Seats of Power – and several ‘lost’ rivers

This walk takes us past London’s major seats of power – the city, the church, the government and the monarchy, with the river as the umbilical cord linking them all together.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 9.6kms (6 miles)

- Typical time: 2 ½ hours

- Height change: 19ms

- Map: Google

- Start: Tower of London (EC3N 4AB)

- End of this stage: Lancaster Gate Tube Station (W2 2UE)

- Terrain: Straightforward; sturdy footwear recommended

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Mary-le-Bow Churchyard, Bernie Spain Gardens, Parliament Square, St James’ Park, Green Park, Hyde Park, Kensington Gardens, the Italian Gardens |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Thames, River Walbrook (underground), River fleet (underground), River Tyburn (underground), The Serpentine, The Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain (2004), River Westbourne (underground) |

| ‘Seafront’ | South Bank shore & beach |

| Stunning cityscape | Monument, Sky Garden, Poultry 1 Roof Garden, New Change Place, Tate Modern |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | Many Wren churches (1670s-1710s), The Monument (1671-77), Temple of Mithras (3rd century AD), St Paul’s Cathedral (1675-1711), Westminster Abbey (11th C) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | The Custom House (1813), Bank of England (from the 1730s), Mansion House (1739-52), Buckingham Palace (1820s onwards), Aspley House (1771) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Old Billingsgate (1873), Leadenhall Market (1881), Houses of Parliament (1840-60), Norman Shaw Buildings (1887-1906), The Foreign & Commonwealth Office (1868) |

| Military Heritage | The Cabinet War Rooms (1939) |

| Modern (post-1918) | The Pedway (mid 1960s), 20 Fenchurch St (The ‘Walkie Talkie’, 2014), No 1 Poultry (1997), St Paul’s Cathedral School (1960s), Millennium Bridge (2000), modern Globe (1997), Tate Modern (1947 & 2000), National Theatre (1976), Royal Festival Hall (1951), Portcullis House (2001), Serpentine Bar & Kitchen (1964) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Sky Garden Café, The CoffeeWorks Project, Tate Modern Café, The Serpentine Bar & Kitchen, The Italian Garden Café |

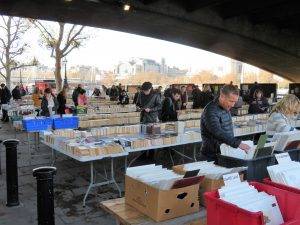

| Quirky Shopping | Leadenhall Market, Bow Lane, Gabriel’s Wharf, Southbank Centre Book Market |

| Places to visit | The Monument, Sky Garden, Temple of Mithras, Tate Modern, Cabinet War Rooms, Boating on the Serpentine |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Check out http://www.southbanklondon.com/festivals-special-events for South Bank events.

British Summer Time Hyde Park (July – music, comedy acts, film) Hyde Park Winter Wonderland (mid-Nov to Jan 2) |

City population: 8,538,689 (2011 census)

Urban population: 9,787,426 (2011 census)

Ranking: Largest city in the UK

Date of origin: 43AD

‘Type’ of city: capital city; seat of government, commerce and culture.

City status: Since time immemorial

Notable city architects/planners: Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723) – St Paul’s Cathedral, many Wren churches in the city, the Monument. Sir Horace Jones (1819-1887) – Tower Bridge, Smithfields, Leadenhall Market. The Gilbert Scotts: George (1811-1878) – Foreign & Commonwealth Office, Albert Memorial; & Giles (1880-1960) – Bankside Power Station, Waterloo Bridge, County Hall.

Number of Listed Buildings: City of London – 617, of which 85 are Grade I and 82 are Grade II* (one of the most concentrated areas of listed buildings anywhere); Southwark – 864, of which 4 are Grade I and 29 are Grade II*; Lambeth – 943, of which 6 are Grade I and 56 are Grade II*; Westminster – 3,933, of which 206 are Grade I and 364 are Grade II*

CONTEXT

The major seats of power

As we make our way from east to west, so we go through four major seats of power.

Firstly, the City of London, centre of London’s mercantile activity since Roman times and still the beating heart of our finance industry; and a medieval street pattern that despite the Great Fire has retained many of its features since medieval times.

Secondly, past two of the country’s most famous churches, St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, bastions of our religious heritage and scene of many of the coronations, weddings and famous funerals in our history.

Thirdly, on to the seats of government power, past the closed down Greater London Council building (in Mrs Thatcher’s mind at least, getting too powerful) to the Houses of Parliament and Whitehall.

And then finally, into the royal parks and the orbit of the monarchy, passing three palaces – Buckingham Palace, St James’ Palace and Kensington Palace.

Traversing the slope

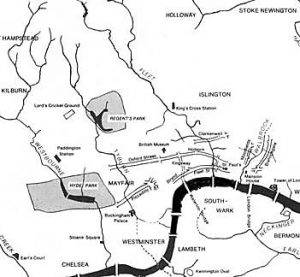

Geographically, our whole walk is traversing the slope that steadily comes down to the Thames from the north, crossing four ‘lost’ tributaries of the Thames that have their source in the heights of Hampstead (100 metres elevation) or Islington.

Our first river is the River Walbrook, passing by the Bank of England at 11 metres of elevation; next is the River Fleet, at an elevation of seven metres just to the west of St Paul’s, which Wren modified into a canal from here to the Thames; then down to sea level as we cross the Thames; then back up to Green Park and the River Tyburn at 12 metres; and finally climbing to the River Westbourne in Ladbroke grove at 19 metres. We will find evidence of all four rivers on our walk.

City planning

Finally, our walk is a living research project for students of city planning.

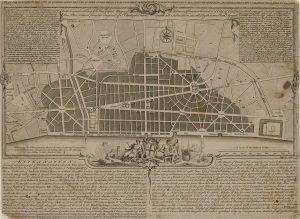

The City of London very nearly became a ‘planned city’, after the great Fire of London presented a sudden opportunity to start from scratch and design a city with wider streets and great vistas. Only one week after the final flames had gone out, Charles II issued a proclamation promising “a much more beautiful city than is at this time consumed”. He also outlined his wish to impose “order and direction”, and promised main thoroughfares like Cheapside and Cornhill would be “of such breadth as may with God’s blessing prevent the mischief that one side may suffer if the other be on fire”.

The e ver-energetic Wren had already started work on a grand plan, one containing long boulevards connecting large plazas of the kind he had seen on a visit to the French capital the previous year. He wanted to create a city of “pomp and regularity”.

ver-energetic Wren had already started work on a grand plan, one containing long boulevards connecting large plazas of the kind he had seen on a visit to the French capital the previous year. He wanted to create a city of “pomp and regularity”.

Charles II admired Wren’s design and made him one of six commissioners appointed to oversee rebuilding work. But unlike in Lisbon, where the Portuguese king ordered a completely new city after the earthquake of 1755, Charles would not get the chance to give Wren a blank canvas. Property owners soon re-asserted their rights and began building again on plots along the lines of the previous medieval street pattern.

According to the author John Schofield, a former archaeologist at the Museum of London, in the end very little changed except an (important) switch to stone rather than wood. By the time all plots were filled again in 1676, Schofield thinks “the same people were moving back in”.

The next great area of planning tussle was the Southbank, which after the war was a derelict, bombed-out area in urgent need of regeneration. The 1951 Festival of Britain transformed the area and set off a series of developments, ably assisted by a strong campaign from local residents, that has resulted today in the ‘cultural mile’ running from the new Globe to the old Greater London Council building, full of culture and entertainment and a magnet for visitors to the capital.

Finally, the ‘royal orbit’ of London, stretching from Whitehall to Kensington Palace, full of planned spaces (Horse Guards Parade, The Mall, the area around the Victoria Memorial, the balcony at Buckingham Palace providing a focal point for crowds, Constitution Hill) that allow for ceremony – in many ways very ‘un-British things’, we tend to feel more comfortable in places like the City, with its mass of unplanned streets and alleys.

