Culture, learning and leafy suburbs

This walk is all about where and how the wealth of Bristol merchants was spent – on opulent homes, educating their children and cultural exploration.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 9.2 km (5.8 miles)

- Typical time: 2 ½ hours

- Height change: 53 metres

- Start & Finish: Redland Station (BS6 6QP)

- Terrain: The Downs can be muddy

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Cotham Gardens, Royal Fort Gardens, Clifton Park Gardens, Clifton Down, Durdham Down, University of Bristol Botanic Garden, Redland Green, Grove Park |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Avon, Redland Green spring |

| Stunning cityscape | St Michael’s Hill, The Observatory, Redmond Green |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | St Rupert Gate (1643) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | Royal Fort House (1761), The Observatory (18th C), The Engineers’ House (1831), Redland Parish Church (1742), Redland Court (1735) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Old Bristol Royal Hospital for Sick Children (1885), Bristol Grammar School (1870s), The Royal West of England Academy of Art (1857), The Victoria Rooms (1842), Channings Hotel (1882), Clifton College (1862), Christ Church (1841) |

| Industrial Heritage | Lead mining, Durdham Down |

| Modern (post-1918) | The H.H. Wills Physics Laboratory (1927), Clifton RC Cathedral (1973) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | Rosario’s Café, Primrose Café, Arch House Deli,

Café Retreat, University of Bristol Botanic Garden Café, The Cambridge Arms |

| Quirky Shopping | Clifton Arcade and Boyce’s Avenue |

| Places to visit | Royal West of England Academy of Arts, Bristol Zoo,

University of Bristol Botanic Garden |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Redland May Fair (early May), Foodies Festival on Durdham Down (mid-May), Bristol Walk Fest (May) – the UK’s largest urban celebration of walking, Bristol Balloon Fiesta (Aug); Bristol Doors Open Days, 7 -10 September 2017 |

City population: 449,300 (2017 est.)

Urban population: 617,000 (2011 census)

Ranking: 10th largest city in the UK (Wiki)

Date of origin: 11th century

‘Type’ of city: Maritime

City status: granted in 1542, when the Diocese of Bristol was founded

Some famous inhabitants of Redland, Clifton & Durdham Down: Sir Allen Lane, founder of Penguin (Cotham); Adolph Leipner, founder of the Botanic Garden (Redland); Henry Wills, engineer and philanthropist (Redland), Ellen Sharples, artist (Clifton), Sarah Guppy, inventor (Richmond Hill)

Notable city architects/planners: Charles Dyer (1794-1848) – Victoria Rooms, Christchurch, Engineers’ House; Charles Hanson (1817-1888) – Clifton College, St Paul’s Clifton.

In early April 1850 a group of architects gathered together at the Bristol Academy of Fine Arts and there they founded a new society – the Bristol Society of Architects. The Society’s original aim was to establish a code of practice for Bristol practitioners rather than a style or philosophy. They formed a professional body that strived to establish high standards of competence and behaviour.

Number of listed buildings ( the whole of Bristol): 4,600 listed, of which 100 are Grade I and 212 Grade II*.

Films shot here: Some People (1962 – Durdham Down Water Tower), The Inbetweeners (2014 – Clifton Bridge & Observatory), Starter for Ten (2006 – Royal York Crescent), There is a very useful set of movie and TV series maps at; http://www.filmbristol.co.uk/bristol-movie-maps

TV series shot here: The Young Ones, Being Human, Doctor Who, Skins

Estimated % of green space in the city (Eski): 29% (3rd out of Top 10 cities)

THE CONTEXT

This is a walk about where and how you spend your money once you have made it – delightful Victorian homes, seats of learning and cultural venues.

I love this quote by playwright J.B. Priestley, who sums it up rather neatly: “Bristol lives on, indeed arrives at a new prosperity, by selling us Gold Flake and Fry’s chocolate and soap and clothes and a hundred other things. As the smoke from a million Gold Flakes solidifies into a new Gothic Tower for the University; and the chocolate melts away only to leave behind it all the fine big shops down Park Street, the pleasant villas out at Clifton, and an occasional glass of Harvey’s Bristol Milk for nearly everybody.”

The two families alluded to, the Wills and the Fry families, were amongst the greatest benefactors of Bristol, from the 19th century to the early twentieth century, which also happens to be the era of the townscape that this walk passes through.

Henry Overton Wills (1828-1911), a key player in the growth of the family tobacco firm, became the first Chancellor of the University of Bristol, donating £100,000 (around £10 million in today’s money) to fund the charter. When he died in 1911, his estate was valued at £5,214,821, around £520 million in today’s money. The Fry family started in the confectionery business in the eighteenth century and started to make chocolate bars in the nineteenth. They were also key to the founding of the university and active in many other philanthropic activities, notably mental health.

Our route takes us past many opulent homes, seats of learning and cultural/scientific establishments, almost all of which were created and blossomed in that greatest of centuries, the nineteenth.

