathedral

The image left shows an aerial view of the 21st-century city. The surviving portions of the city wall are highlighted in purple. Gaps in the circuit are highlighted in red. The numbers refer to the locations of the following important features: 1 The East Gate, 2 The South Gate, 3 The Water Gate, 4 The West Gate, 5 The North Gate, 6 Rougemont Castle, 7 Exeter Cathedral

We came off the wall at the cut through to Cathedral Close, which was made in 1753. In 1814, Mayor Burnet-Patch found the task of clambering down the wall and back up the other side of the opening rather onerous, so he had Exeter’s first wrought-iron bridge erected, to span the gap. The footbridge retains its original lamp brackets.

At this point, we took in a quick loop of the charming, Georgian Southernhay Gardens. Even though much of it was damaged by fire in 1942 and some buildings subsequently demolished, the setting, with its mature trees surrounded by the red-brick Georgian housing, exudes an atmosphere of easy contentment.

Before the area was developed for smart housing, it had been many things, typical of a piece of land ‘edging’ the town walls: from as far back as the 13th century it was the scene of the annual Lammas Fair; the Protestant martyr Agnes Prest was burnt at the stake here in 1557; in the early 17th century the area became a pleasure gardens, until destroyed during the English Civil War; and towards the end of the 17th century it became a burial ground.

The first significant building was the establishment in Southernhay Gardens Road of the Devon and Exeter Hospital in 1741. The original, highly impressive Georgian building still survives today and is now known as Dean Clarke House, converted recently into 23 luxury apartments with a Zen garden thrown in.

The main terraces of townhouses were built from 1789. Whilst originally, they were owned by wealthy professionals, members of the gentry, retired Army colonels and the like, now they are mostly solicitors, accountants and estate agents.

Heading back under the wrought iron bridge and along Cathedral Close, the fabulous Cathedral soon came into view on our left. It was completed in about 1400 and has several notable features, including an early set of misericords, an astronomical clock and the longest uninterrupted vaulted ceiling in England. The Shell Guide has a vivid description of it: “It’s like entering the belly of a whale: pillars and roofs are grooved and vaulted like the thews and sinews of an anatomical drawing. The Beer stone is of an exquisite soft colour; grey and cream in the nave, pinker over the choir from the reflected colour of the glass.”

The Exeter Book, an original manuscript and one of the most important documents in Anglo-Saxon literature, is kept in the vaults of the cathedral. The Exeter Book dates back to the 10th century and is one of four manuscripts that between them contain virtually all the surviving poetry in Old English. It includes most of the more highly regarded shorter poems, some religious pieces, and a series of riddles, a handful of which are famously lewd. Some of the riddles are inscribed on a highly-polished steel obelisk in the High Street, a couple of hundred metres beyond Gandy St.

Very sadly, since we did the walk there has been a devastating fire in the Royal Clarence Hotel opposite the cathedral. It has since had to be knocked down. A cruel blow for a city that had already been grievously devastated by fire as a result of the wartime bombing.

Very sadly, since we did the walk there has been a devastating fire in the Royal Clarence Hotel opposite the cathedral. It has since had to be knocked down. A cruel blow for a city that had already been grievously devastated by fire as a result of the wartime bombing.

Partly because of this bombing, and partly because of insensitive development after the war (there is still a heated debate about how the blame should be apportioned), there are parts of Exeter that look sublime and there are bits that look…well, utterly mundane.

After the Exeter Blitz had destroyed 37 acres of central Exeter, the City Council were confronted with the task of planning to re-build the city. In 1944, they created the Re-planning and Reconstruction Committee after a visit by W Morrison, the Minister of Town and Country Planning. He had encouraged the council to appoint a planning consultant to advise on the rebuilding of the city. Thomas Sharp, an eminent town planner, was appointed, having already started work on a plan for Durham. His remit was to draw up an outline plan for the rebuilding of the city.

Like much development after the war, the actual results turned out to be a very mixed bag – a shortage of money and quality building materials, a pressure from traders to re-build quickly, continuing obeisance to the car, and a willingness to knock down historic buildings if they didn’t fit in with the ‘comprehensive’ redevelopment plan or threatened to be costly to restore.

Like much development after the war, the actual results turned out to be a very mixed bag – a shortage of money and quality building materials, a pressure from traders to re-build quickly, continuing obeisance to the car, and a willingness to knock down historic buildings if they didn’t fit in with the ‘comprehensive’ redevelopment plan or threatened to be costly to restore.

