All waterways lead to the London Docks

This second stage of the walk takes us through the heart of what were the London Docks, now largely re-developed as a residential and leisure haven.

WALK DATA

- Distance: 9.3 km (5.8 miles) – the extra loop will add 1.5kms (0.9 miles) to this

- Typical time: 2 ¾ hours (extra 20 mins for loop)

- Height change: 10 metres

- Start: Timber Lodge Café (E20 1DY) or Monier Rd Bridge (E3 2ND)

- End of this stage: Tower of London (EC3N 4AB)

- Finish if stopping here: Tower Hill Underground Station (EC3N 4DJ)

- Terrain: Straightforward; sturdy footwear recommended

BEST FOR

‘Green Spaces’

| Parks, gardens, squares, cemeteries | Olympic Park, King Edward Memorial Park, Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden |

| Rivers, canals, lakes | River Lea, Lee Navigation Channel, Limehouse Cut, Limehouse Basin, River Thames, Shadwell Basin, The Ornamental Canal, St Katherine’s Dock |

| Stunning cityscape | River Thames entrance to Limehouse Basin, Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden |

‘Architectural Inspiration’

| Ancient Buildings & Structures (pre-1714) | Tower of London (originated in 1066) |

| Georgian (1714-1836) | St Anne’s Limehouse (1727) |

| Victorian & Edwardian (1837-1918) | Abbey Mills Pumping Station (1868), Tower Bridge (1894) |

| Industrial Heritage | Greenway (1860s), the Three Mills, Spratt’s Works (1860), Ropemakers’ Fields, Accumulator Tower (1852), London Docks (1850s) |

| Modern (post-1918) | Aquatics Centre (2011), The Mission (1924) |

‘Fun stuff’

| Great ‘Pit Stops’ | View Tube, The Grapes, White Mulberry |

| Quirky Shopping | St Katherine’s Docks |

| Places to visit | Aquatics Centre (public swimming), Tower of London, Tower Bridge |

| Popular annual festivals & events | Limehouse Festival (July), Shadwell Basin Paddle-Fest (Sep), St Katherine’s Dock Classic Boat Festival (Sep) |

City population: 8,538,689 (2011 census)

Urban population: 9,787,426 (2011 census)

Ranking: Largest city in UK

Date of origin: 43AD

‘Type’ of city: capital city; seat of government, commerce and culture.

City status: Since time immemorial

Some famous inhabitants of the areas around this walk:

Limehouse: Charles Dickens’ godfather, Christopher Huffam, ran his sail making from Newell Street. Huffam is said to be the inspiration for the Paul Dombey character in Dickens’ Dombey and Son. Contemporary residents include Sir Ian McKellen (actor), Matthew Parris (journalist), Steven Berkoff (actor) and Lord David Owen (politician).

Jerome K Jerome (Lindfield St, Poplar), Frances Bacon (Narrow St, Limehouse), Sir David Lean (Narrow St, Limehouse); Captain James Cook (1728–1779).

St Katherine’s Docks: Ruth Kelly (politician), David Mellor (former politician and broadcaster), David Suchet (actor).

The New River in London, bet you don’t know where it is. Find out more by walking along it, you will be amazed:http://urbanrambles.org/walks/uk/england/london/london-other/north-london-stage-2-the-new-river-from-alexandra-palace-to-islington-3954

The New River in London, bet you don’t know where it is. Find out more by walking along it, you will be amazed:http://urbanrambles.org/walks/uk/england/london/london-other/north-london-stage-2-the-new-river-from-alexandra-palace-to-islington-3954

Notable architects/planners: The London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) was a quango agency set up by the UK Government in 1981 to regenerate the depressed Docklands. Although initially fiercely resisted by local councils and residents, today it is generally regarded as having been a success and is now used as an exemplar of large-scale regeneration

Number of listed buildings: Tower Hamlets: 943, of which 21 are Grade I and 38 are Grade II*

Films/TV series shot here:

River Lea: An old foundry next to the “Big Breakfast” house was used as the main movie location for Anthony Minghella’s film Breaking and Entering, starring Jude Law and Juliette Binoche.