You could go on this walk a dozen times and there would still be more to discover, it is so rich in history and interest.

THE WALK

Starting out from Tower Hill, we are caught up in the mêlée of tourists on their way to visit The Tower and the Crown Jewels. This third stage of our circuit takes in several of the tourist hot spots of the capital, so be prepared for crowds and selfie sticks but also, more importantly, a procession of fabulous buildings from every era.

We are almost immediately able to break free from the crowd as we head down Lower Thames St and around the front of The Customs House, dating back to 1813-17 with significant later alterations.

In 1699 an Act of Parliament was passed making the area around Billingsgate, which we walk along next, “a free and open market for all sorts of fish whatsoever”. The only exception to this was the sale of eels which was restricted to Dutch fishermen whose boats were moored in the Thames. This was because they had helped feed the people of London during the Great Fire. We’re going to be finding out a lot about the Great Fire and the devastating effect it had on the city during this first phase of our walk.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, fish and seafood were sold from stalls and sheds around the ‘hythe’ or dock here. As the amount of fish handled increased, so a purpose-built market became essential. In 1850 the first Billingsgate Market building was constructed but it proved to be inadequate and was demolished in 1873 to make way for the building which still stands today, designed by the City Architect, Sir Horace Jones. In 1982, the fish market was relocated to a new site on the Isle of Dogs. The 1875 building was then refurbished by architect Richard Rogers, originally to provide office accommodation, but its use today is as an events venue.

London Bridge was the only bridge across the River Thames until 1729. The current crossing, which opened in 1974, replaced a 19th-century stone-arched bridge, which in turn superseded a 600-year-old medieval structure. This was preceded by a succession of timber bridges, the first built by the Roman founders of London.

The Victorian bridge was famously sold to an American, Robert P. McCulloch, the founder of Lake Havasu City, a retirement real estate development on the east shore of Lake Havasu, a large reservoir on the Colorado River. He purchased the bridge as a tourist attraction for Lake Havasu, which was then far from the usual tourist track. The idea was successful, bringing interested tourists and retirement home buyers to the area. There is an urban myth that he thought he was buying Tower Bridge at the time, but probably not one that will go away.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666, Christopher Wren was instructed to design and rebuild 51 churches in the city. He was later knighted and would become the architect who, more than any other, left his mark on the city.

Nearly half of these churches still survive today, 13 in their original form, and 11 substantially altered or re-built. 8 were lost to the Blitz, 9 were demolished to make way for other buildings or street widening (mostly in the 19th century) and 10 were demolished as a result of the Union of Benefices Act (1860) that reduced the number of churches in line with the sharp decline in the City of London population in the 19th century.

We see several of Wren’s churches on our walk today, culminating of course with the greatest of them all, St Paul’s Cathedral. But first up is the St Magnus the Martyr Church. Outside the west entrance, there are stones from the original London Bridge and a wooden piece of the Roman pier. Beneath the tower is the entrance to the old London Bridge. TS Eliot wrote evocatively about this area of London in his poem The Waste Land, placing an everyday working scene cheek by jowl with a fine work of art:

“O City city, I can sometimes hear

Beside a public bar in Lower Thames Street,

The pleasant whining of a mandolin

And a clatter and a chatter from within

Where fishmen lounge at noon: where the walls

Of Magnus Martyr hold

Inexplicable splendour of Ionian white and gold”

For those of you familiar with 1960s urban planning separating walkers from traffic, we experience a classic piece of Pedway architecture next, a footbridge crossing the busy Lower Thames St. Nowhere has the urge to control walkers been stronger than in towns. It began in the 19th century with the construction of pavements designed to make walking along the street slightly safer and less grubby, and reached its zenith in the planning dictums of the 60s that aimed to separate pedestrians and traffic completely in the belief that the two would never get along.

The epitome of this philosophy was (or very nearly was) The City of London’s Pedway scheme, initiated in the mid-60s. It envisaged a 30-mile elevated walkway network around the City, from Liverpool Street to the Thames, from Fleet Street to the Tower. Parts of the network were built, notably the Barbican section, and several footbridges across major roads (one of which we are crossing now). Developers were required to provide walkways as a condition for planning consent, so there are bits and pieces in several other places. The author briefly appears in a film about it called The Pedway: Elevating London.

But the plan started to break down by the end of the 70s due to various objections, notably from conservation bodies. And in the last decade or so the policy of segregating pedestrians and traffic has gone into sharp reverse with the emerging philosophy of the ‘naked street’, where the dividing lines between pedestrian and motorist (barriers, signs, pavement edges, material changes etc.) are deliberately ‘smudged’ in the belief that this will make motorists pay much more attention.

Anyway, we get to walk along a short segment of the Pedway, and if you like concrete and chrome you will enjoy this stretch mightily.

And so, from a recent attempt at route creation, to one of the oldest. The route we are taking now is on the line of one of the most important thoroughfares in Londinium (there’s an interpretation board just after the bridge that can tell you more). It led to the Roman bridge over the Thames, which is where the church of St Magnus the Martyr stands today. The street led up to the forum and basilica, the monumental Roman administration centre, on Cornhill and Leadenhall Street.

The Monument to the Great Fire of London stands at 202ft high and exactly 202ft from where the fire started in Pudding Lane. It was designed (not surprisingly) by Sir Christopher Wren and Dr Robert Hooke and built between 1671 and 1677 on the site of St Margaret’s, the first church to burn down in the blaze. Look up and you will see a flaming gilded urn, which symbolises the fire itself. Climb the 311 steps inside for panoramic views of London.

The Monument to the Great Fire of London stands at 202ft high and exactly 202ft from where the fire started in Pudding Lane. It was designed (not surprisingly) by Sir Christopher Wren and Dr Robert Hooke and built between 1671 and 1677 on the site of St Margaret’s, the first church to burn down in the blaze. Look up and you will see a flaming gilded urn, which symbolises the fire itself. Climb the 311 steps inside for panoramic views of London.

A plaque at Faryners House immediately to the east of the Monument on Pudding Lane marks the spot where the Great Fire started at about 1 am on 2 September 1666. Experts believe Thomas Farriner forgot to properly put out the fire in the oven of his bakery, leaving sparks to set light to spare fuel and flour. Thomas Farriner avoided persecution after a Frenchman, Robert Hubert, confessed to starting the fire, even though he wasn’t in London when it began. Thomas Farriner continued to bake.

The new tower at 20 Fenchurch Street (often called the ‘Walkie Talkie’ because if its distinctive shape) was designed by Uruguayan architect Rafael Viñoly. The top-heavy design is partly intended to maximise floor space towards the top of the building, where rent is typically higher.

The Sky Garden at the top, which is our reason for visiting, was apparently key to the building getting planning permission in the first place. Despite the planning requirement being for free access, you have to book tickets online in advance or go to one of their rather expensive eateries.

It is claimed to be London’s highest public park, but since opening, there have been debates about whether it can be described as a ‘park’, and whether it is truly ‘public’ given the access restrictions. Personally, though, we loved it, yet another addition to the tourist possibilities that the capital offers. And because the building sits somewhat on its own, views are spectacular in pretty much all directions.

Leadenhall Market (weekdays 10am-6pm) is an absolute delight, dating back to the 14th century. Originally a meat, game and poultry market, it stands on what was the centre of Roman London. The ornate roof structure, painted green, maroon and cream, and cobbled floors of the current structure, designed in 1881 by Sir Horace Jones (we have already seen his hand at work on Tower Bridge and Billingsgate). Among the vendors, there are cheesemongers, butchers and florists. You are inevitably going to be tempted to stop for refreshments or a snack here. Succumb.