A walk along the High St soon demonstrates this mix of good and bad. Let’s concentrate on the good bits and ignore the bad. The Guildhall. Much of the fabric of the building is medieval, though the elaborate frontage was added in the 1590s and the interior was extensively restored in the 19th century. It has functioned as a prison, a courthouse, a police station, a place for civic functions and celebrations, a city archive store, a woollen market hall, and as the meeting place for the City Chamber and Council. If there is nothing on, you should pop in and have a quick look around.

Then we escaped from the High St (it felt like that) down Gandy St, a medieval passage that today is full of independent shops and restaurants. It is recorded that it was called Correstrete in 1265 – this name probably came from the Middle English word for ‘currying’ or the curing of leather. The street was renamed in the 17th century after Henry Gandy, Mayor of Exeter in 1661 and 1672.

Passing right through an arched passage we enter the amazing Rougemont and Northernhay Gardens (3.5 hectares, 8.6 acres). They are claimed to be the oldest public open space in England, originally laid out in 1612 as a pleasure walk for Exeter residents.

The site was quarried in Roman times for stone for the city walls. The gardens themselves incorporate a stretch of the Roman wall and the only length of Saxon town wall to be seen in England.

The early park was destroyed in the Civil War, in 1642, when large defensive ditches were dug outside the walls for the city’s defence. Soon after the Restoration, in 1664, the city set about restoring the park, planting hundreds of young elms and laying out gravel paths.

The gardens underwent a major re-landscaping in 1860, receiving its important group of monuments to major Victorian figures in the city’s history. The gardens offer views over large parts of the city and play host to several events throughout the year.

King William built Rougemont Castle. The gatehouse, which is the only part of the castle remaining, is the oldest castle building standing in Britain. It crowned a strategic position on a hill of volcanic red rock, which gave the castle’s occupants sight of all the city and beyond.

If you want a quick look at two great nineteenth-century buildings in very different styles as you come out of the park, then head left along Queen St. Shortly on your left you will see the splendidly Gothic Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery of 1865, which uses Early English and polychromatic stone to good effect. Beyond that, on the right, you will see the famous Higher Market, built in a neo-Classical style in the 1830s. Originally designed by John Dymond, it was completed by Devon-born Charles Fowler who also designed Covent Garden. But maybe don’t bother going in, as it’s just tedious chain stores.

But if you prefer your architecture of the 1930s variety, head the other way up Queen St. There is also a delightful bakery/cafe here, The Exploding Bakery.

Walking the length of Northernhay St, we followed the wall to our left, which can be seen up a little alley into Maddocks Row – here you will find a semi-circular arched opening in the wall, with a keystone dated 1772. And you can spot the wall again on the far side of a car park; and then at the end of the street, you come face to face with the very solid-looking granite wall supporting the start of the Iron Bridge.

The early 19th century saw the Improvement Commissioners directing many changes in Exeter. Boards of Improvement Commissioners were ad hoc urban local government boards created in around 300 towns and cities during the 18th and 19th centuries, each by a private Act of Parliament typically termed an Improvement Act. The powers of the boards varied but typically included street paving, cleansing, lighting, providing watchmen or dealing with various public nuisances. They were to have a fundamental influence on the development of towns and cities during the Victorian period and were the prototype for reformed municipal boroughs that eventually superseded them.

The Exeter Board was formed around 1810 to ensure a more rational approach to town planning in the city. In 1834, they commissioned the construction of the Iron Bridge over the steep-sided Longbrook Valley, immediately in front of the North Gate. The original approach road to the city, Lower North Street was narrow and difficult for horse-drawn vehicles – in fact, the valley was known as The Pit due to its steep sides and depth. Up to twenty pairs of horse-drawn carts carrying lime from the lime kilns in St Leonard’s area would pass up South Street, and down the 10-ft. wide North Street and Lower North Street, creating blockages, on their way to St David’s Down and beyond. The bridge was built parallel to, and on the left side of Lower North Street, blocking the two lower floors of the Crown and Sceptre, now the present City Gate, and houses on that side of the approach. Their second floors became the new entrances.

St David’s Church (1900) which we passed next, was designed by the architect William Douglas Caroe (we pass his main university building on the Cardiff walk) and is regarded as a very fine example of his work. Sir John Betjeman described it as “the finest example of Victorian church architecture in the south-west”.

Caroe became known as ‘a consummate master of building according to medieval precedent’, in other words, he was something of an Arts & Crafts advocate. The firm he founded, Caroe & Partners, still flourishes, specialising in ecclesiastical architecture, especially the restoration of historic churches. Caroe was also a distinguished designer of furniture, embroidery, metalwork and sculpture.