‘The Sweeney’ (1975-78) was made in the abandoned wharves and warehouses of the old London Docks. The new Docklands was the setting of the BBC’s science fiction series ‘Bugs’.

St Katherine’s Docks: The Long Good Friday (1980)

Tower Bridge is one of the great iconic landmarks of Britain and has been used in hundreds of films and TV series (although in recent years it seems to have been partially eclipsed by the Millennium Bridge). Notable films include: An American Werewolf in London (1981); James Bond’s The World Is Not Enough (1999); Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Sherlock Holmes (2009)

CONTEXT

The River Lea has been a vital artery for Londoners for the last two millennia, provisioning the city with fresh water and having the mantle of a ‘service shaft’ to the city forced upon it, looking after its sewage, solid waste, electricity & gas and general provisioning needs.

It is very much ‘boundary’ territory, a no man’s land between boroughs (it’s the dividing line between Tower Hamlets and Newham), the ‘ugly sister’ of the Thames that is seldom seen; relegated to a purely functional service role but, with the massive impetus of the Olympic re-generation, now being re-discovered as a natural green space with unlimited potential as a place to live and flourish.

Almost the whole of our walk is alongside water – part natural, part created, all used to provision London and to help make London the greatest trading nation on earth in the 19th century.

And, after several stutters and delays, that industrial heritage is being transformed in front of our eyes as a haven of waterfront apartments, green spaces and leisure activities; starting in the early 80s closest to the city at St Katherine’s Docks, then the Limehouse Basin, then the London Docks, moving steadily outwards with a major shot in the arm from the Olympic regeneration. As you walk south from The Olympic Park near the start of the walk, you feel at times as if you are in the midst of a new city emerging from the rubble of a wasteland. More than almost any other urban ramble, this makes you think about the huge potential to re-develop brown field sites.

THE WALK

So we set out on the second leg of our journey from the Timber Lodge Café; or if you are starting here, from Stratford International, which has good access by the LDR and Overground trains.

It’s at this point that you really start to appreciate what a magnificent ‘green push’ has been made of the park. Let me blow your mind with a few statistics:

- 4,000 semi-mature trees have been planted

- More than 10 football fields’ worth of nectar-rich annual and perennial meadows have been created

- Wetland bowls and rare wet woodlands in the north of the Park (we’re just about to walk past them in fact) create habitats and help manage floodwater

- 300,000-plus wetland plants have been planted as part of the UK’s largest ever urban river and wetland planting, comprising over 30 species of native reeds, rushes, grasses, sedges, wet wildflowers and irises.

There are many routes through this splendid park, take your pick; we elected to go through the Wetland Walk and then back over the Eastcross Bridge over the river and then approach the main stadium from Mandeville Place.

The Olympic Stadium stands as a proud reminder of the halcyon summer of 2012; is now West Ham Football Club’s home. They took up residence for the 2016-17 season. Other football clubs are very jealous of the incredibly good deal they appear to have struck, but the fans are not so sure, it doesn’t have the intimacy of their old ground.

We stayed along the river, walking to the right (west) of the stadium and soon arrived at the Old Ford Lock. This marks the end of the Hackney Cut – a channel built in the 18th century to cut off a large loop in the river. In the 1990s, the neighbouring old lock-keeper’s three cottages were used for television filming of The Big Breakfast, Channel 4’s early morning show.

Old Ford Island is just to the south of the Greenway (of which more in a moment) – it’s now a nature reserve, consisting of grassland, tall herbaceous vegetation and scrub, surrounded by trees. Although it is not accessible to the public, it can be viewed over the gate from the Greenway.