And now we take the advice of none other than Dr Johnson, who in 1763 told his biographer Boswell that “if you wish to have a just notion of the magnitude of this city, you must not be satisfied with seeing its great streets and squares, but must survey its innumerable little lanes and courts.” For the next quarter of an hour or so, we found ourselves happily in that state of nearly being lost but never quite, exploring myriad alleys, courtyards and passages between here and the Bank of England.

Bell Inn Yard forms one of the passageways in an intricate maze of alleys in the triangle bounded by Cornhill, Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street. The Bell Inn, which stood at the end of this Yard, dated back to the early 14th century, but was consumed by the Great Fire and never rebuilt.

George Yard was once a graceful little corner housing a variety of attractive buildings, but now it is dominated by high banking premises facing onto Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street. From the 16th century, a wine merchant’s shop stood on the corner of the Yard with a tethered live vulture as its trade sign.

The church of St Edmund, just south of George Yard, was rebuilt by Wren in 1679 after total destruction in the Great Fire, restored in 1864 and 1880, then again in 1917 after First World War damage. Its noteworthy steeple, with carvings, stone urns and projecting clock, was added in 1708. The interior, too, is an exhibition of intricately carved 17th-century woodwork; and the sanctuary screen, pulpit and font are particularly exquisite.

Bengall Court still retains the appearance and character of a 17th-century alley and there is almost a chance that here you could justifiably expect to come face to face with Dr Johnson or Charles Dickens. Along the north side of the court, there are some tiny 18th-century houses and the rear wall of the George and Vulture Tavern which has its entrance in Castle Court.

Bengall Court still retains the appearance and character of a 17th-century alley and there is almost a chance that here you could justifiably expect to come face to face with Dr Johnson or Charles Dickens. Along the north side of the court, there are some tiny 18th-century houses and the rear wall of the George and Vulture Tavern which has its entrance in Castle Court.

The Tavern boasts a history dating back to the 12th century. Chaucer is said to have frequented the place and Dick Whittington used to call in when he got bored with council meetings. Dickens referred to it in the ‘Pickwick Papers’ when Mr Pickwick and Sam Weller dined there. It is now the headquarters of the City Pickwick Club.

Originally, the tavern was merely named the George but when the Great Fire swept through these alleys it devoured everything in its path and left the George as a shell of charred embers. The ‘fire refugee’ wine merchant from George Yard, with his vulture, negotiated with the landlord for part-use of the George, and at some stage was given equal bill-ing (boo boom) in the name.

The origins of the Stock Exchange can be traced back to the coffee houses of Change Alley (previously Exchange Alley) that we explore next. The coffee house formed the 17th-century hub of daily life (and there you go thinking they didn’t really exist until Costa was invented); they were where the news was gathered and distributed; and the main places for the exchange of gossip. Here a business man could meet his client and discuss a deal in relative comfort and warmth over a coffee. By the 18th century, it was estimated that there were over 3,000 coffee houses in London.

Almost from the very outset of the new craze, Change Alley was on the map of regularly frequented byways, with the establishment of Robin’s Coffee House attracting the ‘quality’ business fraternity. Very soon after, Garraway’s and Jonathon’s coffee houses opened in the Alley.

Jonathon made his fortune by offering a welcome to the dealers who bought and sold stock when they were snubbed by the Royal Exchange in 1698. From this cosy beginning – a meeting of buyers and sellers huddled around a roaring fire – the Stock Exchange was born. It was in Jonathon’s coffee house that the notorious scheme known as the South Sea Bubble was thought up.

Popping out onto Cornhill finally, we felt very much like rabbits must do popping out of their hole into bright daylight. We were a little dazzled. Across the way stands the former Royal Exchange, founded in the 16th century by the merchant Thomas Gresham to act as a centre of commerce for the City. The present building was designed by William Tite in the 1840s. The site was notably occupied by Lloyd’s insurance market for nearly 150 years.

The Bank of England, on our right, was established in 1694 to act as the English Government’s banker. It moved here in 1734, and thereafter slowly acquired neighbouring land to create the buildings seen today. Sir Herbert Baker’s rebuilding of the Bank in the 1930s, demolishing most of Sir John Soane’s earlier building, was described by Pevsner as “the greatest architectural crime, in the City of London, of the twentieth century”. As a scant consolation, Sir John’s outer windowless wall, which is what you first see, still remains in place.

Mansion House, next up on our left, is home to the Lord Mayor of the City of London. The Lord Mayor in 1666, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, became a scapegoat for the Great Fire because of his indecisive nature. A common firefighting method at the time involved pulling down buildings to stop the fire from spreading. The Lord Mayor was woken in the early hours of the first day to grant permission to do this, but after assessing the situation decided it was not worth it. According to Samuel Pepys’ record of the events, he said that “a woman might piss it out”. Later the King ordered the demolition of houses, which could only be achieved with gunpowder because the fire was advancing faster than the houses could be demolished. The Mansion House was built between 1739 and 1752, in the then fashionable Palladian style, by the surveyor and architect George Dance the Elder.

Then 1 Poultry (1997), designed by James Stirling – that rare thing for me, a piece of post-modern architecture that I like! It stands out so much from the surrounding buildings because of it polychromatic colour effect (echoes of St Pancras), and yet it fits in well all the same. Its exterior is clad in stripes of pink and yellow limestone, and its two long facades are characterised by the layering of angular and curved forms.

Like many notable postmodern buildings, the imagery is rich in references. For example, from the sharp apex of the site, a keyhole shaped opening leads to a little-seen Scala Regia with a ramped floor; and an ancient Egyptian tomb-like opening takes visitors into the heart of the building. The roof garden definitely merits a visit too.

Like many notable postmodern buildings, the imagery is rich in references. For example, from the sharp apex of the site, a keyhole shaped opening leads to a little-seen Scala Regia with a ramped floor; and an ancient Egyptian tomb-like opening takes visitors into the heart of the building. The roof garden definitely merits a visit too.

The Prince of Wales derisively compared it to a ‘1930s wireless’, but nevertheless, it has become for the moment the most modern listed building in Britain, being listed 2*. Catherine Croft, the Director of the Twentieth Century society, is unequivocal about its merit: “It’s the most important piece of postmodern design in the UK.”

The River Walbrook, one of London’s lost rivers, runs beneath No. 1 Poultry. Although progressively culverted from the 14thcentury onwards, in the 18th century it was still described as ‘a great and rapid stream’ at this point, only 16 feet or so beneath the surface. The brook played an important role in the Roman settlement of Londinium, bringing a supply of fresh water to the walled city whilst carrying waste away to the River Thames.

The Romans built the Temple of Mithras on the east bank of the Walbrook in the middle of the 3rd century AD. It was discovered accidentally during construction work during the 1950s and will be on display again when the re-development in which it is housed, the new Bloomberg headquarters, is due to be completed in Autumn 2017. A new public route – Bloomberg arcade, choc full of good restaurants, also cuts through this development, which will be fascinating to walk through. And a pair of fountains will pay tribute to the Walbrook flowing underneath.

Walking down Pancras Lane, we come to the site of the old St Pancras Church on our right. This was one of the churches destroyed in the Great Fire that was never rebuilt, although the graveyard continued to be used until 1853. The land was left derelict for many years but was transformed into a small garden. Today you will see a range of beautifully carved benches with their designs based on the Romanesque architecture of the original church.

Walking down Pancras Lane, we come to the site of the old St Pancras Church on our right. This was one of the churches destroyed in the Great Fire that was never rebuilt, although the graveyard continued to be used until 1853. The land was left derelict for many years but was transformed into a small garden. Today you will see a range of beautifully carved benches with their designs based on the Romanesque architecture of the original church.