We pass by five seats of learning:

- The University of Bristol (1909, from a 1870s forerunner)

- Bristol Grammar School (moved in the 1870s to current site)

- Clifton High School (1877)

- Clifton College (1862)

- Redland High School for Girls (1882)

Five cultural/scientific establishments…

- Royal West of England Academy of Art (1854)

- The Victoria Rooms (1842)

- Bristol Zoo (1835)

- The Observatory (1820s)

- Botanic Garden (first founded 1882)

… and five churches…

- Cotham Parish Church (1842)

- Clifton Cathedral (pro-cathedral founded 1850)

- Christ Church Clifton (1841)

- Clifton Down Congregational Chapel (1868)

- Redland Parish Church (consecrated 1790

There is so much to see and enjoy.

THE WALK

Our walk starts from the attractive wrought iron bridge that crosses the train line above Redland Station. From here you get a good view of the quaint station, a stop on the Severn Beach Line, this station opening in 1897. The line has been featured by Thomas Cook as one of the scenic lines of Europe. We cross the line again as we cross Durdham Down, but you won’t know it as it’s in a tunnel beneath you, a mile-long descent to the Avon Gorge (unless that is, you detour to the NW of our path into The Gulley where you will come across a ventilation shaft alongside a path).

Our walk starts from the attractive wrought iron bridge that crosses the train line above Redland Station. From here you get a good view of the quaint station, a stop on the Severn Beach Line, this station opening in 1897. The line has been featured by Thomas Cook as one of the scenic lines of Europe. We cross the line again as we cross Durdham Down, but you won’t know it as it’s in a tunnel beneath you, a mile-long descent to the Avon Gorge (unless that is, you detour to the NW of our path into The Gulley where you will come across a ventilation shaft alongside a path).

As we stroll up Lovers Lane, Cotham Gardens is on our left. The walk upwards takes you through a long avenue of oak trees and Victorian black lamps which give a real feel of the history of the area. Cotham Gardens was one of the first public gardens created in the city on land donated to the council by the Fry family from the Cotham Tower Estate in 1879. The new park, already planted with many mature trees, was opened in 1881. The trustees of the owners of Redland Court also donated part of that property’s avenue and the lower part of Redland Grove in 1884. Over the next few years, a flagpole, bandstand, seats, shrubbery, walks and the Lovers Walk were added.

As we stroll up Lovers Lane, Cotham Gardens is on our left. The walk upwards takes you through a long avenue of oak trees and Victorian black lamps which give a real feel of the history of the area. Cotham Gardens was one of the first public gardens created in the city on land donated to the council by the Fry family from the Cotham Tower Estate in 1879. The new park, already planted with many mature trees, was opened in 1881. The trustees of the owners of Redland Court also donated part of that property’s avenue and the lower part of Redland Grove in 1884. Over the next few years, a flagpole, bandstand, seats, shrubbery, walks and the Lovers Walk were added.

Much of the layout of the southern end of the park survives with its intricate system of paths and trees intact. The lower part of the park is now dominated by a popular well-maintained play area but the overall impression of an attractive little urban park full of flowers, trees and shrubs remains.

Cotham, which we come to next, is an affluent, leafy inner suburb of Bristol, built in the mid-1800s. Cotham Church (slightly off our route) was built in 1842–43 by William Butterfield in a Gothic Revival style.

Cotham, which we come to next, is an affluent, leafy inner suburb of Bristol, built in the mid-1800s. Cotham Church (slightly off our route) was built in 1842–43 by William Butterfield in a Gothic Revival style.

Then we start heading down Cotham Grove as we aim towards the University. The Cotham Park Obelisks are rather a surprise. These 18th-century obelisks were originally gate piers to Cotham Lodge which was demolished in 1846.

The Cotham Park Obelisks are rather a surprise. These 18th-century obelisks were originally gate piers to Cotham Lodge which was demolished in 1846.

Southwell St runs alongside St Michael’s Hospital, a brutalist pile opened in 1974.  On our right at the start of the street we spotted an interesting old school building – Kingsdown Council School, 1910 – now, like much else around here, part of the University.

On our right at the start of the street we spotted an interesting old school building – Kingsdown Council School, 1910 – now, like much else around here, part of the University.

The Old Bristol Royal Hospital for Sick Children was opened in 1886 and gained ‘Royal’ status by Queen Victoria in 1897. With the opening of a new, bigger new site in recent years, the building is now also part of the university.

The Old Bristol Royal Hospital for Sick Children was opened in 1886 and gained ‘Royal’ status by Queen Victoria in 1897. With the opening of a new, bigger new site in recent years, the building is now also part of the university.

St Michael’s Hill, which we look down, offers sweeping views of the city centre; it was the main route from medieval Bristol towards Wales; visually it is a happy mix of C17th-19th-century houses, framing the view of the city.

St Michael’s Hill, which we look down, offers sweeping views of the city centre; it was the main route from medieval Bristol towards Wales; visually it is a happy mix of C17th-19th-century houses, framing the view of the city.