Loop via Abbey Mills Pumping station

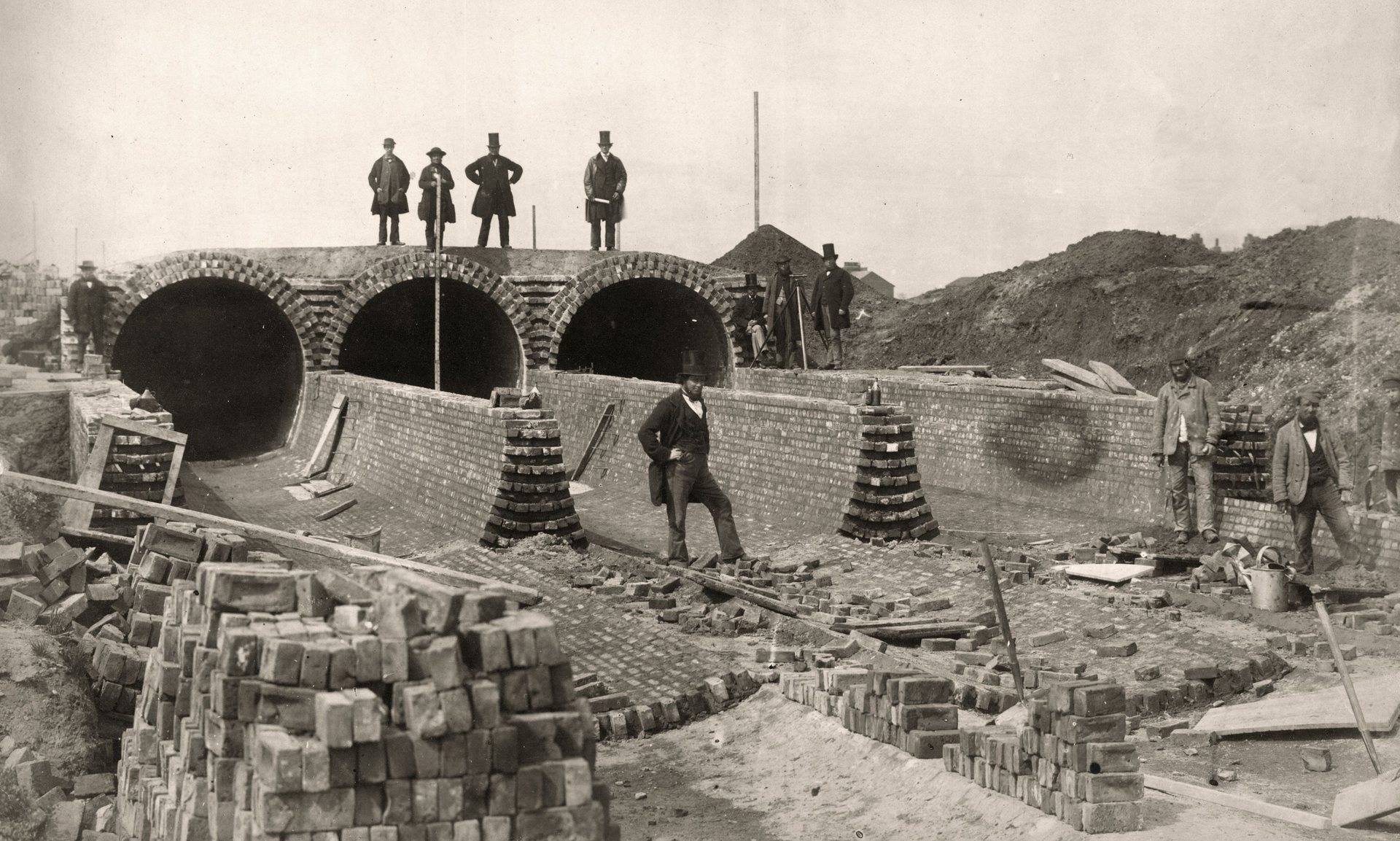

Bazalgette building his sewer

The Greenway is a footpath and cycleway atop an embankment which continues as far as the eye can see. It would be easy to imagine that this must have been some Anglo-Saxon defensive wall, like Offa’s Dyke or Devil’s Dyke, protecting the good folk of London from the wild men of Essex; but the truth turns out to be more prosaic. Its acronym is NOSE, longhand The Northern Outfall Sewage Embankment, a key component of Victorian engineer’s Sir Joseph William Bazalgette’s famous London sewers, instigated after an outbreak of cholera in 1853 and the ‘Great Stink’ of 1858. It runs from Wick Lane in Hackney to Beckton sewage treatment works south of Barking by the River Thames. One of the greatest nuisances for an urban rambler is stepping on shit, but here there’s no way of avoiding it. Below your feet are four 9-inch pipes containing the biggest sewage flow in Britain at over 100 million gallons per day.