Bury Meadow (1.5 hectares, 3.7 acres), the park opposite the church, was opened to the public in 1846, on part of a site that had been used for cholera victims in the 1832 outbreak. And in the days after the Blitz, it was used for a field kitchen to feed women and children. Now, it is a pleasant green space in the city, well used and popular with students from the nearby Exeter College. It’s overlooked by the attractive paired 1860s villas of Elm Grove Road. Robert Veitch lived at No 11 from 1865-1184 and there is a blue plaque to commemorate him. He was a garden pioneer who popularised greater knowledge of plants by making different species available to people for their gardens, as well as being a landscape designer. His extensive Veitch ‘Exotic’ Nurseries covered land behind Elm Grove Road in New North Road and where Velwell Road is now. He created many new gardens including that of Streatham Hall, now part of the grounds of Exeter University, and sparked fashions in the design of rock and water gardens.

Bury Meadow (1.5 hectares, 3.7 acres), the park opposite the church, was opened to the public in 1846, on part of a site that had been used for cholera victims in the 1832 outbreak. And in the days after the Blitz, it was used for a field kitchen to feed women and children. Now, it is a pleasant green space in the city, well used and popular with students from the nearby Exeter College. It’s overlooked by the attractive paired 1860s villas of Elm Grove Road. Robert Veitch lived at No 11 from 1865-1184 and there is a blue plaque to commemorate him. He was a garden pioneer who popularised greater knowledge of plants by making different species available to people for their gardens, as well as being a landscape designer. His extensive Veitch ‘Exotic’ Nurseries covered land behind Elm Grove Road in New North Road and where Velwell Road is now. He created many new gardens including that of Streatham Hall, now part of the grounds of Exeter University, and sparked fashions in the design of rock and water gardens.

The steep Lower Hoopern Valley, with the delightfully named Taddiforde Brook running through it down to the Exe, is a natural divide between the city and the university. It really has the ‘rus in urbe’ feel about it. The site is designated as a County Wildlife Site and one of the City’s Valley Parks, of which there are five altogether.

Exeter University was founded in 1855, has expanded rapidly and is now consistently ranked in the Top 10 of universities in the National Student Survey. Streatham, which we are passing through, is the largest campus, containing many of the university’s administrative buildings, and is regarded as one of the most beautiful in the country being set in the grounds of a former Victorian mansion,  the Italianate Reed Hall.

the Italianate Reed Hall.

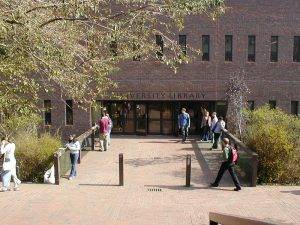

In 1928 the architect Vincent Harris was appointed to develop a master plan for the new Campus. He was responsible for many public buildings, such as the Council House in Bristol and The Central Public in Manchester, and was much influenced by contemporary American classicism. The architectural style used for the buildings at Exeter was for large neo-Georgian formal blocks built of reddish buff bricks with Lutyens-influenced stone detailing.

Although the plan was never fully realised, he was responsible for several landmark buildings on the campus, including the Washington Singer Laboratories (1931), Roborough (originally the University College’s Library), Hatherly (designed in the 1930s but not built until the 1950s), the Mary Harris Memorial Chapel (1956) and Mardon Hall (1933), the first student residence built on the campus.

Singer Laboratories

Mary Harris Memorial Chapel

The New Library

Sir Basil Spence, of Coventry Cathedral fame, was the architect of the modernist 1960s Physics Building; and more recent buildings of note include the New Library (1983), the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies and Xfi, both from the 2000s. If you are interested and want to find out more about the University of Exeter’s architectural history, take a look at the Streatham Campus Master Plan Framework .

The buildings all benefit from a fabulous setting, on a hillside with grandstand views over Exeter; and a mature tree stock of around 10,000 trees, including two arboretums, a cherry orchard and a wild conifer collection. This legacy dates back to the late 19th-century when the first specimen trees were planted in the grounds of Streatham Hall (now Reed Hall) by Richard Thornton-West. He commissioned the Veitch family of nurserymen (we passed by Robert Veitch’s home) to supply and plant trees collected from throughout the world and cultivated at their Exeter and London nurseries.

Even better, the campus grounds also have a fine collection of sculptures on display by distinguished artists such as Barbara Hepworth, Paul Mount and Geoffrey Clark; some are in University buildings and others in the grounds. You can download an excellent Sculpture Walk Leaflet showing their locations.

Having spent a lot of time wandering around the university campus, we finally made it up onto the ridge behind, the highest part of our walk at 120 metres, and started walking west along Belvidere Rd. To our right, there are fabulous views across the Duryard Valley, towards Dartmoor. Most of the land is in private ownership but there is access to Belvidere Meadows Local Nature Reserve (8 hectares, 19.8 acres) through a kissing gate.

