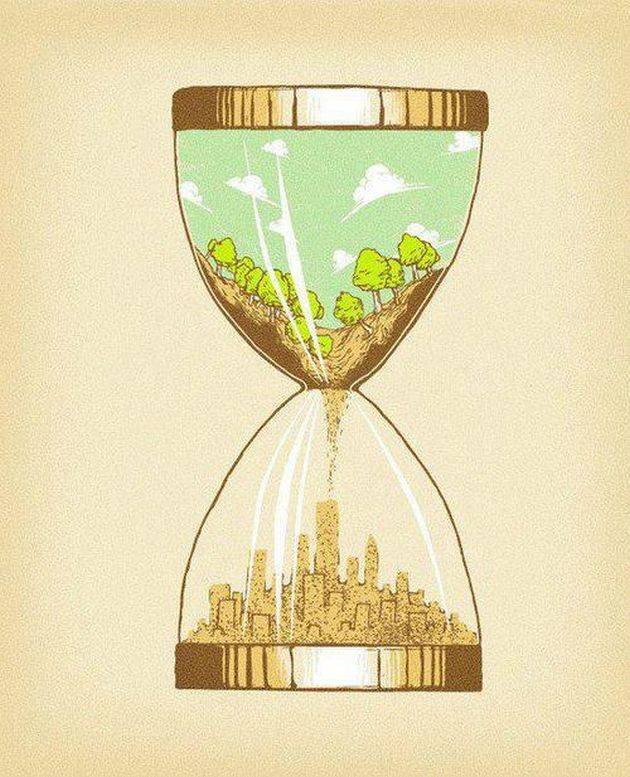

The green and walkable city is back (after a couple of millennia)

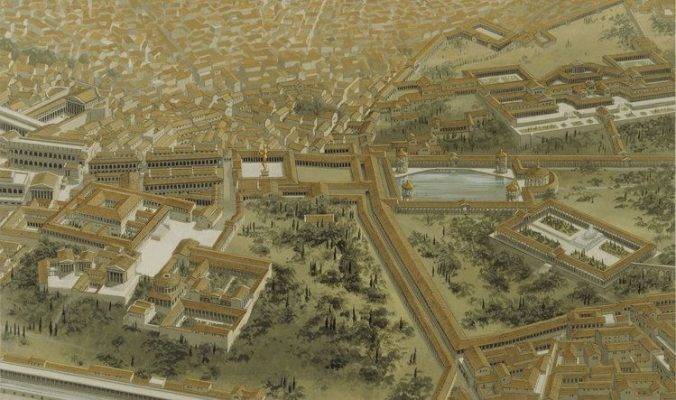

The Romans were the first civilization to recognise the benefits of rural features within a city; from the Campus Martius that was transformed into plush parkland by Augustus, incorporating lakes and space for recreation & leisure; to the ‘horti’ (urban villas within a park) created by wealthy Romans; reaching its zenith in Nero’s ‘Domus Aurea’, which embraced nature on an altogether grander scale and literally brought the countryside to Rome. Nero’s palatial grounds incorporated the cultivated environment and untamed wild simultaneously, housing a multitude of wild and domestic animals, vineyards and tilled lands, offset by the rural seclusion of woods and open ground.

The desirability of nature in Rome was seen as twofold: as a mark of civilization and as a promoter of health & well-being. They coined the phrase ‘rus in urbe’ to describe it.

‘Rus in Urbe’ – the country in the city – has been used in Britain ever since to refer to country features created in towns or cities. A thousand newspaper articles today use it as shorthand to describe a desirable new green feature that is proposed or that needs protection in a city. It has become the ‘go to’ phrase of the green space cognoscenti.

The invention of the London square

In Britain, the benefit of rural space in towns was recognised as early as the 17th century. In 1618 a Commission on Buildings was established to oversee the development of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, one of the first planned green spaces in the country. Before that the only green spaces had been royal hunting parks, for example Hyde Park and Richmond Park.