View Tube, a viewing platform on the Greenway, with its eatery the Container Café, offers the best views of the Olympic Park. You can’t miss it. It’s lime green and made from recycled shipping containers! The Trip Advisor brigade seem to like it more than the Timber Lodge Café: “We ate here on our day out to the Olympic Park. Very quirky space. Our lunch was delicious and good value for money. The Ukelele group were practising for their show tomorrow. You can have a go on the piano… write a story on the wall, draw a picture and generally hang out.”

At this point we had to clamber down off the Greenway along Marshgate Lane, left after the bridge over the Bow Back river, right along Blaker St, turn left at Stratford High St and then re-join the Greenway heading SE after crossing Three Mills Wall River (the actual Greenway from the View Tube to Stratford High St looks as if it will be a long while before it’s restored, if ever).

Now, what’s this coming up on our right? It looks like a town hall that has lost its town, a piece of Venetian Gothic splendour which has popped out of nowhere. It turns out to be the Grade II listed Abbey Mills Pumping Station, a part of Bazalgette’s grand scheme, aptly described as a ‘cathedral of sewage’. Two Moorish-styled chimneys – unused since steam power had been replaced by electric motors in 1933 – were demolished in 1941, as it was feared that a bomb strike from German bombs might topple them on to the pumping station. Next to it, you will see its much more functional replacement.

The route then took us through another green space of the Lea Valley Park onto Three Mills Green, which has a large play space and a good sense of scale.

End of loop

The Three Mills are former working tidal mills and reputed to be amongst the most powerful tidal mills in the world.

Stratford Langthorne Abbey, founded in 1135, acquired the three mills some time in the 12th or 13th centuries, and the area became known as Three Mills. By the time Henry VIII dissolved the abbey in the 1530s, the mills were grinding flour for the bakers of Stratford-atte-Bow, who were celebrated for the quality of their bread and supplied the huge City of London market. In the 17th century, the mills were used to grind grain, which was then used to distil alcohol; they became a major supplier to the alcohol trade and gin palaces of London. Distilling ceased in 1941 during the rationing shortages of The Second World War.

Part of the site became a film production studio in the 1980s, called 3 Mills Studios. The site is now one of London’s most important film and TV studios. Many feature films have been made here, including; Fantastic Mr Fox, Made in Dagenham, Never Let Me Go and Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels.

Navigating from the River Lea to the River Thames using nature’s intended route necessitates traversing Bow Creek, a winding tidal waterway not best suited to inland vessels. Consequently, The River Lea Act 1766 authorised the construction of the Limehouse Cut, a straight section linking the River Lea at Bromley-by-Bow to the Thames at Limehouse, saving considerable time and trouble. It is London’s oldest canal.

Soon after we had left the Lea heading east along the Limehouse Cut, we came across Spratt’s Works on the left bank. A century ago this was the largest dog food factory in the world. James Spratt set up his business in 1860 and soon his PR outfit declared the business to be ‘a howling success’. Barges would deliver fish heads for processing into pet food. After the business closed in 1969 (gone to the dogs?!), the warehouses were left derelict for some years until they were redeveloped in the late 1980s.

Further up on our right we spotted a massive cathedral-like building, standing back about two hundred metres from the canal. A real mishmash of architectural styles (art deco, perpendicular Gothic, neo-Georgian, art nouveau) but nonetheless impactful and imposing, The Mission was built in 1924 as a hostel for sailors who’d arrived in the nearby Limehouse Basin and needed a bed.