Well Court owes its name to the seven watering holes sunk here in Roman times. Many Roman relics have been found here during various excavation works.

Then we head along Cheapside, to Mary-le-Bow. Why that name? Well, apparently because the marshy ground on which it was built necessitated a series of brick arches beneath to support the weight – the ‘bow’ reflecting the curvature of these brick supports.

The church was rebuilt by Wren after being destroyed in the Great Fire. According to tradition, a true Cockney must be born within earshot of the sound of Bow Bells. The sound of the bells is credited with having persuaded Dick Whittington to turn back from Highgate and remain in London to become Lord Mayor.

Mary-le-Bow Churchyard was re-landscaped in 2009 and is now mostly paved, with a mature plane tree and a statue of Captain John Smith, a member of the Cordwainers’ Company (we are in the cordwainers, or shoemakers’ ward here), who founded the colony of Virginia. A plaque on the exterior of the church also records that John Milton was born near here. Does this space need a re-think, it doesn’t quite work…

On the corner of Bow Lane and Watling Street, is one of London’s oldest pubs, Ye Old Watling. Rebuilt after the Great Fire by (yes, you’ve guessed it) Sir Christopher Wren, using old ships’ timbers, the upstairs rooms were used as a drawing office during the building of St Paul’s Cathedral, whilst downstairs provided refreshment for Wren’s workmen during the lengthy construction of the cathedral (40 years in all). And these days, the Trip Advisor fraternity rate this place.

Today’s Watling Street runs along the line of the ancient Watling St, which was first used by ancient Britons and then adopted and upgraded by the Romans, connecting Canterbury with the City, crossing the Thames over the Roman London Bridge, then heading up to St Alban’s and eventually Chester and the Welsh Borders. There is a very undistinguished shopping centre on the right here, called New Change Place. It has one great virtue, though: ride up the glass elevator to the top and enjoy one of the best views of St Paul’s for free.

St Paul’s Cathedral School is a notable structure from the 1960s, echoing several of the architectural motifs of its famous neighbour yet making an individual and modern statement of its own. What an invidious architectural commission to receive, masterfully handled!

Wren’s most celebrated work, of course, is St Paul’s Cathedral, designed in the English Baroque style and built in the late 17th century after the destruction of the previous cathedral by the Great Fire. Its dome dominated the skyline for 300 years, the tallest structure in London until well into the twentieth century.

It occupies a significant place in the national identity. Services held at St Paul’s have included: the funerals of Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Sir Winston Churchill and Margaret Thatcher; jubilee celebrations for Queen Victoria; peace services marking the end of the First and Second World Wars; the wedding of Charles & Diana, the launch of the Festival of Britain (more on that later) and the thanksgiving services for the Silver, Golden and Diamond Jubilees of Elizabeth II. The image of the dome surrounded by the smoke and fire of the Blitz is one of the most iconic images of the Second World War.

The neo-Classical style of St Paul’s is more typically associated with the continent, whilst the Gothic style (which we will see in Westminster Abbey) is more closely associated with the English tradition. Opinions of Wren’s cathedral differed when it was first built, with some loving it: “Without, within, below, above, the eye / Is filled with unrestrained delight”; while others hated it: “…There was an air of Popery about the gilded capitals, the heavy arches…They were unfamiliar, un-English…”. No-one, however, seems to doubt the wonderfulness of the dome; described by Sir Banister Fletcher as “probably the finest in Europe”, by Helen Gardner as “majestic”, and by Pevsner as “one of the most perfect in the world”.

Heading down the pedestrian route to the Thames from here, we soon get our first good view of the stunning Millennium Bridge, first opened in June 2000. It quickly became known as the ‘Wobbly Bridge’ after participants in a special charity event to open the bridge experienced an unexpected swaying motion. The bridge’s movements were caused by a ‘positive feedback’ phenomenon, known as ‘Synchronous Lateral Excitation’. The natural sway motion of people walking caused small sideways oscillations in the bridge, which in turn caused people on the bridge to sway in step, increasing the amplitude of the bridge oscillations and continually reinforcing the effect. A wonderful demonstration of the power of urban rambling really!

The bridge was closed for almost two years while modifications were made to eliminate the wobble entirely. The modifications involved the retro-fitting of 37 fluid viscous dampers (energy dissipating) to control horizontal movement and 52 tuned mass dampers (inertial) to control vertical movement. The bridge was reopened in 2002.

Today the Millennium Bridge most definitely works. People simply love walking across it, enjoying the juxtaposition of land and water, beauty and function perfectly combined. It is one of the most glorious bridges in the world, and it’s just for walkers! Mind you, it’s also become the epicentre of selfies and it can take a while to cross!

The cultural (s)mile

As we cross the bridge, The Shakespeare Globe is on our left and Tate Modern just to the right. The original Globe Theatre was built in 1599, destroyed by fire in 1613, rebuilt in 1614, and then demolished in 1644. Southwark (where we are now) was a good place for a theatre because it was outside the control of the city officials, who were hostile to theatres. People went to Southwark to be entertained. It already had two theatres, animal baiting arenas, taverns and brothels.

The modern Globe Theatre reconstruction that we see today is based on available evidence of the original buildings. It was created by the American actor and director Sam Wanamaker, built only a stone’s throw from the original site and opened in 1997.

The Tat e Modern used to be the Bankside Power Station. It was originally designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the designer of the famous red telephone boxes (like the one in the St Paul’s picture), Battersea Power Station and Waterloo Bridge amongst many others. It became operational in 1947 and closed in 1981. For many years after closure, the vast structure was at risk of being demolished by developers. It was saved in 1994 when the Tate Gallery announced that it would be the home for the new Tate Modern. Herzog & de Meuron were the architects, the re-opening taking place in 2000.

e Modern used to be the Bankside Power Station. It was originally designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the designer of the famous red telephone boxes (like the one in the St Paul’s picture), Battersea Power Station and Waterloo Bridge amongst many others. It became operational in 1947 and closed in 1981. For many years after closure, the vast structure was at risk of being demolished by developers. It was saved in 1994 when the Tate Gallery announced that it would be the home for the new Tate Modern. Herzog & de Meuron were the architects, the re-opening taking place in 2000.

More recently, the impressive Tate Modern extension, named the Tate Modern Switch House, has been added at the back of the site. It is made of brick in harmony with the original building and stands as a squat, truncated pyramid, twisting as it rises, punctured only by thin slit windows. I love the phrase that the Guardian used to describe it: “The bricks are draped like chainmail over a muscular concrete cage”. Cracking building, not popular I gather with the penthouse apartments next door that it overlooks.

And so, under Blackfriars Bridge, o n the north side of which our second ‘lost’ river the River Fleet meets the Thames. It is a rather unassuming arch hidden under the bridge on the other side, so rather hard to see, but here’s a picture:

n the north side of which our second ‘lost’ river the River Fleet meets the Thames. It is a rather unassuming arch hidden under the bridge on the other side, so rather hard to see, but here’s a picture:

In the 1920s The Liebig Extract of Meat Company, makers of the OXO cube, took over an old power station on the wharf just beyond the bridge as their UK base. They incorporated the design as windows on the old tower to get around a ban on skyline advertising, and to this day it remains a major landmark.

The residents of the network of streets adjacent to Coin Street, on the other side of Bernie Spain Gardens, comprised a mix of people, including families who’d lived there for generations and young professionals like Bernie Spain, who was central in mobilising this group to oppose the plans to re-develop the district commercially, as proposed in the 1970s. The Coin Street Action Group was set up and formulated proposals for an alternative scheme, which included affordable family housing, a new riverside park and walkway, managed workshops, shops, and cultural and leisure facilities.