The aim of the Commission on Buildings was to ensure that Lincoln’s Inn Fields was set out with “faire and goodlye walks, (which) would be a matter of great ornament to the Citie, pleasure and freshness for the health and recreation of the Inhabitants thereabout, and for the sight and delight of Embassadors and Strangers coming to our Court and Cittie, and a memorable worke of our tyme for all posteritie.”

The desirability of ‘rus in urbe’ – creating the illusion of countryside within a city – was soon taken up with enthusiasm by the British aristocracy as they started to create estates in London. It was St James’s Square which was first enclosed by Act of Parliament in 1726, allowing the residents ‘to clean, repair, adorn and beautify the same, in a becoming and graceful manner’. Charles Bridgeman, the landscape gardener, was employed to create the ‘illusion’. Many squares followed, almost all of which are still in existence today, allowing wealthy residents the chance for a spot of tranquillity, fresh air and a reminder of their country estate.

As Todd Longstaffe-Gowan wrote, in his book ‘The London Square’, “Modern-day London abounds with a multitude of gardens, enclosed by railings and surrounded by houses, which attest to the English love of nature. These green enclaves are among the most distinctive and admired features of the metropolis and are England’s greatest contribution to the development of European town planning and urban form. They epitomise the classical notion of ‘rus in urbe’, the integration of nature within the urban plan – a concept that continues to shape cities to this day.”

The pernicious effect of industrialisation on cities

But the square was an enclave and escape from the city rather than being a part of it, and was usually only accessible to its wealthy residents. As industrialisation took hold in the 19th century, so the gap between town and country grew greater, and the dividing lines became still more entrenched.

In response, the Romantic Movement of the early 19th century drew a sharp juxtaposition between the pastoral idyll of the countryside and the squalor and dissoluteness of the city; and in so doing undoubtedly exaggerated the attributes of each.

Wordsworth famously expressed his vision of a pastoral idyll in ‘Lines written a few Miles above Tintern Abbey’:

“Therefore am I still

A lover of the meadows and the woods,

And mountains; and of all that we behold

From this green earth…”

Conversely the poetry of the city is so often about the downtrodden underclasses, as in Blake’s London (1793):

“I wandered through each chartered street,

Near where the chartered Thames does flow,

A mark in every face I meet,

Marks of weakness, marks of woe…”

In much the same way, The English novels of the nineteenth century also emphasised the squalor, poverty and licentiousness of 19th century cities, for example in the novels of Elizabeth Gaskell and Thomas Hardy.

Sadly the statistics of the times bear out this pessimistic view. The Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain (1842) showed that a typical country farmer lived twice as long (41 years) as a city shopkeeper (20 years).

The drive of the non-conformists to create better cities

But from about this time a group of reformers begun to emerge, both philanthropists and politicians, who wanted to improve the lot of the city dweller, through better sanitation and the provision of open spaces (or a city’s ‘green lungs’ as they were already being referred to, a term coined by William Pitt the Elder).

These men (the likes of Chamberlain in Birmingham, Cowen in Newcastle, Baines in Leeds, Roebuck in Sheffield and Engels in Manchester) also expressed much more positive views about cities than those typical of the literature of the time. They (in Asa Briggs words) ‘did not argue on the defensive. They persistently carried the attack into the countryside, comparing contemptuously the passive with the active, the idlers with the workers, the landlords with the businessmen, the voluntary initiative of the city with the torpor and monotony of the village, and urban freedom with rustic feudalism.’

Non-conformism played a huge role in helping to transform cities. Non-conformists were behind many of the institutional initiatives of the 19th century – schools, libraries, parks and cemeteries. Furthermore, they were instrumental to much of the campaigning for social and political reform that has subsequently formed the bedrock of modern civil liberties.

The emergence of the public parks movement

In 1833 The Report of the Select Commission on Public Walks was published, advocating the provision of public parks in cities as an important factor in improving urban living standards. It noted:

‘With a rapidly increasing population, lodged, for the most part in narrow courts and confined streets, the means of occasional exercise and recreation in the fresh air are everyday lessened, as enclosures take place and buildings spread themselves on every side. A few towns have been fortunate in this respect from having some open space in their immediate vicinity…yet even at these places…the accommodation is inadequate to the wants of the increasing number of people.’