The area we are now entering at  Prince Rupert’s Gate is Bristol’s main campus, called the “University Precinct”.

Prince Rupert’s Gate is Bristol’s main campus, called the “University Precinct”.

The exquisite Royal Fort House was constructed on the site of Civil War fortifications, which had two bastions on the inside of the lines and three on the outside. It was the strongest part of the defences of Bristol, designed by Dutch military engineer Sir Bernard de Gomme.The Fort was designed as the western headquarters of the Royalist army under Prince Rupert. Royalists retreated into the fort when the Parliamentarians had broken through the lines in the siege of 1645, before eventually surrendering to Cromwell’s forces.

The exquisite Royal Fort House was constructed on the site of Civil War fortifications, which had two bastions on the inside of the lines and three on the outside. It was the strongest part of the defences of Bristol, designed by Dutch military engineer Sir Bernard de Gomme.The Fort was designed as the western headquarters of the Royalist army under Prince Rupert. Royalists retreated into the fort when the Parliamentarians had broken through the lines in the siege of 1645, before eventually surrendering to Cromwell’s forces.

The design of the mid-eighteenth-century house by James Bridges, for Thomas Tyndall KCB, was a compromise between the separate designs of architects Thomas Paty, John Wallis and himself. This led to different classical styles: Baroque, Palladian and Rococo, for three of the facades of the house. It was built between 1758 and 1761, by Thomas Paty with plasterwork by Thomas Stocking. Pevsner describes it as ‘Bristol’s finest Georgian villa’.

Humphry Repton, the great landscape designer, was employed from 1799 to landscape the gardens which formed a small part of Tyndall’s Park, which extended to Whiteladies Road in the west, Park Row in the south and Cotham Hill to the north. Over the years, large parts of the park were sold for housing development, and the site for the Bristol Grammar School, purchased in 1877, and only a small part of the original area remains, as Royal Fort Gardens.

The garden is now widely used for student activities and relaxing. It contains a small pond, specimen trees and a mirror maze, called “Follow Me”, designed by the internationally recognised artist Jeppe Hein. In 2016 a new installation called ‘Hollow’ was produced by Katie Paterson which brings together samples taken from 10,000 species of wood that grow throughout the world.

The garden is now widely used for student activities and relaxing. It contains a small pond, specimen trees and a mirror maze, called “Follow Me”, designed by the internationally recognised artist Jeppe Hein. In 2016 a new installation called ‘Hollow’ was produced by Katie Paterson which brings together samples taken from 10,000 species of wood that grow throughout the world.

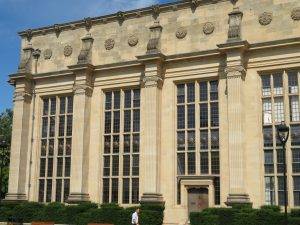

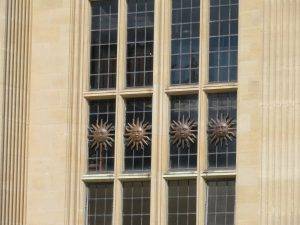

The H.H. Wills Physics Laboratory stands opposite Royal Fort House. Designed by Sir George Oatley, it was built between 1921 and 1927 and took its inspiration from the 16th century Kirby Hall in Northamptonshire. Oatley drew up plans for three more towers forming a quadrangle around Royal Fort House, but these were never built.

The H.H. Wills Physics Laboratory stands opposite Royal Fort House. Designed by Sir George Oatley, it was built between 1921 and 1927 and took its inspiration from the 16th century Kirby Hall in Northamptonshire. Oatley drew up plans for three more towers forming a quadrangle around Royal Fort House, but these were never built.

The Bristol Grammar School is mainly built in classic Victorian Gothic style. The move to the present site in the 1870s followed a massive shake-up in education in England. Government commissioners came to Bristol to reorganise things and decreed that the school should be funded by taking money from various charitable funds and bequests in the city over the years.

The Great Hall and the original surrounding buildings were designed by local architects Foster & Wood, one of the most successful firms in Victorian Bristol. The Great Hall was pretty much the whole school when it started at this site; the room is 140 feet long and 50ft wide and it was used for the teaching of all the boys there apart from the oldest. It was meant to accommodate up to 16 separate classes; and the masters’ chairs, with their wooden canopies, are still in place along the walls.

The Royal West of England Academy of Art (1854-7) was designed by JH Hirst with interiors by Charles Underwood. It was the first art gallery to be established in Bristol, financed by a well-known group of artists in Bristol, known as the Bristol Society of Artists and a bequest of £2,000 in the will of Ellen Sharples, an artist who spent the later years of her life in Clifton. The Academy soon became an important and well-regarded art institution. Early patrons included Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Prince Albert, the Prince Consort.

The Victoria Rooms, designed by Charles Dyer and constructed between 1838 and 1842 in Greek revival style, were mainly used for private balls and large banquets, such as that to celebrate the opening of the Clifton Suspension Bridge in 1864.