In 1984, the pressure paid off and the developers withdrew and sold the site to the council. The Action Group obtained a loan and bought the entire 13-acre site. They formed Coin Street Community Builders and set about realising their alternative vision. From 1984 to 1988 they oversaw the demolition of derelict buildings and the completion of a new riverside walkway, opening up spectacular views across to St Paul’s and the City. In 1988, a riverside park was laid over an old cold storage site spanning both sides of the Upper Ground. In acknowledgement of her pioneering community work and love of gardening, the park was named after Bernie and was opened to the public in 1988. What an amazing achievement, that we all benefit from as we walk along the banks of the river.

Next, we walk past the spot where the garden bridge was going to be…but hang on a minute, it’s not going to be any more. What began as a dream of nature in the city became a stand-off about access and expense, and in 2017 the project was ditched, presumably for good.

The £185Mn plan – to build a pedestrian bridge across the Thames full of trees and flowers – seemed like a great idea when it was first muted but it met with stiff opposition, not least because it was, in fact, a private enterprise and the bridge would be closed a number of days per year for private events. According to a Guardian report of the time, “It’s all part of the stealth privatisation of public space. A few trees plonked on a bridge are nothing but greenwash – environmental camouflage for a corporate takeover of open space that currently belongs to us all.”

It was VERY expensive, too. By contrast, a group of enterprising locals upstream in Barnes are aiming to convert an existing disused railway bridge into a garden walkway linking the neighbourhoods of Barnes and Chiswick (see our Richmond Park walk that takes this route) – basically just plant a few seeds and away you go – like the sound of that, and MUCH cheaper!

I remember being warned by my parents that the National Theatre (1976) was a very objectionable, ‘brutalist’ building (which they said in the same way they said ‘American’) as we went to see an early production there of No Man’s Land starring those two great thespians, John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson. As a young lad, I remember the play well, but the thing that has stuck with me most is the ‘open Scandinavian-style’ sandwiches available in the foyer, which seemed so ‘modern’ at the time. It turns out that even the crockery and cutlery that we were served with were selected by Denys Lasdun, the architect, who had an eye for detail more akin to the Arts & Crafts Movement than the Brutalists. Anyway, I loved the place and the experience, especially the open carpeted foyers, quite different from the very constricted West End theatres.

Architectural opinion wasn’t just split in our family at the time of construction. Even enthusiastic advocates of the Modern Movement such as Pevsner found the Béton brut concrete both inside and out overbearing. Prince Charles was at it again with his pithy rejoinders, describing the building as “a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting”. Sir John Betjeman, however, a man not noted for his enthusiasm for the modern, was effusive in his praise and wrote to Lasdun stating that he “gasped with delight at the cube of your theatre in the pale blue sky and a glimpse of St. Paul’s to the north of it. It is a lovely work and so good from so many angles…it has that inevitable and finished look that great work does.”

I think the building is best summed up in Lasdun’s own phrase of “architecture as urban landscape.” In the dusk, it looks like a range of foothills, with many different valleys, bowls and ridges giving it interest and ‘ways in’, with lights playing on the different spaces and angles in myriad ways.

The South Bank

Now I bet you weren’t expecting a beach on this urban ramble, but depending on the time of year and time of day, I might be able to offer you two. First of all, twice a day at low tide, there’s a beach of sorts alongside the river (take care if you decide to make a further inspection), where you will often see people kicking pebbles about or even making sandcastles. Second, in the summer months (May-Sept), there’s a ‘pop-up’ beach constructed in front of the South Bank, nearly the length of a football pitch and apparently requiring 85 tonnes of sand to fill it – and topped off with beach huts, parasols and Brazilian cocktails.

Now I bet you weren’t expecting a beach on this urban ramble, but depending on the time of year and time of day, I might be able to offer you two. First of all, twice a day at low tide, there’s a beach of sorts alongside the river (take care if you decide to make a further inspection), where you will often see people kicking pebbles about or even making sandcastles. Second, in the summer months (May-Sept), there’s a ‘pop-up’ beach constructed in front of the South Bank, nearly the length of a football pitch and apparently requiring 85 tonnes of sand to fill it – and topped off with beach huts, parasols and Brazilian cocktails.

In 1951, just six years after the war had finished, Britain’s cities still showed the scars of war. With the aim of promoting the feeling of recovery, the Festival of Britain opened in the early summer of 1951, celebrating British industry, arts and science and inspiring the thought of a better Britain. Gerald Barry, the Festival Director, described it as “a tonic to the nation”. It was also the centenary of the iconic 1851 Great Exhibition, which had been such a high point for British influence and ingenuity.

The main site of the Festival was constructed here on the South Bank, which had been left untouched since being bombed in the war. In keeping with the principles of the Festival, a young architect aged only 38, Hugh Casson, was appointed Director of Architecture; and he appointed other young architects to design its buildings. With Casson at the helm, it proved to be a perfect time to showcase the principles of urban design that would feature in the post-war rebuilding of London and other cities.

The main site featured the largest dome in the world at the time, standing 93 feet tall with a diameter of 365 feet (the inspiration for the Millennium Dome, aka the O2 Arena). This held exhibitions on the theme of discovery such as the New World, the Polar regions, the Sea, the Sky and Outer Space. It also included a 12-ton steam engine on show. Adjacent to the Dome was the Skylon, a breath-taking, futuristic-looking structure. The Skylon was an unusual, vertical cigar-shaped tower supported by cables that gave the impression that it was floating above the ground.

Always planned as a temporary exhibition, the Festival ran for five months over the summer. It was a huge success and turned over a profit as well as being extremely popular. In the month that followed the closure, however, a new Conservative government was elected to power. It is generally believed that the incoming Prime Minister Churchill considered the Festival a piece of socialist propaganda, and the order was quickly made to level the South Bank site, removing almost all traces of the Festival. The only feature to remain was the brilliant Royal Festival Hall which is now a Grade I listed building, the first post-war building to become so protected.

The Festival site was, over the following thirty years, developed into the South Bank Centre, the popular arts complex we see today comprising the Royal Festival Hall, the National Film Theatre, the Queen Elizabeth Hall, the Purcell Room and the National Theatre.

By the mid-19th century, Westminster Bridge was subsiding badly and expensive to maintain. The current bridge was opened in 1862, designed by Thomas Page, with Gothic detailing by Charles Barry. It is the oldest road bridge across the Thames in central London. It is apparently painted green to match the seats in the House of Commons; whilst Lambeth Bridge, the next bridge upstream, is painted red to match the colour scheme in the House of Lords.

It’s hard to know what to add about a building as iconic as the Houses of Parliament. To me, it epitomises ‘Empire Victorian’ architecture and is also a symbol of how we muddle along as a nation – no fundamental restoration has been carried out on the building since the war, when it was damaged by bombs, and the country is now faced with a repair bill of £4Bn + and MPs and Lords will need to vacate the building completely for 6 years. MPs could be housed in a “pop–up Parliament” based in Horse Guards Parade, designed by Norman Foster and envisaged as a ‘showcase of British design’.

Sir Charles Barry’s collaborative design for the Palace of Westminster used the Perpendicular Gothic style, which was popular during the 15th century and returned during the Gothic revival of the 19th century. Barry was a classical architect, but he was aided by the Gothic architect Augustus Pugin, who designed much of the interior and was an influence throughout.

Opposite the Houses of Parliament by the river is Portcullis House, with its vast glass atrium, opened in 2001. The building’s curious profile, with its rows of tall chimneys, is intended to recall the Victorian Gothic design of the Palace of Westminster and to fit in with the chimneys of the buildings next door. These delightful buildings were built by renowned architect Richard Norman Shaw between 1887 and 1906, and were originally the location of New Scotland Yard; but from 1979, they have been used as Parliamentary offices.