After seven years of campaigning, Manchester set up the Committee for Public Walks, Gardens & Playgrounds in 1840; and in 1846 three parks were opened — Queen’s Park and Philips Park, in Manchester, and Peel Park in Salford – the start of the municipal park revolution. By the end of the century, every city had at least one municipal park.

The literature finally catches up

Meanwhile, in literature, there were signs too of a new attitude towards the representation of cities and the humanity of their inhabitants.

Charles Dickens was a great lover of London, turning the beauty and squalor of the city into universal narratives that struck a chord with his readers. ‘Sketches by Boz’ is a collection of articles penned by his journalistic ‘alter ego’, who he describes as a ‘speculative pedestrian’. Dickens wanted to get to know humanity up close, foot to foot, nose to nose.

At about this time too, the ‘flaneur’ emerged in France, a ‘scientist of the sidewalk, a detached observer, dissecting the metropolitan crowd.’ To quote Baudelaire: “The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and profession are to become one flesh with the crowd.” Walking in cities was at last becoming fashionable, at least for some.

Virginia Woolf was a great advocate of city walking too. Her character Mrs Dalloway remarks: ‘I love walking in London. Really, it’s better than walking in the country.’ And in Street Haunting: A London Adventure, she writes:

“Into each of these lives (the other street walkers) one could penetrate a little way, far enough to give oneself the illusion that one is not tethered to a single mind, but can put on briefly for a few minutes the bodies and minds of others. One could become a washerwoman, a publican, a street singer. And what greater delight and wonder can there be than to leave the straight lines of personality and deviate into those footpaths that lead beneath the brambles and thick trees trunks into the heart of the forest where lives those wild beasts, our fellow men?”

Whereas the romantics tended to use nature as a means of looking into their own soul in solitude – a sort of ‘reflective intro-spection’, these urban explorers were the reverse – they used their journeys to look out at the masses – a sort of ‘extra-spection’.

‘The town a part of the country and the country a part of the town’

Toward the end of the nineteenth century visionaries were starting to think about how better, altogether more pleasant cities could be created.

William Morris, in ‘News from Nowhere’ (1890), a utopian vision, has his observer wake, and finds himself in the London of the twenty-first century. This is what he imagines:

“The soap-works with their smoke-vomiting chimneys were gone; the engineer’s works gone; the leadworks gone; and no sound of riveting and hammering came down the west wind… I opened my eyes to the sunlight again and looked round me, and cried out among the whispering trees and odorous blossoms, ‘Trafalgar Square’.”

Morris once described his goal as making ‘the town a part of the country and the country a part of the town’. The aim was not one of uniformity, but rather of weakening the starkness of the contrast. This was to be achieved by introducing the best features of each into the other. ‘I want the town to be impregnated with the beauty of the country,’ Morris insisted, ‘and the country with the intelligence and vivid life of the town.’

Ebenezer Howard, the founder of the Garden City Movement, was greatly influenced by these thoughts, in his idealistic vision of a decentralised urban future. ‘Town and country must be married,’ he wrote in his landmark treatise ‘Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1902), and ‘out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilization.’

Howard’s prescription was a pattern of small, well-defined towns, with their own industries, shops, cultural facilities and generous public open space, each as nearly as possible self-sufficient. Because their size would be limited and finite through strict planning control, all parts of these towns would always be within each reach of the countryside. Letchworth Garden City was his creation and was also the forerunner of the New Town Movement.

The challenge of the war years and recession

But the divide between town and country persisted, and perhaps grew even stronger in the inter-war years as aspirations grew and people became more frustrated by the political order. The political emphasis in this period was on housing (the Housing Act of 1919 pledged 500,000 houses – ‘homes fit for heroes’ – within three years), and inevitably this was also the period of the rapid growth of the suburb as people strove to escape the confines of city squalor and start a new life with more space and amenities. The ‘right to buy’ scheme kicked in during this period and the exodus from the centre of towns to the suburbs gathered pace, fuelled by attractive deals and the emergence of large building firms that created ‘ready to live in’ properties with all mod cons.