The Victoria Rooms, designed by Charles Dyer and constructed between 1838 and 1842 in Greek revival style, were mainly used for private balls and large banquets, such as that to celebrate the opening of the Clifton Suspension Bridge in 1864.

But in 1874 they hosted what was described as a College of Science and Literature for the West of England and South Wales, which became University College, Bristol, an educational institution which existed from 1876 to 1909. It was the predecessor institution to the University of Bristol, which gained a Royal Charter in 1909. The university was able to apply for a royal charter due to the financial support of the Wills and Fry families, who made their fortunes in tobacco plantations and chocolate, respectively. Sir Winston Churchill became the university’s third chancellor in 1929, serving the university in that capacity until 1965. This direct link with Bristol made him particularly sensitive to the wartime bombing. He was reportedly in tears on visiting Bristol after a bombing raid in 1941, saying: “They have such confidence. It is a grave responsibility”.

In 1920, George Wills bought the Victoria Rooms and endowed them to the university as a Students’ Union. They now house the university’s Department of Music.

Next, we climb the rather charming Richmond Hill. Then along the Pembroke Rd and past Channings Hotel, built in 1879-82 by Thomas Nicholson. In the words of Pevsner ‘gloriously brash and pompous…(with)… two competing facades, all angles and bays, overwhelmed with incidental carving.’

Channings Hotel, built in 1879-82 by Thomas Nicholson. In the words of Pevsner ‘gloriously brash and pompous…(with)… two competing facades, all angles and bays, overwhelmed with incidental carving.’

The Roman Catholic Clifton Cathedral, designed by R.J. Weeks, was completed in 1973, replacing the 1850s pro-cathedral just south of Park Place (now converted into offices and residential).

The Roman Catholic Clifton Cathedral, designed by R.J. Weeks, was completed in 1973, replacing the 1850s pro-cathedral just south of Park Place (now converted into offices and residential).

You will love or hate the architecture of this vast concrete structure. Personally, I love it, as a celebration of concrete (‘Bristol’s sermon in concrete’) and a unique internal space, the architect’s innovative response to the requirements set down by the Second Vatican Council, which decreed that the congregation should all have a good view of the altar; accordingly, the sanctuary is hexagonal to allow the 1,000-capacity congregation a close and clear view of the altar, and there are no windows within the congregation’s line of sight of the altar. Natural roof lights provide daytime lighting, ensuring that the sanctuary area remains the focus of the service.

And no -one can say that a lot of money was squandered on it. Coming in at a final cost of only £600,000, it has been described as the ‘ecclesiastical bargain of the 1970s’. Mind you, it has been plagued by leaks ever since it opened, and buckets collecting rainwater have been a familiar sight for worshippers over the years. A major refurbishment project has just been completed which, guess what – cost £600,000 in its first phase. Maybe the building wasn’t such a bargain after all.

Worcester Terrace is a very fine Grade II* star terrace of 14 houses, dating from 1851-3, by Charles Underwood. A complete terrace with much of its iron railing complete, and finely situated on a raised Pennant pavement: a ‘… very good Late Grecian terrace’ according to Pevsner. There is also a shared private garden for Worcester Terrace residents. They take it very seriously, having a membership charge of £400 a year (that’s a lot, the nearby Clifton Park Gardens is £55) and doesn’t include mowing as part of the package, as I notice there is also a residents’ mowing rota (mind you, that’s usually the most fun job).

Worcester Terrace is a very fine Grade II* star terrace of 14 houses, dating from 1851-3, by Charles Underwood. A complete terrace with much of its iron railing complete, and finely situated on a raised Pennant pavement: a ‘… very good Late Grecian terrace’ according to Pevsner. There is also a shared private garden for Worcester Terrace residents. They take it very seriously, having a membership charge of £400 a year (that’s a lot, the nearby Clifton Park Gardens is £55) and doesn’t include mowing as part of the package, as I notice there is also a residents’ mowing rota (mind you, that’s usually the most fun job).

5-minute detour: Clifton College was founded in 1862 by a group of “professional men and gentry to provide Bristol with an elite school on the model of Rugby”.

5-minute detour: Clifton College was founded in 1862 by a group of “professional men and gentry to provide Bristol with an elite school on the model of Rugby”.

John Percival, after whom the road was named (and a good point to reach for a view of the school), was its first headmaster. At his interview, the 27-year old Percival was told by one council member that he was very young, while another remarked that he was unmarried.

“A few years will correct the former,” he is said to have replied, “and a few weeks the latter.” Percival was true to his word – within a fortnight, and after a two-day honeymoon in Clevedon, the head brought home his bride. And by the time he left the College in 1879 to become Master of an Oxford college, the school had risen in numbers to 600 and established a national reputation.

Percival was also an early mover in helping to get a university established in Bristol. In 1872, he wrote to the Oxford colleges observing that the provinces lacked a university culture. The following year he produced a pamphlet called ‘The Connection of the Universities and the Great Towns’, which was well received by Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol College, Oxford. Jowett was to become a significant figure, both philosophically and financially, in the establishment of University College, Bristol.