Birks Bank Arboretum, which we passed on our way out of the campus, contains several pines which are rarely seen in the UK, including the Bristlecone Pine and the Big Cone Pine. The cones can measure up to 30cm and can weigh around 2kg when fresh.

And then we wound our way back to the station to complete a very satisfying walk.

THE ROUTE

- Head left out of station road, then left down Station Rd, cross the railway line at the level crossing and cross the River Exe

- Take the left here (between the river and the relief channel) and follow this raised path S along Blackaller Island to Miller’s Crossing

- Cross right here over the relief channel to end up on the W bank of the river

- Head S along the riverbank all the way until you reach the Cricklepit Footbridge at the quayside

- Cross over, head up Quay Hill past the Customs House and follow the path up alongside the old city wall in a NE direction, crossing Western Way, then South St, heading NE along the footpath with the wall on your immediate left, until you reach Cathedral Close

- Take a circuit here around Southernhay Gardens, before heading under the wrought iron bridge up Cathedral Close

- Go past the cathedral and then take a passage by the west end entrance, which comes out on the High St; turn right, then take the first left after Queen St, up Gandy St

- At a passage between two shops, signed ‘New Buildings’, turn right through the passageway; coming out the other side you will see an entrance in front of you to Northernhay Park, which you should take

- Once in the park, turn left and then swing round to the right and climb up to the highest point in the castle; descend on the other side and come out in the flat part of the park

- Turn left (SW), aiming for the exit in Queen St; cross over and walk down Northernhay St

- At the end turn right and head N along the route below the bridge along Lower North St, joining up with David’s Hill

- Take a right turn, just after Little Silver Lane, through St David’s Church

- Cross New North Rd and enter Bury Meadow Park, which you traverse to the other side (NE)

- Proceed E up Howell Rd, then almost immediately take the first left into Velwell Rd

- At the end of this road, a tarmacked path takes you NE along the edge of the Lower Hoopern Valley to Prince of Wales Rd

- Head NW up Prince of Wales Drive, enter the university and head right along to the end of Rennes Drive

- Head into the park, then take the first left, up alongside a small pond, then right over a small wooden bridge and exit the park at the top NE end

- Follow Higher Hoopern Lane for a short while, then when it swings round go straight ahead up a track with the university on the left, until you reach Belvidere Rd

- Turn left into Belvidere Rd and follow it down to Grafton Rd; then take a left into Grafton Rd, and the next fork right down a footpath that brings you out on Clydesdale Avenue

- Turn left here into Clydesdale Avenue, and follow it S until it meets Streatham Drive, which you follow south; swing right and cross the main New North Rd

- The path continues on the other side, down an unnamed road paved with bricks, past some student accommodation called Northfield; it then becomes a path, which swings down into Taddiford Rd and then Cowley Bridge Rd, which you cross; then take Isambard parade back to the start of your journey.

PIT STOPS

Tea on the Green, 2 Cathedral Cl, Exeter EX1 1EZ (01392 276913, www.teaonthegreen.com) Traditional ambience, stellar location

Chococo, 22 Gandy St, Exeter, EX4 3LS (01392 777338) especially good for chocolate lovers

The Exploding Bakery, Exeter Central station, Queen Street, EX4 3SB (01392 427900, explodingbakery.com). As their website explains: “The Exploding Bakery is the bastard love child of Tom Oxford & Oliver Coysh. Their sordid affair, with food, began way back at school, where they became romantically involved in Devon’s gastronomic larder.”

Quayside Coffee Shop, 85 Waterside, EX2 8GY (07975 511514)

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Gandy St, EX4 3LS More of a passage than a street; a good mix of shops and eating places

Fore St, Old West Quarter, EX4 3AN

PLACES TO VISIT

Exeter Cathedral, 1 The Cloisters, EX1 1HS (www.exeter-cathedral.org.uk )

Exeter Guildhall, 40 High St, EX4 3HP (01392 201910, https://exeter.gov.uk)

Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery, Queen St, EX4 3RX (01392 265858, www.rammuseum.org.uk

MORE TO DISCOVER

Walk: the Exeter Green Circle Walk, a 12-mile circuit that circumnavigates the city, as well as passing through the middle of it at one stage. More countryside than city, for those of you that fancy a less urban ramble.

Buy: The Exeter Street Plan, 1;10,000, shows all of the Green Circle walk, very detailed.

Follow: the Exeter City Wall Trail Approx. 2 miles Great for history buffs

Leave a Reply