Opposite the Houses of Parliament by the river is Portcullis House, with its vast glass atrium, opened in 2001. The building’s curious profile, with its rows of tall chimneys, is intended to recall the Victorian Gothic design of the Palace of Westminster and to fit in with the chimneys of the buildings next door. These delightful buildings were built by renowned architect Richard Norman Shaw between 1887 and 1906, and were originally the location of New Scotland Yard; but from 1979, they have been used as Parliamentary offices.

There have been traffic bottlenecks in Parliament Square almost since time began, certainly since long before the motor car. It was laid out in 1868 in order to open up the space around the Palace of Westminster and improve traffic flow. At this point, it also featured the world’s first road traffic signal, which looked like any railway signal of the time, with waving semaphore arms and red-green lamps, operated by gas, for night use. Unfortunately, it exploded, killing a policeman. The accident discouraged further development until the era of the internal combustion engine. Modern traffic lights are in fact an American invention. Red-green systems were installed in Cleveland in 1914; and the first lights of this type to appear in Britain were in London, on the junction between St James’s Street and Piccadilly, in 1925.

The four sides of Parliament Square reflect the different powers of the country: legislature to the east (the Houses of Parliament), executive offices to the north (Whitehall), the judiciary to the west (the Supreme Court), and the church to the south (Westminster Abbey). With the fifth influence – the leaders and the populace in the square itself – both those who have shaped history in the eleven statues, including Churchill’s; and the ‘vox populi’ in the shape of campaigners and demonstrators. This is the stage of British life and history.

The four sides of Parliament Square reflect the different powers of the country: legislature to the east (the Houses of Parliament), executive offices to the north (Whitehall), the judiciary to the west (the Supreme Court), and the church to the south (Westminster Abbey). With the fifth influence – the leaders and the populace in the square itself – both those who have shaped history in the eleven statues, including Churchill’s; and the ‘vox populi’ in the shape of campaigners and demonstrators. This is the stage of British life and history.

Westminster Abbey is more in the Gothic style you’d expect of an English church, dating back to the 11th century. Since 1066, when Harold Godwinson and William the Conqueror were crowned, the coronations of all British monarchs have taken place here.

Poet’s Corner Poets’ Corner is in a section of the South Transept. Many poets, playwrights, and writers are buried or commemorated here, including a monument to William Wordsworth, who of course famously wrote ‘Upon Westminster Bridge’ in 1807:

Earth has not anything to show more fair:

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendour, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

So, the poet who perhaps did more than anyone to ‘invent’ the pastoral idyll in contrast to the turmoil and ugliness of city life had a moment of ‘urban enlightenment’ too! The same metaphorical journey I made a few years ago when I started to research and write Urban Rambles.

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office occupies a building on the right of King Charles St, which we walked down next. It originally provided premises for four separate government departments: the Foreign Office, the India Office, the Colonial Office and the Home Office. It was designed by George Gilbert Scott and completed in 1868 in the Italianate style; Scott had initially envisaged a Gothic design, but Lord Palmerston, the then Prime Minister, insisted on a classical style.

George Gilbert Scott was the most prolific architect of his age. His works spanned the empire, from New Zealand to Newfoundland. In England alone, he designed 800 buildings and oversaw hundreds more restorations. He produced churches, schools, hospitals, workhouses, asylums and vicarages galore. He has 607 structures listed as historic, more than any other architect (next is Lutyens, with 402), including the Albert Memorial (you might consider a short detour to see this later in the walk), the Foreign Office, Edinburgh Cathedral and the universities of Glasgow and Bombay. Furthermore, Scott restored 18 of the 26 English medieval cathedrals.

The Cabinet War Rooms are at the end of the street on the left down the Clive steps. During their operational life, two of the Cabinet War Rooms were of particular importance. The Map Room was in constant use and manned around the clock by officers of the Royal Navy, British Army and Royal Air Force. These officers were responsible for producing a daily intelligence summary for the King, Prime Minister and the military Chiefs of Staff.

The other key room was the Cabinet Room. Following Winston Churchill’s appointment as Prime Minister, Churchill visited the Cabinet Room in May 1940 and declared: “This is the room from which I will direct the war”. In total 115 Cabinet meetings were held at the Cabinet War Rooms.

Yippee, we’ve made it into St James’ Park (23 hectares, 57 acres). Walk the elegant paths of St James’s Park today and it is difficult to imagine that pigs once grazed here. But, 470 years ago, the St James’s area was known mainly for farms, woods and a hospital for women lepers. It was a swampy wasteland that was often flooded by the River Tyburn on its way to the Thames. It was, however, ideal land for deer hunting, the passion of royalty at the time. The royal court was based at the Palace of Westminster and in 1536, King Henry VIII decided to create a deer park conveniently nearby. He acquired land in St James’s, put a fence around it and built a hunting lodge that later became St James’s Palace.

The deer park stayed largely the same until 1603 when James I became king. He drained and landscaped the park. At the west end, near what is now Buckingham Palace, there was a large pool known as Rosamond’s Pond. At the east end, there were several small ponds, channels and islands. These were used as a duck decoy to lure birds that were shot for the royal table.

King James kept a collection of animals in the park, including camels, crocodiles and an  elephant. There were also aviaries of exotic birds along what is now Birdcage Walk. The park became more formal when Charles II became king in 1660. He had been in exile in France after the English Civil War and had been impressed by the elaborate gardens belonging to the French royal family. When Charles returned home, he ordered the redesign of St James’s Park.

elephant. There were also aviaries of exotic birds along what is now Birdcage Walk. The park became more formal when Charles II became king in 1660. He had been in exile in France after the English Civil War and had been impressed by the elaborate gardens belonging to the French royal family. When Charles returned home, he ordered the redesign of St James’s Park.

The new park was probably created by the French landscaper, Andre Mollet. The centrepiece was a straight canal, 2,560ft long and 125ft wide, lined on each side with avenues of trees. The new park was opened to the public for the first time. A tradition also began at this time that continues today. In 1664, a Russian ambassador presented a pair of pelicans to the king. Pelicans are still offered to the park by foreign ambassadors.

In the 1820s, the park received another major makeover. It was remodelled in the new naturalistic style. The canal became a curving lake. Winding paths replaced formal avenues. Fashionable shrubberies took over from traditional flower beds. The work was commissioned by the Prince Regent, later George IV. It was part of a huge project that created many of London’s best-known landmarks, including Regent’s Park (which we pass through on Stage 4) and Regent’s Street. It was overseen by the architect and landscaper, John Nash. He produced the designs in 1827 and within a year the work on St James’s Park was finished.

The Mall began as a field for playing pall-mall (an early version of croquet). In the 17th and 18th centuries, it was a fashionable promenade, bordered by trees. It was not until the 20th century that it was envisioned as a ceremonial route, matching the creation of similar ceremonial routes in other European cities. As part of the development – designed by Aston Webb – a new façade was constructed for Buckingham Palace, and the Victoria Memorial was erected. The length of The Mall from where it joins Constitution Hill at the Victoria Memorial end to Admiralty Arch is exactly 0.5 nautical miles; and continuing the nautical theme, each lamp post along the mall has a ship on the top of it, each one representing one of the ships that took part in the battle of Trafalgar. And to add to the sense of ceremony, since the 1950s the surface of The Mall has been coloured red to give the effect of a giant red carpet leading up to Buckingham Palace.

Buckingham House remained the property of the Dukes of Buckingham until 1761 when George III acquired the whole site as a private family residence for his wife, Queen Charlotte, and their children. It was remodelled with ceilings designed by Robert Adam and painted by Giovanni Battista Cipriani.

In the 1820s, towards the end of George IV’s reign, John Nash enlarged Buckingham House into the imposing U-shaped building that was to become Buckingham Palace. Much enlargement and extension took place throughout the 19th century, including the addition of the famous balcony. From here Queen Victoria saw her troops depart to the Crimean War and welcomed them on their return.