The splendid Victorian Gothic college buildings were designed by Charles Hansom (the brother of Joseph Hansom). The ground that we are looking across is known as The Close; it has an important place in the history of cricket, witnessing 13 of WG Grace’s first-class hundreds for Gloucestershire CC in the County Championship. He lived in Bristol (we pass his house on the Bristol 1 walk) and his children attended the college.

The splendid Victorian Gothic college buildings were designed by Charles Hansom (the brother of Joseph Hansom). The ground that we are looking across is known as The Close; it has an important place in the history of cricket, witnessing 13 of WG Grace’s first-class hundreds for Gloucestershire CC in the County Championship. He lived in Bristol (we pass his house on the Bristol 1 walk) and his children attended the college.

Clifton College has had lots of famous old boys, ranging from Field Marshal Douglas Haig to John Cleese. Of most interest to walkers perhaps was the politician, Leslie Hore-Belisha who introduced the driving test, the Highway Code and the eponymous beacon that started to make life so much better for us urban ramblers.

Then we walked along Wyvyan Terrace (1833–47) and past Clifton Park Gardens. The residents describe their garden as “a corner of the countryside in the heart of Clifton”. Membership is open to anyone living in the neighbourhood, but not to urban ramblers from afar alas. They do, however, have jazz picnics on Sundays in June, which might be worth keeping an eye out for.; for if you come with colourful cushions, rugs and exquisite picnics and something sparkling you will no doubt be admitted.

Christ Church (1841) is a solidly reassuring mid-Victorian church, designed by Charles Dyer, who also designed the Victoria Assembly Rooms and the Engineer’s House, which we will pass shortly, another well-known Bristol landmark.

Christ Church (1841) is a solidly reassuring mid-Victorian church, designed by Charles Dyer, who also designed the Victoria Assembly Rooms and the Engineer’s House, which we will pass shortly, another well-known Bristol landmark.

Pevsner is critical of its mundane interior, seeing it as a function of ‘chilly Anglicanism’ and cites John Betjeman’s poem ‘Bristol and Clifton’, in which this is the protagonist’s local church:

“Seeing I have some knowledge of finances

Our kind Parochial Church Council made

Me People’s Warden, and I’m glad to say

That our collections are still keeping up.

The chancel has been flood-lit, and the stove

Which used to heat the church was obsolete.

So now we’ve had some radiators fixed

Along the walls and eastward of the aisles;

This last I thought of lest at any time

A Ritualist should be inducted here

And want to put up altars. He would find

The radiators inconvenient.

Our only ritual here is with the Plate;

I think we make it dignified enough.

I take it up myself, and afterwards,

Count the Collection on the vestry safe.”

Clifton and Durdham Downs – ‘for ever hereafter’

For many centuries, the commoners of the two medieval manors of Clifton and Henbury had the right to graze their animals on Clifton and Durdham Downs. But by the mid-nineteenth century grazing was declining as the city expanded and development pushed in at the edges of the common land. Mines and quarries also scarred the Downs as well as the Avon Gorge.

In 1856 the Society of Merchant Venturers, owners of Clifton Down since the late seventeenth century, promised: “to maintain the free and uninterrupted use of the Downs”. The following year Bristol City Council purchased two small properties in Stoke Bishop, together with one of the few remaining commoner’s rights to graze animals on Durdham Down. In the spring of 1858, the City of Bristol turned out sheep stamped ‘CB’, keeping alive the medieval rights of pasturage and making further development more difficult.

In 1856 the Society of Merchant Venturers, owners of Clifton Down since the late seventeenth century, promised: “to maintain the free and uninterrupted use of the Downs”. The following year Bristol City Council purchased two small properties in Stoke Bishop, together with one of the few remaining commoner’s rights to graze animals on Durdham Down. In the spring of 1858, the City of Bristol turned out sheep stamped ‘CB’, keeping alive the medieval rights of pasturage and making further development more difficult.

Then, in equal partnership, the council and the Merchant Venturers promoted The Clifton and Durdham Downs (Bristol) Act, 1861. This act allowed the council to purchase Durdham Down. It preserved the Downs for us all ‘for ever hereafter’. And it set up the method of management that continues today: The Downs Committee made up equally of councillors and Merchant Venturers under the chairmanship of The Lord Mayor. What an incredible success story.

Our first spot is the obelisk on Christchurch Green. The obelisk and the sarcophagus were originally in the rear garden of Manilla Hall and moved here in 1883 when the house was demolished. The Hall had been built by General Sir William Draper with the £5,000 bounty he received from the East India Company for his capture in 1762 of the Spanish city of Manila in the Philippines. He erected the sarcophagus in 1766 in memory of the officers and men of the regiment he had himself formed. Do read the inscriptions – a moving history of India and empire.