In the 1920s, TS Eliot writes in ‘The Wasteland’ of a city that is somehow still disconnected and passionless:

“Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.”

The persistence of this continuing divide between the ‘lifeless’ city and the ‘bountiful’ countryside was epitomised in the writing of GM Trevelyan, historian and founder of the YHA. In 1936, he wrote, in an introduction to ‘Walking Tours and Hostels in England’:

“Mankind, particularly in our island, has been locked up in the great cities away from nature and from its health & beauty. Our race, almost more than any other, is denied the natural use of its limbs which machinery displaces, is denied the enjoyment of the old human instincts, the delight in sunset and sunrise, noontide and dew, woodland, field and running stream, valleys, woods and hills.

For hundred of thousands of years, mankind was bred on the lap of Nature. It is only in this last century that he has suddenly been seized upon and locked away from his mother earth, locked away from God’s country in man’s ugly artificial towns, where he sees nothing of Nature but a thin strip of sky between the chimney pots. It is not, and it cannot come to good.”

Planing, more planning and the monster car…

The immediate post-war years, 1945-50, were a time of immense social change and of course the emergence of the welfare state. As well as the growing provision for health for everyone – the NHS was founded in 1947 – it was also a great time for the outdoors, with the Act of Parliament to establish National Parks passed in 1949.

The Green Belt, covering a dozen of our larger cities, emerged out of this furnace of social revolution and remains intact (although under much pressure) to this day. There was a strong desire to avoid further urban sprawl, along the lines that was being witnessed in American cities; and to that end the Town & Country Planning Act was passed in 1947, allowing local authorities to include green belt proposals in their development plans. As Ian Nairn, architectural campaigning journalist, memorably remarked: “When the green belt came into force, the outward swell of building stopped dead, two fields away…there is a terrifying forty miles of solid brickwork behind those demure-looking semis half a mile away. You feel as Canute might have on the beach, but unexpectedly successful.” (1966).

And The Clean Air Act of 1956 made cities more pleasant places to walk through. An Act of Parliament was passed in response to London’s Great Smog of 1952, with fog so thick it killed more than 10,000 people and even stopped trains, cars and public events. The government introduced a number of measures to reduce air pollution, especially by introducing ‘smoke control areas’ in which only smokeless fuels could be burnt. This Act helped to fundamentally improve the air quality in cities and the desirability of walking around.

But, on the other hand, the need for rapid homebuilding to replace the war damage, the growth in traffic and its associated safety risks, and a planning doctrine, embodied in Colin Buchanan’s 1963 ‘Traffic in Towns’, which manifested the view that motorists and pedestrians should be separated completely through the use of flyovers, clearways and gyratory systems, led to dramatically reducing the pleasure and ease of walking through cities.

Buchanan expressed it starkly: “It is impossible to spend any time on the study of the future of traffic in towns without at once being appalled by the magnitude of the emergency that is coming upon us. We are nourishing at immense cost a monster (the motor car) of great potential destructiveness, and yet we love him dearly. To refuse to accept the challenge it presents would be an act of defeatism.”

Perhaps the best (or worst) example of this was the motorway carved into the centre of Birmingham in the early 60s, destroying the shape of the town and cutting natural pedestrian routes.

The fight back begins

Ian Nairn began his famous fight back in The Outrage issue of the Architectural Review in 1956, in which he attacked post war planners’ destruction of Britain. But it was not until the 1980s that cities began to emerge from these dead-end policies that so blighted the centre of cities, making them most unwelcoming places to walk through.