Green Park (19 hectares, 47 acres) is said to have originally been a swampy burial ground for lepers from the nearby hospital at St James’s. It was first enclosed in 16th-century when it formed part of the estate of the Poulteney family. In 1668, an area of the Poulteney estate known as Sandpit Field was surrendered to Charles II, who made the bulk of the land into a Royal Park known as Upper St James’s Park and enclosed it with a brick wall. He laid out the park’s main walks and built an ice house there to supply him with ice for cooling drinks in summer.

In 1820, John Nash landscaped the park, as an adjunct to St. James’s Park. It remains a personal favourite of mine, despite its simplicity, consisting almost entirely of mature trees and no flower beds. I used to work in an office on the north side of Piccadilly, and we would pop out here for a sandwich lunch or to play a game of rounders after work.

The Royal Air Force Bomber Command Memorial is in the north-east corner of the park, commemorating the crews of RAF Bomber Command who embarked on missions during the Second World War to mark the sacrifice of 55,573 aircrew. Liam O’Connor designed the memorial, built of Portland stone, which features a bronze 9-foot (2.7 m) sculpture of seven aircrew returning from a bombing mission, designed by the sculptor Philip Jackson.

The Wellington Arch is in the centre of Hyde Park Corner which, like Parliament Square, was a traffic pinch-point, significantly improved when the underpass was built in 1962 as part of the Park Lane Improvement Scheme that also saw Park Lane duelled for most of its length, but also sadly the hideous Park Lane Hotel sneaked its way in at this point. Aspley House, stranded in the middle now, was the home of the first Duke of Wellington.

Hyde Park (142 hectares, 350 acres) is London’s most splendid space, although some criticise it for being too flat. I loved one gentleman’s suggestion in a letter to the Times recently that all the earth excavated by the plutocrats’ hollowing out massive basements in Knightsbridge should be dumped in Hyde Park and fashioned into hillocks, as happened to such good effect in Central Park in New York. Hyde Park was originally created for hunting by Henry VIII in 1536. He acquired the manor of Hyde from the canons of Westminster Abbey, who had held it since before the Norman Conquest; it was enclosed as a deer park and remained a private hunting ground until James I permitted limited access to gentlefolk, appointing a ranger to take charge. Charles I created the Ring (north of the present Serpentine boathouses), and in 1637 he opened the park to the general public.

Rotten Row is a broad sand-covered track running along the south side of the park, leading from Hyde Park Corner to Serpentine Road. It was established by William III at the end of the 17th century. Having moved the court to Kensington Palace, he wanted a safer way to travel to St James’s Palace. He created the broad avenue through the park, lit with 300 oil lamps, the first artificially lit highway in Britain. The lighting was a precaution against highwaymen, who lurked in the park at the time. The track was called ‘Route du Roi’, which was eventually corrupted into ‘Rotten Row’. During the 18th and 19th centuries, it became a fashionable place for upper-class Londoners to be seen horse riding, and people still ride horses along it today (we pass the stables on Stage 4 of our walk). Designated as a public bridleway in the 1730s, Rotten Row is today one of the most famous urban riding grounds in the world.

The first significant landscaping of Hyde Park was undertaken by Charles Bridgeman in the 1730s. This included the creation of the Serpentine (inspired by its snake-line shape and a ‘must-have’ feature on country estates at the time), formed by damming the River Westbourne that flowed through the park. The Westbourne has its source in Hampstead Heath at Whitestone Pond. Its most ‘famous’ sighting today is as a steel conduit running over the Sloane Square underground station platform.

One of the most important events to take place in the park was the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Crystal Palace was constructed on the south side of the park, designed by Joseph Paxton. It was prefabricated, assembled on site and used large quantities of iron and glass – it could easily sound like a High-Tech building from today rather than the mid-19th century. Six million people- equivalent to a third of the population of Britain at the time—visited the Great Exhibition. The event made a healthy financial surplus, that was used to fund the creation of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum. But there was opposition to the building remaining after the closure of the exhibition (echoes of the 1951 Festival?), and it was moved to Sydenham Hill in South London, where it remained a major venue until 1936 until tragically gutted by fire. It’s a shame we can’t see it today. Le Corbusier wrote about it thus: “(It is) one of the great monuments of nineteenth-century architecture.…I could not tear my eyes from the spectacle of its triumphant harmony.”

One of the most important events to take place in the park was the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Crystal Palace was constructed on the south side of the park, designed by Joseph Paxton. It was prefabricated, assembled on site and used large quantities of iron and glass – it could easily sound like a High-Tech building from today rather than the mid-19th century. Six million people- equivalent to a third of the population of Britain at the time—visited the Great Exhibition. The event made a healthy financial surplus, that was used to fund the creation of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum. But there was opposition to the building remaining after the closure of the exhibition (echoes of the 1951 Festival?), and it was moved to Sydenham Hill in South London, where it remained a major venue until 1936 until tragically gutted by fire. It’s a shame we can’t see it today. Le Corbusier wrote about it thus: “(It is) one of the great monuments of nineteenth-century architecture.…I could not tear my eyes from the spectacle of its triumphant harmony.”

We are now on the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Walk, heading along the south side of the Serpentine. It is marked with ninety individual plaques, each of which has a heraldic rose etched in the centre made of aluminium. Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who was the Chairman of the Diana, Princess of Wales, Memorial Committee was quoted as saying it is “one of the most magnificent urban parkland walks in the world”. Can’t really argue with that, seven miles altogether, all within the four parks of Kensington Gardens, Hyde Park, Green Park and St James’ Park.

Make sure you don’t miss The Rose Garden. The Garden opened in 1994 and the design was developed from the concept of horns sounding one’s arrival into Hyde Park from Hyde Park Corner. The central circular area enclosed by the yew hedge is imagined to be the mouth of a trumpet or horn and the seasonal flower beds are the flaring notes coming out of the horn (the easiest way to see this is in fact on Google Earth). The best time to see the roses is early summer, although they continue to flower through to the first frosts.

The first building we come to on the lakeside is the Serpentine Bar & Kitchen with its distinctive zig-zag roof, built in 1964 by Patrick Gwynne and 2* listed. The finishes are fine, especially the floor of Brescia Violetta marble, which runs unbroken from the café to the outside terraces.

Walking along the south of the lake, we come to the gloriously named Serpentine Lido, not perhaps the lido of one’s dreams, but the very place where mad English men and women go swimming every year on Christmas Day since time immemorial (well 1864 …). The Serpentine Swimming Club is the oldest swimming club in Britain. I particularly enjoy this extract from their website:

For some extraordinary reason, the activities of the SSC still continue to excite the media, especially in the winter. Foreign journalists from as far away as Japan have also shown an interest in what appears to some to be the masochistic pleasure SSC members find in swimming in cold water. Perhaps one foreign journalist, in particular, captured the spirit of the SSC. In a long article appearing in “The American Swimmer” in its number of October 1923 Captain Colbridge of the United States Army notes a line up before the start of a race. “The elderly gentleman on your right, with the stooped shoulders, keeps a sweet shop in Maida Vale, the one next to him is a tobacconist in High Holborn. The man on your left is a major in the army. Over the way is a waiter from the Trocadero Restaurant. Down a bit, you see the physician to the Queen. Here is a haberdasher’s clerk from Marylebone Road. Such is the club you join, a democratic amalgamation of persons interested in swimming and caring not for anything but their mutual swimming interest.” His observation encapsulated the very essence of the SSC’s membership as it was and as indeed is now.

At the 2012 London Olympic Games, the Serpentine was memorably used as the venue for the swimming portion of the triathlon and for the marathon swimming events.