Our first spot is the obelisk on Christchurch Green. The obelisk and the sarcophagus were originally in the rear garden of Manilla Hall and moved here in 1883 when the house was demolished. The Hall had been built by General Sir William Draper with the £5,000 bounty he received from the East India Company for his capture in 1762 of the Spanish city of Manila in the Philippines. He erected the sarcophagus in 1766 in memory of the officers and men of the regiment he had himself formed. Do read the inscriptions – a moving history of India and empire.

Observatory Hill has an Iron Age earthworks of double banks and ditches upon it. With the steep cliffs nearby, it was a natural defensive position. At the highest point is The Observatory, an 18th-century windmill, originally used for grinding corn and later converted to the grinding of snuff. It was recreated as an observatory in the 1820s, complete with telescopes and a camera obscura, a forerunner of the modern camera.

Observatory Hill has an Iron Age earthworks of double banks and ditches upon it. With the steep cliffs nearby, it was a natural defensive position. At the highest point is The Observatory, an 18th-century windmill, originally used for grinding corn and later converted to the grinding of snuff. It was recreated as an observatory in the 1820s, complete with telescopes and a camera obscura, a forerunner of the modern camera.

The mile-long Clifton Down road forms a perfect continuum of domestic architecture from the 1830s to the 1870s, on the most substantial scale possible while maintaining an essentially suburban character. The Engineers’ House is one of the most notable, built in 1831 by Charles Dyer for Charles Pinney, who became mayor of Bristol, serving during the Reform Bill Riots of 1831.

The mile-long Clifton Down road forms a perfect continuum of domestic architecture from the 1830s to the 1870s, on the most substantial scale possible while maintaining an essentially suburban character. The Engineers’ House is one of the most notable, built in 1831 by Charles Dyer for Charles Pinney, who became mayor of Bristol, serving during the Reform Bill Riots of 1831.

Alderman Thomas Proctor’s fountain, which we spotted just before we got to the junction, was erected to commemorate the “liberal gift of certain rights over Clifton Down made to the citizens of Bristol by the Society of Merchant Venturers” under the Downs Act of 1861. More important, originally, was its function as a drinking fountain. Alderman Proctor, himself, stated that it provided sufficient water for the “thousands who avail themselves of the downs on the Sunday afternoon and evening… but to meet any extra demand, my man takes out a number of half-pint mugs.” In 1872, when the fountain was completed, Proctor was living in the only detached house overlooking the Triangle – all the others are very grand semi-detached mansions. In 1874 he presented it to the city for use as the Mayor’s Mansion House.

Alderman Thomas Proctor’s fountain, which we spotted just before we got to the junction, was erected to commemorate the “liberal gift of certain rights over Clifton Down made to the citizens of Bristol by the Society of Merchant Venturers” under the Downs Act of 1861. More important, originally, was its function as a drinking fountain. Alderman Proctor, himself, stated that it provided sufficient water for the “thousands who avail themselves of the downs on the Sunday afternoon and evening… but to meet any extra demand, my man takes out a number of half-pint mugs.” In 1872, when the fountain was completed, Proctor was living in the only detached house overlooking the Triangle – all the others are very grand semi-detached mansions. In 1874 he presented it to the city for use as the Mayor’s Mansion House.  You can see its white conservatory from here.

You can see its white conservatory from here.

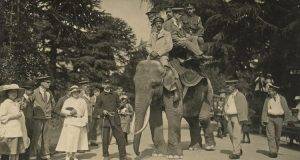

Bristol Zoo was founded in 1835 by Henry Riley, a local physician, who led the formation of the Bristol, Clifton and West of England Zoological Society. Riley, and several other prominent local individuals gathered with the mission to facilitate “the observation of habits, form and structure of the animal kingdom, as well as affording rational amusement and recreation to the visitors of the neighbourhood.” Shareholders at the time included several famous Bristolians, including Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Bristol Zoo’s situation close to a port greatly helped with the acquisition of animals when it first opened.

Bristol Zoo was founded in 1835 by Henry Riley, a local physician, who led the formation of the Bristol, Clifton and West of England Zoological Society. Riley, and several other prominent local individuals gathered with the mission to facilitate “the observation of habits, form and structure of the animal kingdom, as well as affording rational amusement and recreation to the visitors of the neighbourhood.” Shareholders at the time included several famous Bristolians, including Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Bristol Zoo’s situation close to a port greatly helped with the acquisition of animals when it first opened.

It still has many of the original landscape gardens by Richard Forrest. And, like its earlier London counterpart, it also has several original buildings which have been praised for their architectural quirks, despite being unsuitable for the care of animals; the (former) Giraffe House joins the main entrance lodge and the south gates on Guthrie Road as a Grade II listed building. And the old Monkey Temple, resembling a southern-Asian temple, is now home to an exhibit called “Smarty plants”, an interactive exhibit which shows how plants use and manipulate animals to survive.