The defining work of literature that changed perceptions of city vs. country was Richard Mabey’s ‘The Unofficial Countryside’, published in 1973. In it he writes:

“Our attitude to nature is a strangely contradictory blend of romanticism and gloom. We imagine it to ‘belong’ in those watercolour landscapes where most of us would also like to live. If we are looking for wildlife we turn automatically towards the official countryside, towards the great set-pieces of forests and moor. If the truth be told, the needs of the natural world are more prosaic than this. A crack in the pavement is all a plant needs to put down roots. An old-fashioned lamp-standard makes as good a nesting box for a tit as any hollow oak. Provided it is not actually contaminated there is scarcely a nook or cranny anywhere which does not provide the right living conditions for some plant or creature.”

And his startling assertion: “It is easy to become sceptical of the ecological soothsayers when you learn, for instance, that there are twice as many birds per acre in urban areas as there are in most of the countryside.”

Mabey’s book made me realise that nature doesn’t make the distinction between city and country in the way that humans do, particularly humans with a built-in prejudice in favour of a ‘pastoral idyll’ – nature is simply looking for a way of surviving and reproducing, and it is endlessly flexible.

City walking becomes cool…

Following on from the ‘Unofficial Countryside’ came a whole new genre of writing about walking through cities on foot; most notably Ian Sinclair’s ‘Lights out for the Territory’ (1997) and his walk around the M25 ‘London Orbital’ (2002). This genre of writing is often labelled ‘psychogeography’, a way of exploring cities designed to jolt the walker into a new awareness of the urban landscape and popularised by Will Self in his newspaper column of the same name in the Independent. He famously walked to his publishers in the centre of New York on foot from his home in South London (admittedly via the airport).

Other recent notable books in this genre include ‘Walk the Lines: The London Underground Overground’ and the brilliant ‘Edgelands: Journeys into England’s True Wildernesses’ which includes this acute observation of that strange no-man’s land between town and country: “There are no signposts leading to the Edgelands, no motorway signs with speed-legible Transport font and pre-ordained background colour pointing us towards their fastnesses. Edgelands aren’t sites. They don’t behave like castles or bird reserves or historic market towns. Nobody asks, ‘are we there yet?’

But also the ‘mainstream’ appreciation of walking in cities was becoming just as important. The Green London Way, formed in 1991, is a different way of looking at London: a walking route of over 110 miles encircling the capital, the first long-distance footpath around London and one of the very first entirely urban long-distance footpaths in the country.

In the words of Bob Gilbert, creator of the route: “What was once regarded as a rather cranky idea has now been enthusiastically embraced – including by some of those who rejected it at the time – and it even has its own celebrity adherents. This acceptance of the value of urban walking in its own right, and not just a poor relation of a ‘real’ rural walk, can only be welcomed. It marks a change in attitude, an acceptance of a different sort of landscape, and a realisation of the richness that an urban exploration has to offer.”

But perhaps the most significant factor during this period was the switch in employment from manual to office work. Manufacturing collapsed in cities between the 70s and the 90s, which had two beneficial side-effects – the greater focus that became possible on the environment, and the regeneration of large open spaces that had previously been industrialised. William Morris’ vision becoming reality in the twenty-first century, just as he had foreseen!

Urban regeneration became a matter of political priority, and several initiatives were launched – Urban Regeneration Corporations, Enterprise Zones, City Action teams and Task Forces and City Challenges.

Combined with a new vision of the importance of the aesthetics of a city and their walker-friendly appeal, a revolution in city planning finally took place.

One by one councils and local authorities have changed from seeing open spaces as a problem (litter, vandalism, noise, lewd behaviour) to an opportunity (healthiness, attractive landscape, leisure lifestyle).

The view of English Nature, expressed in their document Accessible and Natural Green Space in Towns and Cities, English Nature, 1995, now represents a common consensus: “Accessible, natural places provide the qualities of adventure and restoration which contribute much to people’s health and well-being, and thereby contribute most to sustainable communities.”

This was echoed in The Heritage Lottery Report 2014, The State of UK Public Parks: “Parks are vital community assets, essential to the local economy, to public health and well-being, to tourism, to social cohesion and to nature.”