Back at the start of the 1960s, the building had caught the eye of the Situationists Movement, who held one of their annual conferences there. They were essentially an artistic group with left wing political beliefs who were interested in, amongst other things, unitary urbanism and psychogeography. Now in the (unlikely) event that you have forgotten your unitary urbanism definition, this is Wiki’s attempt: “In the relative utopia of the UU ideal, the structural and artistic elements of human’s metropolitan surroundings are blended into such grey area that one cannot identify where function ends and play begins. The resulting society, while it caters to fundamental needs, does so in an atmosphere of continual exploration, leisure, and stimulating ambience.” I reckon that’s pretty much what we aim to do on our walks!

St Anne’s Limehouse is an attractive early 18th-century church designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, intended as one of twelve ‘Queen Anne’ churches built to serve the needs of the rapidly expanding population of the day. Queen Anne decreed that as the new church was close to the river it would be a convenient place for sea captains to register vital events taking place at sea. Therefore she gave the church the right to display the second most senior ensign of the Royal Navy, the White Ensign. The prominent tower with its golden ball on the flagpole

became a Trinity House ‘sea mark’ on navigational charts, and the Queen’s Regulations still permit St. Anne’s Limehouse to display the White Ensign at all times.

Ropemakers’ Fields was laid out under the auspices of London Docklands Development Corporation on derelict land, together with land above the new Limehouse Link Tunnel. Although a new park, it has considerable historical interest in that it was formerly the site of rope making in Limehouse; where rope for marine anchors, rigging and mining was made for many centuries. Samuel Pepys refers to a visit to the rope-yard in 1664. Limehouse became famous for the quality of rope it produced for nautical use. Sisal fibre was spun into rope between two rigid wooden frames. These frames, known as ropewalks, could be several hundred yards apart.

The Limehouse Basin, opened in 1820 by the Regent’s Canal Company, was formerly known as Regent’s Canal Dock and was used by seagoing vessels and lighters to offload cargoes to canal barges, for onward transport along the canal. By the mid 19th century the dock and canal were a huge commercial success due to their importance in the supply of coal to the numerous gas works and latterly electricity generating stations along the canal and for domestic and commercial use. At one point it was the principal entrance from the Thames to the entire national canal network.

To the east of the canal entrance, behind a viaduct arch, is the Accumulator Tower, built in 1852 to provide hydraulic power for cranes and winches in the basin. It was the first of its kind in the country. Sadly, it is only open on London Heritage Open Days; the view from the top alone definitely merits a trip!

The redevelopment of the Basin started in 1983 as part of the London Docklands Development Corporation’s overall master plan for the Docklands area. However, it took many years to come to fruition. The property boom and bust of the 1980s set back progress considerably, as did the construction of the Limehouse Link tunnel that was built under the north side of the basin in the early 1990s. By early 2004 the majority of the once derelict land surrounding the basin had been developed into luxury flats. I hate to say it, but the apartments around the basin itself often have a rather soulless feel about them; if you can conjure up the exact opposite of what a lively Italian piazza might feel like on an early summer’s evening, then that’s just about it… very different from how it must have been back in the day.

Charles Dickens’ godfather Christopher Huffam lived and ran his sail making and chandlery business from a substantial house in Newell St, just on the south side of the basin. Huffam adored his godson, declaring the boy a prodigy, tipping him half a crown on his birthday and encouraging him to dance and perform comic songs upon the kitchen table – and also, it is said, upon the bar at The Grapes. In the company of his godfather, Dickens first explored Shadwell and Limehouse, engendering a lasting fascination with these teeming waterside regions that he returned to throughout his writing life, both in fiction and journalism.

The Cruising Association’s headquarters overlooks the Marina, at the gateway between the tidal Thames and the inland waterways. Members can even arrive by boat. It is my sister’s ‘club’ when she and her husband are in London, offering good value at £60 or so a night and a porthole to look out of for those who are missing the sea.

View of Canary Wharf from Limehouse

As we headed west along the Thames Path, we soon reached the King Edward Memorial Park (3.3. hectares, 8.2 acres). The park includes a bandstand, waterfront benches, children’s play area, bowling green, all weather football pitch and tennis courts. It was opened in 1922 by King George V and Queen Mary with the following dedication: “In grateful memory of King Edward VII. This park is dedicated to the use and enjoyment of the people of East London for ever.” Still working as intended nearly a century later.