There are remnants of an Iron Age or Roman field system between Bristol Zoo and Ladies Mile, exactly on our route. The Roman road from Bath to Sea Mills crossed the Downs near Stoke Road, and a short length is visible as a slightly raised grassy bank. Gail Boyle writes: “If you stand here you can actually see that very shallow hump that shows you where the Roman road is. It’s a stretch that exists now for about 140 metres, about 25 metres wide. If you want to see it properly you have to come out very early in the morning so the shadow is thrown by the hump, or when it’s been frosting because the frost will disappear when the sun comes up, you can see it highlighted in the frost or the snow. But it is actually quite difficult to detect.” To see exactly where it went, take a look at http://www.thedowns150.org.uk/2012/01/the-roman-road/

There are remnants of an Iron Age or Roman field system between Bristol Zoo and Ladies Mile, exactly on our route. The Roman road from Bath to Sea Mills crossed the Downs near Stoke Road, and a short length is visible as a slightly raised grassy bank. Gail Boyle writes: “If you stand here you can actually see that very shallow hump that shows you where the Roman road is. It’s a stretch that exists now for about 140 metres, about 25 metres wide. If you want to see it properly you have to come out very early in the morning so the shadow is thrown by the hump, or when it’s been frosting because the frost will disappear when the sun comes up, you can see it highlighted in the frost or the snow. But it is actually quite difficult to detect.” To see exactly where it went, take a look at http://www.thedowns150.org.uk/2012/01/the-roman-road/

Next up is the University of Bristol Botanic Garden. In 1882 Bristol University College awarded their Lecturer of Botany, Adolf Leipner, a grant of £15 for the purpose of laying out a botanic garden. Leipner raised a further £89 and the garden was built on waste ground near to Royal Fort House. Later the garden moved to a site adjacent to Tyndall Avenue which became known as Hiatt Baker Garden.

The current site has only been in existence in 2005; on the plus side, that has allowed it to do things very differently, for example arranging plants by evolutionary progression and grouping. It’s a lovely spot to take a break, and we found we could exit out the back which meant that we didn’t have to retrace our steps!

The current site has only been in existence in 2005; on the plus side, that has allowed it to do things very differently, for example arranging plants by evolutionary progression and grouping. It’s a lovely spot to take a break, and we found we could exit out the back which meant that we didn’t have to retrace our steps!

Once across Durdham Down, we are entering Redland, best known today for its vast amounts of student accommodation. There are different views of the origin of the name Redland. One source says that in the 11th century it was known as Rudeland, possibly from Old English rudding, meaning ‘cleared land’. Another source points to a mention in 1209 as Thriddeland, probably meaning the third part of an estate’. Yet another source refers to a mention in 1230 of Rubea Terra and a later mention as la Rede Londe, derived from the red colour of the soil. Take your pick.

Redland Green is a slip of a park, concave in shape and linear. The day we went there were two young men doing endurance runs up the slopes…and a couple of dog walkers idly chatting away. A gentle reminder of just how important urban green spaces are to our lives.

Redland Green is a slip of a park, concave in shape and linear. The day we went there were two young men doing endurance runs up the slopes…and a couple of dog walkers idly chatting away. A gentle reminder of just how important urban green spaces are to our lives.

Metford Rd Allotments are a glorious mass of horticultural productivity on our left. Bristol is the third larger provider of allotments in the country with 4,100 plots spread out over 104 sites, some with hundreds of plots and others just a handful. The council says waiting times can be anywhere from one year to five years depending on the location.

At the end of the allotments north of the stream is a wonderful wild green place, the Metford Road Community Orchard. It is steep, full of all kinds of fruit trees and bushes, has glorious views, and is home to masses of butterflies, insects and frogs. The outcome of a valiant community effort.

Redland Parish Church dates back to 1742, built, its plasterwork by Thomas Paty, as a private chapel for the local manor house, Redland Court, which is now Redland High School. It eventually became the parish church of Redland as the population of the district grew.

Redland Parish Church dates back to 1742, built, its plasterwork by Thomas Paty, as a private chapel for the local manor house, Redland Court, which is now Redland High School. It eventually became the parish church of Redland as the population of the district grew.

Redland Court, which is now Redland High School, was built between 1732 and 1735 by John Strachan, for John Cossins, on the site of an Elizabethan House that previously stood on the same site. It is an impressive Grade II* listed building.

Redland Court, which is now Redland High School, was built between 1732 and 1735 by John Strachan, for John Cossins, on the site of an Elizabethan House that previously stood on the same site. It is an impressive Grade II* listed building.

And then a final stroll down Grove Park and you are back at the station. Wow.