The green and walkable city emerges

UK cities are now going through a truly transformative phase, making them much more appealing places to walk through than they used to be.

As a result, neither London nor almost any of the other great cities of the UK looks anything like it did a generation ago in terms of visual and walker appeal. Take the South Bank in London, for example: it was a bleak zone that you passed through as quickly as possible to get to the National Theatre or to Waterloo Station; now it is teeming with life and walkers 24/7. Battersea Power Station, that symbol of air pollution from the 1950s, is soon going to incorporate luxury apartments with ‘gardens in the sky’ and fabulous views. The docklands area in Liverpool is now full of visitors and night time activity.

Almost all UK cities are finally casting off the shackles of the motor car and establishing shared outdoor living spaces that bring the city to life and create a buzz of well-being and creativity.

National bodies have played an important role in this transition:

- The National Lottery has spent £652 M on restoring parks and green spaces in cities; this has been matched by time and money from councils and community groups, collectively delivering a renaissance in the fortune of many parks.

- The National Trust has recently announced a new strategy that focuses less on historic country houses and more on urban green spaces

- National Parks are beginning to re-think what might constitute a national park. Why not make London a National Park City, for example– after all is has the largest urban forest in the world, with more than 8 million trees; and 3,000 parks and 30,000 allotments. Why drive hundred of miles and deposit a carbon footprint when you could enjoy nature outside your own front door?

This shift in thinking has been underpinned by popular movements around the world reclaiming our cities:

- The ‘Ciclovia’ – – car-free days in major cities, where the people reclaim the streets (Paris had one a few months ago and the Champs–Élysées was thronged with thrilled pedestrians)

- Urban spaces re-purposed for leisure e.g. urban beaches, concert venues

- Spaces increasingly used as ‘open-air’ living rooms – where people stop and relax, interact, engage with their surroundings

- Art installations along the route – fountains, water features, sculpture trails

- Ambitious extension of car free zones: Oslo, for example has declared its ambition to be car-free in the city centre by 2019

- The creation of new ‘green spaces’ which become huge tourist attractions e.g. the Hi-Line in New York, the South Bank in London; and perhaps soon the garden bridge over the Thames.

And the health benefits have become much more valued:

- Recognition that green spaces (in sizes S,M, L and XL)) are a crucial part of a healthy human habitat, in an age of obesity and increased mental stress issues

- A growing appreciation of the calming and restorative powers of nature, especially trees, amidst a bustling city – ‘biophilia’

- There is even an app now at www.walkonomics.com , which helps you find the most tree-filled route around a city

Most importantly, city planning attitudes have fundamentally changed:

- A key thrust of city planning nowadays is to re-connect cities: Linking Lincoln, Connecting Leicester etc.

- The post-war consensus, that traffic was the biggest challenge that a city faced and that it should be given priority over pedestrians, has been broken

- The ‘woonerf’ or shared space concept is taking hold, whereby pedestrians, cyclists and cars use the streets on a shared basis

- ‘Smarter’ public transport is helping the cause – passes, alerts, on-call, free wi-fi, public bikes etc.- making public transport more appealing

- In parallel, more restrictions are being placed on cars – congestion charges, lower speed limits, car-free zones – making cars a less attractive proposition

- Policies to encourage the re-habitation of city centres in favour of the suburbs are creating locals who care about their environment

- And the councils are actively encouraging much more street life, by promoting festivals, street fairs, pop-up art installations etc.

The next generation will look back and wonder how we ever allowed our cities to be clogged by cars and strangled by ring roads to the extent that we all fled to the suburbs or countryside. The first half of the twenty first century will be the era when cities are recreated as they were in the days of the first Greek and Roman cities – public spaces for citizens to share and enjoy. This will have been immensely facilitated by the ‘Google car’, which will optimise road transport, dramatically reduce the volume of traffic and blur the line between public and private transport.

The Romans were right. The best city is the one infused by countryside – the ‘rus in urbe’! We will know that we have won when London, Sheffield and Edinburgh (just to get things going) have been declared as urban parks!

Leave a Reply