Shadwell Basin is the only significant body of water surviving today from the London Docks, which extended west from here but were in-filled in the 1970s as a prelude to redevelopment. It is now a maritime square of 2.8 hectares used for recreational purposes (including sailing, canoeing and fishing) and is surrounded on three sides by a waterside housing development (somewhat uninspiring in my view).

On the left of the basin as we walked along it we noticed the Wapping Hydraulic Power Station, which is now an arts and culture venue; and the day we went was exhibiting photos by Annie Liebovitch. It was built in 1890 to supply hydraulic power to many of London’s theatres, shops, docks and hotels via miles of subterranean pipes. The compressed energy was used to power lifts, stage curtains, cranes and even the bascules of London Bridge.

The London Docks occupied a total area of about 12 hectares (30 acres), consisting of Western and Eastern docks linked by the short Tobacco Dock. The Western Dock was connected to the Thames by Hermitage Basin to the south west and Wapping Basin to the south. The Eastern Dock connected to the Thames via the Shadwell Basin to the east. The principal designers were the architects and engineers Daniel Asher Alexander and John Rennie.

The docks specialised in high-value luxury commodities such as ivory, spices, coffee and cocoa as well as wine and wool, for which elegant warehouses and wine cellars were constructed. One drawback was that the system was never connected to the railway network.

As early as the start of the 20th century the docks were becoming outdated as steam power meant ships were built too large to fit into them. Cargoes were unloaded downriver and then ferried by barge to warehouses in Wapping. This system was uneconomic and inefficient and one of the main reasons that the docks in Wapping were the first to close in the late 1960s. After more than a decade of inaction, the area was finally redeveloped in the early 1980s and now comprises over 1,000 private properties.

We took the path from Shadwell Basin, through Wapping Woods (formerly the eastern Dock) and along the Ornamental Canal, which is a remnant of Tobacco Dock, the southern perimeter of the Western Dock; and finally Hermitage Basin.

Tobacco Dock is a Grade I listed warehouse, constructed in 1811 and used primarily as a store for imported tobacco. At its north entrance stands a 7 ft tall bronze sculpture of a boy standing in front of a tiger. In the late 1800s, wild animal trader Charles Jamrach owned the world’s largest exotic pet store, located on Ratcliffe Highway, near to Tobacco Dock. The statue commemorates an incident where a Bengal tiger escaped from Jamrach’s shop into the street and picked up and carried off a small boy, who had approached and tried to pet the animal having never seen such a big cat before. The boy escaped unhurt after Jamrach gave chase and prised open the animal’s jaw with his bare hands.

Rather more prosaically, it is now an events venue, with enough space to accommodate 10,000 people. We were a few days too early for the Gin Festival which was to be held there, which promised over 100 gins and a free Gin festival glass on admission – drinking and walking alongside a dock could have proved hazardous afterwards!

The Ornamental Canal is a pleasant diversion, more interesting in my view than taking the Thames Path at this point, which often is not along the waterfront. It was created from the ‘edge’ of the huge Western Dock and is, in contrast to the Limehouse Cut, probably London’s newest canal, although I suppose purists would argue that it’s not a canal at all. The wall on its south side is the original dock side and is full or interesting regalia – metal hooks, rings, depth marks and metal ladders recessed into the stonework.

The Hermitage entrance used to be the westernmost entrance to the London Docks but was too small to admit large modern ships and was closed in 1909. The Hermitage Riverside Memorial Gardens have a monument to those killed during the Blitz. The garden sits on the former site of Hermitage Wharf, which was destroyed by a firebomb in December 1940. There is also an interesting looking Dove sculpture by Wendy Taylor, which overlooks the park. It is just a pity the rest of the park isn’t as inspirational as the sculpture!

Even though Hermitage Riverside Memorial Garden is right on the banks of the River Thames, and is only a few minutes walk from the Tower Bridge and the Tower Of London, it is still most definitely a secret London garden. It may not be the prettiest garden in the world, but it is still a great place to escape the crowds and frenzy of central London.