THE ROUTE

- Head left out of the station up South Rd, then first left across the railway and along Lovers’ Walk; continue through Cotham Gardens, exiting near the end into Cotham Grove

- Follow Cotham Grove, crossing Archfield Rd into the narrow Pitch Lane, then into Cotham Rd heading south; this becomes Montague Place, then Hotfield Rd

- Turn right just before St Michael’s Hospital into Southwell St, coming out onto St Michael’s Hill opposite the old Children’s Hospital

- Turn left down the hill, then shortly right into Royal Fort Rd and through the arch into the University grounds

- Head left after Royal Fort House and take a circuit round Convocation Walk, exiting the main university area at Tyndall Avenue

- Cross Woodland Rd and head down Elton Rd, then Elmdale Rd to reach Queens Rd

- Cross straight over and climb Richmond Hill, over a mini-roundabout into Pembroke Rd

- On reaching Clifton Cathedral, go through it or head down Worcester St, turning left into Worcester Terrace, proceeding along the raised pavement to College Rd (5-minute detour right here up College Rd to see Clifton College)

- Turn left here, cross Clifton Park Rd, with the Clifton Park Gardens on your left

- Turn right along Christchurch Rd and you reach Christ Church Clifton

- Head W across Clifton Down and up to the Clifton Observatory overlooking the Clifton Suspension Bridge

- Follow the route initially above the gorge, then it cuts back into a tree-lined avenue that runs parallel with Clifton Down Rd

- Where it meets Bridge Valley Rd, cross over on to Clifton Down, heading up a footpath onto the common, following this parallel to the Clifton Down Rd until you are nearly parallel with the zoo

- At this point head up the slope away from the zoo, and when you reach the next path, cross over onto the grass heading due north; on reaching the Ladies Mile, cross over and you will find a track on the other side heading N along an avenue of trees until it reaches Rockleaze; follow Downleaze heading NE until it reaches Stoke Hill

- Once in Stoke Hill, take the first right up Stoke Park Rd until you reach the University of Bristol Botanic Gardens (please check opening times, no way through otherwise); pass through the gardens (admission payment necessary) and exit into Hollybush Lane

- Cross Saville Rd onto Durdham Down and head E to exit into Clay Pit Rd, which then becomes Belvedere Rd

- Turn right at the end along The Glen, then right into Blenheim Rd and shortly left into the Quadrant; then right into Coldharbour Rd and shortly left into St Oswald’s Rd

- After a few yards, follow the path left into Redland Green and then head SE down the park to the exit in Redland Green Rd

- Go past the entrance to Redland Parish Church, keeping to the left of the green and joining Woodstock Rd; then take the second right into Clarendon Rd, which comes down to Redland Grove

- Turn left on reaching Redland Grove, cross the pedestrian crossing and then walk S along the left-hand side of Grove Park to reach South Rd and the station.

PIT STOPS

Rosario’s Café, 99 Queens Rd, Bristol BS8 1LW (0117 317 9806). Characterful, Sicilian food and drinks

Primrose Café, 1, The Clifton Arcade, Boyce’s Ave, Bristol, BS8 4AA (0117 946 6577, www.primrosecafe.co.uk) The sort of café it’s very hard to pass by without going in.

Arch House Deli, Boyce’s Ave, Bristol, BS8 4AA (0117 974 1166, www.archhousedeli.com) Sit in the café or put together a mini-picnic to eat on Clifton Down.

Café Retreat, Stoke Road, Durdham Down, Bristol, BS9 1FG (0117 923 8186, by the water tower)

The Cambridge Arms, Coldharbour Rd, Redland BS6 7JS (0117 973 9786, www.cambridgearms.co.uk) A great pub with good pub food and a beer garden

QUIRKY SHOPPING

Clifton Arcade (BS8 4AA) and Boyce’s Avenue (BS8 4ET, just south of Clifton Down). Originally opened in 1878, it later fell into disuse but has recently been restored and now houses a community of small shops. An interesting assortment, from jewellery, vintage furniture, pre-loved clothes, a hairdressers and The Boutique Bakehouse.

PLACES TO VISIT/THINGS TO DO

Royal West of England Academy of Arts, Queen’s Road, Clifton, BS8 1PX (0117 973 5129, www.rwa.org.uk)

Bristol Zoo, College Rd, Clifton, Bristol BS8 3HA (0117 428 5300, www.bristolzoo.org.uk)

University of Bristol Botanic Garden, Stoke Park Rd, Stoke Bishop, BS9 1JG (0117 331 4906, www.bristol.ac.uk/botanic-garden)

MORE TO DISCOVER

Follow: A History trail around Clifton Down https://www.bristol.gov.uk/documents/20182/32863/Clifton+Down+History+Trail/f4df2d0b-46aa-49e3-ac96-6cf7eaf14bf1

Help Protect our Parks: “Bristol City Council’s published budget proposals show that they will stop funding our parks from April 2019 (a budget cut of £4.5Mn), relying instead on revenue generated from parks events and other outside sources. Bristol Parks Forum believes this is impossible to achieve in such a short timescale. Many other big cities are exploring this option, some have already decided it simply won’t work; this was also the conclusion of last year’s Select Committee of the House of Commons. Unless Bristol Parks find ways to replace all this funding with additional income there is a high risk that there will be a drastic cut in the maintenance of parks that will lead to a downward spiral of reduced use and increased anti-social behaviour as standards fall.” Support the cause by emailing the council.

Read: Pevsner City Guides, Bristol

Leave a Reply