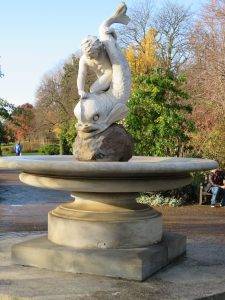

The Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain, next up on our left, was designed by Kathryn Gustafson, an American landscape artist. She said she had wanted the fountain to be accessible and to reflect Diana’s ‘inclusive’ personality. Despite the standard habit of British controversy around the launch of anything new and innovative (in this case there were some problems with people slipping when it opened in 2004), it has become a star London attraction, successful in every way. It’s beautiful to watch the water gliding and gurgling along the Cornish granite and to watch children and adults alike enraptured by it as they paddle and splash.

The Princess of Wales Memorial Fountain, next up on our left, was designed by Kathryn Gustafson, an American landscape artist. She said she had wanted the fountain to be accessible and to reflect Diana’s ‘inclusive’ personality. Despite the standard habit of British controversy around the launch of anything new and innovative (in this case there were some problems with people slipping when it opened in 2004), it has become a star London attraction, successful in every way. It’s beautiful to watch the water gliding and gurgling along the Cornish granite and to watch children and adults alike enraptured by it as they paddle and splash.

Kensington Gardens (111 hectares, 270 acres) are technically everything the other side of the Serpentine Bridge, although it feels like a continuation of the park and you will hardly notice.

The Peter Pan Statue was erected in Kensington Gardens in 1912, featuring squirrels, rabbits, mice and fairies climbing up to Peter, who is stood at the top of the bronze statue. The author, JM Barrie, lived close to Kensington Gardens and published his first Peter Pan story in 1902, using Kensington Gardens for inspiration. In his Peter Pan tale, The Little White Bird, Peter flies out of his nursery and lands beside the Long Water. The statue is located at this exact spot.

The Italian Gardens are a 150-year-old ornamental water garden located on the north side of Kensington Gardens near Lancaster Gate. It is believed to have been created as a gift from Prince Albert to Queen Victoria. They were based on gardens he had previously created at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

The Royal Lancaster Hotel was originally built in 1966 as an office block and converted to a hotel shortly after. It’s a mystery to me how they ever got planning permission, it’s completely out of proportion with the surrounding environment. The architect was Richard Seifert, best known in London for Euston Station, Centre Point and King’s Reach Tower (which we passed earlier). The list says it all. Time to escape underground.

The Royal Lancaster Hotel was originally built in 1966 as an office block and converted to a hotel shortly after. It’s a mystery to me how they ever got planning permission, it’s completely out of proportion with the surrounding environment. The architect was Richard Seifert, best known in London for Euston Station, Centre Point and King’s Reach Tower (which we passed earlier). The list says it all. Time to escape underground.

THE ROUTE

- Set out NW along Lower Thames St, with the Tower of London directly behind you; turn left down Water Lane and then follow the riverfront path, first past the Custom House and then Old Billingsgate

- Turn right to pass by St Magnus the Martyr Church and take the 1970s bridge across Lower Thames St, turning left on the other side, then right to the Monument

- Head E from here along Monument St, then first left up Pudding Lane, first right along St George’s Lane (which becomes pedestrian), then across Botolph Lane into Botolph Alley, left at the end up Lovat Lane, across Eastcheap into Philpott Lane and up to Fenchurch 20 (the Walkie Talkie)

- Continue along Philpott Lane, crossing Fenchurch St into Lime St, then bearing left at Lime St Passage to walk through Leadenhall Market

- On emerging on the W side into Gracechurch St, cross over and continue heading W via Bell Inn Yard, George Yard, Bengal Court, across Birchin Lane to Change Alley to emerge on Cornhill opposite the Royal Exchange

- Then proceed west along Poultry, past the Mansion House and No. 1 Poultry, turning left (S) just after St Mary-le-Bow into Bow Churchyard and then swinging left behind the church into Bow lane, where you head right

- Turn right at the bottom of Bow Lane along Watling St, all the way to the south-east corner of St Paul’s

- Head S when you are level with the dome, down Sermon Lane, then Peter’s Hill, across Victoria St, continuing south across the Millennium Bridge

- From here you take the river path all the way along until you reach Westminster Bridge, which you cross. Entering Parliament Square, turn right up Whitehall and then left along King Charles St to reach St James’s Park

- Head W across the park, crossing St James’ Park Lake by the bridge in the middle, then continuing across the mall to the east side of Clarence House, then W across Green Park past the Bomber Command Memorial to the end of the park; taking the crossing into the Wellington Arch, then the subway to exit into Hyde Park

- Once in Hyde Park, head to the NE end of the Serpentine by way of the delightful Rose Garden; then track the southern shore of the lake, crossing the Ring and continuing on the other side until you reach the statue of Peter Pan; then, walking alongside the Italian Gardens, crossing the Bayswater Rd to Lancaster Gate tube. End of stage 3.

PIT STOPS

Sky Garden Café (but you need to book online in advance), 1 Sky Garden Walk, EC3M 8AF (020 7337 2344, https://skygarden.london)

The CoffeeWorks Project, 4 Whittington Ave, EC3V 1PP (north exit from Leadenhall Market) (020 7621 0040, www.coffeeworksproject.com/visit-leadenhall-coffee-shop

Tate Modern Café, Level 1, Bankside, SE1 9TG (www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern/cafe ).)Also, The Espresso Bar on level 3 for still better views.

The Serpentine Bar & Kitchen, Serpentine Road, Hyde Park, W2 2UH (020 7706 8114, www.serpentinebarandkitchen.com)

The Italian Garden Café, 7 A402, London W2 2UE (https://www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/kensington-gardens/food-and-drink/the-italian-gardens-cafe )

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Leadenhall Market, EC3V 1LT A little bit pre-packaged, but a charming atmosphere

Bow Lane, EC4M 9EB Smart lane with shoe shops and several places to eat & drink

Gabriel’s Wharf, South Bank Home to a mix of independent shops, cafes, bars and restaurants. This arty enclave offers design-led shopping, from jewellery and ceramics to fair-trade furnishings and affordable artwork

Southbank Centre Book Market Browse for second-hand books under Waterloo Bridge.

PLACES TO VISIT

PLACES TO VISIT

The Monument, Fish St Hill, EC3R 8AH (www.themonument.info). Climb to the top for a great view.

Sky Garden, 1 Sky Garden Walk, EC3M 8AF (020 7337 2344, https://skygarden.london) Need to book tickets in advance for admission.

Temple of Mithras, Walbrook, City of London. Opening from late 2017. Google for more details once it’s open.

Tate Modern, Bankside, SE1 9TG (www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern )

Cabinet War Rooms, Clive Steps, King Charles St, SW1A 2AQ (020 7930 6961, www.iwm.org.uk/visits/churchill-war-rooms )

Boating on the Serpentine is open from April until October, north shore (020 7262 1330,

Adults – £12 for 1 hour or £10 for 30 minutes. Child (under 15) – £5 for 1 hour or £4 for 30 minutes. Family (2 adults and 2 children) – £29 for 1 hour or £24 for 30 minutes. Sadly no furry friends are allowed in the rowing boats or pedalos.

MORE TO DISCOVER

Walk: The Great Fire of London Trail: https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visit-the-city/walks/Documents/fire-of-london-self-guided-walk.pdf

Walk: City Gardens Trail: https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/green-spaces/city-gardens/Documents/city-gardens-leaflet.pdf

Walk: Modern Architecture trail: https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/visit-the-city/walks/Documents/designs-of-the-times-self-guided-walk.pdf

Walk: The Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Walk. PDF download available at https://www.royalparks.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/41392/diana_memorial_walk_leaflet.pdf

Read: Hidden City: The Secret Alleys, Courts and Yards of London’s Square Mile, by David Long

Read: London’s Royal Parks by Paul Rabbitts

Leave a Reply