St Katharine Docks took its name from the former hospital of St Katharine’s by the Tower, built in the 12th century, which stood on the site. An area of dense existing housing was earmarked for redevelopment by an Act of Parliament in 1825, with construction commencing in 1827. Some 1,250 houses were demolished, together with the medieval hospital of St. Katharine. Around 11,300 inhabitants, mostly port workers crammed into unsanitary slums, lost their homes; only the property owners received compensation. The scheme was designed by engineer Thomas Telford and was his only major project in London. To create as much quayside as possible, the docks were designed in the form of two linked basins (East and West), both accessed via an entrance lock from the Thames. Steam engines designed by James Watt and Matthew Boulton kept the water level in the basins about four feet above that of the tidal river.

Most of the original warehouses around the western basin were demolished and replaced by modern commercial buildings in the early 1970s, beginning with the bulky Tower Hotel. This was followed by the World Trade Centre Building and Commodity Quay. The development has often been cited as a model example of successful urban redevelopment, but the architecture doesn’t set the heart beating.

Tower Bridge. In the second half of the 19th century, increased commercial development in the East End of London led to a requirement for a new river crossing downstream of London Bridge. A traditional fixed bridge at street level could not be built because it would cut off access by sailing ships to the port facilities in the Pool of London, between London Bridge and the Tower of London.

A Special Bridge or Subway Committee was formed in 1877, chaired by Sir Albert Joseph Altman, to find a solution to the river crossing problem. It opened the design of the crossing to public competition. Over 50 designs were submitted, including one from civil engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette. The evaluation of the designs was surrounded by controversy, and it was not until 1884 that a design submitted by Sir Horace Jones, the City Architect (who was also one of the judges), was approved. Jones’ engineer, Sir John Wolfe Barry, devised the idea of a bascule bridge with two bridge towers built on piers. The central span was split into two equal bascules or leaves, which could be raised to allow river traffic to pass. The two side-spans were suspension bridges, with the suspension rods anchored both at the abutments and through rods contained within the bridge’s upper walkways.

The bascules are raised around 1,000 times a year. River traffic is now much reduced, but it still takes priority over road traffic. 24 hours’ notice is required before opening the bridge, and opening times are published in advance on the bridge’s website. When needing to be raised for the passage of a vessel the bascules are only raised to an angle sufficient for the vessel to safely pass under the bridge, except in the case of a vessel with the Monarch on board in which case they are raised fully no matter the size of the vessel.

Our final point was the Tower of London, steeped in history but almost always heaving with tourists; so you may just want to skirt by along the embankment, enjoying the architecture.

The Tower of London was founded in 1066 as part of the Norman Conquest. The White Tower, which gives the entire castle its name, was built by William the Conqueror in 1078 and was a resented symbol of oppression, inflicted upon London by the new ruling elite. The castle was used as a prison from 1100 (Ranulf Flambard) until 1952 (Kray twins), although that was not its primary purpose. A grand palace early in its history, it served as a royal residence. As a whole, the Tower is a complex of several buildings set within two concentric rings of defensive walls and a moat. There were several phases of expansion, mainly under King Richard the Lionheart, Henry III, and Edward I in the 12th and 13th centuries. The general layout established by the late 13th century remains despite later activity on the site.

And this is where the second leg of the walk finishes. Wow, how amazing has that been? If you are stopping here, walk up to Tower Hill tube; if you are continuing on to Stage 3, then stay on the Thames Path.

THE ROUTE

- Head S from the Timber Lodge Café and then W, with the wetlands to your left, crossing the River Lea over the Eastcross Bridge

- Then head S towards the Olympic Stadium, heading right at Mandeville Place to reach the River Lee Navigation Channel

- Join the path alongside the Lee Navigation Channel and head south, soon crossing the River Lea after Old Ford Lock

- When you reach signs to the Greenway (after approx. 500 metres), you have a choice; take the some steps along The Greenway; or stick to the main route, following the River Lea Way Greenway alternative route 4.1 Head east along The Greenway until you are close to the View Tube; at this point the path descends into Marshgate Lane, turn left along a footpath after the bridge over the Bow Back river, right along Blaker St, then left at Stratford High St and rejoin the Greenway heading SE after crossing Three Mills Wall River 4.2 Turn right just after the Abbey Mills Pumping Station and just before Abbey Creek; follow this path, cut back up a channel to cross bridge and come out on Three Mills Green 4.3 Go across Three Mills Green, past the production studios and re-join the main route

- There is a somewhat complex pathway interchange as you approach the A11, whereby you cross the River Lea, then turn immediately left along a walkway on the other side and cut down under the main road; the path then resumes on the west bank

- On reaching Three Mills take the bridge across the river and then turn immediately right; the path then continues along a spur between the River Lea and the Channelsea River

- When you reach the end of this spur, take the curving footbridge that takes you over the River Lea to join the Limehouse Cut, which you then join on the southern sid

- Follow the Limehouse Cut all the way to the Limehouse Basin, with the Ropemakers’ Field on your left, then skirt round on its southern side until just before you reach the Cruising Association building

- At this point head S alongside a small channel to the River Thames, turning right when you reach Narrow St, then very shortly left down some steps through a gate to the waterfront

- Turn right, right again, then left (W) along Narrow St; at the end of this street, the Thames Path goes along the waterfront again, through the King Edward VII Memorial Park until it reaches Wapping Wall

- Turn left (S) here and then immediately right (W) after the swing bridge along the southern side of the Shadwell Basin

- Cross the exit channel at the other end, then bear due W again through Wapping Woods, bearing slightly to the left to join up with the N side of the Ornamental Canal

- Follow this all the way to the east end of Wapping High St close to St Katherine’s Way, veering left, then right, then left again

- At Wapping High St turn right, then shortly left into St Katherine’s Way and head to St Katherine’s Docks

- Turn right into Mews St, then immediately left along a path by Marble Quay, across water, past the (recommended) White Mulberries café, over a bridge, past Starbucks and back to St Katherine’s Way

- Return to the waterfront, then head N before the main road, then head L through the tunnel to the Tower of London; the end of this stage is at Lower Thames St on the W side of The Tower.

PIT STOPS

The View Tube, The Greenway, Marshgate Lane, London E15 2PJ (07530 274160, www.theviewtube.co.uk) Coffee shop with views of Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, plus community arts venue and bike hire.

The Grapes, 76 Narrow St, London E14 8BP (020 7987 4396, www.thegrapes.co.uk) There has been a pub on this site since 1583. It features in ‘Charles Dicken’s Our Mutual Friend: ‘A tavern of dropsical appearance…long settled down into a state of hale infirmity.’

The Narrow, 44 Narrow St, London, E14 8DP (020 7592 7950, www.gordonramsayrestaurants.com/the-narrow) A Gordon Ramsay gastropub with superb views of the Thames.

Prospect of Whitby, 57 Wapping Wall, London E1W 3SH (020 7481 1095) The food is nothing special, but the setting, history and beer are. Try and get a seat overlooking the Thames, or in the summer the balcony. Henry VIII used to drink and eat here, whether he ate the fish and chips as we did is not recorded.

White Mulberries, D3 Ivory House, St Katharine Docks E1W 1AT (www.whitemulberries.com) An independent café in the middle of St Katherine’s Dock, with great cakes.

QUIRKY SHOPPING

A few interesting shops in St Katherine’s Docks, including a couple of galleries: The Alexander Miles Gallery and Artopia.

PLACES TO VISIT

Tower of London (www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london) If you absolutely, positively need to see the Crown Jewels (we’ve all probably done it once in our lives, or twice if you count taking the foreign exchange student…)

Tower Bridge (www.towerbridge.org.uk) Really merits a visit if you’re interested in finding out more about how the bridge was built. You can explore its structure, enjoy spectacular views and experience the glass floor, exhibitions and magnificent Victorian Engine Rooms! It gets a very good Trip Advisor rating, rated #11 of 1,381 things to do in London.

Leave a Reply